by Victoria Silverwolf

Vector, by Henry Sutton

Cover art by Roy E. La Grone.

Henry Sutton is the pen name of David R. Slavitt, a highly respected classicist, translator, and poet. As Sutton, he wrote a couple of sexy bestsellers, The Exhibitionist and The Voyeur. Now he's turned his hand to a science fiction thriller. Let's see if he's as adept at technological suspense as eroticism.

The story begins with the President of the United States announcing that the nation will stop all research into the use of biological weapons. Instead, only defensive research will take place.

That sounds great, but it means very little. Figuring out how to defend oneself against such weapons means you have to produce them and study them.

Next, the author introduces a number of characters in a tiny town in Utah and at the nearby military base. Guess what kind of secret research goes on at the base?

Pilot error during an unexpected storm leads to a virus being released on the town. The deadly stuff causes Japanese encephalitis, a disease with a high mortality rate. Survivors often have permanent neurological damage. There is no cure.

When a number of people come down with the disease, the military seals off the town. The phone lines are cut. One character is shot in the leg while trying to leave. Meanwhile, politicians in Washington try to cover up the disaster.

Our lead characters are a widowed man and a divorced woman who happened to be out of town when the virus hit the place. (The disease is normally transmitted via mosquito bites rather than from person to person. That's why he gets away with a relatively minor set of symptoms and she isn't sick at all.)

Besides giving us the mandatory romantic subplot, these two figure out there's more going on than the military is willing to admit. The man manages to sneak out of town and sets off on a long and dangerous hike across the wilderness, looking for a place where he can make a phone call to a trusted friend with government connections.

This is a taut political thriller in the tradition of The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May. Like those bestselling novels, both adapted into successful films, it creates a cynical, paranoid mood. I can easily imagine Vector as a motion picture.

Less of a science fiction story than last year's similarly themed bestseller The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton, Vector is a competent suspense novel. The narrative style is straightforward, meant for readability rather than profundity. The love story seems thrown in just to satisfy the expectations for mass market fiction.

Three stars.

Continue reading [May 20, 1970] Circus of Hells, Tau Zero, and Vector (May 1970 Galactoscope #2) →

![[June 28, 1970] Welcome to Blood Island (Four Filipino Fright Films)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700628movies-672x372.jpg)

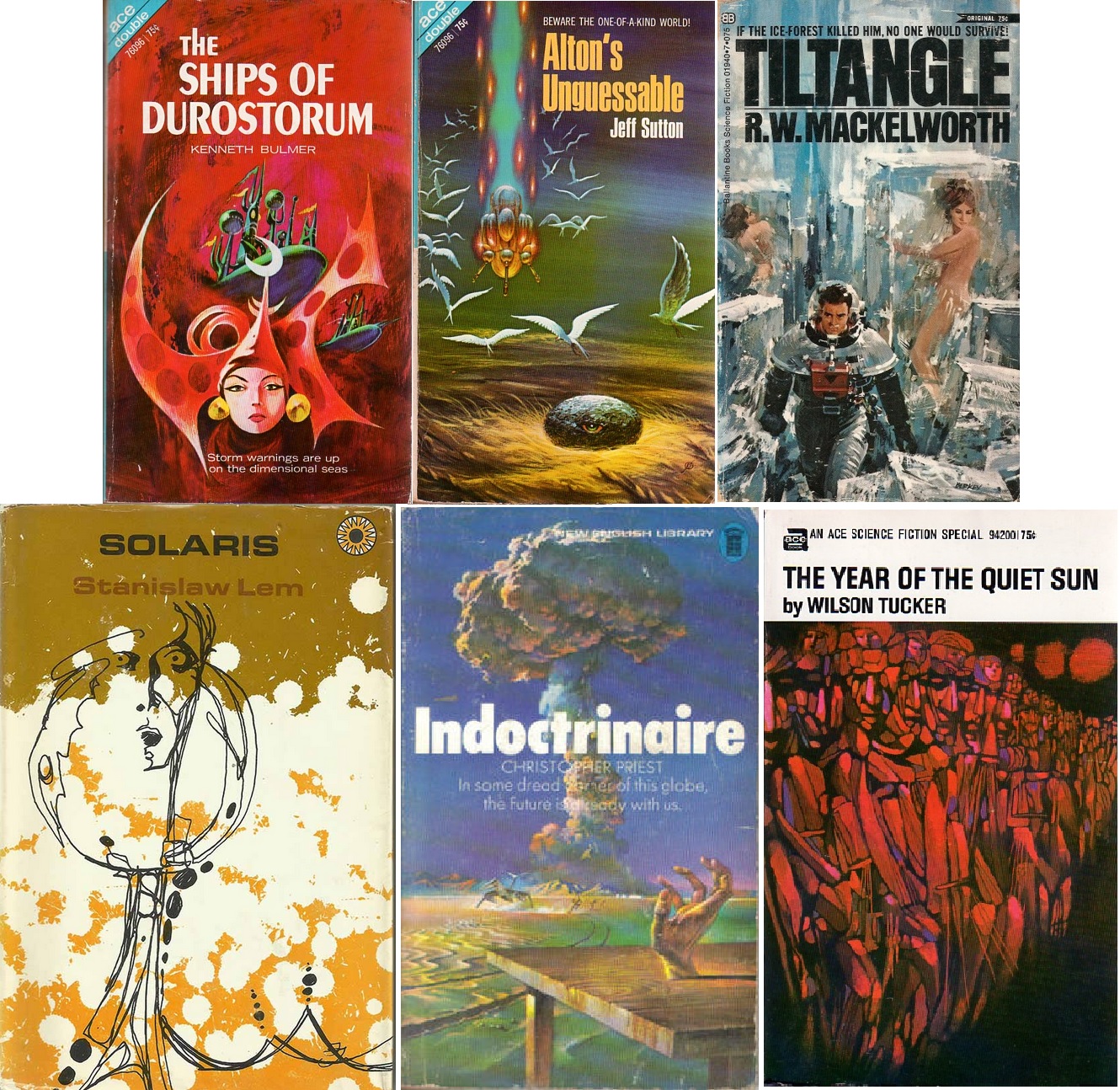

![[June 16, 1970] <i>Solaris</i>, <i>Year of the Quiet Sun</i>…and a host of others (June 1970 Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1970] Back From The Dead (Summer 1970 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1970] <i>Circus of Hells</i>, <i>Tau Zero</i>, and <i>Vector</i> (May 1970 Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700520covers-672x372.jpg)

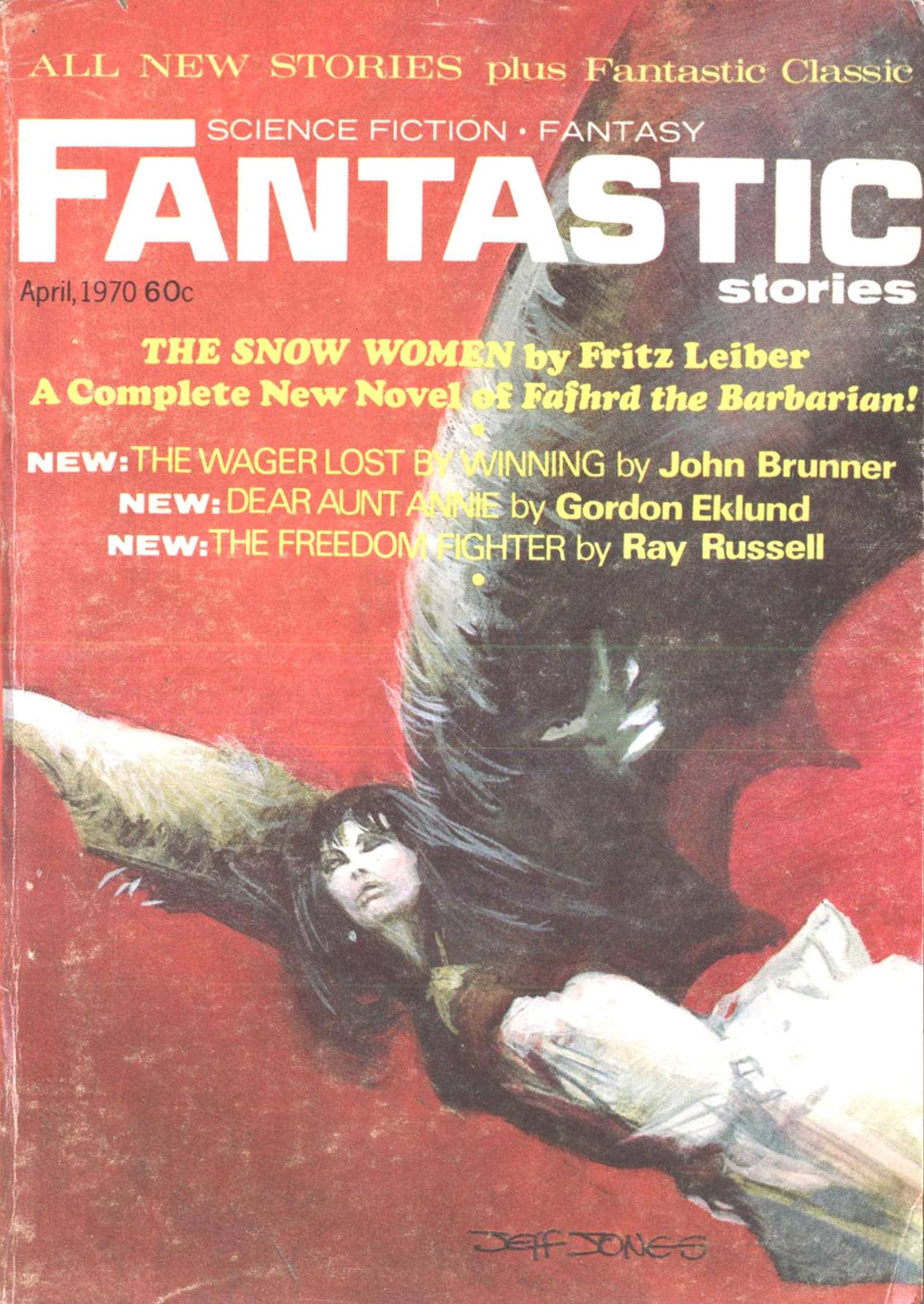

![[May 12, 1970] War and Peace (June 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[April 16, 1970] Junk Day for Ice Crowns (April 1970 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1970] Baby, It's Cold (And Dark) Outside (April 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

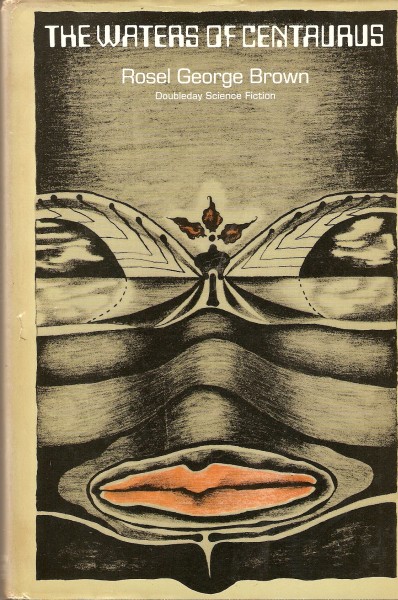

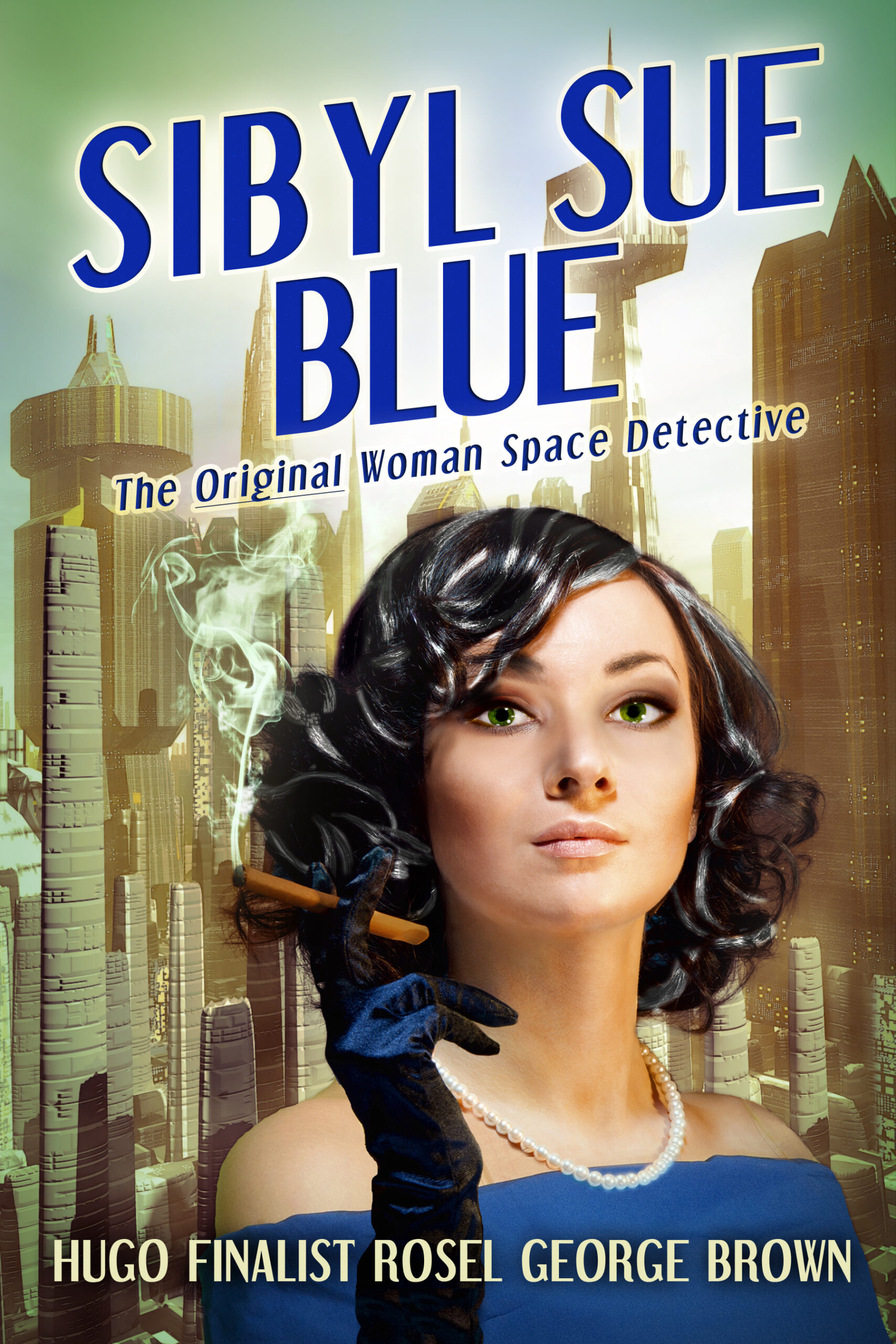

![[March 6, 1970] <i>The Waters of Centaurus</i>, <i>And Chaos Died</i>, and <i>High Sorcery</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700306covers-672x372.jpg)

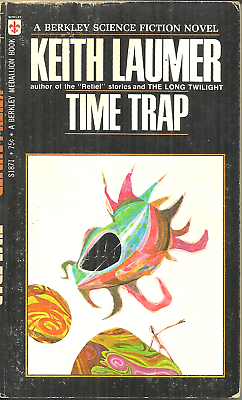

![[February 18, 1970] <i>Time Trap</i>, <i>This Perfect Day</i>, <i>Whisper from the Stars</i>, and <i>The Incredible Tide</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700220covers-672x372.jpg)

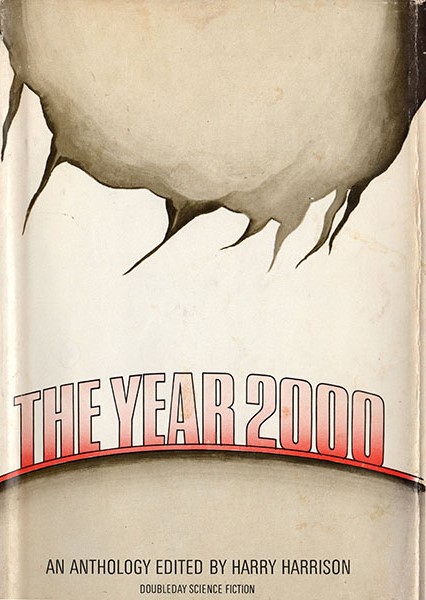

![[February 10, 1970] Thirty Years To Go (<i>The Year 2000</i>, a science fiction anthology by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/THEYEARF51970.jpg)