by Gideon Marcus

Nostalgia

Stop me if you've heard this one before ("Stop! Stop!") but when I picked up that first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine in October 1950, I was hooked. I had encountered SF previously, as a kid with Edgar Rice Burroughs, H. G. Wells, and Jules Verne. I'd devoured L. Frank Baum's works. And through the 30s and 40s, I leafed through the odd issue of Astounding. But it wasn't until I read H. L. Gold's mag that SF really seduced me. Here were mature stories for adults going beyond the "gimmick" story.

In 1954, I became voracious, buying every mag in sight. Some were worthy, like Fantasy and Science Fiction, Satellite, Beyond and (often) Astounding and Fantastic Universe. Others were…less than worthy: Amazing, Infinity, Imagination, Super Science, and on and on. But I read them all. I was hooked.

Gold left the editorship in 1961, and the esteemed Fred Pohl took over. The magazine has been in a bit of a holding pattern since the turn of the decade, rarely being outright bad, but rarely evoking the heights of those first few years of publication, when virtually every story was a stunner.

The latest issue is a stunning return to form.

The Issue at Hand

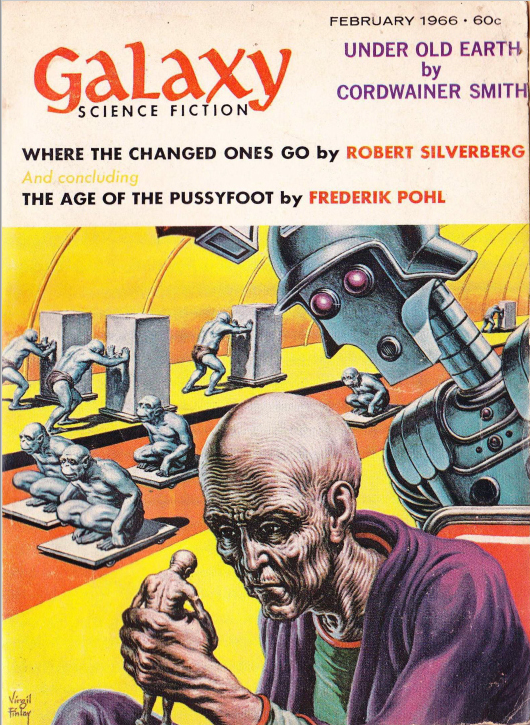

by Virgil Finlay

Under Old Earth, by Cordwainer Smith

The enigmatic Mr. Smith has been a staple of Galaxy from early days, and I understand he is one of the folks Mr. Pohl regularly visits to obtain new stories. Under Old Earth is the latest installment in the Instrumentality series, portraying a happy, fatuous humanity atop a slave class of altered beasts and robots.

In this particular story, Sto-Odin, a dying Lord of the Instrumentality heads to the Gebiet, the vast underworld separate from the laws and enforced happiness of the surface world. There, he expects to find the vital spark of humanity that can restore the race. He encounters a self-styled Sun-God who has purloined a piece of the congohelion, a vast structure that regulates the output of stars, to make inhumanly powerful music. And tending his altar is Santuna, dismayed with what the Sun-God has become, and destined for a great role in the eventual Rediscovery of Man.

As always, it is lyrical and lovely, different from anything else you'll ever read. Four stars.

by Virgil Finlay

Courting Time, by Tom Purdom

The excellence continues with this marvelous treatment of polygamy in the mid-21st century on the eve of a great world fair: A composer in love with a woman comprising one eighth of an 8-way marriage wishes to become the next spouse in the cluster. But he has strong competition in the form of a ruthless and irresistable playboy. What's a lovelorn fellow to do?

Tom happens to be a friend of mine, and here are his notes on the genesis of this tale:

I got the idea several years before I wrote the story, when one of the older women in the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society told me she thought every woman needed four husbands, each one good at a different specialty–making money, romance, companionship, parenting. I felt that would work for men, too.

Most stories about group marriage that I'd read, it seemed to me, were stories about group sex. Courting Time is about the sociology of marriage. It owes something to Morton Hunt's The Natural History of Love, a book about the history of Western ideas about sex and marriage. Hunt concludes that our modern vision of marriage essentially demands that a two person relationship fulfill all the needs people once satisfied with their relationships with larger groupings like the extended family. You're supposed to find one person who can be your business partner, sexual partner, romantic partner, parent to your children, and lifelong companion. No single individual can do a five star job in all those roles.

I really liked the idea of the global world's fair. The world fair in New York was going on at that time and I asked myself what a world fair might look like in the future.

I called the story "Courting". I like one word titles. Fred Pohl changed it to "Courting Time", querying my approval, which has more of a lilt.

Other than Heinlein's The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Courting Time is the only SF story dealing with polygamy I've read in recent history. It's a very good story, though it could use a little more development with the protagonist's falling in love with each of the spouses. Tom agrees with my four star assessment.

Read it!

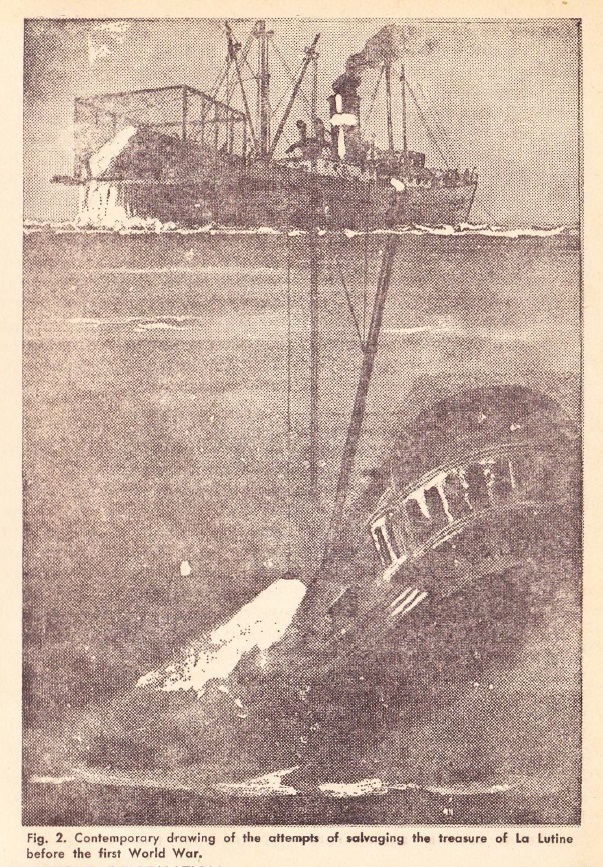

For Your Information: The Wreck of La Lutine, by Willy Ley

160 years ago, the gold ship, La Lutine, was capsized in a storm off the coast of Holland. Since then, numerous attempts of increasing sophistication have been made to recover the lost bullion, with limited success. Ley's account of these efforts is fascinating — maybe the Journey should put together a recovery mission of its own!

Four stars.

The Echo of Wrath , by Thomas M. Disch

Little Ilisveta, an eight year old Martian, is bored with her rough frontier life and yearns for something better, something like the Earth-trotting days her grandfather Dmitri and grandmother Sally enjoyed some sixty years prior. But such a life can never be.

Echo is a relatively unremarkable story until the end, which struck me in the gut with the force of a train. You've done it again, Mr. Disch.

Four stars.

Where the Changed Ones Go, by Robert Silverberg

by Jack Gaughan

Just last issue, Robert Silverberg gave us the second in a series one might call Blue Fire, a collection of loosely related novellas set in a future where the secular scientific religion of Vorsterianism has achieved currency across the Earth.

But not across the planets. The aloof Martians and the arrogant Venusians will have no truck with the Vorsterians. However, for some reason, the heretical Harmonists have managed to get a foothold on the hostile second planet from the Sun. So Nicholas Martell, a Vorsterian minister from Earth discovers when he runs across Brother Mondschein (who we met in the last story), who warns Martell that his errand is futile.

Martell, who has undergone a massive physical alteration just to live on Venus, will not be easily deterred — especially as he seems to have found his first potential convert, a young boy with the power of telekinesis.

Silverberg's Venus might as well be a random alien world, so little resemblance does it bear to the actual Venus. Astronomical quibbles aside, however, it's a fine story.

Four stars.

Eye of an Octopus, by Larry Niven

The first expedition to Mars finds Martians, and they're far more like (and unlike!) humans than they could have imagined. Is the well they discover for drinking or something else?

A well-drawn little puzzle story. We've taken to reading Niven stories, when they come out, at bedtime. Janice appreciated the wealth of detail briefly described and gave it four stars. Lorelei was less thrilled, giving it a solid three.

I'd split the difference if I could, but it's not a novel, so I can't. I'd say it's a worthy three star tale.

In the Imagicon, by George H. Smith

What do you give to the man who has everything? Why, nothing of course. A whole lot of it.

And vice versa.

Smith is a fellow who used to write for the lesser mags back in the 50s. He's been AWOL pretty much since I started the Journey so, until I did some digging, I thought he was a new author rather than a veteran.

Anyway, Imagicon is a pretty obvious tale. Not bad, just primitive by Galaxy's standards. I wavered between two and three stars, but just as suspots are pale in comparison to their surroundings despite their great heat, so Imagicon suffers for being in the company of so many good stories.

Two stars.

Mulligan, Come Home!, by Allen Kim Lang

Okay, Imagicon does have the virtue of being next to the only dud story in the issue. Lang's tale is about a fix-it man dispatched by the government to find the elusive trickster and malcontent Mulligan Mondrian. Along the way, we get Mondrian's full life history, detailing his start as a two-bit con man and womanizer and onward to his culmination as a larger-than-life, interplanetary con man and womanizer.

Some cute turns of phrase, but the story collapses under the weight of its own attempted cleverness.

Two stars.

The Age of the Pussyfoot (Part 3 of 3), by Frederik Pohl

by Wallace Wood

At last, we come to the thrilling conclusion of The Age of the Pussyfoot, the misadventures of a 20th Century man unfrozen after death in a 26th Century utopia. When last we left Chuck Forrester, he had not only been fired by his alien employer, he had unwittingly been an accomplice to the alien's escape from Earth. But when the Sirian left, presumably to return at the head of an invasion, he left the penniless Forrester nearly $100 million.

But profound wealth does little to assuage the guilt of the man out of time, especially when he is abandoned by all his newfound friends and his romantic partner. Is he the lynchpin to humanity's salvation or its ruin?

A sparkling, farcical story, just serious enough to keep your attention, Pussycat reads like a Sheckley short story at novel length (Pohl succeeds here where Sheckley, himself, usually can't quite make long pieces work).

That said, it's a little too sketchy and silly to merit four stars. Call it three and a half — worth reading, but probably not good enough to clinch a Galactic Star this year.

Summing Up

What a good issue this was! 3.4 stars is nothing to sneeze at. In fact, it might well end up being the best mag of the month, though we still have five more titles to review. If you're a long time Galaxy reader, enjoy this breath of fresh air. And if you're new to Galaxy, perhaps this issue will tempt you into a subscription, just as that first issue did for me more than fifteen years ago…

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1965] The Face is Familiar (October 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650914cover-551x372.jpg)