by Gideon Marcus

Remember the early days of the Space Race, when launches came about once a month, and there was plenty of time to ruminate over the significance of each one?

Those days are long past, my friends. Like every other aspect of this crazy modern world we live in, the pace of space missions is only accelerating. Just look at this grab bag of space headlines, any one of which might have been front page news just a few years ago:

Staring at the Sun

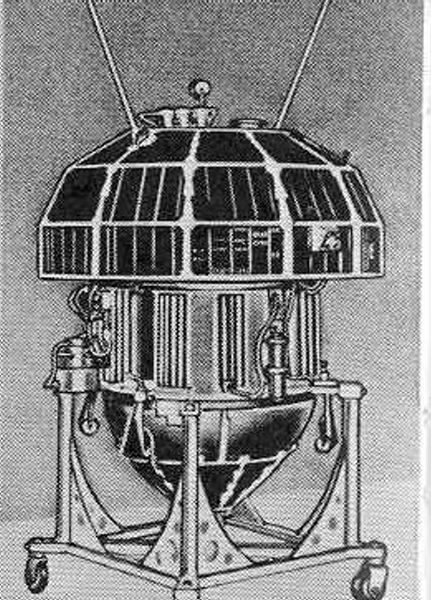

Three years ago, NASA launched the first of its "Observatory Class" satellites, the 200 kg Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO). Its mission was unprecedented: to get the first long-term observations of the Sun in all of the frequencies of the electro-magnetic spectrum, not just the narrow windows visible from the Earth's surface.

For two years, OSO gazed at the Sun with its thirteen instruments, dutifully reporting its findings to the ground. The observatory revolutionized our understanding of our neighborhood star, particularly in finding the correlation between solar flares and the little microflares that precede them.

OSO 1 went silent last May. Like nature, NASA abhors a vacuum — at least one without satellites floating through it! So on February 3, 1965, OSO 2 sailed into orbit to pick up where its predecessor had left off.

The new observatory only has eight instruments, but given that the weight of the craft is similar to that of OSO 1, I have to believe the new load-out is intentional. Moreover, OSO 2 has some neat developments. Its Ultraviolet spectrometer, Solar x-ray and UV telescope, and White-light coronagraph are all mounted on the "sail" of the spacecraft, and they can scan the disk of the sun from end to end, like a TV camera. That should allow for more precision in the measurements.

Also, OSO 2 has a digital telemetry system rather than the analog FM system of OSO 1. Digital systems are far less prone to error, and more information can be sent over any given length of time. The new system can dump 3 million bits of data in just 5.5 minutes.

Finally, OSO 2 is smarter — it can accept some 70 commands from the ground instead of just 8. Just what NASA scientists do with those commands, I don't know. Maybe OSO brews great coffee.

The most important thing about OSO 2 is the timing of its launch. Every 11 years, the Sun completes an output cycle, warbling from active to inactive status. 1965 is the Solar minimum, and this year marks a concerted international effort to watch the Sun from many different vantage points to take advantage of the opportunity.

You can bet OSO 2 will have some interesting data for us come 1966!

Requiem for a Vanguard

Hands over hearts, folks. On February 12, NASA announced that Vanguard 1 had gone silent, and the agency was finally turning off its 108 Mhz ground transceivers, set up during the International Geophysical Year. The grapefruit-sized satellite, launched March 17, 1958, was the fourth satellite to be orbited. It had been designed as a minimum space probe and, had its rocket worked in December 1957, would have been America's first satellite rather than its second. Nevertheless, rugged little Vanguard 1 beat all of its successors for lifespan. Sputniks and Explorers came and went. Vanguards 2 and 3 shut off long ago. Yet the grapefruit that the Naval Research Laboratory made kept going beep-beep, helping scientists on the ground measure the shape of the Earth from the wiggle and decay of Vanguard's orbit.

The satellite's cry had slowly become weaker as its solar cell-charged batteries failed. Finally, some time last year, Vanguard could be heard no more, though NASA kept listening for several more months. It's not all sad news, however: Vanguard 1 will remain in orbit for hundreds of years more, and it can still be optically tracked. That means it still has a long, useful life ahead of it, even now that it is mute.

Whole World in its Eyes

Here's a little TIROS tidbit. Remember TIROS 9? The first weather satellite launched into a polar orbit so it can see the whole Earth once a day as the planet rotates underneath?

We now have the very first picture of the world's weather. It won't be the last:

The joys of being regular

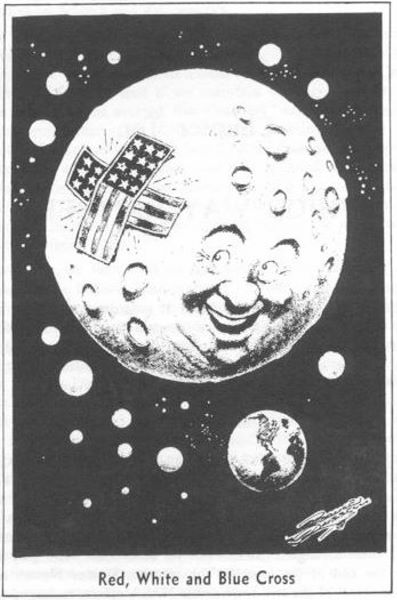

There was a time when space was a hit-and-miss affair. Seemed every time I opened the paper, there was news of yet another rocket blowing up. These days, we can practically take success for granted. Ranger 7 broke a six mission losing streak, the first two Gemini launches went swimmingly, TIROS has gone nine for nine.

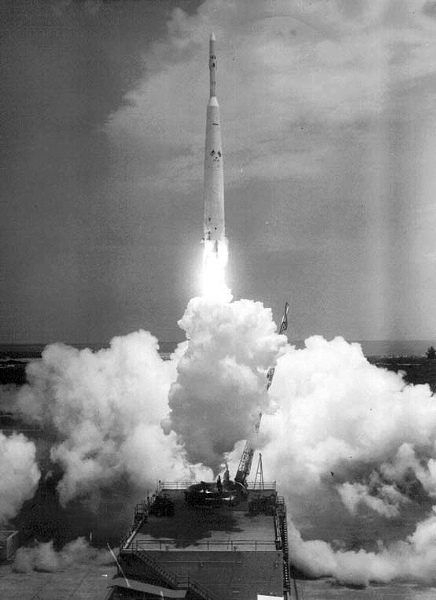

Similarly, the Saturn 1 rocket, the biggest booster ever made, has had an impeccable launch record. The lift-off on February 16 kept the streak going; the eight engine monstrosity delivered what I believe is the biggest satellite ever to be put into orbit.

Called Pegasus, it is an enormous cylinder with giant panels affixed to either side. The panels occupy some 2300 square feet, and their job is to measure the density of micrometeoroids in orbit over the course of a many-year lifespan.

It sounds pretty mundane when you reduce the mission to its bare essentials. Pegasus is like a big fly-catcher, spending its orbit running into space rocks. But it's not the experiment that's so exciting, but the idea that we can now loft giant structures with a single launch. Imagine that Pegasus was actually a space station module, and that it's wings were solar panels. Now imagine assembling a few of them together using a maneuverable spacecraft, perhaps a Gemini derivative…

Yes, America is just on the edge of being in the space construction business.

Scenes to Come

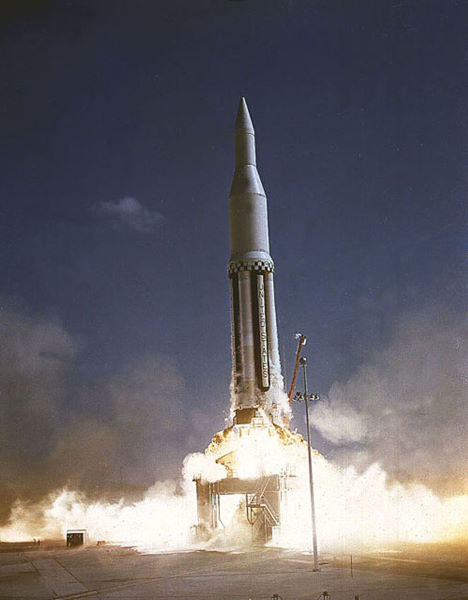

Yesterday (February 17, 1965), the eighth Ranger blasted off from Cape Kennedy, destination: Moon. If we've truly reached an era of reliability, we can expect the craft to hit its target on the morning of the 20th. Stay tuned — you'll read about it here first!

![[February 18, 1965] OSO Exciting! (February 1965 Space Roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650218oso2-576x372.jpg)

![[May 30, 1964] Every journey begins… (Apollo's first flight!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640530apollo-672x372.jpg)

![[February 5, 1964] That was the Month that Was (January's Space Roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640205echo2-672x372.jpg)