by Kaye Dee

Commentators are already referring to 1968 as the most turbulent year of the 1960s. We’ve seen civil unrest and sectarian violence; uprisings and brutal repression; new wars and intensification of old ones; political turmoil and assassinations; drought, famine and natural disasters, just to note some of the tragedies and strife dominating the headlines.

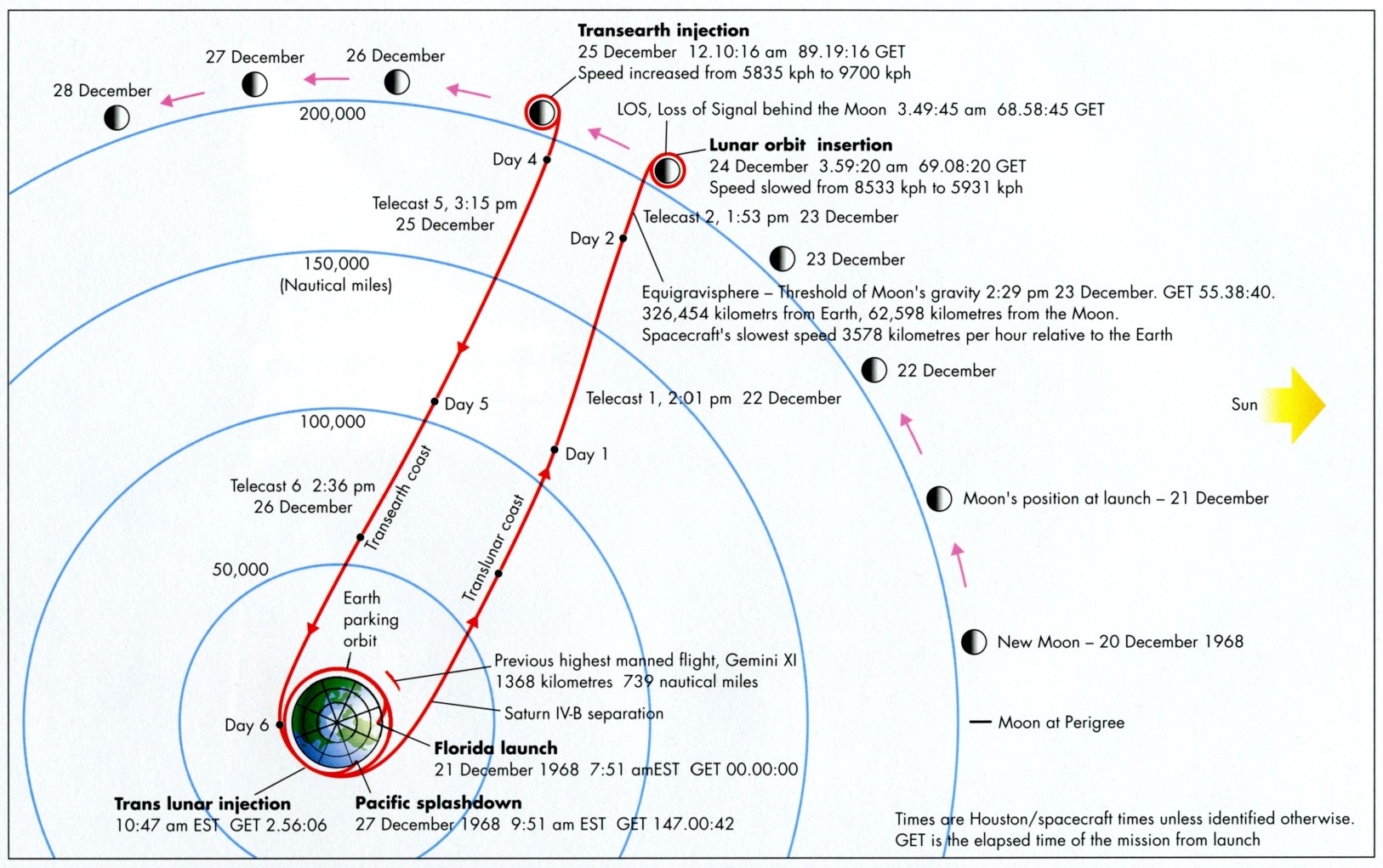

Yet this “worst of times” has still ended on a high note, thanks to NASA’s Christmas gift to the world – the Apollo-8 mission to the Moon.

As I write, the first daring spaceflight to the Earth’s nearest neighbour was completed only a few hours ago, splashing down in the early hours of the morning here in Australia. I’m tired but elated at the successful conclusion of the mission and the safe return of the crew. This historic mission has taken another crucial step in turning the ancient dream of reaching for the stars into reality, vindicating the inspiration that readers of the Journey draw from science fiction.

Taking the World on the Journey

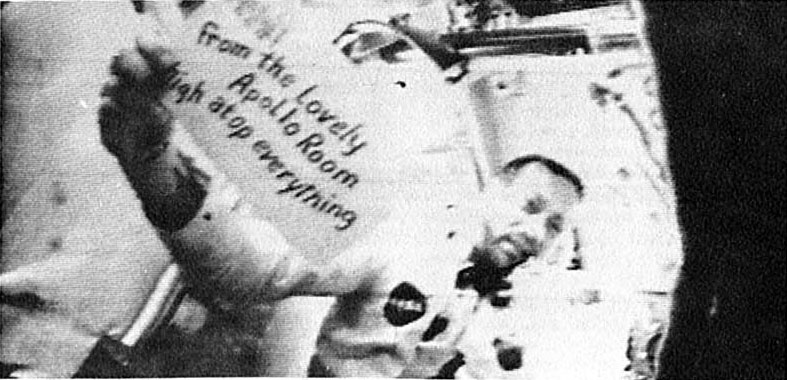

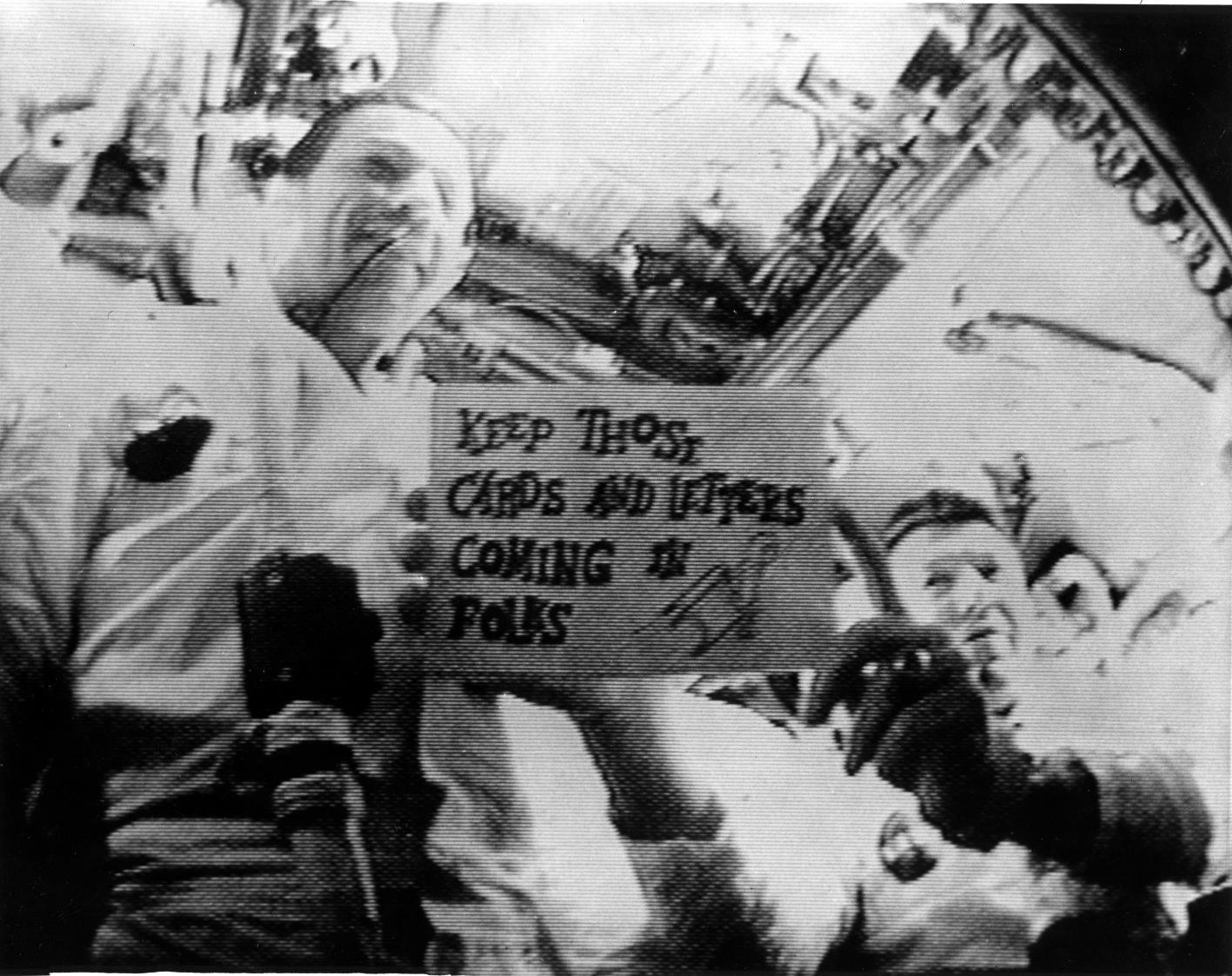

Thanks to the growing number of communications satellites now linking the world, almost three quarters of humanity has been able to participate vicariously in Mankind’s greatest space adventure to date. Apollo-8’s voyage has been vividly described to us through pictures, voice and the printed word by the world's journalists, and live from space by the astronauts themselves in their broadcasts during the mission.

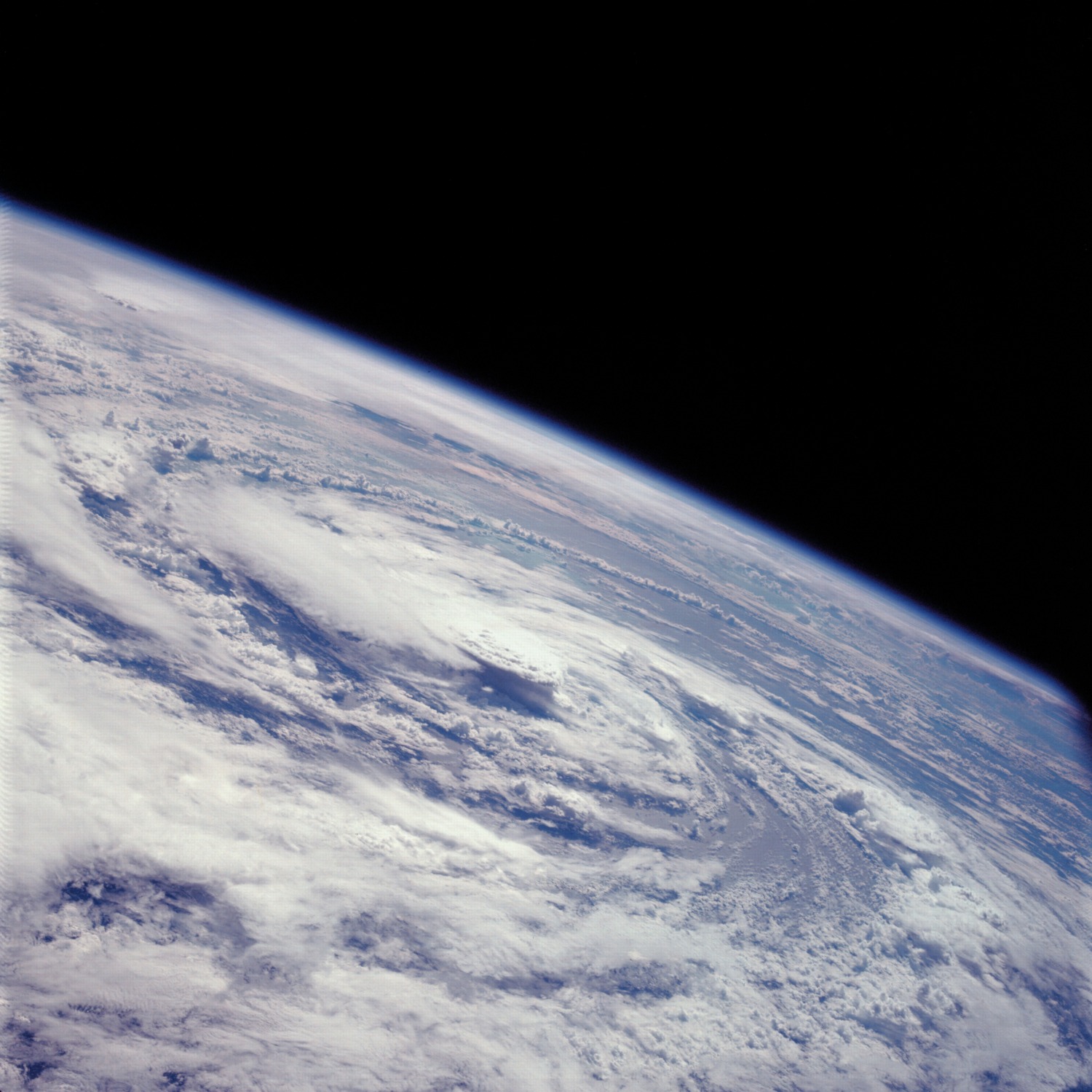

The Earth seen through a window of the Apollo-8 Command Module during the second television broadcast en route to the Moon. I can't wait to see the much higher resolution, full colour pictures!

The Earth seen through a window of the Apollo-8 Command Module during the second television broadcast en route to the Moon. I can't wait to see the much higher resolution, full colour pictures!

While we here in Australia may have missed out on some of the live broadcasts from space for technical reasons, people in Europe, the Americas, Asia and, it seems, even the nations of the Warsaw Pact have seen the view of the Earth from greater distances than ever before, live from the inside of the Apollo-8 Command Module. Around the world, spirits have been lifted and the public inspired by the courage of the Apollo-8 crew and the successful completion of their mission. I expect that, like me, many of you reading this will have been moved by the solemn reading from the Book of Genesis, a sacred text to three great religions, from lunar orbit on Christmas Day. It was a moment truly evoking “peace on earth and goodwill to men” – the spirit of Christmas – at the end of a fraught year for the world.

The Moon seen through a window of the Apollo-8 Command Module while the crew read the opening words of the Book of Genesis

The Moon seen through a window of the Apollo-8 Command Module while the crew read the opening words of the Book of Genesis

I think that the full impact of Apollo-8’s mission will take some time to emerge, especially once the photographs of the sights that the astronauts described to us during their flight become available to the public in the coming weeks. For this reason, I have decided to break my coverage of Apollo-8 into two parts. The first, today, will describe the background to the mission. Once NASA begins to process and release the photographs and films taken during the flight, the second part of my mission coverage will explore the lunar flight itself in more detail, illustrated by what I’m sure will be the magnificent images captured by the crew.

From Earth Orbit to Lunar Orbit

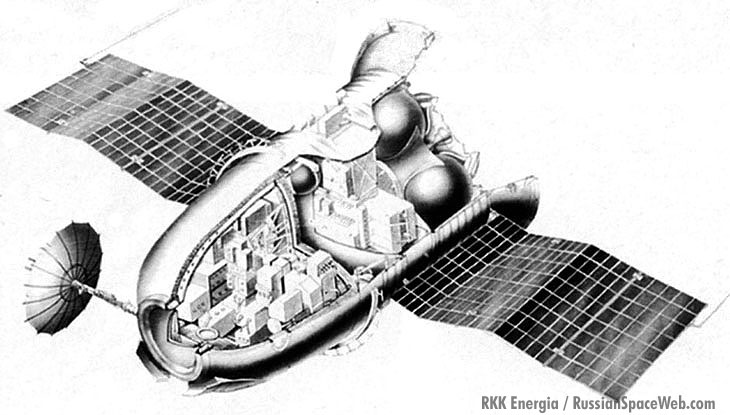

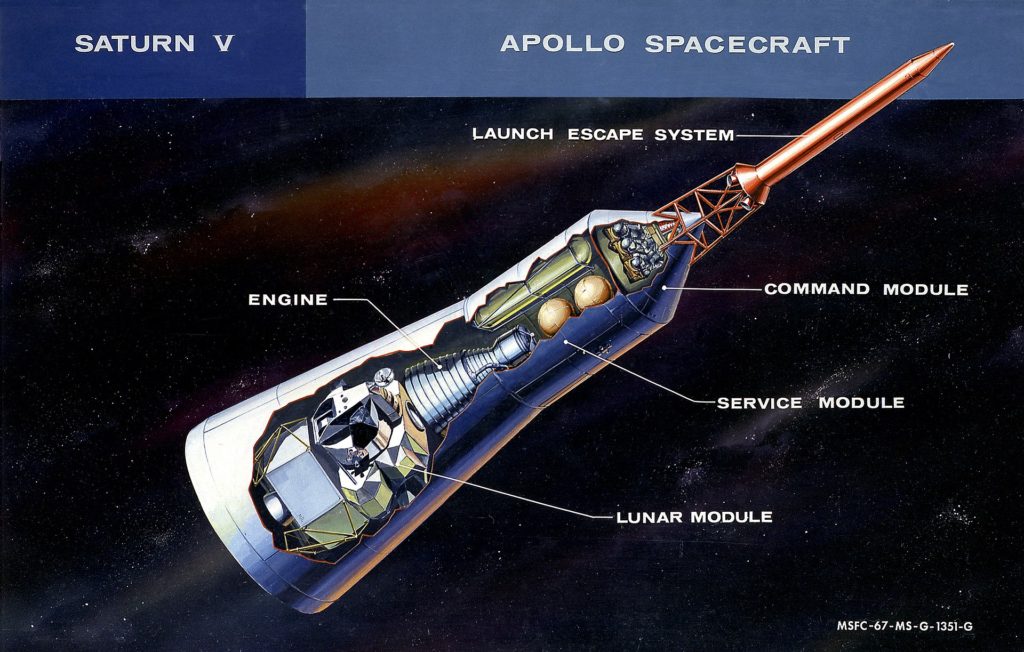

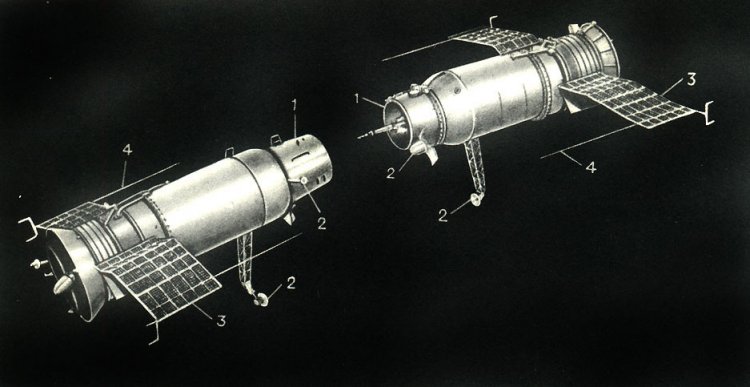

Originally planned as an Earth orbiting mission to check out the Lunar Module (LM) necessary to land astronauts on the Moon, delays in that vehicle’s development resulted in a radical change to the Apollo-8 mission profile.

As early as August, Apollo Programme manager Mr. George Low, suggested the idea of converting the first crew-carrying flight of the mighty Saturn 5 rocket into a flight to the Moon without a LM. His initial circumlunar flight concept soon became transformed into an even bolder proposal for a lunar orbit mission, as a counter to a possible lunar flight by Soviet cosmonauts, for which the Zond-5 and 6 missions are thought to be a precursor.

A telex sent to NASA's Manned Space Flight Network at the conclusion of the Apollo-7 mission, which refers to the future lunar mission

A telex sent to NASA's Manned Space Flight Network at the conclusion of the Apollo-7 mission, which refers to the future lunar mission

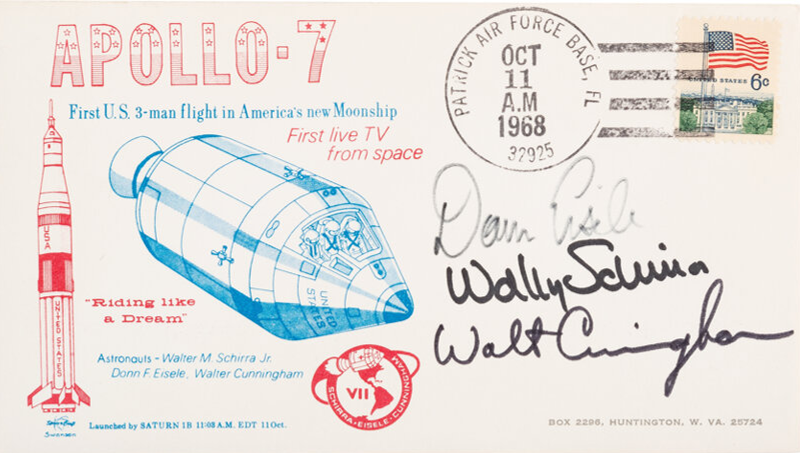

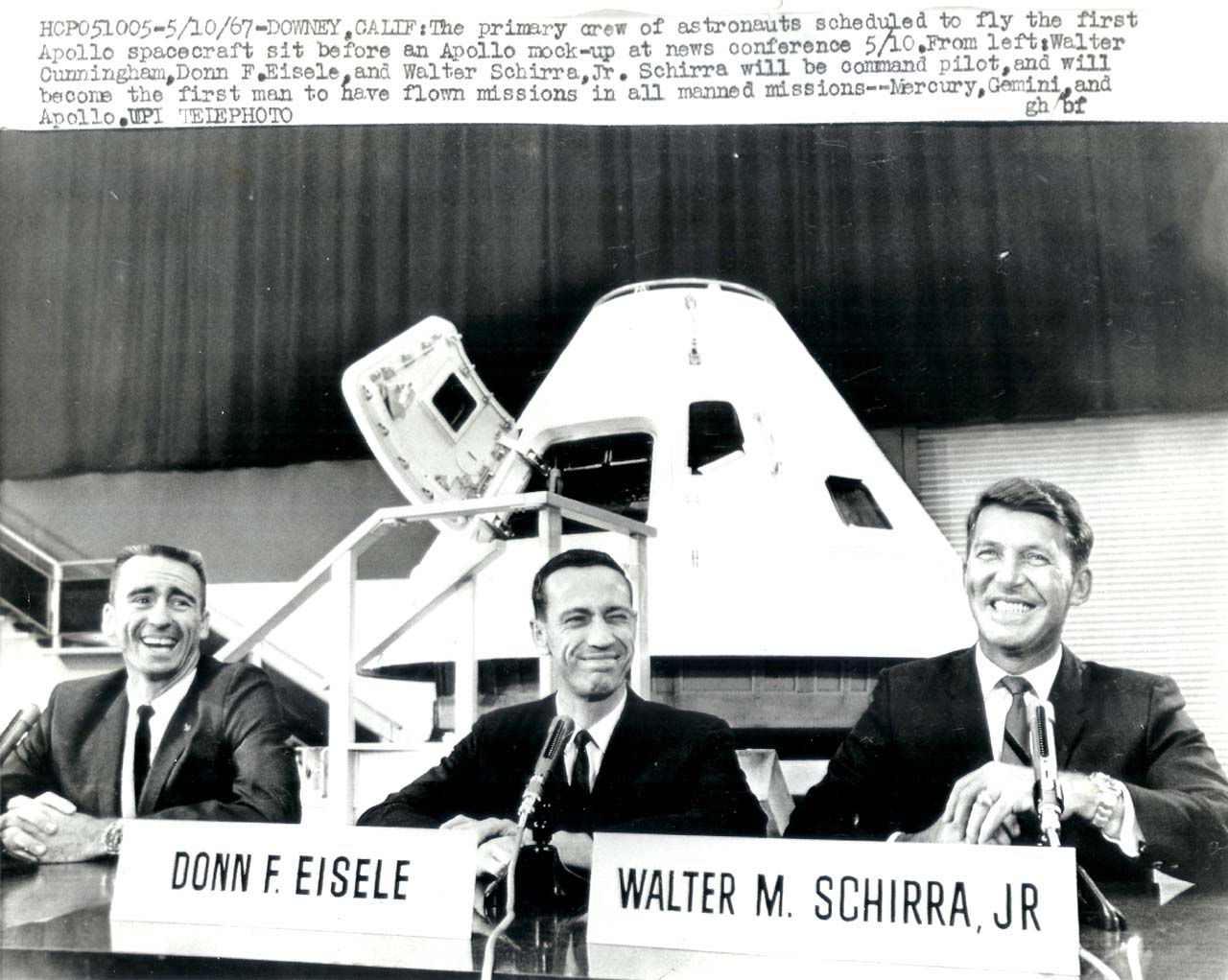

With the successful test flight of Apollo-7, the daring plan for Apollo-8 to orbit the Moon was publicly announced on 12 November. A successful flight around the Moon would demonstrate that a manned lunar landing was achievable, and hopefully beat the USSR to placing the first humans into orbit around the Moon.

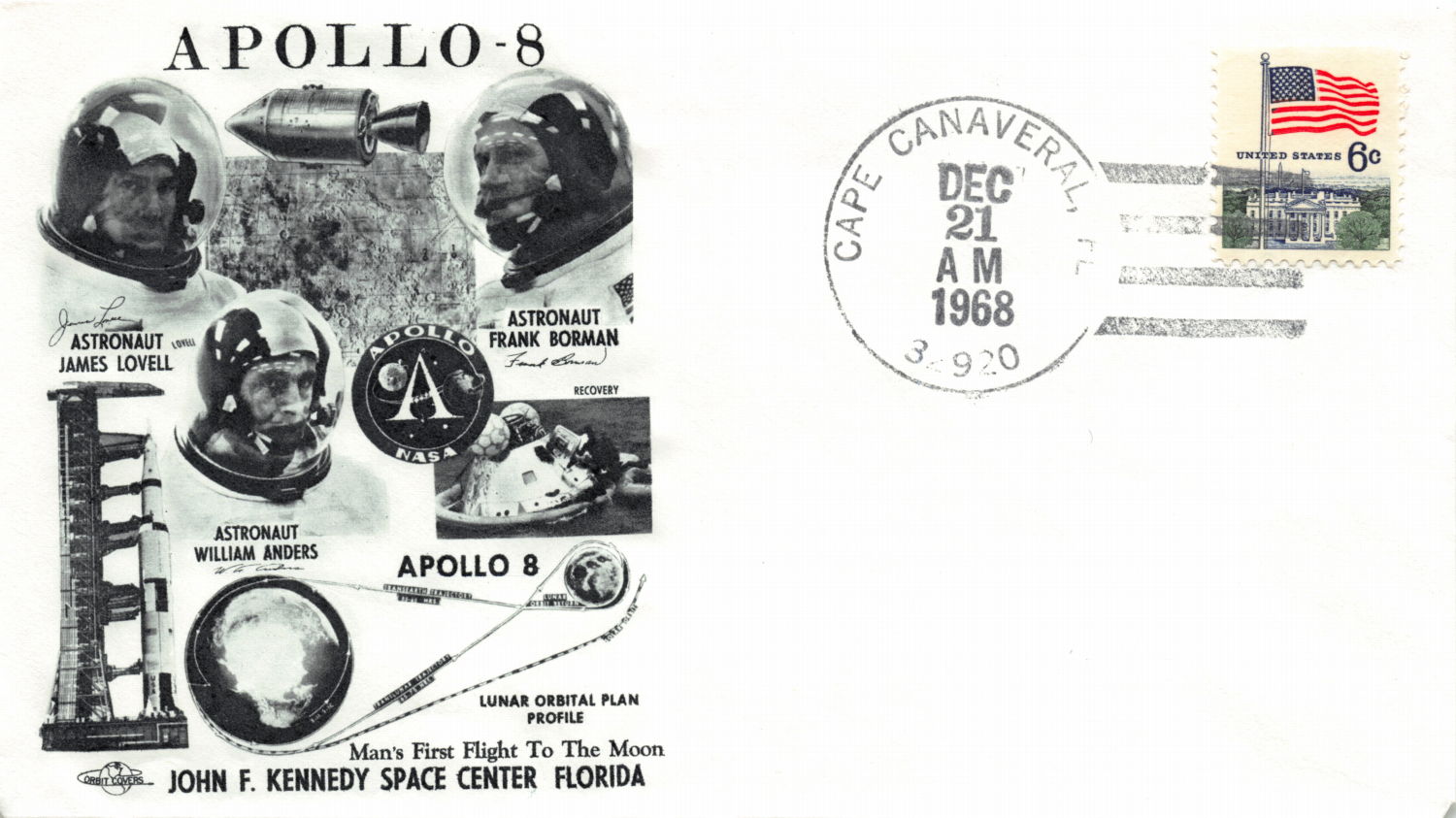

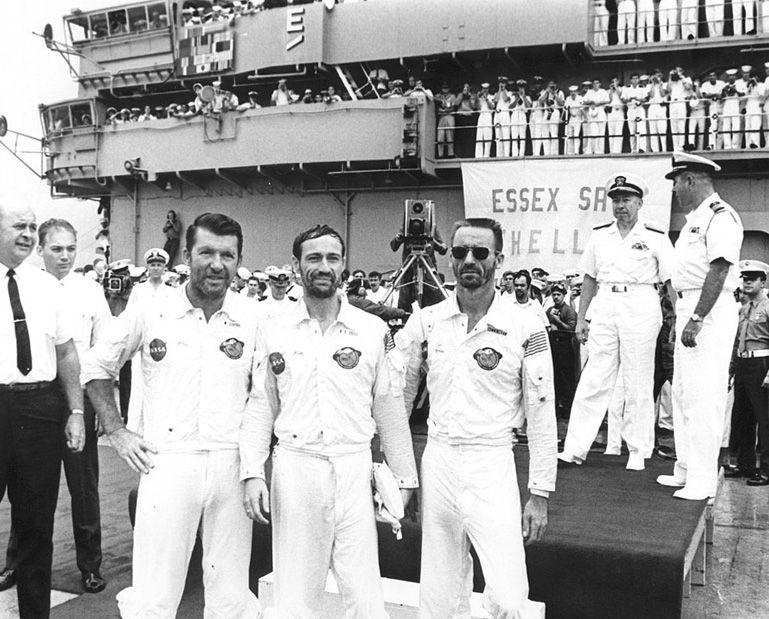

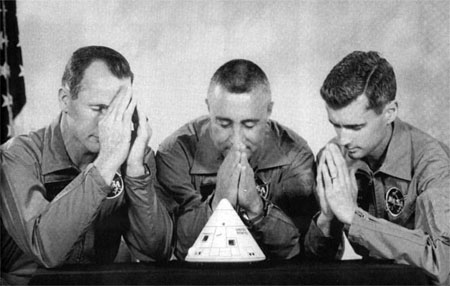

Swapping Crews

Director of Flight Crew Operations, Mr. Deke Slayton, planned early for the proposed change in the mission profile, bumping the original Apollo-8 crew to Apollo-9, since that crew had been training hard for the mission to check out the Lunar Module. Instead, the original Apollo-9 crew – Colonel Frank Borman, Captain James Lovell and Major William Anders, who had been training to test the Lunar Module in cislunar space, became the astronauts destined to fly the first manned mission to the Moon. While the new crew for Apollo-8 was announced on 19 August, the potential lunar flight plan was initially kept secret.

The Apollo-8 crew in front of the Command Module simulator. L-R Col. Borman, Major Anders, Capt. Lovell

The Apollo-8 crew in front of the Command Module simulator. L-R Col. Borman, Major Anders, Capt. Lovell

40-year-old Col. Borman, the mission commander, and Command Module (CM) Pilot Capt. Lovell (only 11 days younger than Borman), had previously flown together on the Gemini-7 mission, during which they set a long-duration record of 14 days in space. Lovell went on to command Gemini-12, while Borman served as the astronaut representative on the Apollo-1 Fire Investigation Board. The combined space experience of these two seasoned mission commanders undoubtedly played an important role in the success of this critical NASA mission.

Rookie astronaut Major Anders, the third member of the crew, is a former US Air Force fighter pilot. He holds an advanced degree in nuclear engineering and was selected as part of NASA’s third astronaut group, with responsibilities for dosimetry, radiation effects and environmental controls. Despite its lack on this flight, Anders was designated as Lunar Module Pilot and assigned the role of flight engineer, responsible for monitoring all spacecraft systems.

Uniquely Symbolic

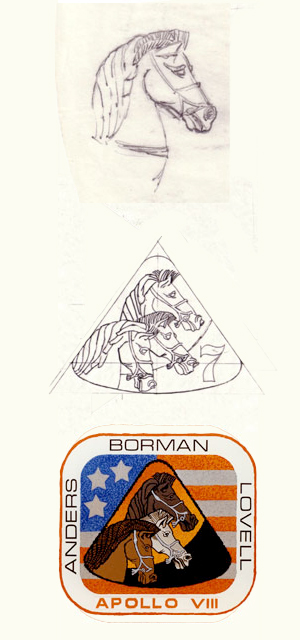

The unique design of the Apollo-8 mission patch has a simple elegance that perfectly symbolises the flight. The shape of the patch recalls the gumdrop shape of the Apollo CM, while the red figure 8 circling the Earth and Moon represents both the number of the mission and the free-return flight trajectory for a lunar mission.

Captain Lovell claims credit for the basic design of the patch, developing it during a flight from the Apollo spacecraft manufacturing facility in California back to Houston, after learning about the change in mission assignment.

Captain Lovell claims credit for the basic design of the patch, developing it during a flight from the Apollo spacecraft manufacturing facility in California back to Houston, after learning about the change in mission assignment.

However, he may have been inspired by earlier patch designs by Allen Stevens, who has previously been responsible for the Apollo-1 and Apollo-7 patches. Mr. Stevens used the CM shape on some of his early designs for Apollo-7. His design for the original Apollo-9 patch – that Col. Borman and his crew had apparently approved – also included a CM-shaped frame and was repurposed as an alternative Apollo-8 lunar mission design.

However, he may have been inspired by earlier patch designs by Allen Stevens, who has previously been responsible for the Apollo-1 and Apollo-7 patches. Mr. Stevens used the CM shape on some of his early designs for Apollo-7. His design for the original Apollo-9 patch – that Col. Borman and his crew had apparently approved – also included a CM-shaped frame and was repurposed as an alternative Apollo-8 lunar mission design.

I’ve heard it suggested that the figure-8 design element, representing mission number and lunar trajectory, may also have been influenced by the similar use of an 8 symbol to indicate a circumlunar trajectory on documents from the Mission Planning and Analysis Division (MPAD) at the Manned Spaceflight Centre.

This logo from NASA's MPAD may have inluenced the Apollo-8 patch design. What do you think?

This logo from NASA's MPAD may have inluenced the Apollo-8 patch design. What do you think?

Rumour has it that the Apollo-8 crew wanted to name their spacecraft, but –maintaining its long-held ban on such names – NASA would not allow it. Had they been given permission to do so, Columbiad (after the massive cannon that fires a projectile spacecraft to the Moon in Jules Verne's 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon) might have been the name the crew selected.

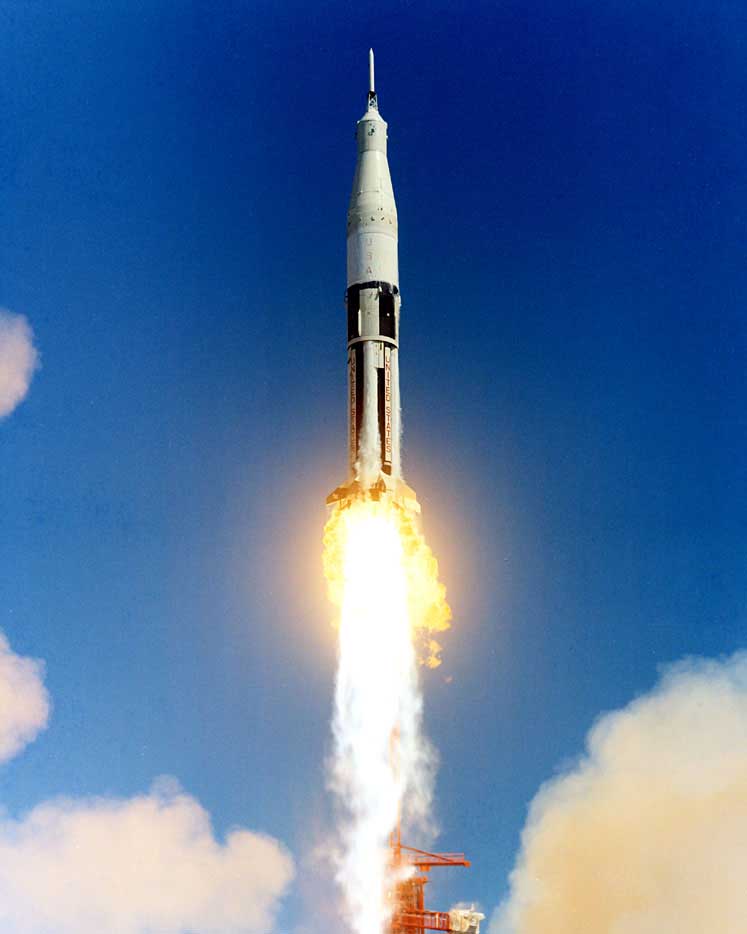

Countdown to a Historic Flight

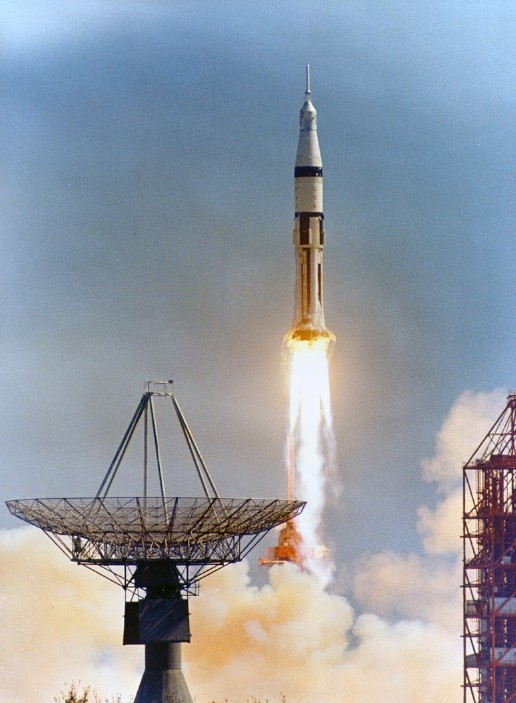

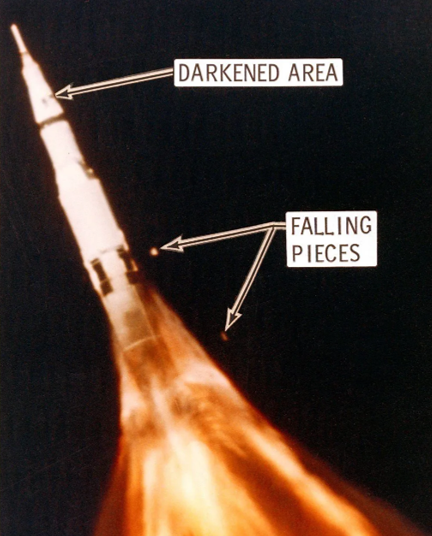

The un-manned Apollo-6 Saturn 5 test flight in April experienced major problems, including severe pogo oscillation while the first stage was firing, two second-stage engine failures, and the failure of the third stage to re-ignite in orbit. Resolving these issues was a priority before Apollo-8’s Saturn-5 launcher, AS-503, could leave the ground carrying human passengers.

Pogo oscillation was a serious concern: it could not only hamper engine performance, but the g-forces it created might even injure a crew. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Centre (MSFC) investigated the problems and determined the cause to be the similar vibration frequencies of the engines and the spacecraft, creating a resonance effect. AS-503 was therefore fitted with a helium gas system to absorb some of the vibration.

Similarly, MSFC engineers determined that fuel lines rupturing when exposed to vacuum and a mis-wired connection were the cause of the engine shutdowns. The use of suitably modified fuel lines on Apollo-8’s launch vehicle prevented these issues recurring.

The fact that the Saturn-5 thundered off Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Centre exactly as scheduled months earlier is a tribute to the 5,500 technicians and other personnel working behind the scenes to ready the launch vehicle and spacecraft for flight. Preparations for the launch were considered among the smoothest in recent years, although two equipment issues arising during the dress rehearsal countdown threatened to delay the commencement of the formal launch countdown on 16 December.

The historic first mission to the Moon was scheduled to launch at 12.51 GMT 21 December. This specific date and time would allow the crew to observe the site in the Sea of Tranquillity, where the first Apollo landing was planned to touch down, at the ideal Sun elevation of 6.7°, with shadows throwing the cratered lunar terrain into sharp relief.

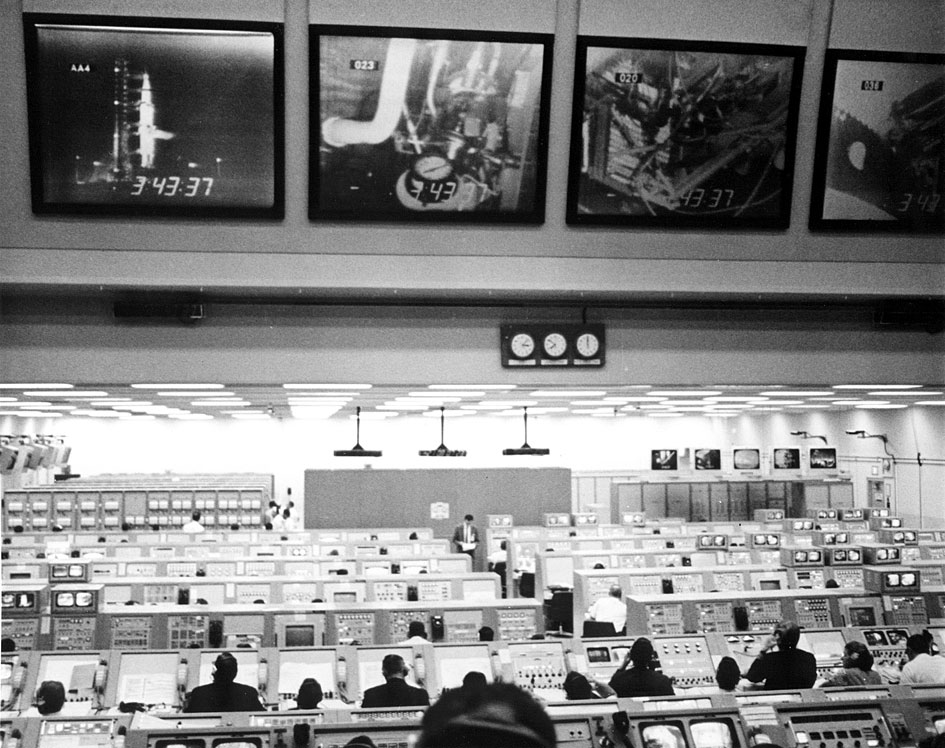

As a precaution, the 103-hour countdown commenced a day early to allow time for the correction of any unseen snags and keep the lift-off on schedule. Computerised systems, now a feature of the need to support the incredible complexity of the Saturn 5 launcher, provided comprehensive data to the launch controllers giving the “go”/”no go” calls prior to launch.

The computerised Launch Control Room at Kennedy Space Centre, about three hours before launch

The computerised Launch Control Room at Kennedy Space Centre, about three hours before launch

Avoiding the Flu – and Radiation Poisoning

With the so-called Hong Kong Flu epidemic sweeping the United States, NASA was taking no chances with the crew’s pre-launch health (especially following the issues created by astronaut Schirra’s head cold during Apollo-7). The astronauts were kept in isolation in quarters at the Kennedy Space Centre for more than a week before the flight and were immunised against the influenza virus – along with anyone likely to come into contact with them.

Emerging from pre-flight isolation into history, the Apollo-8 crew walk out to the astronaut transfer van, ready for their spaceflight

Emerging from pre-flight isolation into history, the Apollo-8 crew walk out to the astronaut transfer van, ready for their spaceflight

The astronaut’s pre-flight medical examination collected data for comparison with their post-flight examination. Since the Apollo-8 crew has been the first to pass through and beyond the protection of the Van Allen radiation belts, this comparison of pre- and post-flight medical data will reveal any physical changes or health effects resulting from the first human flight beyond Earth orbit.

Basic cross section of the radiation belts around Earth (not drawn to scale). The outer belt is composed of electrons, the inner belt comprises both electrons and protons.

Basic cross section of the radiation belts around Earth (not drawn to scale). The outer belt is composed of electrons, the inner belt comprises both electrons and protons.

Major Anders’ expertise in dosimetry and radiation effects has undoubtedly been relevant to this aspect of the mission, as each astronaut wore a personal radiation dosimeter which could return data back to NASA’s flight surgeons. The spacecraft also carried three passive film dosimeters recording the cumulative radiation to which the crew were subjected. Initial indications are that the radiation dosage received by the astronauts was at an acceptable level and should not preclude future missions to the Moon.

Apollo’s “Sun Screen”

Beyond the Van Allen Belts, the Apollo-8 crew was travelling in the realms of the intense and deadly radiations of deep space, particularly the streams of charged particles spewed out into the Solar System from solar flares. The astronauts would have been seriously at risk from radiation poisoning if a major solar event occurred during their spaceflight.

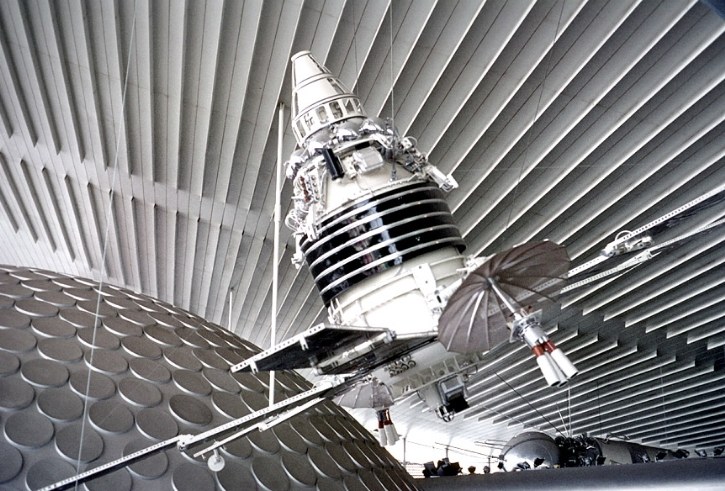

To ensure astronaut safety during lunar missions, NASA has established the world-wide Solar Particle Alert Network (SPAN). Stations in Houston, Texas, the Canary Islands, and Carnarvon, Western Australia, provide a 24-hour watch on the Sun, to spot dangerous solar activity. SPAN stations are operated by the US Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA), which also collects data from twelve satellites that monitor for deadly solar flares. This space-based early-warning system is comprised of four sun-orbiting Pioneer spacecraft (including Pioneers 6, 7 and 8 carrying cosmic ray detectors developed by Australian physicist Dr. Ken McCracken) and eight Earth-orbiting Vela nuclear test detection satellites.

The ESSA SPAN facility in Carnarvon, Western Australia, equipped with both optical and radio telescopes to observe the Sun

The ESSA SPAN facility in Carnarvon, Western Australia, equipped with both optical and radio telescopes to observe the Sun

ESSA aims to give NASA at least 24 hours’ warning of major solar eruptions, providing enough time enough to delay a launch or alter an orbit to protect the astronauts. Fortunately for Apollo-8’s important flight, the Sun smiled kindly and there was no dangerous solar activity, but future Apollo missions may be grateful for the early warning provided by NASA’s “Sun screen”.

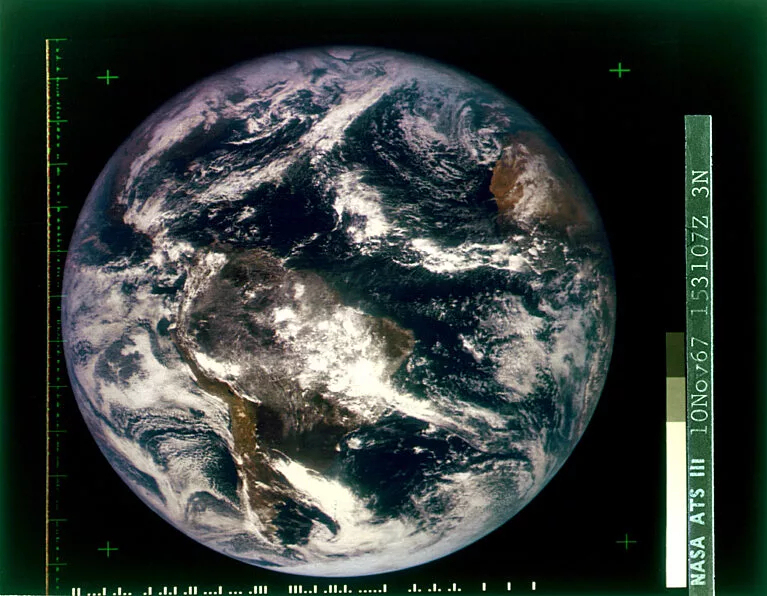

The Whole World was Watching

Television coverage of Apollo-8’s launch was the most extensive to date. The BBC, going “live” for the first time from Cape Kennedy, provided coverage to 54 countries, across Europe and beyond in 15 languages, in a broadcast whose complexity must have rivalled its role in the Our World satellite project. Seven television networks in Britain, the United States, Japan, Canada and Mexico, provided live coverage of the launch, with NASA’s ATS-3 satellite over the Atlantic providing transmissions to Europe and ATS-1 over the Pacific, serving Japan and the Philippines. Even the Communist nations of Eastern Europe were apparently able to watch the launch, although we in Australia could not.

All eyes were trained on the sky at the crowded press site at Kennedy Space Centre as Apollo-8 lifted off

All eyes were trained on the sky at the crowded press site at Kennedy Space Centre as Apollo-8 lifted off

To the Moon, Alice!

When Apollo-8 launched on 21 December, Gemini veterans Borman and Lovell found the ride “less demanding than Gemini from a ‘g’ standpoint, because it didn’t reach the high ‘gs’”, they had experienced on their earlier missions. However, the ride to orbit was still “powerful and noisy… and the stagings were really kind of violent.”

When Apollo-8 launched on 21 December, Gemini veterans Borman and Lovell found the ride “less demanding than Gemini from a ‘g’ standpoint, because it didn’t reach the high ‘gs’”, they had experienced on their earlier missions. However, the ride to orbit was still “powerful and noisy… and the stagings were really kind of violent.”

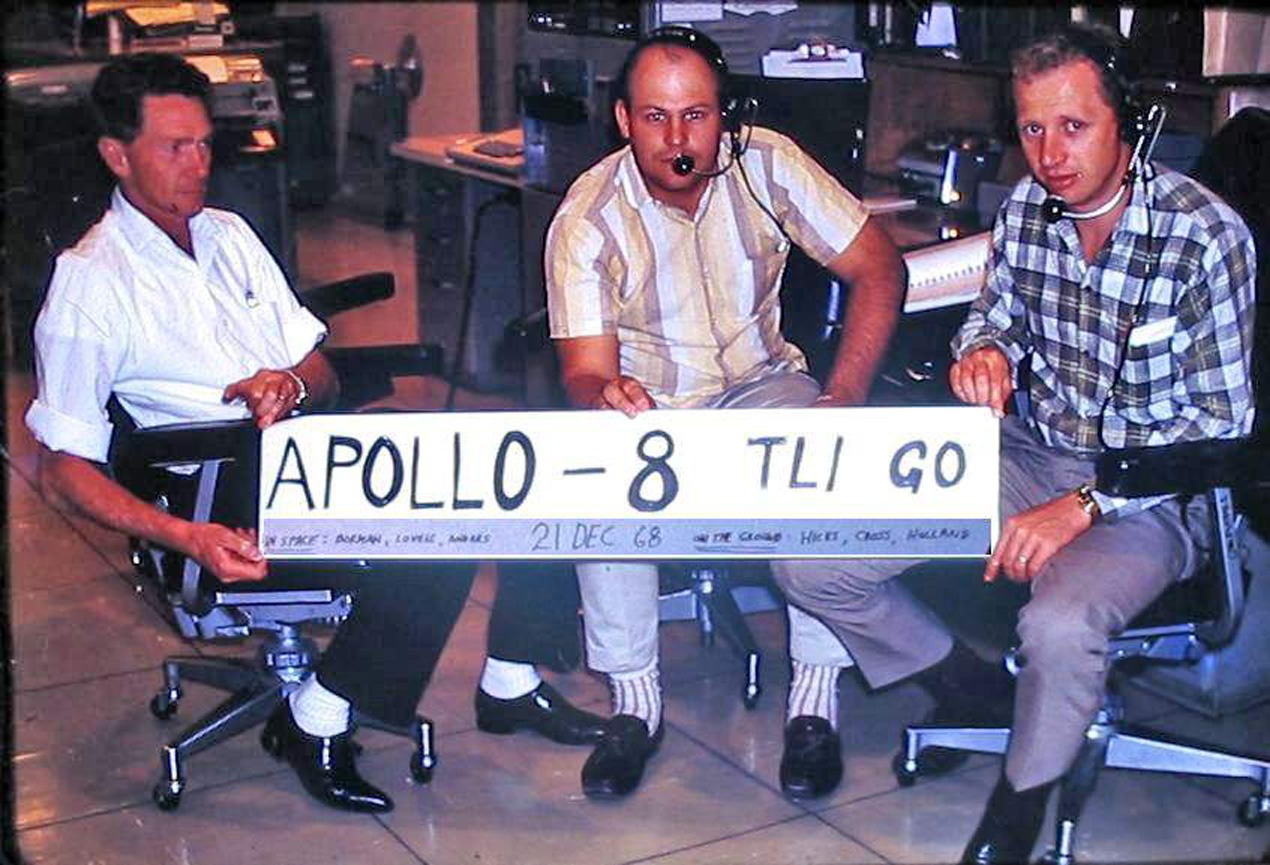

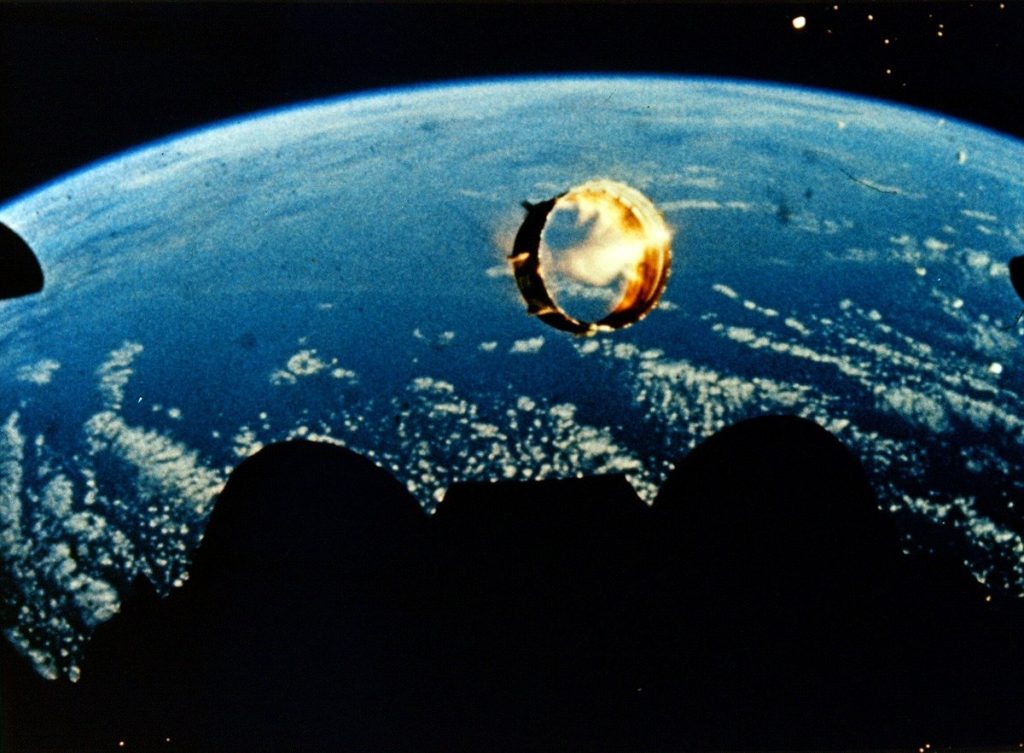

Apollo-8 entered Earth orbit with the third stage still attached, its engine needed for the Trans-Lunar Injection (TLI) burn to put the spacecraft on course to the Moon. For a little over two and a half hours every system of the Command Service Module (CSM) was thoroughly checked out in orbit, to ensure it was fully operational.

Staff at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station in Australia mark the first time humans have ventured beyond Earth orbit. The fine print of their sign reads:“In space: Borman, Lovell, Anders. On the ground: Hicks, Cross, Holland.”

Staff at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station in Australia mark the first time humans have ventured beyond Earth orbit. The fine print of their sign reads:“In space: Borman, Lovell, Anders. On the ground: Hicks, Cross, Holland.”

Then Mission Control gave Apollo-8 the crucial permission call “You are Go for TLI”. The S-IVB stage’s engine sent the first human mission to the Moon on its way out of Earth orbit, with the spacecraft reaching escape velocity (25,000 mph) in just five minutes! As it left the Earth, Apollo-8 was placed on a “free return” trajectory, that would ensure that lunar gravity would slingshot the spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth in the event of a failure of the CCSM’s powerful onboard engine. An amazing voyage was underway!

I am going to pause my recap of Apollo-8 at this point, and will take it up again in January, when what I anticipate will be amazing photographic imagery from the flight to the Moon and back becomes available. Please join me then. In the meantime, let me wish everyone on the Journey a Happy New Year' looking forward to an exciting 1969 – knowing that the Moon is now within our grasp!

![[December 28, 1968] A Christmas Gift to the World – Part 1 (Apollo 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Apollo-8-patch-672x372.png)

![[October 26, 1968] Phoenix from the Ashes (Apollo-7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Apollo-7-cover.jpg-672x372.png)

![[August 26, 1968] No time for a breath (Summer space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680826essa7-629x372.jpg)

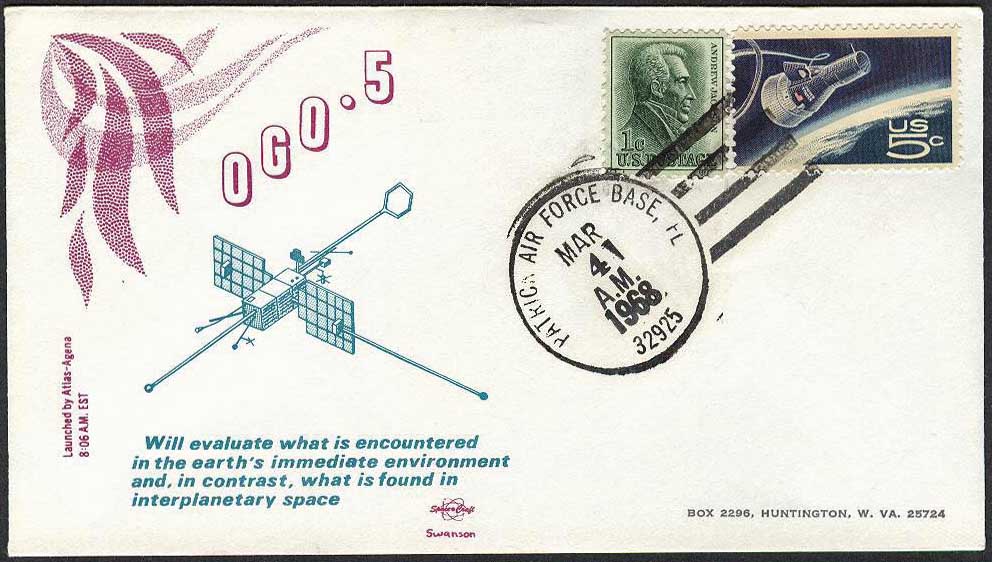

![[April 8, 1968] Ups, Downs and Tragedy: An Eventful Month in Space (Gagarin's crash, Zond-4, OGO-5, Apollo-6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680408gagarin-672x372.jpg)

![[January 24, 1968] On Track for the Moon (Apollo 5 and Surveyor 7]](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/apollo_5_patch-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1967] Still in the Race! (Apollo-4, Surveyor-6, OSO-4 and Cosmos-186-188)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Apollo-4-672x372.jpg)

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

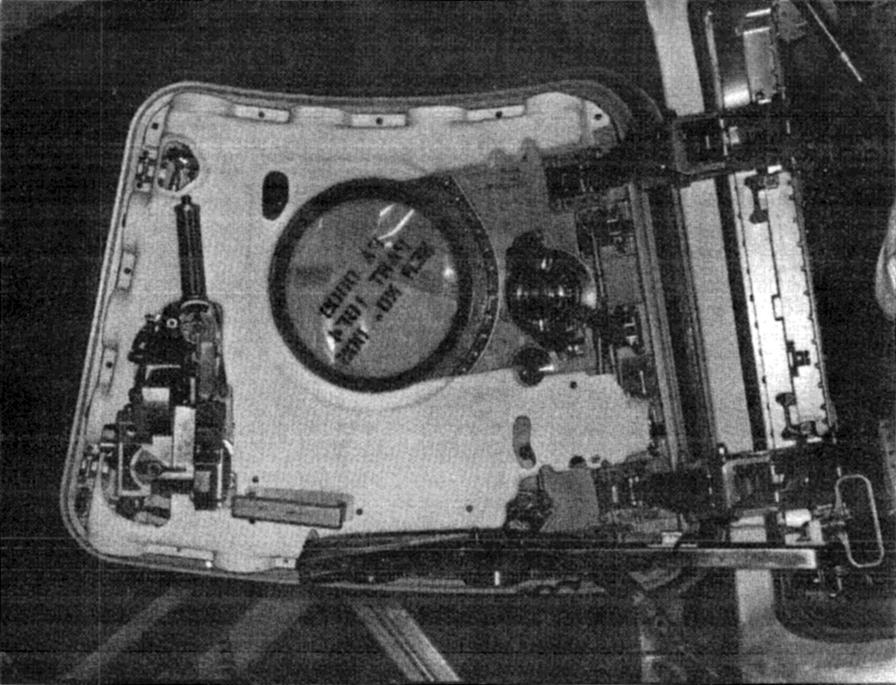

OSO-4 under construction

OSO-4 under construction

![[April 30, 1967] Strange New Worlds and Staid Old Ones (May 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1967] "Fire in the cockpit!" (The AS-204 Accident)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Apollo_1-Command_Module-after-fire-465x372.jpg)

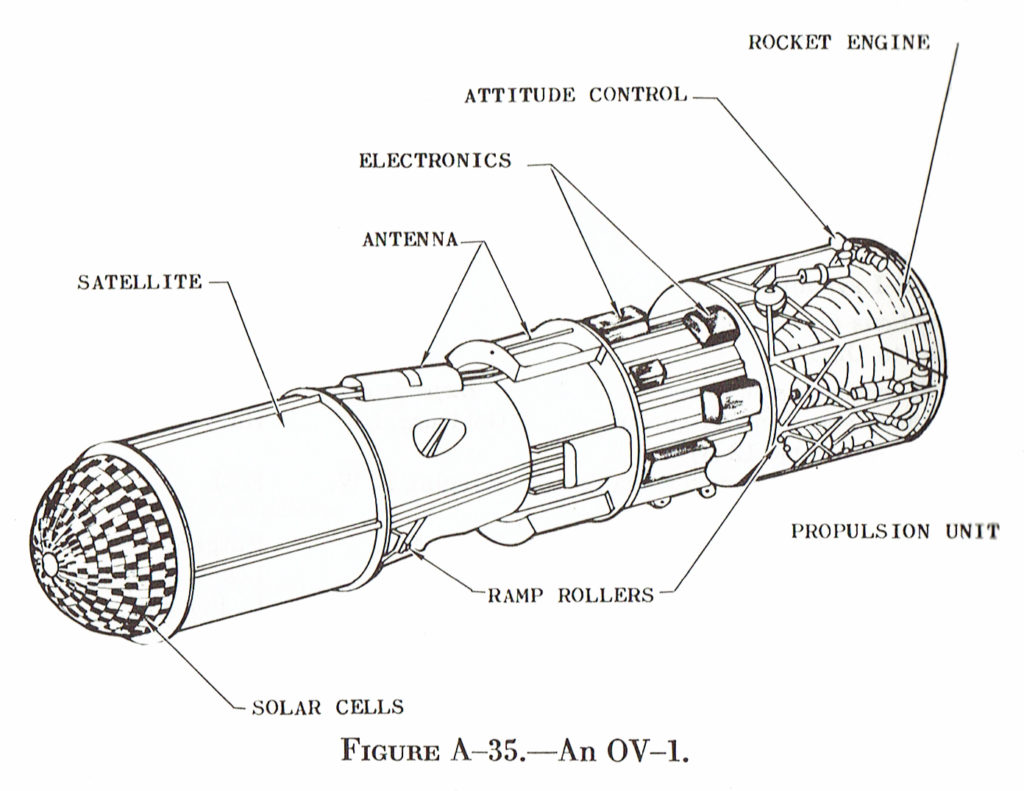

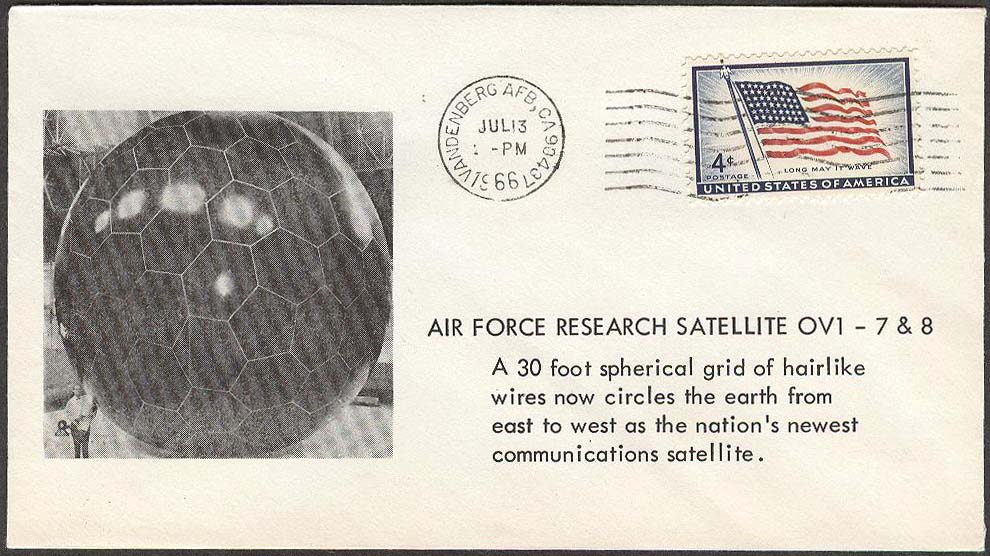

![[July 16, 1966] Onward and Upward! (Apollo, Australia, and OV)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660705launch4-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 30, 1964] Every journey begins… (Apollo's first flight!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640530apollo-672x372.jpg)