by Kaye Dee

by Kaye Dee

As we approach the first anniversary of the shocking loss of the crew of

Apollo 1, the success of the recent Apollo 5 mission reminds us that the spirit of Grissom, White and Chaffee lives on as NASA continues developing and testing the technology to make a manned lunar landing a reality.

Apollo 1's Legacy

Apollo 1's Legacy

Although the fire that engulfed Apollo 1 and killed its crew destroyed its Command Module, the accident took place on the launchpad during a launch simulation, and fortunately the Saturn IB booster intended to loft that mission into orbit remained undamaged. Because that AS-204 vehicle was the last Saturn IB with full research and development instrumentation, NASA decided that this rocket would be re-assigned to Apollo 5, the much-delayed first test flight of the Lunar Module – the spacecraft essential for successfully landing astronauts on the Moon – while manned Apollo missions continue on hold.

From LEM to LM

The spacecraft we now call the Lunar Module (LM) became part of the Apollo programme in

1962, when NASA decided to adopt the technique of lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) for its Moon landing missions. First proposed in 1919 by Ukrainian engineer and mathematician Yuri Kondratyuk, the LOR technique uses two spacecraft that travel together to the Moon and then separate in lunar orbit, with a lander carrying astronauts from orbit to the Moon’s surface. The LOR method allows the use of a smaller and lighter lander than the large, all-on-one spacecraft originally proposed for Apollo, and also provides for greater flexibility in landing site selection.

An early diagram comparing the size of a lunar landing vehicle using the Direct Ascent method of reaching the Moon and a LOR lunar excursion vehicle

An early diagram comparing the size of a lunar landing vehicle using the Direct Ascent method of reaching the Moon and a LOR lunar excursion vehicle

The version of lunar orbit rendezvous suggested to NASA by engineer John C. Houbolt called for a landing vehicle consisting of

two parts: a landing stage, that would accomplish the descent from orbit and remain on the Moon’s surface, and an ascent stage that would carry the astronauts back to the main spacecraft in orbit. This design gave us the Command Service Module as the Moon orbiting spacecraft, and what was originally called the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM, pronounced as a word, not as the individual letters) as the vehicle that would land astronauts on the Moon.

Dr. Houbolt illustrating the main spacecraft needed for his Lunar Orbit Rendezvous proposal for the Apollo programme

Dr. Houbolt illustrating the main spacecraft needed for his Lunar Orbit Rendezvous proposal for the Apollo programme

In June 1966, NASA changed the name to Lunar Module (LM), eliminating the word “excursion”. My friends at the WRE tell me that this was because there were concerns that using “excursion” might make it sound like the lunar missions were frivolous, and so reduce support for the Apollo programme! Despite the official name change, the astronauts, as well as staff at Grumman, still call it “the lem”, which certainly feels easier to say.

Delays…Delays…

However, the two-stage LEM/LM has proved much harder to develop and manufacture than the contractor Grumman originally anticipated, because of the complexity and level of reliability required of the hardware. Originally, NASA planned for the automated test flight of LM-1, the first Lunar Module, to occur in April 1967, but the delivery of the spacecraft was repeatedly delayed: the two stages of LM-1 did not arrive at Cape Kennedy until late June last year.

The separately-crated stages of LM-1 arriving at Kennedy Space Centre on board a Super Guppy cargo plane. The stages were mated to each other four days later

The separately-crated stages of LM-1 arriving at Kennedy Space Centre on board a Super Guppy cargo plane. The stages were mated to each other four days later

A team of 400 engineers and technicians then checked out the spacecraft to ensure that it met specifications. The discovery of leaks in the ascent stage propulsion system meant that the ascent and descent stages were demated and remated multiple times for repairs between August and October. LM-1 was finally mounted on its Saturn IB booster on 19 November and a launch date was set for the latter part of January 1968.

LM-1, encased in its SLA, being hoisted up for mounting on its launch vehicle

Lift Off at Last!

LM-1, encased in its SLA, being hoisted up for mounting on its launch vehicle

Lift Off at Last!

Although the launch was delayed for 10 hours when the countdown was held up by technical difficulties, Apollo 5 finally lifted off on 22 January 1968 (23 January for us here in Australia). The mission was designed to test the LM's descent and ascent propulsion systems, guidance and navigation systems, and the overall structural integrity of the craft. It also flight tested the Saturn V Instrument Unit.

Because they would not be needed during the Apollo 5 test flight, LM-1 had no landing legs, which helped to save weight. NASA also decided to replace the windows of LM-1 with aluminium plates as a precaution, after one of the windows broke during testing last December. Since the mission was of short duration, only some of LM-1’s systems were fully activated, and it only carried a partial load of consumables.

LM-1's "legless" configuration is clearly seen in this view of it during checkout at Kennedy Space Centre

LM-1's "legless" configuration is clearly seen in this view of it during checkout at Kennedy Space Centre

The Apollo 5 flight did not include Command and Service Modules (CSM), or a launch escape tower, so pictures of the launch vehicle show it to look more like its predecessor

AS-203 than

AS-202, which tested the CSM. The Apollo 5 stack had an overall height of 180ft and weighed 1,299,434 lbs. The LM was contained within the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adapter (SLA), located just below the nose cap of the rocket. The SLA consists of four panels that open like petals once the nose cap is jettisoned in orbit, allowing the LM to separate from the launcher.

The Saturn IB worked perfectly, inserting the second stage and LM into an 88-by-120-nautical-mile orbit. After the nose cone was jettisoned, LM-1 coasted for 43 minutes 52 seconds, before separating from the SLA into a 90-by-120-nautical-mile orbit. NASA’s Carnarvon tracking station in Western Australia tracked the first six orbits of the mission, while the new Apollo tracking station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, followed LM-1’s first orbit.

Putting LM-1 Through its Paces

Since it had no astronaut crew, the LM-1 test flight had a mission programmer installed, which could control the craft remotely. The first planned 39-second descent-engine burn commenced after two orbits, only to be aborted by the Apollo Guidance Computer after just four seconds, as the spacecraft was not travelling at its expected velocity. Exactly why this occurred is now being investigated. Of course, if there had been a crew onboard, the astronauts would probably have been able to analyse the situation and decide whether the engine should be restarted.

Instead, Mission Control, under Flight Director Gene Kranz, decided to conduct the engine and "fire-in-the-hole" tests under manual control, as without these test firings the mission would be deemed a failure. The "fire in the hole" test verified that the ascent stage could fire while attached to the descent stage, a procedure that will be used to launch from the Moon’s surface, or in the event of an aborted lunar landing. It involves shutting down the descent stage, switching control and power to the ascent stage, and firing the ascent engine while the two stages are still mated.

Apollo 5 Flight Director Gene Kranz (right) with future Lunar Module crew Astronauts McDivitt (left) and Schweickart (centre) discussing LM-1's control issues

Apollo 5 Flight Director Gene Kranz (right) with future Lunar Module crew Astronauts McDivitt (left) and Schweickart (centre) discussing LM-1's control issues

Both the ascent and descent engines were fired multiple times during the flight to demonstrate that they could be restarted after initial use. Eight hours into the mission, a problem with the guidance system did cause the ascent stage to spin out of control, but the vital engine test burns had been completed by then. LM-1 also demonstrated its ability to maintain a stable hover, and the guidance and navigation systems controlled the spacecraft's attitude and velocity as planned.

At the conclusion of the flight testing, the separated ascent and descent stages were left in a low orbit, with the anticipation that atmospheric drag would naturally cause their orbits to decay so that the craft would re-enter the atmosphere. The ascent stage re-entered and was destroyed on 24 January, but as I write the descent stage is still in orbit.

Another Step on the Road to the Moon

NASA considers that the LM performed well during its test flight, and have deemed Apollo 5 a success. One wonders now if the second unmanned test flight with LM-2, planned for later this year, will need to go ahead. NASA also plans to return astronauts to space with a test flight of the redesigned Command Module in September this year. Once that goal is accomplished, every part of the Apollo system will have been tested in spaceflight and it will finally be “Go!” for astronauts to shoot for the Moon. I can’t wait!

Lunar map showing the landing sites of all the successful Surveyor missions

So Long Surveyor!

Lunar map showing the landing sites of all the successful Surveyor missions

So Long Surveyor!

As the Apollo programme powers forward, the last of NASA’s automated lunar exploration programmes is coming to an end, with Surveyor 7 now in operation on the Moon. The Surveyor project was developed with the goal of demonstrating the feasibility of soft landings on the Moon's surface, ensuring that it would be safe for Apollo crews to touch down in their Lunar Modules. The Surveyor landings have complemented the Lunar Orbiter programme (which drew to a close in the latter part of last year), which imaged the Moon from orbit, mapping the lunar surface and providing detailed photographs of many proposed Apollo landing sites.

Making It Safe for a LM Landing

Of the seven Surveyor missions, five achieved their objectives, returning valuable data and images from the lunar surface.

Surveyor 1, launched on 30 May (US time) in 1966, was the first American spacecraft to soft land on the Moon (following the successful landing of the USSR’s Luna 9 on 31 January that year), returning 11,237 images of the lunar surface. Unfortunately, its successor, Surveyor 2, failed in September 1966, impacting onto the lunar surface when a malfunction of the guidance system caused an error in the mid-course correction as it travelled to the Moon.

Surveyor 1's panorama of the lunar surface, which captured its shadow, cast by the light of the Earth

Surveyor 3

Surveyor 1's panorama of the lunar surface, which captured its shadow, cast by the light of the Earth

Surveyor 3, which lifted off on 17 April 1967, was the first to conduct in-situ experiments on the lunar soil, using its extendable arm and scoop. The spacecraft also returned over 6,000 images, including the famous "Surveyors Footprint" shot, showing its footpad on the lunar surface. The probe had a lucky escape as it tried to land: a problem with its descent radar caused the descent engine to cut off late, resulting in the lander bouncing twice on the lunar surface before settling down to a final safe landing!

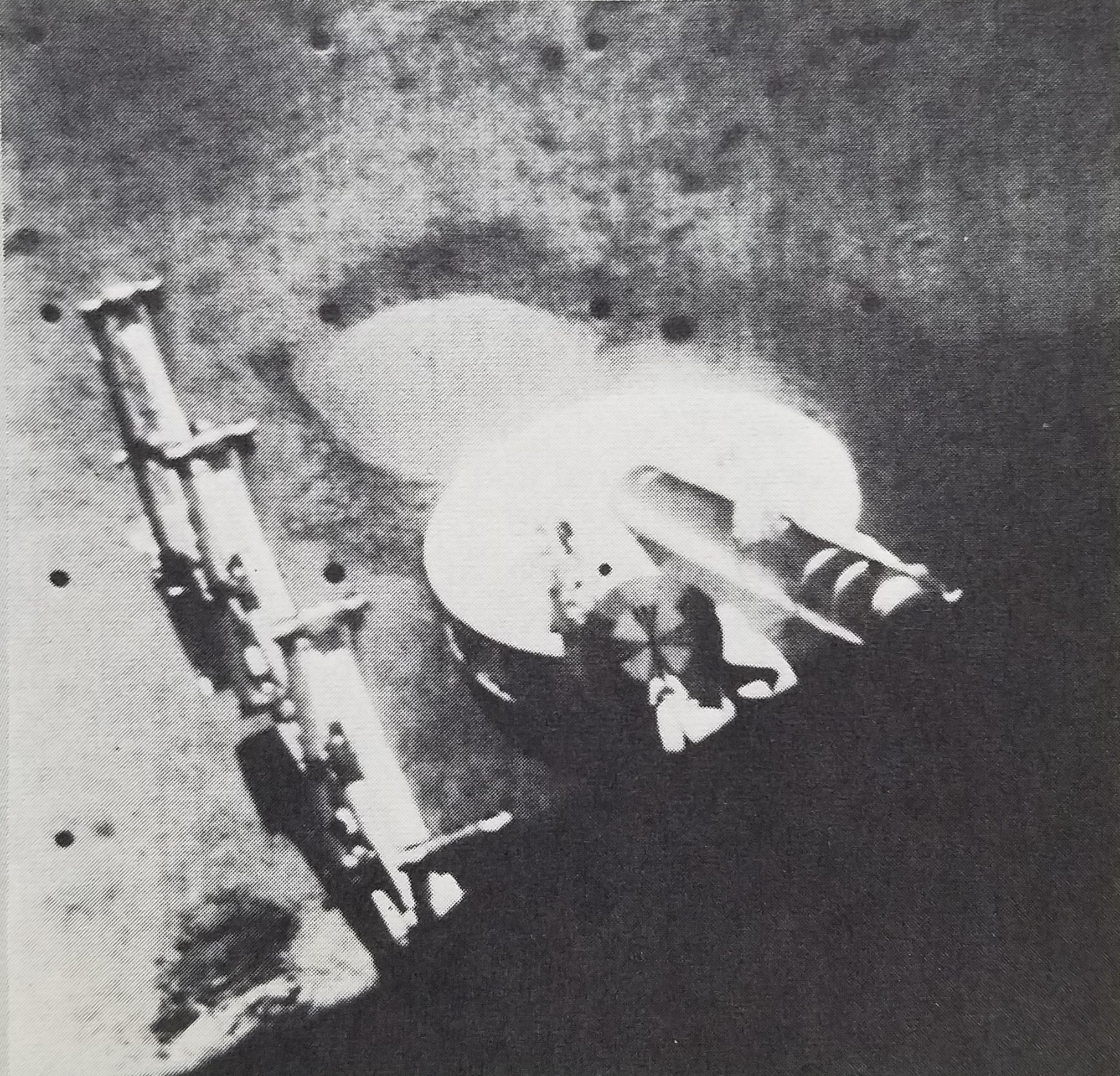

Surveyor 3's footprint and footpad on the lunar surface, showing how it bounced on landing. The extendable arm and scoop are visible on the left of the picture

Surveyor 3's footprint and footpad on the lunar surface, showing how it bounced on landing. The extendable arm and scoop are visible on the left of the picture

Just three months later, in July, Surveyor 4 was not so lucky. After a textbook flight to the Moon, contact was lost with the spacecraft just 2.5 minutes before touchdown in the Sinus Medii (Central Bay) region and it crashed onto the lunar surface. It’s believed that the solid-fuel descent engine may have exploded.

Launched on 8 September, Surveyor 5 also encountered engine problems on descent to the lunar surface, with a leak in the spacecraft's thruster system. Fortunately, it survived to make a safe landing and returned over 20,000 photographs over three lunar days. Instead of a sampler arm, Surveyor 5 carried an alpha backscattering experiment, and had a bar magnet attached to one landing pad. It carried out the first off-Earth soil analysis and made one of the most significant finds of the Surveyor missions — that the Moon's surface is likely basaltic, and therefore suitably safe for human exploration.

Surveyor 5's alpha backscattering experiment, sometimes described as a chemical laboratory on the Moon

Surveyor 6

Surveyor 5's alpha backscattering experiment, sometimes described as a chemical laboratory on the Moon

Surveyor 6 landed safely near the Surveyor 4 crash site in November 1967 carrying an instrument package virtually identical to Surveyor 5. The spacecraft transmitted a total of 30,027 detailed images of the lunar surface, as well as determining the abundance of the chemical elements in the lunar soil. As an additional experiment, Surveyor 6 carried out the first lift-off from the Moon. Its engines were restarted, lifting the probe 12 ft above the lunar surface, and moving it 8 ft to the west, after which it landed again safely, and continued its scientific programme.

Surveyor 7 – a Last Hurrah!

The successful completion of the Surveyor 6 mission accomplished all the goals that NASA had set for the Surveyor programme as an Apollo precursor. The JPL Surveyor team therefore decided that for the final mission they would aim for a riskier landing site, in the rugged highlands near the Tycho Crater. The engineers gave Surveyor 7 a less than 50-50 chance of landing upright due to the rough terrain in the area!

Tycho crater was the challenging landing site for NASA's last Surveyor mission

Tycho crater was the challenging landing site for NASA's last Surveyor mission

Launched on 7 January, Surveyor 7 is the last American robot spacecraft scheduled to land on the Moon before the Apollo astronauts. Its instrument package combines all the experiments used by its predecessors, in order to determine if the rugged terrain would be suitable for a future Apollo landing site.

During its first lunar day, the spacecraft’s camera has returned more than 14,000 images, including some views of the Earth! One of Surveyor 7’s innovations is the use of mirrors to obtain stereoscopic lunar photos. Laser beams directed at the Moon from two sites in the United States have also been recorded by cameras aboard Surveyor 7.

A view of the Earth captured by Surveyor 7's camera

Getting a Scoop

A view of the Earth captured by Surveyor 7's camera

Getting a Scoop

Surveyor 7’s versatile soil mechanics surface sampler is a key instrument on this mission. Designed to pick up lunar surface material, it can move samples around while being photographed, so that the properties of the lunar soil can be determined. It can also dig trenches up to 18 inches into the lunar surface to determine its bearing strength and squeeze lunar rocks or clods. The sampler is a scoop with a container which can be opened or closed by an electric motor. The scoop has a sharpened blade and includes two embedded magnets, to search for ferrous minerals and determine the magnetic characteristics of the lunar soil. So far, the moveable arm and scoop have performed 16 bearing tests, seven trenching tests, and two impact tests.

Only a few Surveyor 7 pictures are currently available, but this view of Surveyor 3 digging a trench into the Moon's surface shows how the scoop carries out this task

Only a few Surveyor 7 pictures are currently available, but this view of Surveyor 3 digging a trench into the Moon's surface shows how the scoop carries out this task

The scoop is mounted below the spacecraft’s the television camera so that it can reach the alpha-scattering instrument in its deployed position and move it to another selected location. In fact, the scoop helped to free the alpha-scattering instrument when it failed to deploy on the lunar surface. It has also been used to shade the alpha-scattering instrument and move it to different positions to evaluation other surface samples. During 36 hours of operation between January 11 and January 23, 1968, the sampler has performed flawlessly. Soil analyses have been conducted, as well as experiments on surface reflectivity and surface electrical properties.

Surveyor 7 is now “sleeping” through its first lunar night. If it survives this period of intense cold, hopefully it will continue to produce significant results during its next lunar day. But if it doesn’t, the scientists and engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory are already describing the Surveyor programme as a “treasure house of information for landing a man on the Moon before the end of this decade”.

This has to be a fitting epitaph for any space mission.

![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 24, 1968] On Track for the Moon (Apollo 5 and Surveyor 7]](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/apollo_5_patch-672x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1967] Strange New Worlds and Staid Old Ones (May 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1967] Vistas near and far (April 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670320cover-672x372.jpg)