by Victoria Silverwolf

Printers' Devils

When I'm reading a book or magazine, if I come across a mistake in printing it takes me right out of the story. If it's a simple misspelling, it's no big deal, yet there's still that brief moment when my mind unwillingly goes back to reality.

More serious problems, such as a few lines duplicated or in the wrong place, cause greater distress. In the most extreme cases, as when entire pages are missing, the experience is ruined.

I bring this up because my copy of the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow contains an egregious example of this kind of technical shortcoming.

Dig That Crazy, Mixed-Up 'Zine, Man

Cover art by Gray Morrow.

Allow me to provide you with a metaphorical road map for the route you need to take between the front and back covers of the publication.

Pages 1 through 15: OK so far.

Pages 18 through 21: Hey, what happened to the other two?

Pages 16 through 17: Oh, there they are.

Pages 22 through 45: Smooth sailing.

Pages 48 through 55: Here we go again!

Pages 46 through 47: Another two pages out of place.

Pages 56 through 164: No more detours, thank goodness.

If I've managed to annoy and confuse you with that, now you know how I felt when I read this issue. The short, sharp shock (to steal a phrase from Gilbert and Sullivan's The Mikado) of jumping from an incomplete sentence on page 15 or page 45 to a completely unrelated incomplete sentence on page 18 or page 48, then having to flip through the magazine to find page 16 or page 46, then having to hop back to page 15 or page 45 to remember what the incomplete sentence said, was a pain in the neck. (That's another allusion to the short, sharp shock. Ask your local G and S fan what it means.)

Thus, if I seem a little more critical than usual, blame it on the printer (not on the Bossa Nova.) With that in mind, let's get started.

The Ultra Man, by A. E. Van Vogt

Illustrations by Peter Lutjens.

I'll confess that I have a real blind spot when it comes to Van Vogt. I know he's one of the giants, like Asimov and Heinlein, of Astounding's Golden Age, but I almost always find his stuff hard going. Often I can't follow the plot at all. When I think I understand what's going on, it usually seems overly complicated. Given my prejudice, I'll try to be as objective as possible.

The setting is an international lunar base. A psychologist demonstrates his newly acquired psychic ability to a military type. It seems the headshrinker can tell what somebody is thinking by looking at his or her face. Suddenly, he spots an alien disguised as an African who intends to kill him.

(There's an odd explanation for why the alien takes the form of an African. Something about that would give him the protection of race tension. I have no idea what that's supposed to mean. That's my typical reaction to Van Vogt.)

We soon find out that other folks have been gaining psychic abilities, all of them following a very strange pattern. The people retain the power for a couple of days, then lose it for a while, then get it back in a much more powerful form for a brief time. If there was any sort of explanation for this bizarre phenomenon, I missed it.

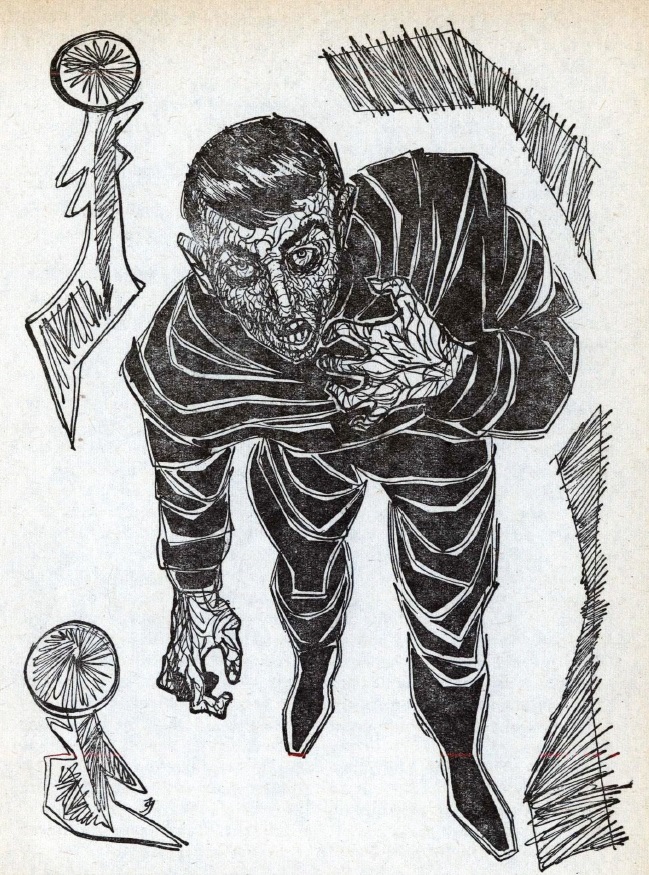

Like the first illustration, this is more abstract than representative.

Anyway, the psychologist and the military guy get involved with a Soviet psychiatrist and with aliens intent on conquering humanity. Only the psychologist's intensified psychic powers, of a very mystical kind, save the day.

Science fiction is often accused of being a literature full of power fantasies, and this story could serve as Exhibit A. (Just look at the title.) The psychologist's abilities eventually become truly god-like.

I have to admit that this thing moves at an incredibly fast pace. It reads like a novel boiled down to a novelette. I can't call it boring, at least, even if it never really held together for me.

Two stars.

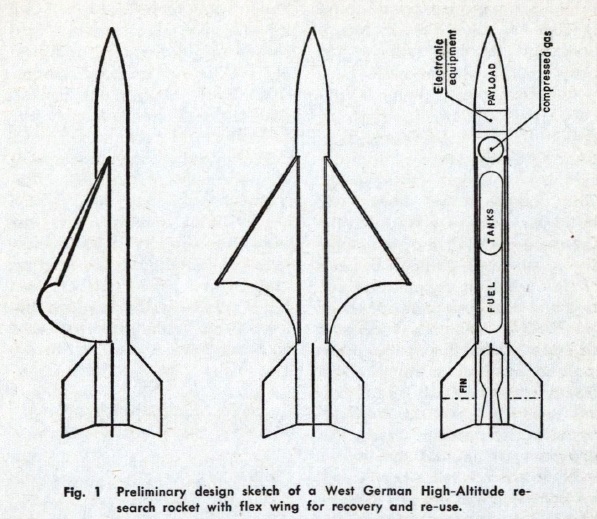

The Willy Ley Story, by Sam Moskowitz

Uncredited photograph.

The tireless historian of science fiction turns his attention to the noted rocket enthusiast, science writer, and SF fan. As usual for Moskowitz, there's a ton of detail, as well as a seemingly endless list of early publications by Ley and others. For an encyclopedia article, it would be a model of thoroughness. As a biographical sketch for the interested reader of Ley's writings, it's pretty dry stuff.

Two stars.

Spy Rampant on Brown Shield, by Perry Vreeland

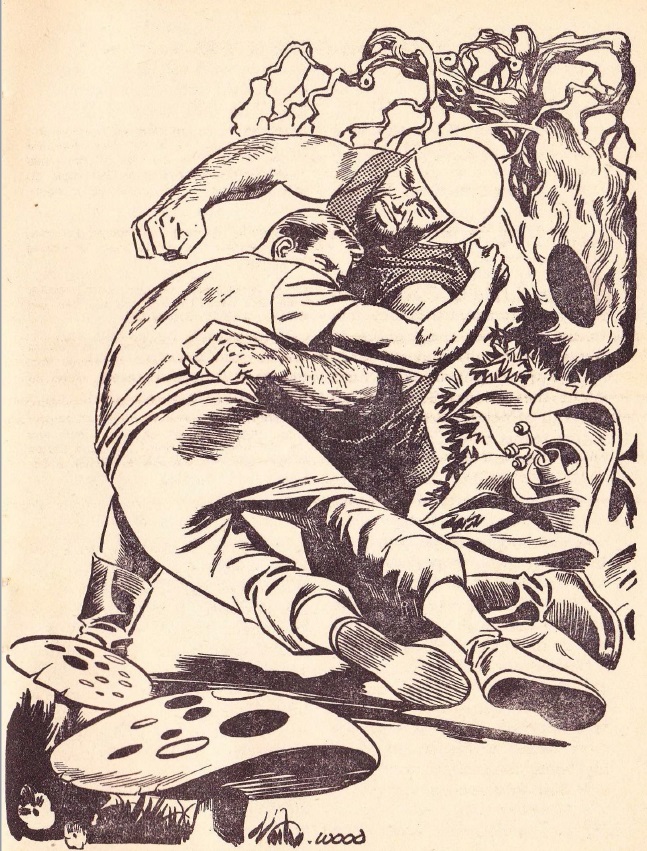

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

A writer completely unknown to me jumps on the James Bond bandwagon with this futuristic spy thriller.

It seems that the Cold War has been replaced by a struggle between the good old USA and some kind of unified Latin America. The enemy Browns — named for their uniforms, I believe, and not intended, I hope, as a reference to their ethnicity — have a shield that will protect them from nuclear weapons. This means that the dastardly fellows can attack the Norteamericanos with impunity.

The protagonist is the typical highly competent secret agent found in this kind of story, although said to be more cautious than others. He gets a cloak of invisibility so he can sneak into the office of the Brown scientist in charge of the shield and get the plans for it.

Our hero stuns his target.

The invisibility gizmo has several limitations. Dirt and moisture render it less than effective in hiding the user. (In an amusing touch, the hero has to keep changing his socks.) Some kind of scientific mumbo-jumbo is used to explain why it shimmers when more than one source of light, of particular intensities and locations, strike it.

Much of the story consists of the spy just waiting, so he can walk through a doorway, opened by somebody else, without drawing attention. In an interesting subplot, he has to fight altitude sickness as well, because the headquarters of the scientist are located at a great elevation, way up in the Andes.

Walking through the streets of La Paz, the highest capital city in the world.

The twist ending, during which we find out the true nature of the Browns' shield technology, is something of a letdown. It also allows the hero to escape from the Bad Guys, thanks to dumb luck and pseudoscience.

Two stars.

The Worlds That Were, by Keith Roberts

Here's a rare American appearance by a new but quite prolific British author. The narrator and his brother, from an early age, have been able to escape the slum in which they live and enter other times and places. He meets a woman in a dreary public park and brings her home. This leads to a battle with his brother, who sabotages the paradises into which he brings the woman, even trying to kill her. At the end, the narrator learns the truth about his brother and the power they share.

This is a delicate, emotional, poetic tale, full of vivid descriptions of both the beautiful and the ugly. Despite the speculative content, in essence it is a love story. Notably, the narrator, despite his incredible ability, is quite ordinary in most ways. Similarly, the woman isn't an alluring beauty or a temptress, but a fully believable, realistic character. This makes their romance even more meaningful.

Five stars.

Delivery Tube, by Joseph P. Martino

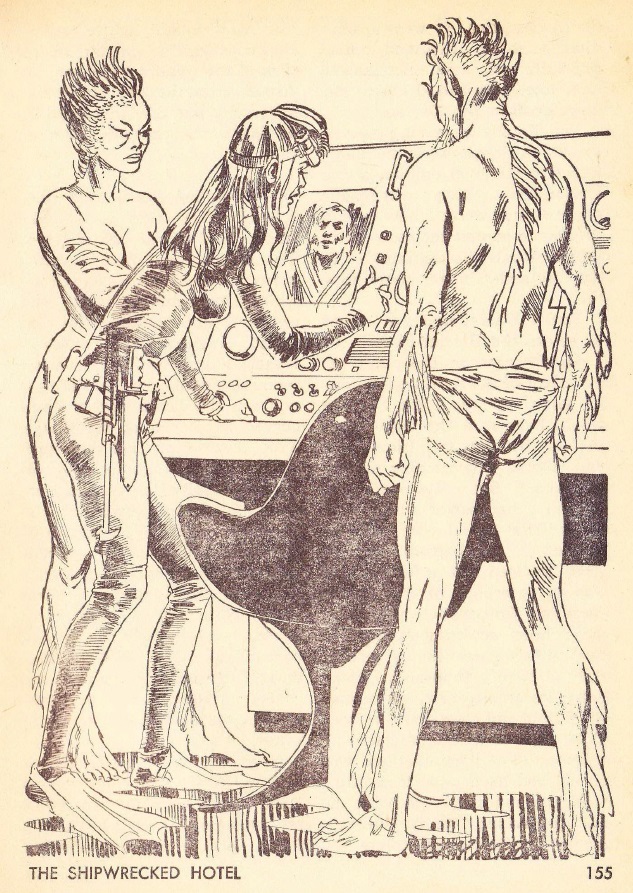

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

More proof of the continuing effect on popular culture of the late Ian Fleming, if any be needed, appears in yet another spy yarn. The setting is the fictional Republic of Micronesia. (Given the fact that we're told this is one of the most populous nations on Earth, which is hardly true for the many tiny islands collectively known as Micronesia, I'm guessing this is supposed to be something like Indonesia.)

Anyway, the supposedly neutral Micronesians, with help from Red China, possess atomic bombs and at least one satellite to send into orbit. The paradox is that they don't seem to have any way to launch either the bombs or the satellite. Our hero, with the help of some local opposition parties and anti-Communist Chinese, investigates the mysterious construction project happening on Micronesia's main island.

What are they building in there?

Along the way, he gets mixed up with an old enemy, a Soviet agent. The USSR wants to find out what Micronesia is up to as well, so the two foes become temporary allies. A lot of familiar spy stuff goes on. I'm pretty sure you'll figure out what the construction is all about long before the hero does.

Two stars.

Alien Arithmetic, by Robert M. W. Dixon

People who hate math can skip this part of my review.

The author considers various ways to record numbers, other than our familiar base ten Arabic numerals. Before he gets to the alien stuff, he talks about Roman numerals, and demonstrates how to perform addition with them. It makes you glad you don't use them in daily life.

After a brief discussion of binary arithmetic, familiar to many of us in this modern age of electronic computers, we get to some weirder ways of symbolizing numbers.

First comes an odd and confusing system in which the column on the right uses only 0 and 1, the one to the left of that 0, 1, and 2, the one to the left of that 0, 1, 2, and 3, and so forth. As an example, 4021 translates as (4x1x2x3x4) + (0x1x2x3) + (2x1x2) + (1×1) = (96) + (0) + (4) + (1) = 101. (The author claims it translates to 99, but I'm just following his exact method of calculation, using the same example and the same steps. Somebody doublecheck me, but I think I'm right! For 99, I think the number would be 4011.)

Next we turn to a way of recording numbers by combining symbols for their prime factors. This is easier to explain via the author's diagram than in words.

An example of number symbols based on prime factors. The symbol for six combines the symbols for two and three, and so forth.

These imaginary number systems seem awfully impractical to me. The author vaguely links them to imaginary aliens, but that's really irrelevant. My formal education in mathematics ended with first semester calculus, so I'm no expert, but this kind of thing interests me to some extent (which is why this part of the review is longer than it should be.)

Number-haters can start reading again.

Two stars.

Trees Like Torches, by C. C. MacApp

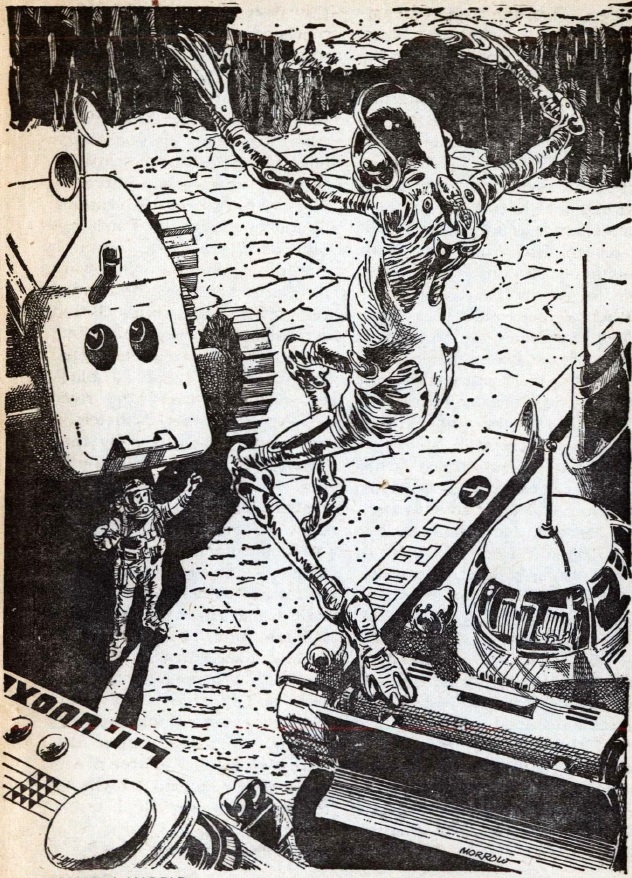

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

We jump right into a drastically changed far future Earth, so it takes a while to figure out what's going on. Many centuries before the story begins, aliens conquered the planet. It's considered an unimportant, backwater world, so they use it as a hunting preserve. (I'm assuming this includes humans as prey, although this isn't made explicit.) They also mutated Earth creatures into new forms, so the surviving humans have to face dangerous animals.

As if that weren't enough to ruin your day, there are also human renegades who kidnap children, for a purpose not revealed until the end. The plot deals with a man out to rescue his daughter from the renegades. Help comes from blue-skinned, telepathic human mutants.

Beware the trees!

A lot of stuff goes on besides what I've noted above. Despite the science fiction explanation for everything, this fast-paced adventure story felt like a fantasy epic to me. The beings in it seem more magical than biological. It's not a bad tale, if a little hard to get into.

Three stars.

Holy Quarrel, by Philip K. Dick

Illustrations by Dan Adkins.

Three government agents wake up a computer repairman. It seems that the super-computer that monitors all the data in the world for possible threats against the United States has a problem. It claims that it needs to launch nuclear weapons against a region of Northern California. The G-men managed to stop that by jamming a screwdriver into the machine's tapes.

The danger, or so it says, comes from a fellow who manufactures gumball machines. This seems utterly ridiculous, of course, so the government guys want the repairman to figure out what's wrong with the computer. Just to be on the safe side, they investigate the gumball magnate, and study the candy machines as well as the stuff they contain. They communicate with the stubborn computer, even trying to convince it that it doesn't really exist.

You don't really think it will fall for that, do you?

You can tell that there's more than a touch of the absurd to the plot, along with a satiric edge. The author throws in the computer's religious beliefs, as well as an outrageous ending. The whole thing has the feeling of dark comedy. (There are references to the USA having attacked both France and Israel, due to the computer's perception of threats.) Like a lot of works by this author, it has a plot that seems improvised. It always held my interest, anyway.

Three stars.

In Need of Some Repair

So, were the works in this issue as messed up as the page numbers? For the most part, I have to admit they were. With the shining exception of an excellent story from Keith Roberts, both the fiction and articles were disappointing, although they got a little better near the end of the magazine. My sources in the publishing world tell me that this will be the last bimonthly issue of Worlds of Tomorrow, and that it will turn into a quarterly. This should give the editor, and the printer, time to deal with its problems.

Even an amusement park has to close down once in a while to fix things.

The Journey is once again up for a Best Fanzine Hugo nomination — and its founder is up for several other awards as well! If you've got a Worldcon membership, or if you just want to see what Gideon's done that's Hugo-worthy, please read his Hugo Eligibility article! Thank you for your continued support.

![[March 14, 1966] Random Numbers (May 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n07_1966-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

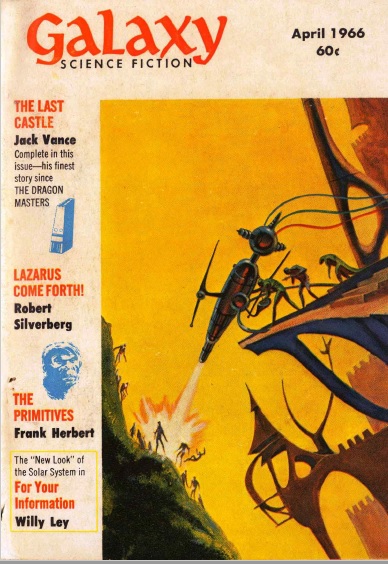

![[March 10, 1966] Top Heavy (April 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660310cover-388x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1965] Saving the worst for first (August 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650708cover-521x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)

![[November 15, 1964] Veteran's Triumph (December 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641115cover-432x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1964] Rough Patch (June 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640508cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1964] A Taste of Homely (February 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640108cover-570x372.jpg)