by Fiona Moore

February’s rain and sleet freeze the toes right off the feet, as Flanders and Swann once sang. Still, there’s reason to celebrate: the Family Law Reform Act has come into effect, reducing the age of majority from 21 to 18 for most purposes, homosexual sex being a notable exception. Decimalisation continues apace, with the half-crown coin being taken out of circulation (don’t worry, you can exchange it at most banks).

Term has resumed at Royal Holloway College and my students are attacking the writings of Margaret Mead with their usual enthusiasm. However, there is also widespread unease among our Nigerian foreign student community over the capitulation of Biafra: many of them have had no news of their families, and are also concerned about when they will be able to go home. The university is rallying round to make sure everyone is housed, and there are jobs aplenty in Southwest London if they need to stay a while, but it is still an anxious situation for them.

Jubilant street scene in Lagos upon the news of surrender, January 12, 1970

No news of Yoko Ono after December’s festive anti-war campaign. Rumour has it she and her husband have gone off to New York for some reason, so I expect I’ll be covering her activities less often. What all this means for her husband’s band, I’m not sure.

On to New Worlds, which continues its trajectory back to being an SFF magazine, but unfortunately almost every story is suffering from a lack of originality this month.

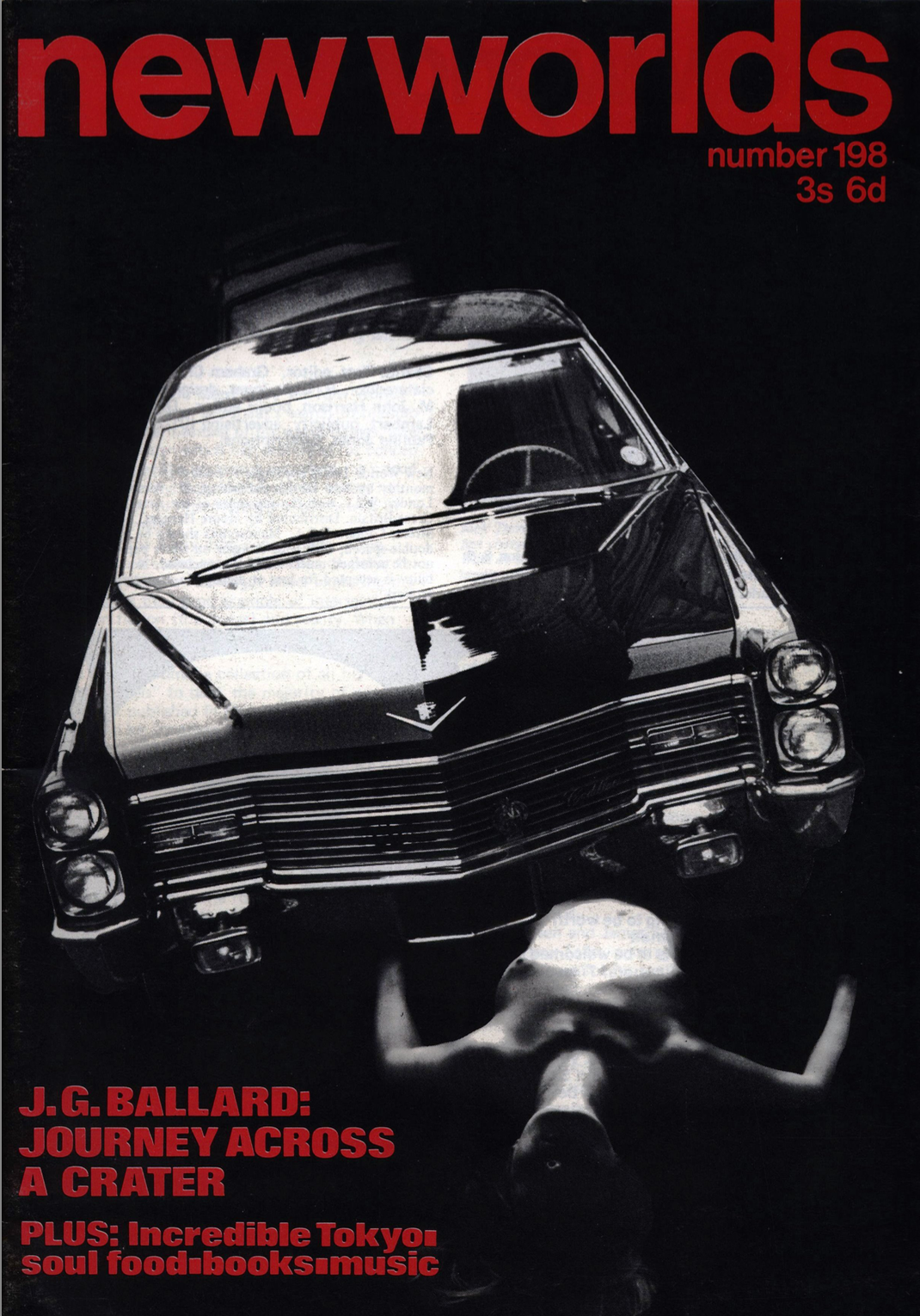

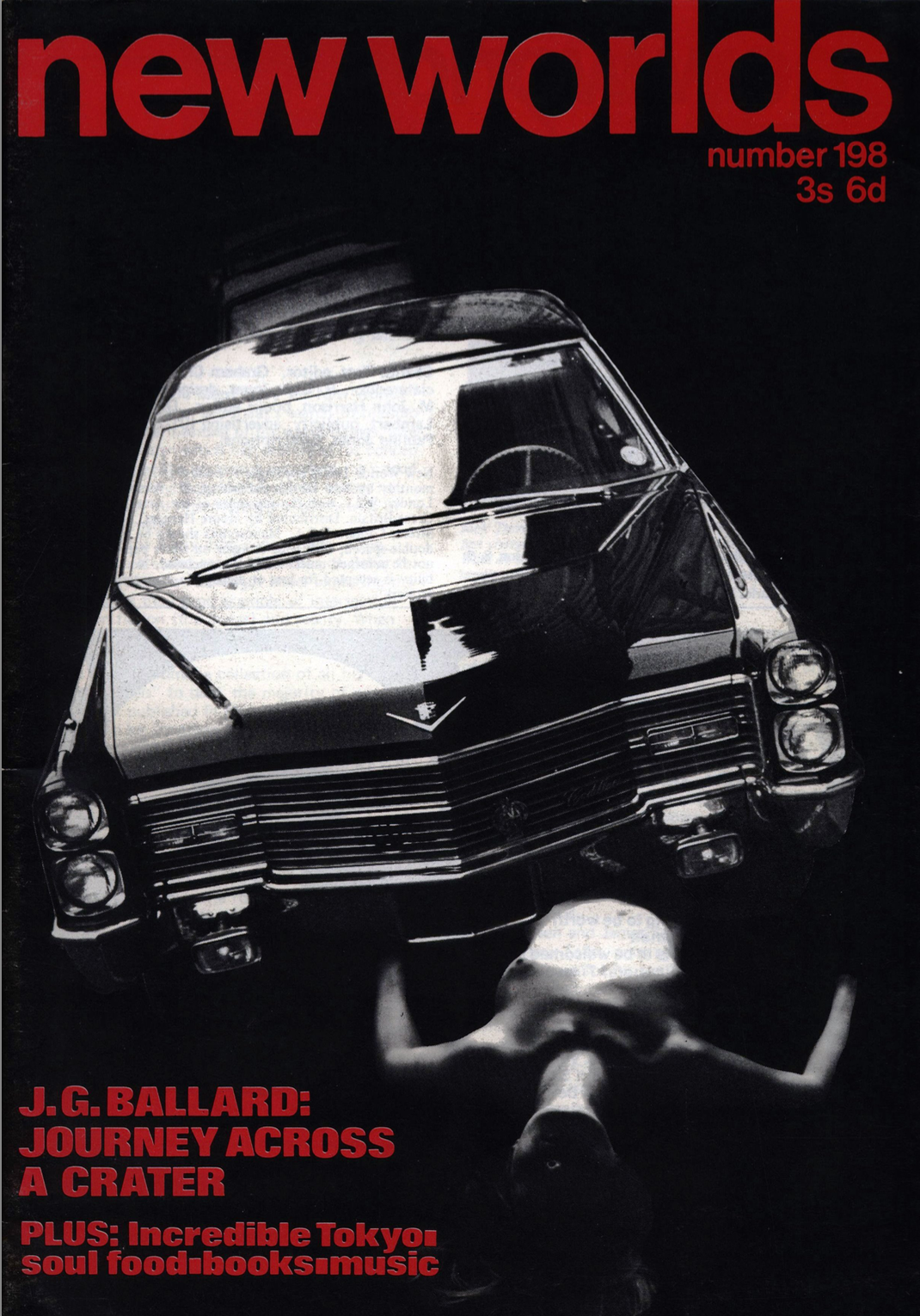

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Lead-In

Mostly introducing new writers and illustrators to the magazine, as well as showcasing the pieces by Ballard and Watson, and drawing the reader’s attention to a new, presumably ongoing, feature of the publication—of which, more later.

Journey Across a Crater by J.G. Ballard

A piece about a crash-landed astronaut finding his way to civilisation. There are resonances with Ballard’s earlier story “You and Me and The Continuum” (Impulse Magazine 1:1, 1966), and also some vivid sexual imagery about car crashes, which makes sense given that the Lead-In tells us Ballard is currently working on a novel about these. Interesting enough as a revisitation of familiar Ballard themes but no new ground broken. Three stars.

Soul Fast by Gwyneth Cravens

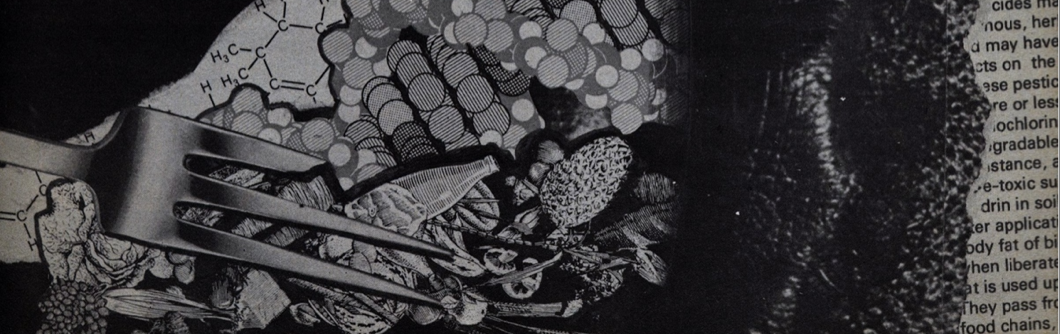

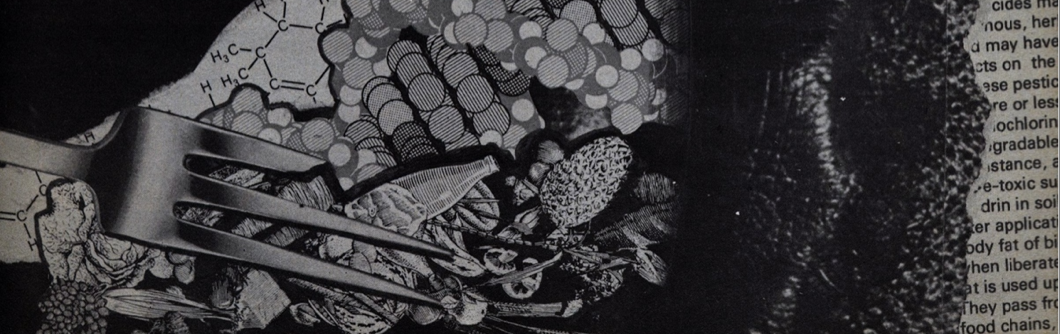

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

A story by a woman in New Worlds is always worth remarking on, particularly a woman who is a current editor of the New Yorker. However, I can’t help but notice that women writers in New Worlds always seem to get pigeonholed into writing about domestic or otherwise nurturing themes. This one, for instance, is about food and the role it plays in relationships. There are some interesting satirical commentaries on race and how over-privileged White Americans with superficial attitudes towards spirituality crib from Black and Asian cultures, which makes it worth checking out. Four stars.

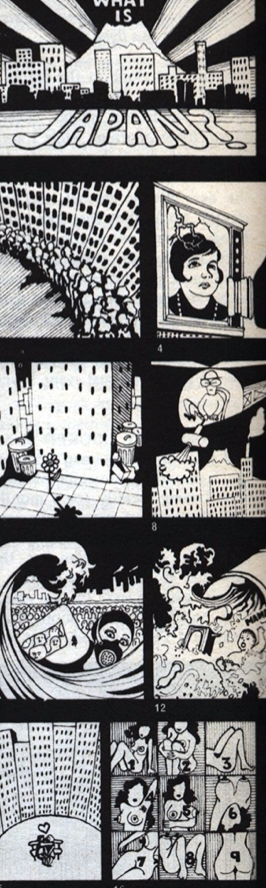

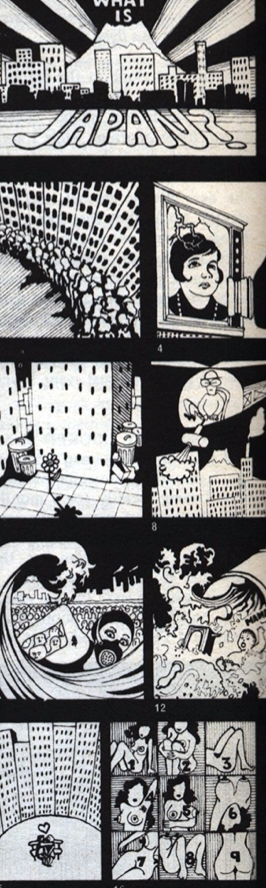

Japan by Ian Watson

Illustration by Judy Watson

This is the standout piece of the issue. Watson, a Tokyo resident, introduces Japan to English readers in a surreal, outré travelogue emphasising the weird SF-ness of living in a country where the atmosphere isn’t breathable, earthquakes and fires are endemic, sexual fetishes are catered to in the mainstream media, and consumerism takes on the status of art. The illustrations are by Watson’s wife Judy. It’s beautifully written, though, having been to Japan once or twice myself, I worry that it’s over-emphasising the strangeness of the country to a point where it might simply confirm Europeans’ stereotype that the East is a bizarre and hostile place. Nonetheless, five stars.

Apocrypha by D.M. Thomas

A poem about the life of Jesus. It’s not terribly original, but I did find it engaging and nicely written. Three stars.

6B 4C DD1 22 by Michael Butterworth

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Another not-terribly-original piece in the vein of “let’s drop acid and describe the resulting trip as an SFF story.” The mind-altered protagonist lurches back and forth between several different realities, some more surreal than others, with recurring characters playing different roles. I like Butterworth’s way with prose, and some of the metaphors and descriptions are genuinely arresting, but I’d like to declare a moratorium on anyone using Alice in Wonderland as an acid trip metaphor; it’s been done to death. Similarly, while I really like the accompanying art, it looks exactly the same as every other set of illustrations intended to show an acid trip (see above). Four stars.

A Spot in the Oxidised Desert by Paul Green

Illustration by John Bayley

Illustration by John Bayley

A short prose poem from the point of view of a dying sentient tank in a future desert battlefield. Possibly the most innovative piece this issue. Four stars.

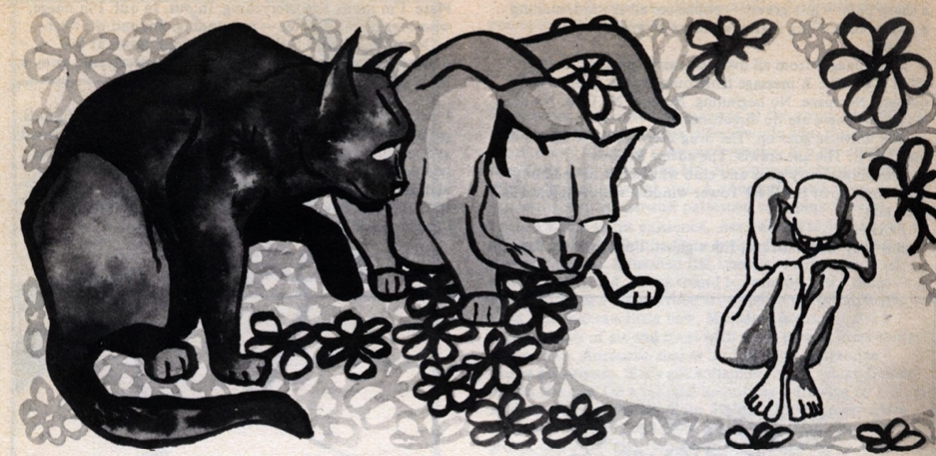

The Bait Principle by M John Harrison

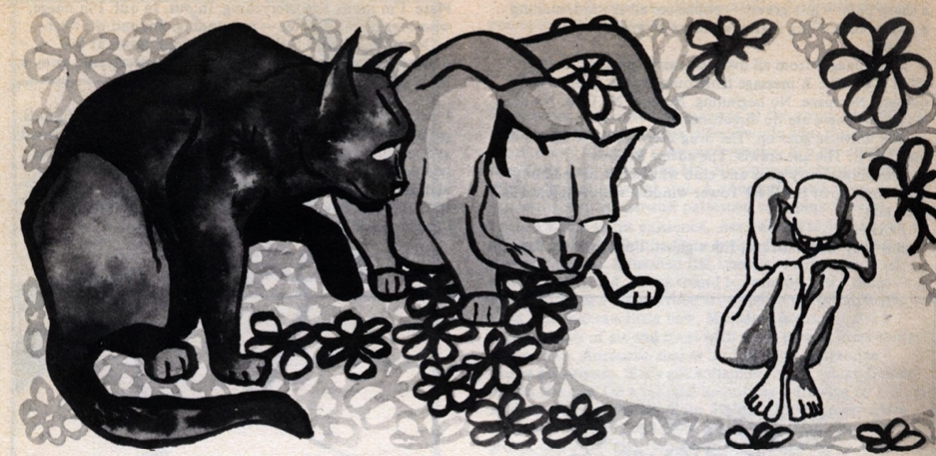

Illustration by Ivor Latto

Illustration by Ivor Latto

Patients in an asylum begin to share each other’s delusions, and, in doing so, bring them into reality, leading to an ailurophobe being tormented by human-sized cats. This is an amusing twist on the familiar crazy-people-are-actually-seeing-the-truth genre, but at the end of the day that’s all it is. Two stars.

The Wind in the Snottygobble Tree: Conclusion by Jack Trevor Story

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Finally this serial lurches to an end, with some heavy-handed satire about the Catholic and Scientologist churches, spies and the police. I have the feeling that the story-so-far summary is in fact retroactively adding elements, but I’m not interested enough to go back and find out. The eponymous tree finally appears (it's a species of yew, apparently), but I don’t think it’s got much to do with the story apart from being a bit gross. One star.

A Vid by James Sallis

A short poem which didn’t really do much for me. Two stars.

Books

By Mike Walters, John T. Sladek and Douglas Hill. There’s a delightfully excruciating pun on the first page, although Walters has to contort his review in order to fit it.

Music

As regards the new feature I mentioned above: New Worlds now has a music column! This is certainly a welcome innovation, and I look forward to seeing whether the New Wave has a particularly distinctive take on album reviews.

Overall, I’d say the magazine is suffering this month from a lack of originality. Everything is competently written at worst and sometimes really beautiful, but most of it is things that have been done before. Even the music column is something we see over and over in other magazines, and whether the fact that the reviewers are from the usual New Worlds crowd will make a difference is uncertain.

Is the New Wave played out? Can it (and Mr. Yoko Ono’s musical career) survive into the new decade? Time will tell.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Follow on BlueSky

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

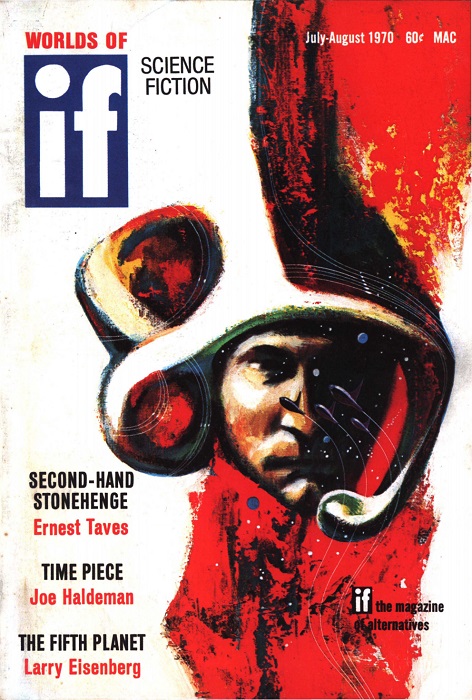

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[April 6, 1970] Uncovered (May 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/amz-0570-cover-672x372.png)

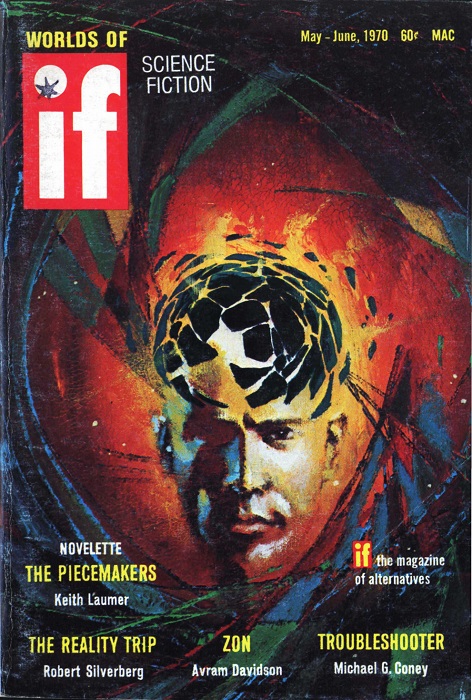

![[April 2, 1970] Being Human (May-June 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IF-1970-05-Cover-472x372.jpg)

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

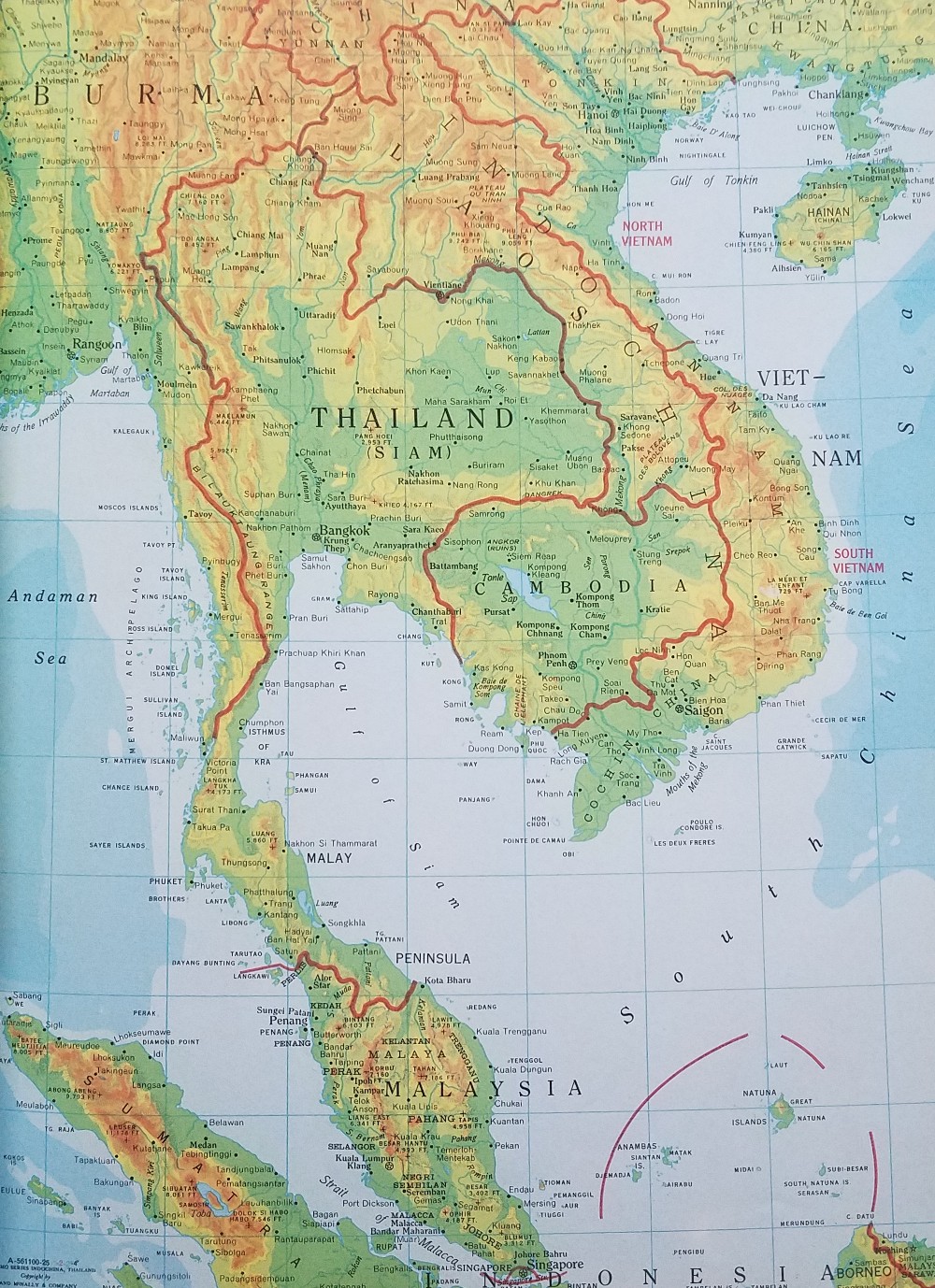

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol. Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

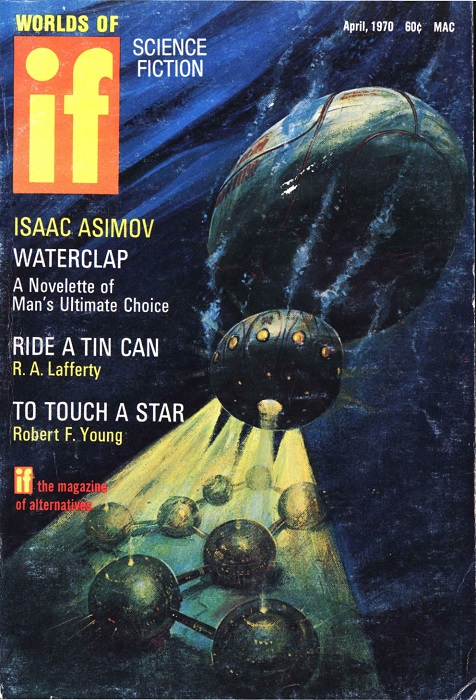

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan![[March 2, 1970] Par for the course (April 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IF-1970-04-Cover-476x372.jpg)

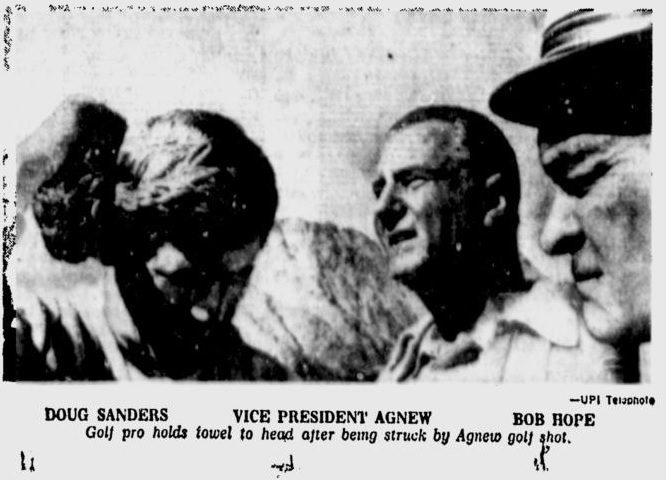

Wire photo of the aftermath.

Wire photo of the aftermath. Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan![[February 12, 1970] Up Front (March 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/amz-0370-cover-672x372.png)

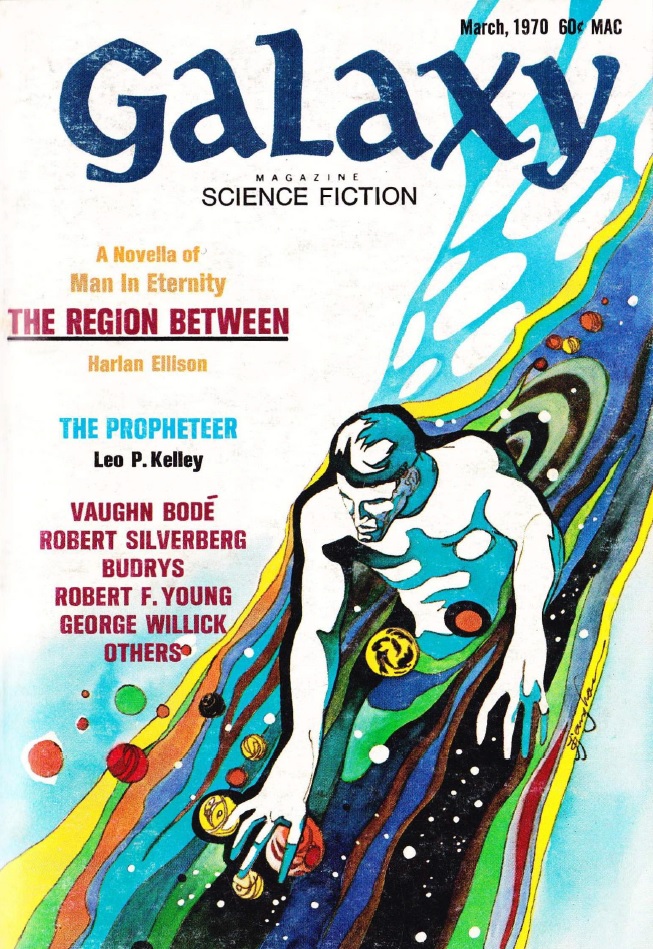

![[February 8, 1970] Boldly going to the Region Between (March 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700208galaxycover-653x372.jpg)

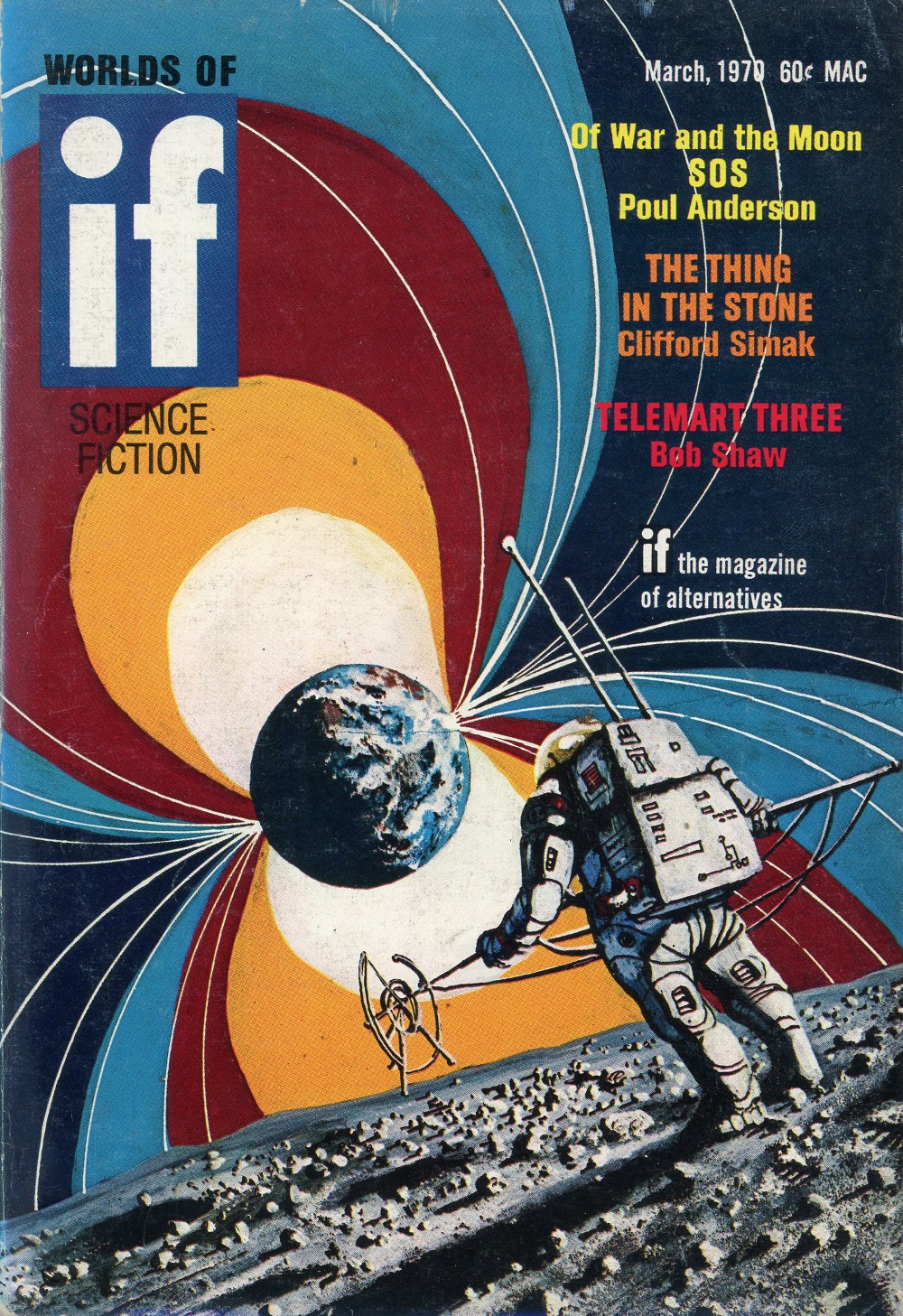

![[February 2, 1970] Deceptive Appearances (March 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IF-1970-03-Cover-479x372.jpg)

The arbiter, an NCR 315.

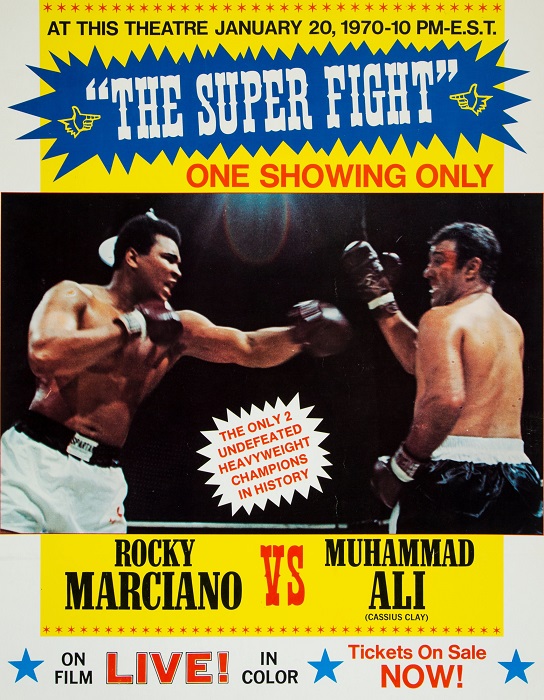

The arbiter, an NCR 315. Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about.

Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about. Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.

Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.![[January 22, 1970] Sergeant Pepper's New Wave Writers' Club Band: New Worlds, February 1970](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NW_2_70_cover-672x372.png)

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Cover by Roy Cornwall

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration, artist uncredited (possibly Charles Platt)

Illustration by Alan Stephanson

Illustration by Alan Stephanson Illustration by John Bayley

Illustration by John Bayley Illustration by Ivor Latto

Illustration by Ivor Latto Illustration by Roy Cornwall

Illustration by Roy Cornwall

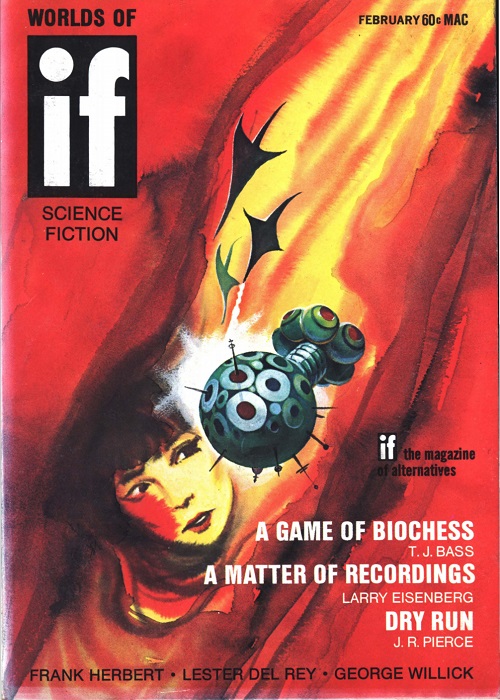

![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)

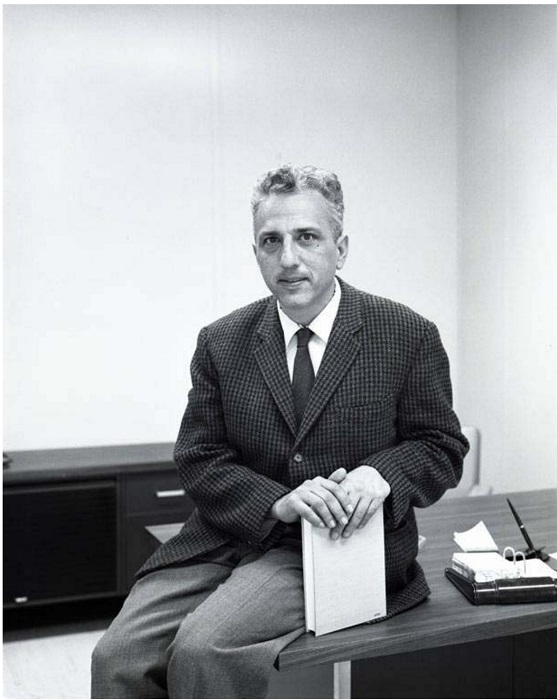

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

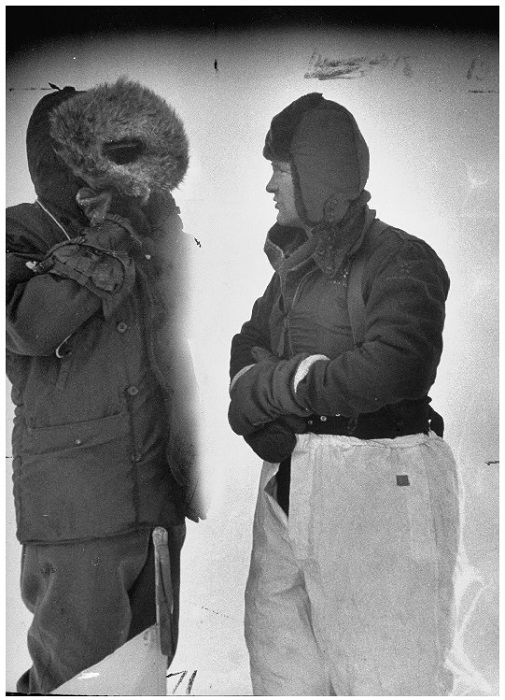

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

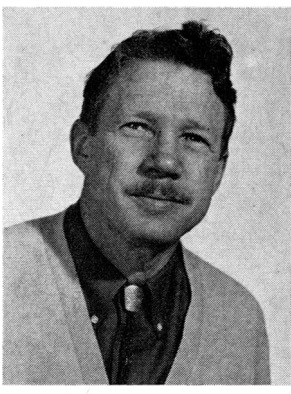

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find. Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.