by Gideon Marcus

Real-life Adventures

Out in the southeast corner of California is a hidden treasure, a beautiful national park known as Joshua Tree, named for the surreal plants that characterize the region. And in the heart of a tiny, unincorporated community there, resides the place called Space Cowboy Books.

Jean-Paul Garnier, the Space Cowboy, invited us out to see the spring bloom in the wilderness. We were able to take him up on his offer too late to see the flowers, but we did see some amazing petroglyphs and water/wind eroded facades. Even better was the absolute quiet of the place, the aural equivalent of a dark sky (which they also have there).

Of course, it was a several hour trip up Highway 395, over Highway 60 to Interstate 10, and then up Highway 62, which terminates at Joshua Tree.

But we had beautiful scenery, each other for conversation, and a brand new 8-track player in the car for music.

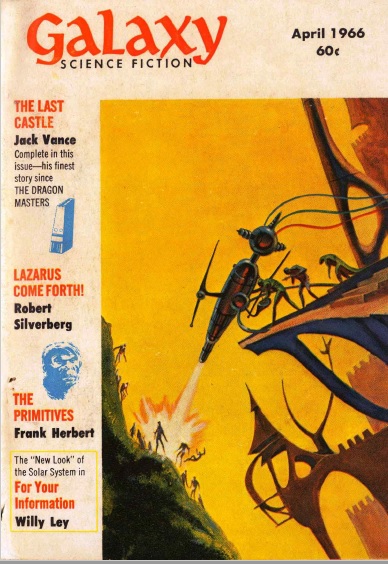

I also had the newest issue of Galaxy, which I was able to read while the Young Traveler drove. Ah, the luxury of having children!

And so, a tour of the trips I went on while on a trip:

Fictional Adventures

by Gray Morrow

Heisenberg's Eyes (Part 1 of 2), by Frank Herbert

by Dan Adkins

Frank Herbert is back. Hooray.

Actually, the setup's not too bad: It's the far future, and humanity has complete control of its genetic destiny. Society is divided between the dronish "Sterries" (sterile humans), the occasional persons who can have potentially viable offspring, and the immortal (but also sterile) Optimen, who run everything, a triumverate's administration lasting a century.

Children cannot be borne the natural way; for an embryo to make it to maturity, a doctor's intervention is required. So begins Eyes, on the eve of a "cutting" that will turn the artificially united progeny of a Mr. and Mrs. Durant into a human being — perhaps even an Optiman.

But before the horrified gaze of the assigned surgeon, some external force modifies the fertilized ovum, making the modification to immortal perfection impossible. An expert is called in, who salvages the embryo, but in the process causes it to become that rarest of beasts: a nascent human that can reproduce on its own. Such a thing is strictly forbidden, yet the expert and his accomplice nurse take pains to ensure that the contraband embryo's nature is hidden from the world. Or so they think.

This takes up about half of this installment, and so a quarter of the book. I have to give credit to Herbert's ability to spew a half dozen pages of medical jargon and keep it interesting.

Things slow down in the second half, when we meet the ruling trio and discover that the plot has wheels within wheels. It also involves an underground race of Cyborgs, who have been biding their time for tens of thousands of years to regain ascendancy over the planet, though they are as clueless about how the modification of the Durant's child occurred as everyone else. Part 1 ends with the first shots being fired in a renewed war between the Optimen culture and the Cyborgs.

A couple of issues: Eyes is written in typical Herbertian style, which is to say in this weird third person omniscient viewpoint that switches characters every sentence and overuses italicized depiction of internal monologues. Perhaps, as one of the oligarchs states in Eyes, "Efficiency is the opposite of Craftsmanship," but I still think the story could have been a lot better at half the length in the hands of someone else. Like Dune. Also, no society remains static for tens of thousands of years — not Egypt and not the weird world of Eyes. And then, of course, there's the pseudo-telepathy the Durants enjoy that involves a code of finger presses. It reminds me of shows where a paragraph of Morse code can be deduced from four dots and a dash.

Anyway, three stars for now. Herbert's done worse, and I've yet to see him do much better.

Priceless Possession, by Arthur Porges

In the depths of space, the 23rd Century equivalent of the ambergris-bearing whale is the anenome-like "Star Sailor" or "S-2." Its micron thin sail, produced over thousands of years, is the most valuable commodity in the universe. On board a particular merchant ship, an Ensign and a Lieutenant find their cupiditous designs hindered by a captain who believes he is in telepathic communication with the current prey.

It's not a happy story, but it's pretty good. Three stars.

For Your Information: Brownian Motion, Loschmidt's Number and the Laws of Utter Chaos, by Willy Ley

Beginning with an explanation of the word 'gas' (which is as deliberately coined as 'radar' or 'Kleenex'), Ley goes on a whirlwind trip through the history of fluid dynamics. It's one of Ley's better pieces, though a little rushed and occasionally following the pattern of the Brownian Motion he ultimately explains.

But then, that's history for you. Four stars.

The Eskimo Invasion, by Hayden Howard

by Jack Gaughan

Out in the wilds of Canada, an anthropologist has made a terrible discovery: a tribe of "Eskimos" are really something else, the female of their species infinitely appealing…and able to have children every month. And they worship the Great Bear, a Cthulhu-esque entity that will devour/conquer/lead the world. Can Dr. West make it back in civilization to warn humanity?

This is a well-written tale, but the premise is so dumb that I found myself irritated with it after a night's contemplation. Two stars.

Galactic Consumer Report No. 2: Automatic Twin-Tube Wishing Machines, by John Brunner

The second in Brunner's Consumer Report series (the last dealing with budget time machines), this piece offers recommendations for and cautions against various models of "Wishing Machines," which are supposed to be able manufacture anything. Not as amusing as the last one, but diverting enough.

Three stars.

This piece is followed by Algis Budrys' books column, which I am increasingly enjoying. I read this latest one, describing Sheckley's Tenth Victim, Wilhelm and Thomas' The Clone, and Brunner's The Squares of the City for its humorous commentary and the illustration of the signs of good and bad editing and publishing.

When I Was Miss Dow, by Sonya Dorman

On a planet of amorphous proteans, a young, sexless being destined to become Warden of its people, takes on a human female form in order to more easily interact with the Terran mission to the planet. As Miss Martha Dow, said creature falls fake head over custom-built heels with an elderly biologist — and ultimately, the feelings are reciprocated.

I found myself really enjoying this unrestrainedly emotional piece, intertwining human and alien feelings in a vivid manner. This is the first published piece by Dorman using her full first name (previously, she had simply been "S"), and I'm delighted that she finally feels comfortable enough to use it. I know I always look forward to her byline!

Four stars.

Open the Sky, by Robert Silverberg

by Gray Morrow

At long last, we come to (what I believe to be) the conclusion of Silverberg's Blue Fire series. It's been a long trip, with five entries spanning more than a half-century of history. We've seen the Vorster religion arise, a spiritualist cult of the atom worshiping the blue flame of a cobalt reactor. We've watched as the cult schismed and the green-robed Harmonists made their sect more overtly religious and converted the colonists of toxic Venus. Last installment, the Harmonist martyr, Lazarus, was ressurected by Vorst for purposes unknown.

Now we know why: on Venus, the genetically modified human espers have developed faster than light teleportation. Vorst wants to use them to power the first interstellar starship. To do this, he needs to reunite the religions — and Lazarus owes him a favor. Luckily, Vorster knows this will all work out: he is a precog, after all…

The writing of this final installment is as good as ever, and it's nice to see all of the pieces fall into place. However, the story as a whole suffers from the common failing of all stories involving precognition. When you know how a story will, nay, must end, the tension is gone. All that's left is the exposition.

By itself, Open the Sky will be confusing and unengaging to the new reader. As the capstone to an epic, it serves its purpose adequately but not stunningly. Thus, I award three stars for the section, and four stars for the work as a whole, treating it as the serialization of a novel whose publication is as inevitable as Vorster's trip to the stars.

Journeys' End

All in all, it's been a good weekend, both in the real world and within the world of fiction. While Pohl's magazine could not quite consistently offer the spectacle that Jean-Paul of Joshua Tree treated us to, nevertheless, it did end up on the positive end of the ledger.

In any event, two trips for the price of one is a good deal! Why don't you take the June Galaxy along with you on your next jaunt and enjoy the same experience?

And while you're on your journey, tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest hits!

![[May 10, 1966] Rocky Jaunts (June 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1966] Top Heavy (April 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660310cover-388x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)