by Kaye Dee

As the race for the Moon heats up, the Gemini program is moving forward at a cracking pace –three months ago, Gemini VII completed its record breaking long-duration mission and NASA’s latest manned space mission, Gemini VIII launched just two days ago on March 16 (US time). By co-incidence, this was right on the 40th anniversary of the first successful launch of a liquid-fuelled rocket by American physicist Dr. Robert Goddard.

Goddard and his first liquid fuel rocket, launched forty years to the day before Gemini VIII. Developing a liquid-fuelled rocket was the necessary first step to making spaceflight a reality

But are things moving too fast? This latest Gemini flight was one of NASA’s most ambitious to date, slated for a 3-day mission to carry out the first rendezvous and docking and the United States’ second spacewalk. However, it was prematurely cut short after about 10 and a half hours, due to an in-flight emergency.

What was Supposed to Happen

Gemini VIII was intended to carry out the four rendezvous and docking manoeuvres originally planned for Gemini VI (the goals of that mission had to be changed due to the loss of its Agena target vehicle and instead it rendezvoused with Gemini VII). Being able to rendezvous and dock two spacecraft is a technique that is vitally important for the success of the Apollo programme, so NASA needs to be sure that it can reliably carry out these manoeuvres.

Gemini VIII approaches its Agena target vehicle in preparation for docking, practicing one of the crucial technologies of the Apollo programme

NASA also needs to gain more experience with extra-vehicular activity (EVA), or spacewalking, which is another crucial technique needed for Apollo. So far, the Gemini programme’s only EVA has been the one carried out by Ed White during the Gemini IV mission in June last year. Astronaut David Scott was scheduled to perform an ambitious spacewalk of over two hours, operating at the end of a 25-foot tether. He was supposed to retrieve a radiation experiment from the front of the Gemini's spacecraft adapter and activate a micrometeoroid experiment on the Agena target vehicle. Then it was planned to test a space power tool by loosening and tightening bolts on a work panel attached to the Gemini.

The most exciting part of the spacewalk would have taken place after Mission Commander Neil Armstrong undocked from the Agena for the first time. Major Scott would have tested an Extravehicular Support Pack (ESP), which contained its own oxygen supply and propellant for his Hand-Held Manoeuvring Unit. A 75-foot extension to his tether would have enabled Scott to carry out several manoeuvres in conjunction with the Gemini and Agena vehicles, while separated from them at distances up to 60 feet.

Very Experienced Rookies

Neil Armstrong (front) and David Scott departing the suit up trailer on their way to the launch pad. Behind Scott is Chief Astronaut Alan Shepard, the first American in space.

Gemini VIII’s crew are both first-time astronauts, but they have a wealth of flight experience between them. Mission Commander Neil Armstrong is the first American civilian in space, and a highly experienced test pilot. Before being selected for NASA’s second group of astronauts, Mr. Armstrong was a Naval aviator during the Korean conflict and then an experimental test pilot with NASA’s predecessor the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which he joined in 1955. He developed a reputation as an excellent engineer, a cool-headed clear-thinker, and an outstanding test pilot with nerves of steel, all of which helped him survive a number of dangerous flight-test incidents. Included in his experience are seven flights aboard the X-15 hypersonic research aircraft.

Gemini VIII Pilot David Scott is a major in the US Air Force, and the first member of the third astronaut group to make a spaceflight. Scott saw active duty in Europe before gaining both a Master of Science degree in Aeronautics/Astronautics and the degree of Engineer in Aeronautics/Astronautics from MIT in 1962. He joined the US Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in 1962 and was selected as an astronaut in October 1963.

A Spectrum of Objectives

Gemini VIII's mission patch. Look closely at the spectrum to see the text.

Now that mission patches seem to have become a standard part of each Gemini flight (after being introduced by the Gemini V crew), Armstrong and Scott designed their mission patch to feature a colour spectrum, which is shown as being produced by the light of two stars – Castor and Pollux, the two brightest stars in the constellation of Gemini – refracted through a prism. The spectrum symbolises “the whole spectrum of objectives” that they planned to accomplish on Gemini VIII, which included various science and technology experiments in addition to the docking and spacewalking activities. Looking closely at the spectrum, you can see that its lines have been drawn to represent the astronomical symbol for the constellation Gemini, as well as the Roman numeral VIII.

Things Go to Plan

The original Gemini VIII plan was for a three-day mission and at first everything seemed to be going perfectly. One hundred minutes before Gemini VIII, an Atlas rocket lifted off from Launch Pad 14 at the Cape carrying the Agena target vehicle. Unlike Gemini VI, this time the launch was successful, placing the Agena into a 161 nautical-mile circular orbit. Once it was certain that the Agena was safely in orbit, Gemini VIII lifted off from the nearby Pad 19: its launch, too, went without any problems.

A composite image combining the lift-off of the Atlas Agena and Gemini VIII

After an orbital “chase” of more than three and a half hours, Armstrong and Scott had their target in sight: they could visually spot it when they were about 76 nautical miles away. Then, at 55 nautical miles, the computer completed the rendezvous automatically.

Before docking with the Agena, the astronauts spent 35 minutes visually inspecting it, to ensure that it had suffered no damage from the launch. Then Armstrong started to move towards the Agena at 3.15 inches per second. In a matter of minutes, the Agena’s docking latches clicked: the first docking by a manned spacecraft had been successfully completed! Mission Commander Armstrong described the docking as “a real smoothie” and said that the Agena felt quite stable during the manoeuvre. NASA has now proved that it can achieve a critical technique needed for the Apollo Moon landings.

Things Don’t Go to Plan

The docking may have been a smoothie: however, what followed was anything but! Mission Control seems to have had some suspicions that the Agena's attitude control system could malfunction (my friends at Woomera say there was a possibility that the Agena’s onboard computer might not have the correct program stored in it), because the crew were reminded of the code to turn off the Agena’s computer and advised to abort the docking straight away if there were any problems with the target vehicle.

A close-up view as Gemini VIII approaches its Agena target vehicle.

As Gemini VIII lost radio contact with Houston (in a part of its orbit where it was out of range of any of the tracking stations on the ground), the Agena began to execute one of its stored test programs, to turn the two docked spacecraft. That’s when the emergency began! While the full details of the emergency are not yet known, it seems that the Agena started to roll uncontrollably, causing the docked spacecraft to gyrate wildly, making a full rotation every 10 seconds. The situation seems to have been pretty desperate, to judge from some communications picked up by monitors at the Radio Research Institute of the Japanese Postal Services.

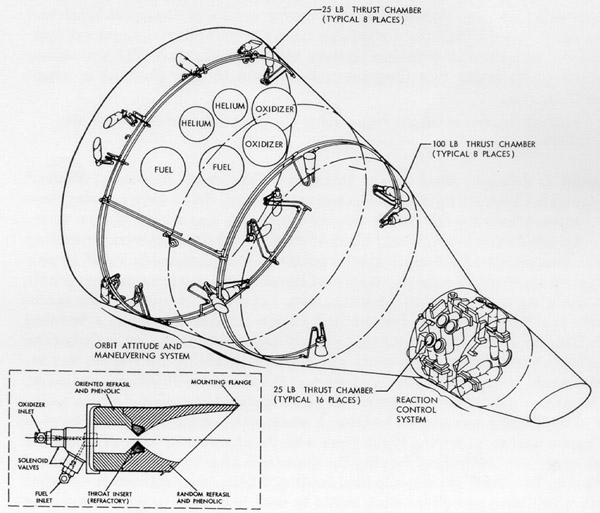

Armstrong has reported that he used the Gemini capsule’s orbital attitude and manoeuvring system (OAMS) thrusters to stop the tumbling, but the roll immediately began again. As he struggled to control the rotating vehicles Armstrong noticed that the OAMS fuel dropped quickly, hinting that perhaps the problem was with the Gemini, rather than the Agena.

Diagram showing the location of the OAMS thrusters and the Re-entry Control System thrusters (incorrectly identified as "Reaction Control System")

Then They Get Worse!

Armstrong and Scott decided to undock from the Agena, apparently concerned that the high spin-rate might damage the spacecraft or possibly cause the Agena, still loaded with propellant, to rupture or explode. It turns out, though, that the Agena’s mass must have been actually damping the rotation, because as soon as Gemini VIII undocked it began to tumble even more rapidly, making almost a full end over end rotation per second! The issue was definitely with the spacecraft, and it was an extremely dangerous one. At that rate of spin, the astronauts’ vision became blurred and they have said they were in danger of blacking out!

CapCom Jim Lovell (left) and astronaut Bill Anders following reports from Gemini VIII during the crisis

It was only at this point that Gemini VIII came back into contact with Mission Control, via the tracking ship USNS Coastal Sentry Quebec, stationed southwest of Japan. Armstrong sure is a quick thinker, though. He disengaged the OAMS system and used the re-entry control system (RCS) to finally halt the spin and regain control of Gemini VIII. However, doing this used up almost 75% of the re-entry manoeuvring fuel.

Emergency Abort!

Gemini mission rules dictate that a flight has to be aborted once the RCS is activated for any reason. With so much of the RCS fuel already consumed, and with no guarantee that the tumbling might not occur again, Flight Director John Hodge (on his first mission as Chief Flight Director, too!), quickly decided to abort the mission and bring Gemini VIII back to Earth.

Hodge decided to bring Gemini VIII home after one more orbit, so that secondary recovery forces in the Pacific could be in place. Re-entry occurred over China, out of range of NASA tracking stations, but US Air Force planes spotted the spacecraft as it descended towards its landing site about 430 nautical miles east of Okinawa. Three para-rescuers were dropped to attach a flotation collar to the capsule and stay with the astronauts until the recovery ship arrived.

Armstrong, Scott and their para-rescuers waiting for the arrival of the recovery ship

Initial reports are that, though exhausted, the crew were in good health when they landed, and they opened the Gemini hatches, ate some lunch, and relaxed in the sun with the para-rescuers while waiting for the recovery ship Leonard F Mason to arrive. Maybe the lunch wasn’t such a good idea, as I’ve heard that the crew and their rescuers were all a bit seasick by the time the ship reached them three hours later.

NASA officials met with the Gemini VIII crew in Japan for a preliminary debriefing, and Armstrong and Scott, together with Gemini VIII are now on their way back to the US. Hopefully, an accident investigation will soon reveal exactly what went wrong and why, causing NASA’s first in-flight emergency. But what we already know is that Armstrong and Scott behaved with cool competence in an extremely stressful and dangerous situation and NASA’s emergency procedures enabled the astronauts to be brought home quickly and safely. Everyone involved should be congratulated for demonstrating that even a crisis can be an important stepping-stone on the road to the Moon!

Safe and sound aboard the U.S.S. Leonard F. Mason

![[March 18, 1966] Taking Gemini for a Spin (Gemini 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Gemini-8-Approaching-rendezvous-672x372.jpg)