by Kaye Dee

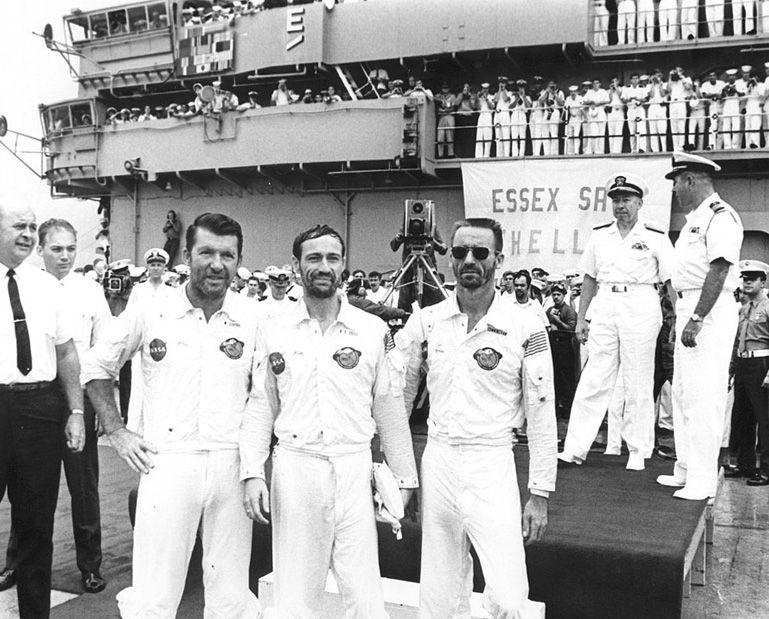

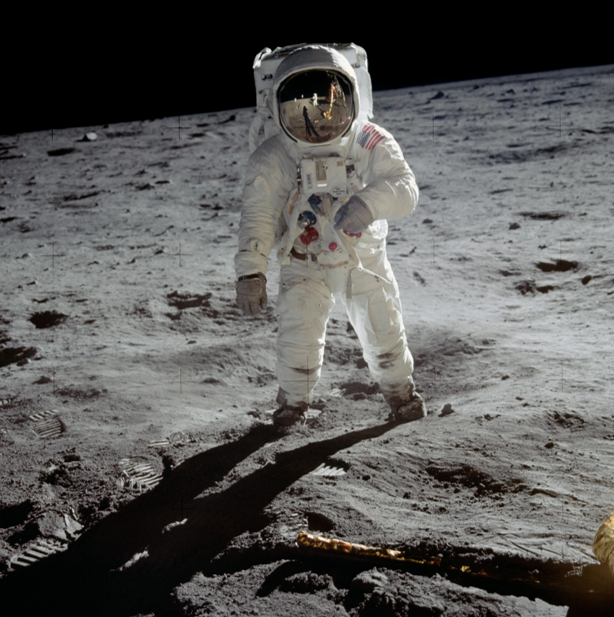

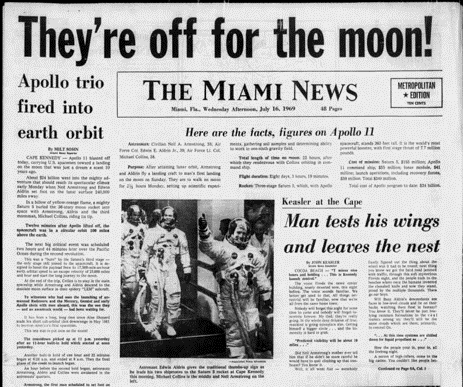

The crew of Apollo-11 has returned home in triumph, splashing down safely in the Pacific Ocean on 24 July US time, at the end of their historic mission. The New York Times Editorial of 20 July has called their epic adventure “more than a step in history; it is a step in evolution.” Those footprints (well, bootprints, like Col. Aldrin's above) on the Moon mark the beginning of humanity's giant leap from its home planet into the cosmos.

Despite their hero status, right now the crew of Apollo-11 are pariahs – in quarantine to ensure that they have not brought home any nasty surprises from the Moon in the form of unknown pathogens. But alongside the treasure trove of Moonrocks, what they have brought home is a stunning visual record of Mankind's "greatest adventure", and I have waited a little to prepare this article so that it could be illustrated with many of the images taken during the flight (which had not been developed and distributed until now). I hope you’ll agree that it has been worth the delay.

The Apollo-11 mission has been epic in every sense of the word – so much so, that my intended two-part article has evolved into a three-part story, the final chapter to come after the astronauts are released from their quarantine.

A Smooth Cruise

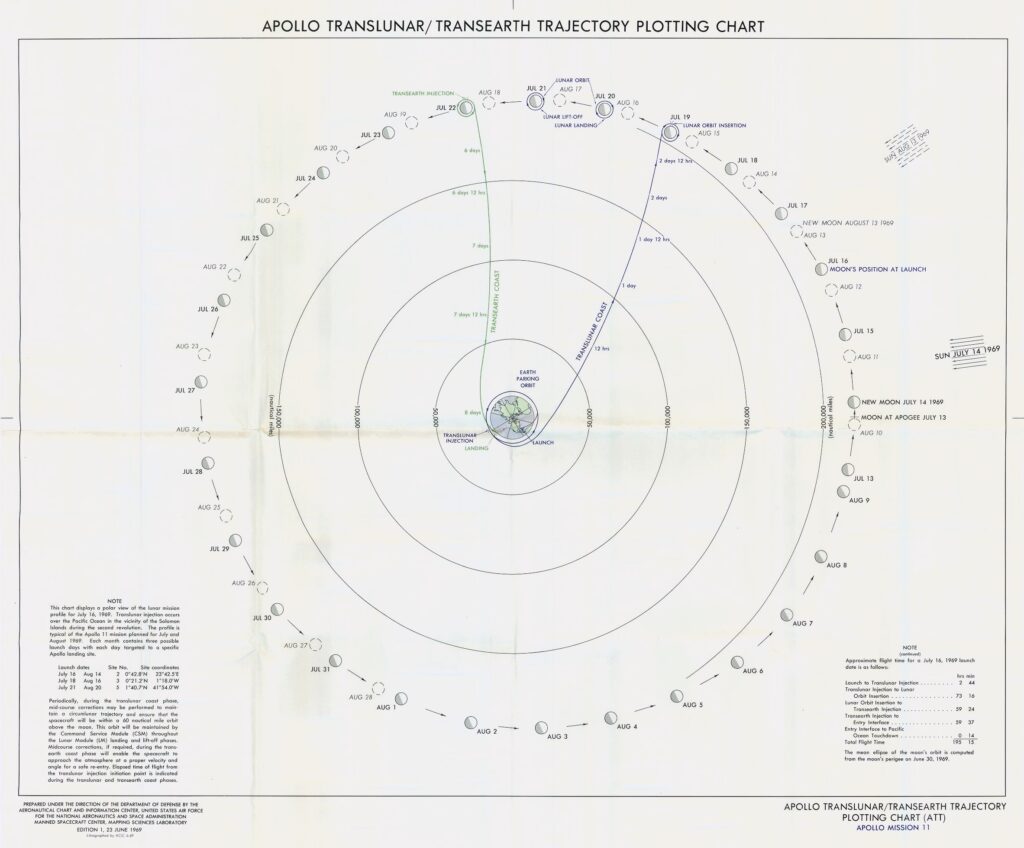

At the end of Part 1, we left the Apollo-11 crew on their coast to the Moon, which was largely routine and uneventful. Despite the intrinsically dangerous nature of the Apollo-11 mission, the flight was, overall, probably the most trouble-free Apollo mission to date. Certainly, the Operations Supervisor at the Honeysuckle Creek Manned Space Flight (MSFN) Tracking Station has described it as “a very smooth mission from our perspective”, and I understand that Mission Control in Houston thought the same, despite the stresses inherent in such a historically significant undertaking as the first Moon landing.

Coming to You in Living Colour

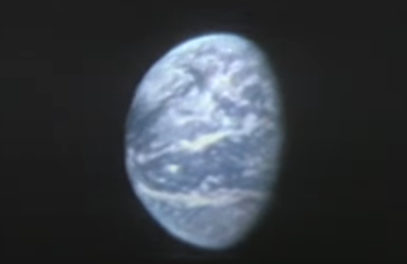

34 hours into the flight, Mr. Armstrong, Col. Aldrin and Col. Collins gave their first public television broadcast. Highlights of the 36-minute transmission (in colour for those countries with colour TV service) included views of the Earth, Lunar Module (LM) Pilot Aldrin demonstrating zero-g push-ups and “Chef” Collins dishing up a space food chicken stew.

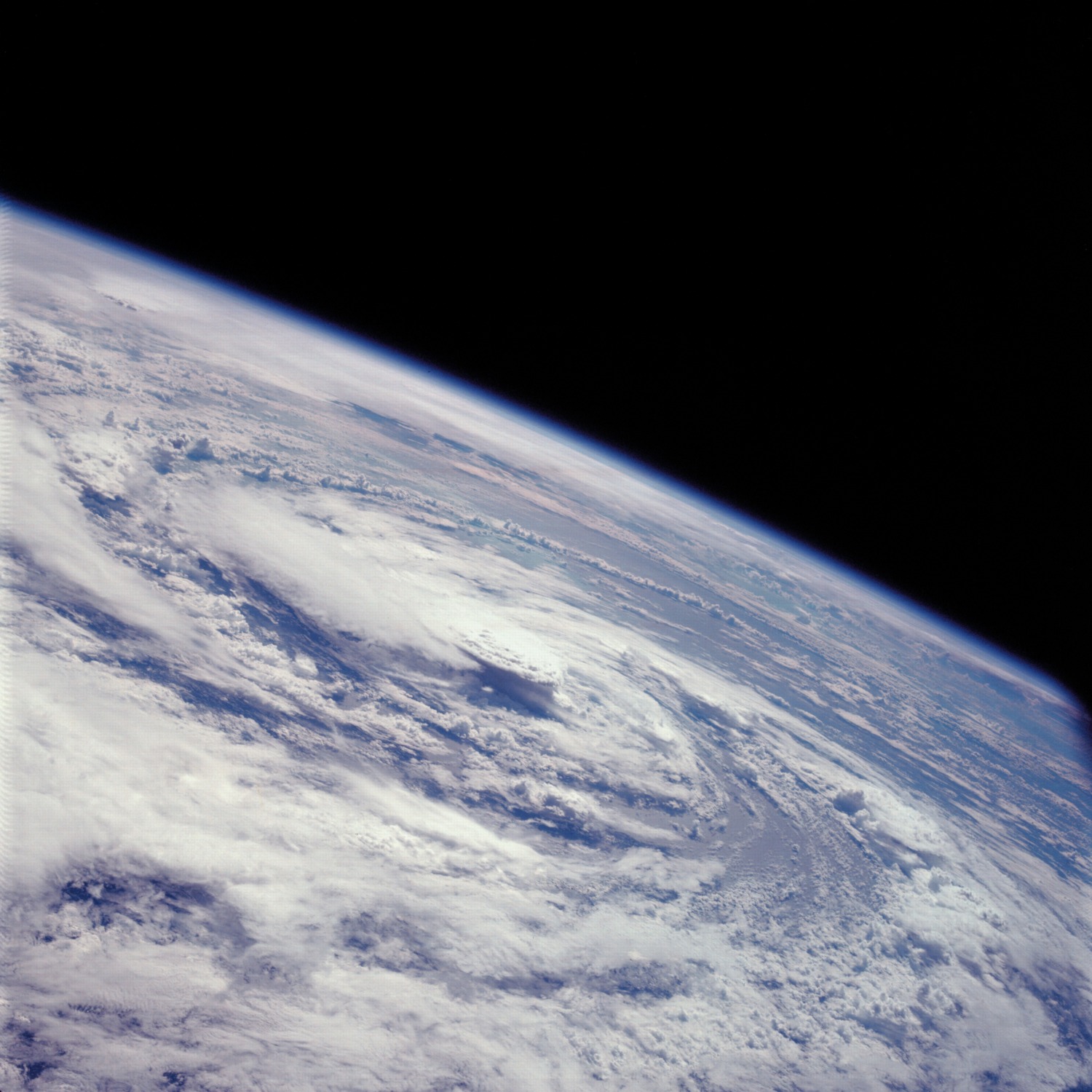

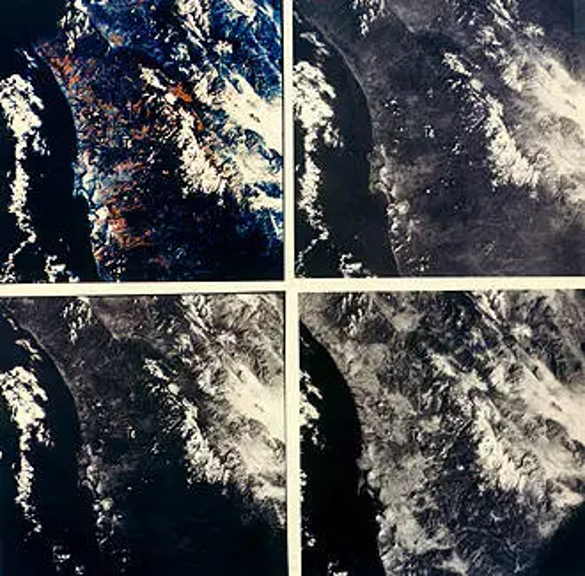

Compare the resolution of this photo taken by the crew with the television image of a similar view of the Earth at around 10,000 nautical miles

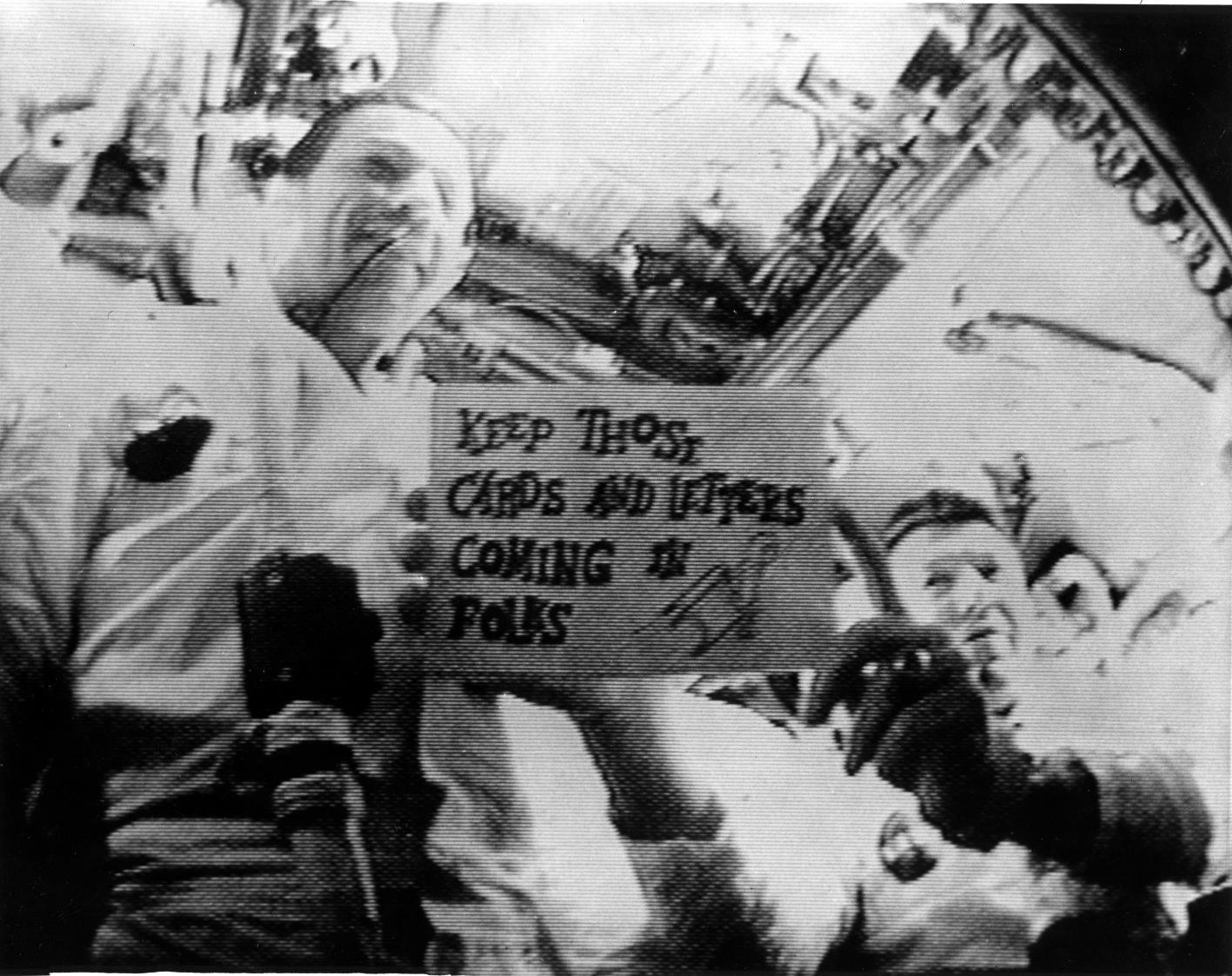

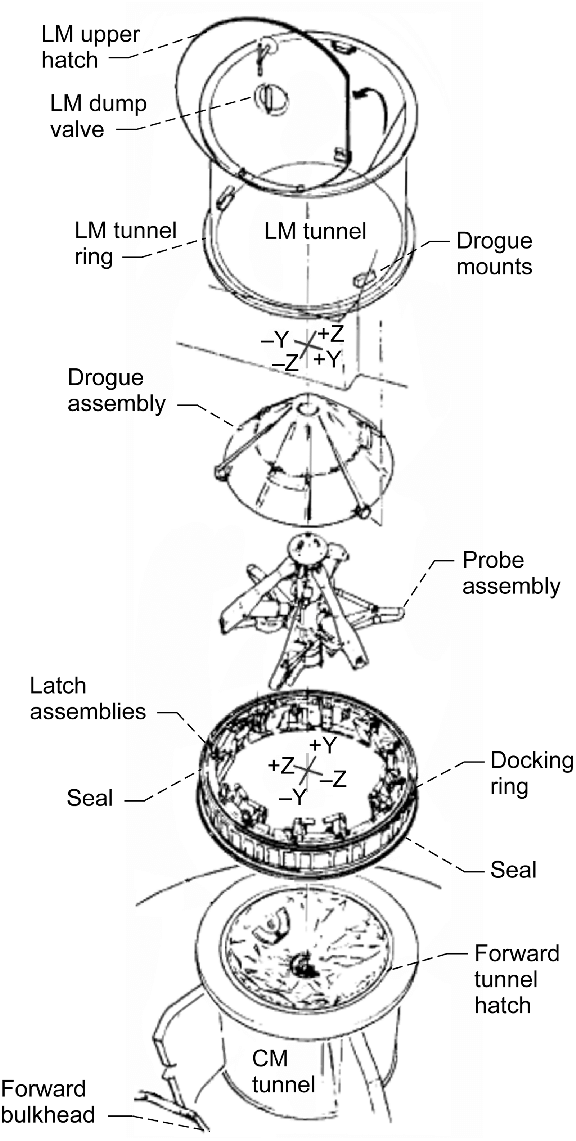

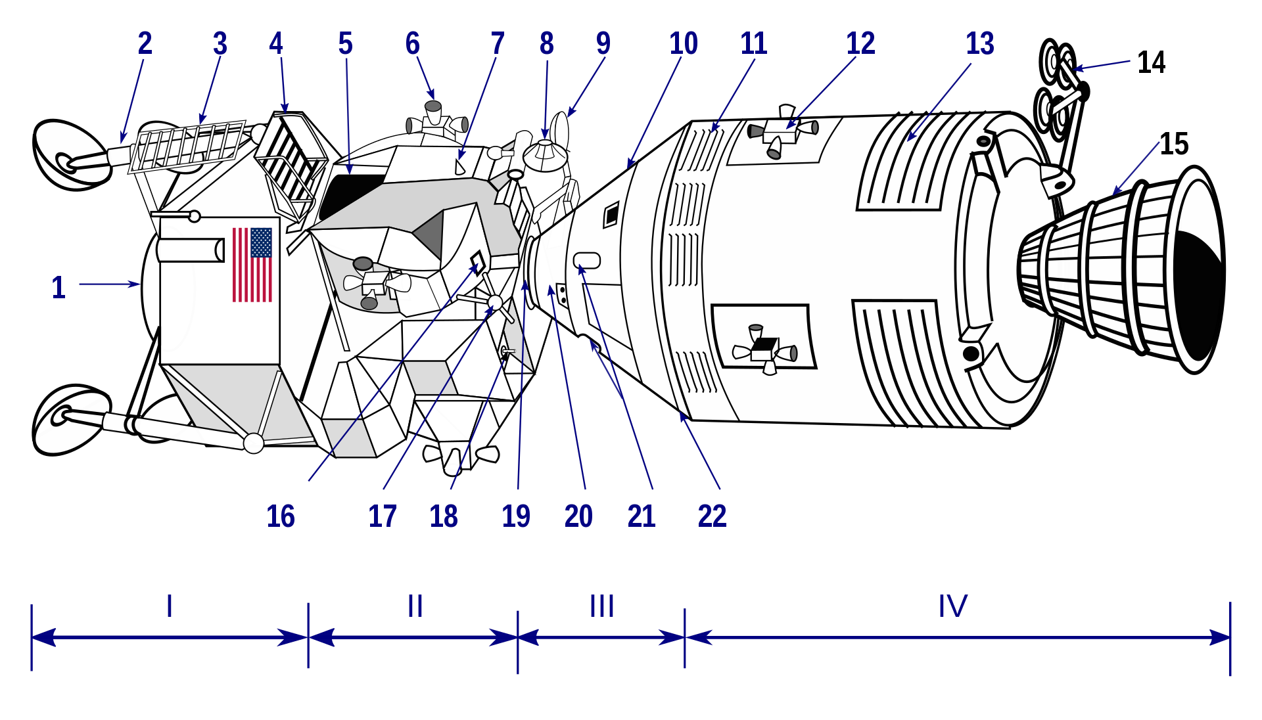

Another television transmission took place 55 hours after launch, with a 96-minute colour broadcast. Shown live in the US, Japan, western Europe and much of South America, this show again included views of the Earth, now 201,300 miles away. Viewers could see the removal of the probe and drogue docking apparatus and the opening of the spacecraft tunnel hatch to the LM, with Command Module (CM) Pilot Collins making jokes about his non-union “stagehands” (Armstrong and Aldrin).

Col. Aldrin entered the LM first, followed by Mr. Armstrong, providing a tour around the vehicle that would land the first human beings on the Moon. Aldrin also described the Moonwalking gear waiting to be used.

Aldrin in the LM during its first checkout. His sunglasses were specially developed by Australian ophthalmologist Dr. John Colvin

Into Lunar Orbit

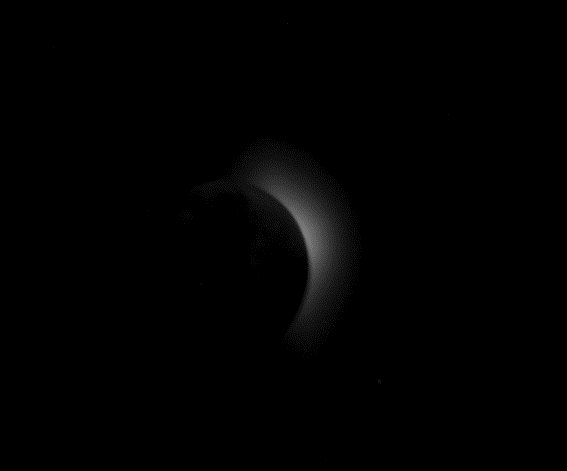

On mission day four, Col. Collins swung the Command Service Module (CSM) around, so that the crew could look at the rapidly approaching Moon, its crater-pocked surface now filling their windows. As the spacecraft entered the Moon’s shadow, Mr. Armstrong noted “Now we are able to see stars again and recognise constellations for the first time on the trip. The sky is full of stars, just like the nights on Earth. But all the way here, we’ve only been able to see stars occasionally… but not recognise any star patterns.”

An eerie view approaching the Moon in its shadow, with the solar corona and dimly Earthlit craters appearing around the lunar rim

An eerie view approaching the Moon in its shadow, with the solar corona and dimly Earthlit craters appearing around the lunar rim

Like Apollo-8 and 10, the CSM engine burn required to place Apollo-11 into lunar orbit had to occur behind the Moon, with the crew out of direct contact with the Earth. Shortly before they disappeared behind the Moon, while in contact with the MSFN station near Madrid, the astronauts described the lunar surface they could see through their windows, with Col. Collins likening its colour to “Plaster of Paris grey.”

After a Trans-Lunar Coast that lasted for 73 hours, 5 minutes and 35 seconds, a 5 minute 57.53 second burn placed Apollo-11 exactly where it should be – in a lunar orbit of 195 by 69 miles. When reporting to Mission Control on the Lunar Orbit Insertion burn, once contact was re-established, Col. Collins could only say “It was like… perfect.”

Around the Moon

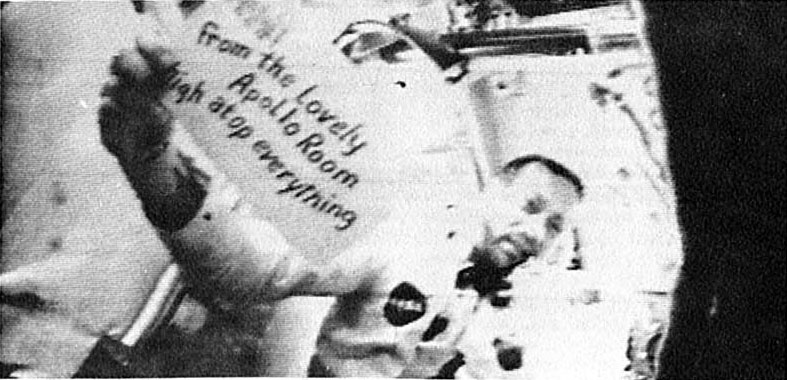

Orbiting the Moon, in their Columbia, like the heroes of Jules Verne’s “Autour de la Lune” (Around the Moon) in their Columbiad, at 78 hours and 20 minutes into the mission Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins offered viewers back on Earth a 40-minute live colour television transmission that showed spectacular views of the lunar surface and the approach path to the LM Eagle’s planned landing site. As the spacecraft prepared to go behind the Moon again, Aldrin quipped, “And as the Moon sinks slowly in the west, Apollo-11 bids good day to you,” paraphrasing Lowell Thomas’ famous travelogue sign-off to fit the occasion.

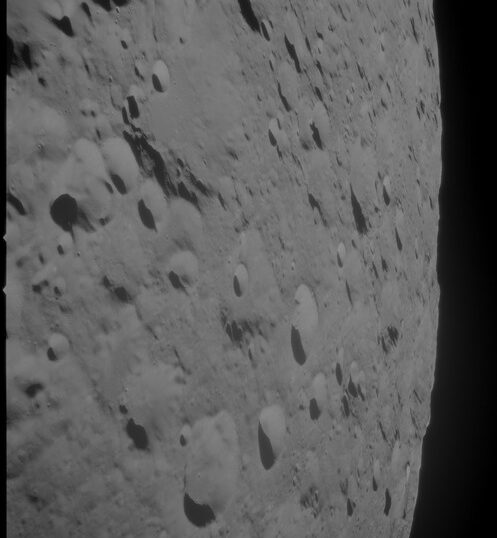

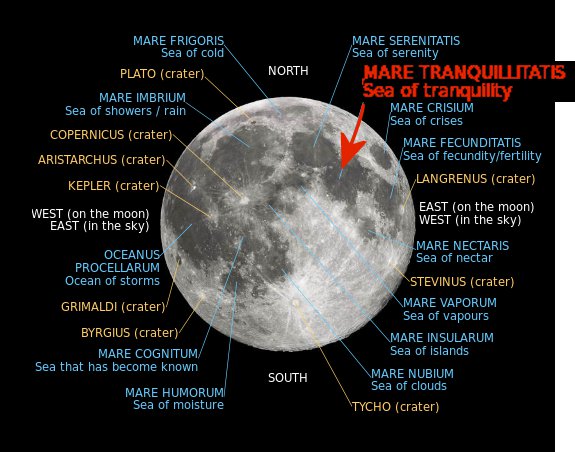

As Apollo-11 approached the Sea of Tranquility for the first time, it was early dawn on the surface below, with long, black shadows stretching across the cratered Moonscape.

Just over two hours later, CMP Collins initiated a second engine burn of 16.88 seconds, to place the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit, ready for the LM to depart for the lunar surface. This burn was critical, because if it was even two seconds too long it could put Apollo-11 on a collision course with the other side of the Moon!

Checking out the LM

A little over 81 hours after launch, during their fourth orbit of the Moon, LMP Aldrin entered the LM, to power up and checkout the spacecraft systems. Then Commander Armstrong and Col. Aldrin called Mission Control in Houston for the first time from the lunar landing vehicle, using the “Eagle” callsign.

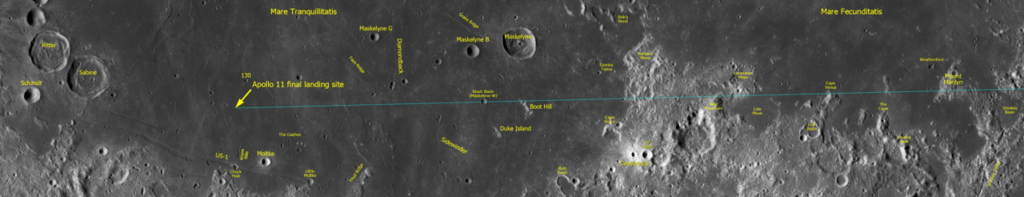

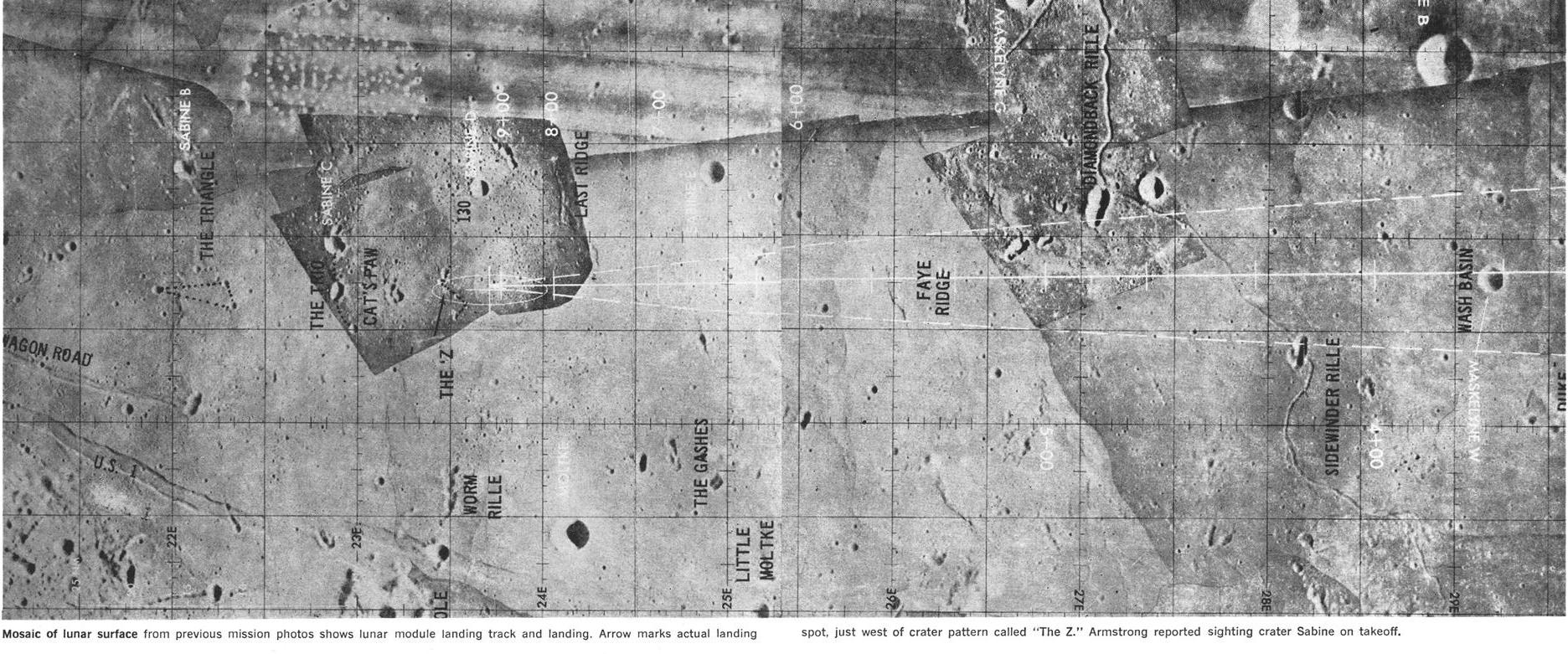

A view of the approach to the Apollo-11 landing site, captured during the LM checkout period. It has been annotated with formal and unofficial names to show the approach path

A view of the approach to the Apollo-11 landing site, captured during the LM checkout period. It has been annotated with formal and unofficial names to show the approach path

Once this communications test was completed, the astronauts began to prepare for a sleep period. Collins suggested that Armstrong and Aldrin take the most comfortable sleeping positions in the Command Module, so they would get a good rest before the landing attempt. He was undoubtedly concerned about the possibility of an error due to overtiredness, which could have catastrophic consequences for the mission and the crew. The possibility of having to return to Earth alone if disaster should strike the lunar module crew seems to have weighed on Col. Collins’ mind, as he mentioned his understandable apprehension in several interviews prior to the flight.

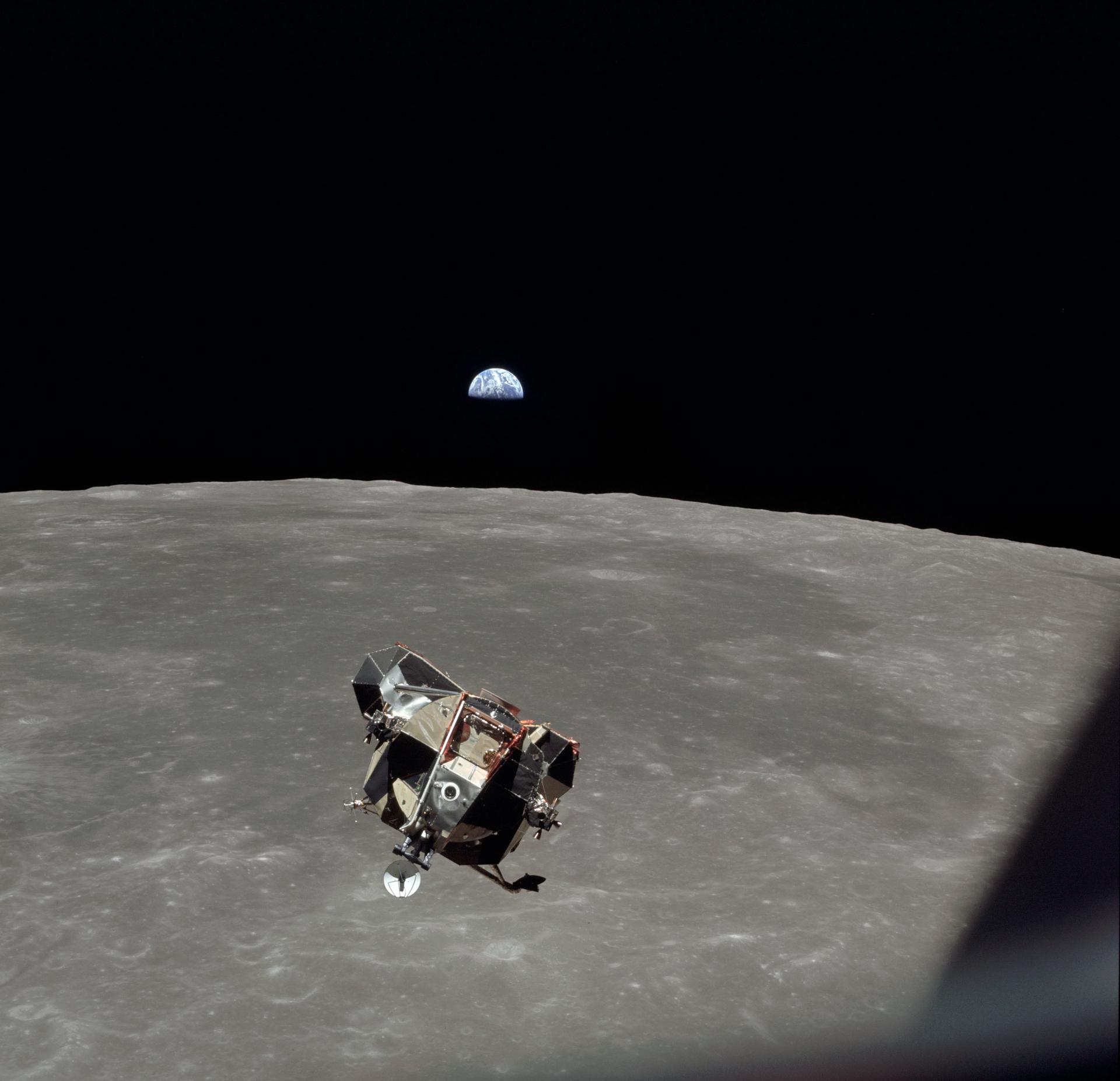

Just before the sleep period, the astronauts captured another glorious vision of the Earth hovering above the lunar surface that is certain to become as iconic as Apollo-8’s Earthrise image

The Big Day Arrives

On 20 July (21 July in the eastern hemisphere, including Australia), astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin donned their spacesuits in the CM equipment bay, before entering Eagle for their descent to the lunar surface. After sealing the hatch and completing the final checkout of the LM, they extended Eagle’s landing gear and prepared to separate from the CSM.

This manoeuvre took place behind the Moon, during the 13th orbit, so as to place Eagle on the correct descent trajectory to touch down at the ALS-2 landing site. The LM moved away from Columbia and pirouetted around so that Col. Collins could inspect the vehicle and ensure that Eagle was totally ready for its historic descent to the Moon. “The Eagle has wings,” Armstrong assured Mission Control, as he and Aldrin put the craft through its paces. A nine-second Reaction Control System engine burn by the CSM then separated the two spacecraft to a safe distance apart

Meanwhile, Back in Mission Control

In focussing on the astronauts, it’s easy to forget the flight controllers and their support teams monitoring, guiding and approving every stage of a manned space flight.

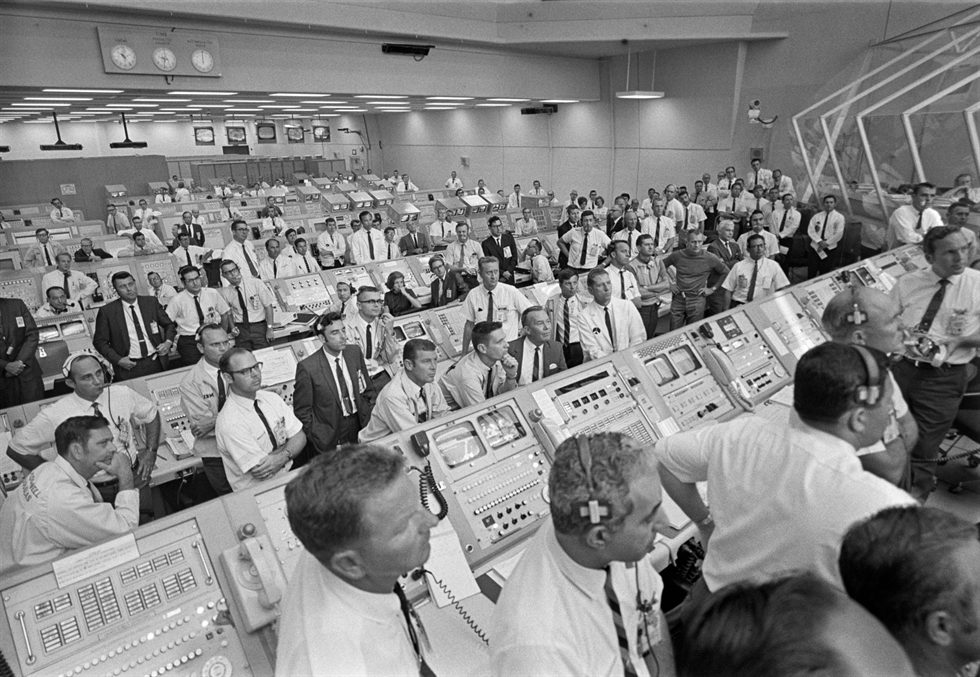

Flight Director Kranz (second from right) in the MOCR

Flight Director Kranz (second from right) in the MOCR

For the critical lunar landing phase of Apollo-11, the Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR), better known as Mission Control in Houston, was staffed by the White Team of flight controllers, under Flight Director, Mr. Eugene Kranz, usually known as Gene. The space specialists now filling roles that did not even exist outside the pages of science fiction a decade ago, have an average age of just 26 years! Rookie astronaut Charles Duke served as CAPCOM, the direct contact with the astronauts.

CAPCOM Duke, with Apollo-8's Jim Lovell, the Apollo-11 backup commander, listening in

CAPCOM Duke, with Apollo-8's Jim Lovell, the Apollo-11 backup commander, listening in

As the time for Apollo-11’s historic landing approached, every available audio outlet in Mission Control had a headset plugged into it, to listen to the spacecraft communications channel. Senior NASA officials and astronauts, including Alan Shepard and John Glenn, positioned themselves in the MOCR to be eyewitnesses to the fulfillment of President Kennedy’s bold challenge of 1961. The families of the crew were also present.

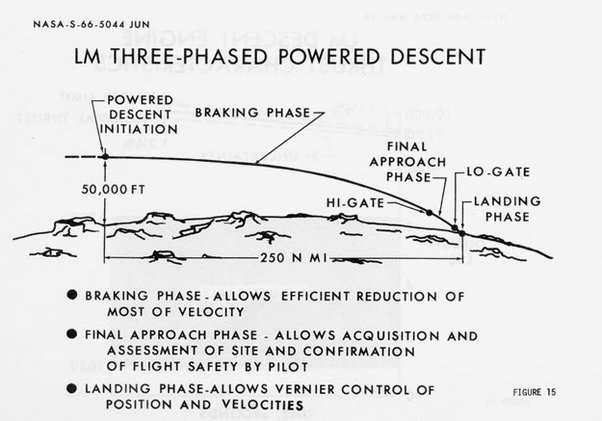

The Eagle Stoops to the Moon

The Descent Orbit Insertion (DOI) burn needed to land Eagle safely on the Moon, required a 30 second firing of the LM descent engine. All the telemetry data being received at Mission Control indicted that everything was going to plan, but the landing on the Moon’s surface was (aside from re-entry) the most dangerous part of the flight: within forty minutes, the Eagle and its crew would either “land, crash or abort”, determining the success of the mission.

At 102:33:05.01 GET (Ground Elapsed Time) Eagle fired its descent engine to commence the landing sequence. Unexpectedly, the burn placed the LM 4.6 miles further downrange than planned, resulting in the landing point being 4.6 miles beyond the designated ALS-2 site. It seems the cause of this discrepancy was some residual pressure in the tunnel connecting the CM and LM when the two craft undocked (the tunnel should have been in vacuum, but had not been fully decompressed). This pushed the spacecraft apart with more velocity than planned.

With the LM’s legs facing the flight path, the astronauts were essentially flying backwards and unable to see where they were going, although they could see landmarks passing by and knew where they were as they descended towards the Moon’s surface.

Problems Arise

As the LM’s altitude decreased, the on-board radar data was critical for evaluation and comparison with altitude data from the tracking stations on Earth. But a potential electrical problem with the radar was just one of an increasing number of problems that began to arise as the LM dropped towards the lunar surface. Communications difficulties with Mission Control meant that Col. Collins in Columbia had to relay some messages between Houston and Eagle.

Nevertheless, when Flight Director Kranz polled his team, they were all prepared to give the “Go!” for powered descent. Guidance Officer Steve Bales had the only reservations, noting that the spacecraft was moving a little faster than planned. As a result, Eagle was going to land further downrange than planned, in what was expected to be a rockier area.

Abort?

At 102:38:22 GET the astronauts received a 1202 alarm, which meant their computer was overloaded by irrelevant data from the rendezvous radar (which should have been switched off) and couldn’t do all the tasks in the time available. Would the landing have to be aborted?

The backroom boys supporting Mission Control. They realised the alarms were minor issues

The backroom boys supporting Mission Control. They realised the alarms were minor issues

With the lives of Commander Armstrong and Col. Aldrin – and the success of the entire mission – in their hands, Guidance Officer Bales and his support team fortunately recognised the issue immediately and were able to give assurance that the computer would perform, nevertheless, and landing could proceed. When a similar 1201 alarm sounded, with Eagle just 2,000 ft above the lunar surface, they once again gave a positive response for the landing to continue.

Heading for Touchdown

With four minutes until touchdown, communications between the LM and Earth finally strengthened and stablised. Another rollcall of the flight controllers gave the landing the “Go!” to proceed.

At 9,000 ft, the LM began to drop its legs to point down to the Moon’s surface. Mission Commander Armstrong was trained to land the LM, controlling the spacecraft’s flight while looking out the window at the landing site. Col. Aldrin’s role was to concentrate on the display panel and provide Armstrong with the information he needed as he guided the Eagle safely down to the lunar surface. At this point, the flight control team back on Earth could do no more for the landing: everything now depended on the skill and teamwork of Armstrong and Aldrin.

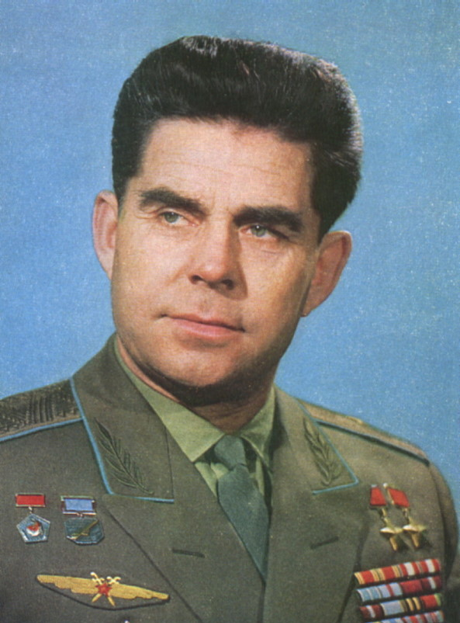

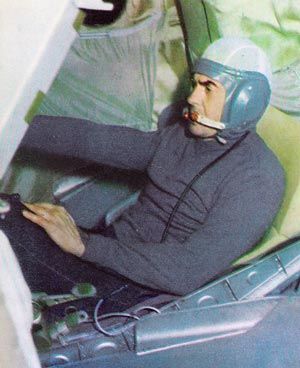

Commander Armstrong flying the LM to touchdown in a training simulation

Commander Armstrong flying the LM to touchdown in a training simulation

As an experienced test pilot, Neil Armstrong chose to fly the final landing phase (about the last ¾ of a mile to the touch down spot from a thousand feet) manually, like flying a helicopter. This enabled him to exercise his judgement to fly beyond the intended landing position, when it became clear that “a gigantic crater and lots of very big rocks” made it a very unfavourable position to touch down.

Time is Running Out!

Extending his downrange flight, Mr. Armstrong searched for a more suitable landing site, but time and fuel were fast running out. At around 250 ft altitude, an amber light warned that only 5 per cent fuel remained – there were only 94 seconds left to land! Approaching 100 ft above the Moon’s surface, the downblast of the LM’s descent engine began to stir up the dust, making it difficult for Armstrong to gauge their velocity, or sight a safe place to land, by observing surface features.

View from the LM window about 30 seconds before touchdown, with the shadow of an LM leg and contact probe against the lunar surface

View from the LM window about 30 seconds before touchdown, with the shadow of an LM leg and contact probe against the lunar surface

Finally, with just 10 seconds of fuel left, as Armstrong saw the shadow of the LM stretching in front of him, Col. Aldrin called “Contact light!”, indicating that one of Eagle’s landing leg probes had touched the lunar surface. So gently that the crew barely noticed it, the first manned spacecraft from Earth touched down on the surface of the Moon! It was 102:45:40 GET, 15:17CDT on 20 July in the United States. (For us on the east coast of Australia, it was 6.17am on a cold winter’s morning!)

“The Eagle has Landed!”

Inside the Eagle, Mr. Armstrong and Col. Aldrin apparently looked across at each other and silently shook their space-gloved hands, celebrating the success of their flight in reaching the Moon’s surface. But as historic as that safe landing was, the astronauts had to immediately prepare the LM for a sudden abort ascent in the event the landing had damaged the Eagle, or some other emergency arose.

Eagle's shadow on the Moon's surface following the landing. This view was taken after the Moonwalk and the astronaut's bootprints can be seen on the surface

Eagle's shadow on the Moon's surface following the landing. This view was taken after the Moonwalk and the astronaut's bootprints can be seen on the surface

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!” Apollo-11 Commander Armstrong announced proudly to Mission Control and the world, as soon as he was sure that Eagle had touched down safely. Since the descent stage of the LM will remain on the Moon (and presumably be designated as a historic monument in the future), it was an appropriate gesture to identify its landing site as Tranquility Base – Earth’s first outpost on another world.

In Mission Control, the flight controllers briefly celebrated, before Flight Director Kranz called for a “Stay/No Stay” decision from his team just one minute after landing. There were abort points at three and twelve minutes after landing – after that, the astronauts would have to wait for Columbia to go around the Moon again. At each decision point, flight controllers approved Eagle to stay on the lunar surface.

The Loneliest Man

While Eagle’s crew on the Moon were in constant communication with Mission Control, CMP Collins was orbiting the Moon, relying on events being relayed to him so that he knew what was happening. After forty minutes of complete isolation behind the Moon on each orbit, he could talk and listen to the Earth for seventy minutes, through either the Goldstone or Tidbinbilla DSN stations. However, he only had about eight minutes in direct contact with Eagle each time his orbit passed over Tranquility Base. Fortunately, Columbia was in the contact zone when Eagle was landing, so that he could hear the verbal exchanges of the touchdown, but his general communication isolation from the Earth, and from his crewmates, earned Mike Collins the nickname “the Loneliest Man”.

Where Did They Land?

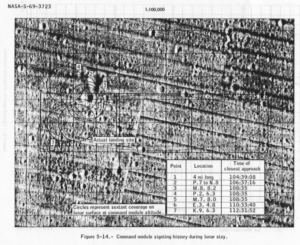

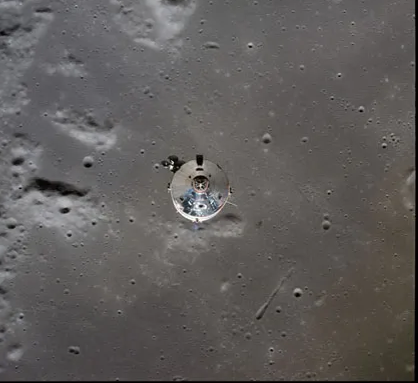

Each time he passed over the Sea of Tranquility, Collins scanned the lunar surface for signs of the LM, hoping to spot the spacecraft (he never did) and any landmarks that would assist in identifying Eagle’s actual landing site: since Commander Armstrong had taken the LM further downrange than planned in search of a safe landing site, its exact position on the lunar surface was uncertain.

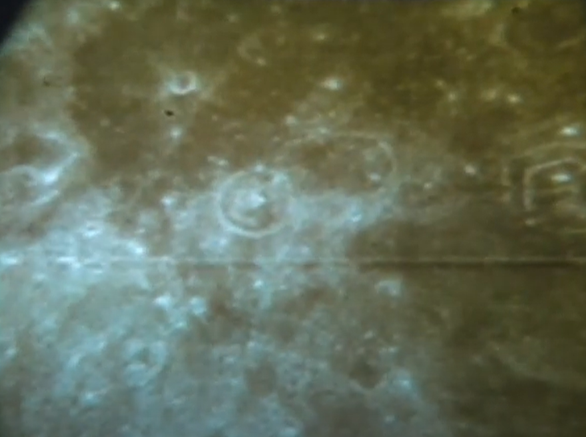

Annotated NASA image showing Collins' attempts to sight the Eagle's landing site. Very close, but no cigar!

Annotated NASA image showing Collins' attempts to sight the Eagle's landing site. Very close, but no cigar!

Using huge lunar maps and data from the spacecraft and tracking stations, the Mapping Sciences Laboratory in Houston had narrowed the landing site down to a 5-mile radius, but Eagle’s crew could not identify anything of significance from their position. It wasn’t until Apollo-11 was halfway back to Earth that a chance remark by Mr. Armstrong finally helped the mappers to pinpoint the location of the landing site!

Going for a (Moon) Walk

Apollo-11’s flight plan called for a four-hour rest period after touching down on the Moon. However, as everything had gone according to schedule, the astronauts were eager to take their first steps on the lunar surface before their rest period. Two hours after landing, Armstrong requested Mission Control’s approval to postpone the scheduled sleep period and go out on the lunar surface straight away.

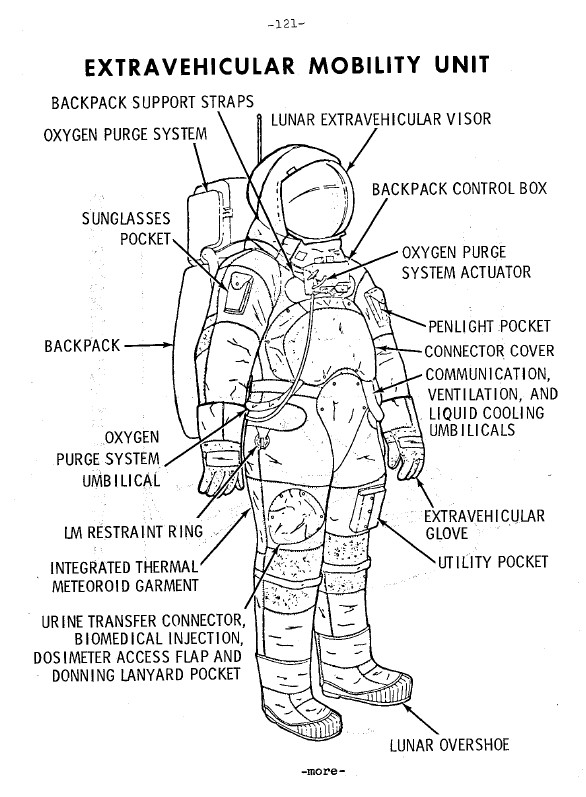

Mission Control concurred, and Armstrong and Aldrin began to carefully don their lunar Extravehicular Activity (EVA) spacesuits. In the cramped space of the LM’s cabin, surrounded by vulnerable switches and instrument panels, this took considerably longer than the expected preparation time of about two hours. Every move in the donning process had to be meticulously carried out and checked, ultimately taking around 3½ hours for the crew to be fully suited up and ready for Mankind’s historic first steps onto the Moon.

Preparing for the Moonwalk Broadcast

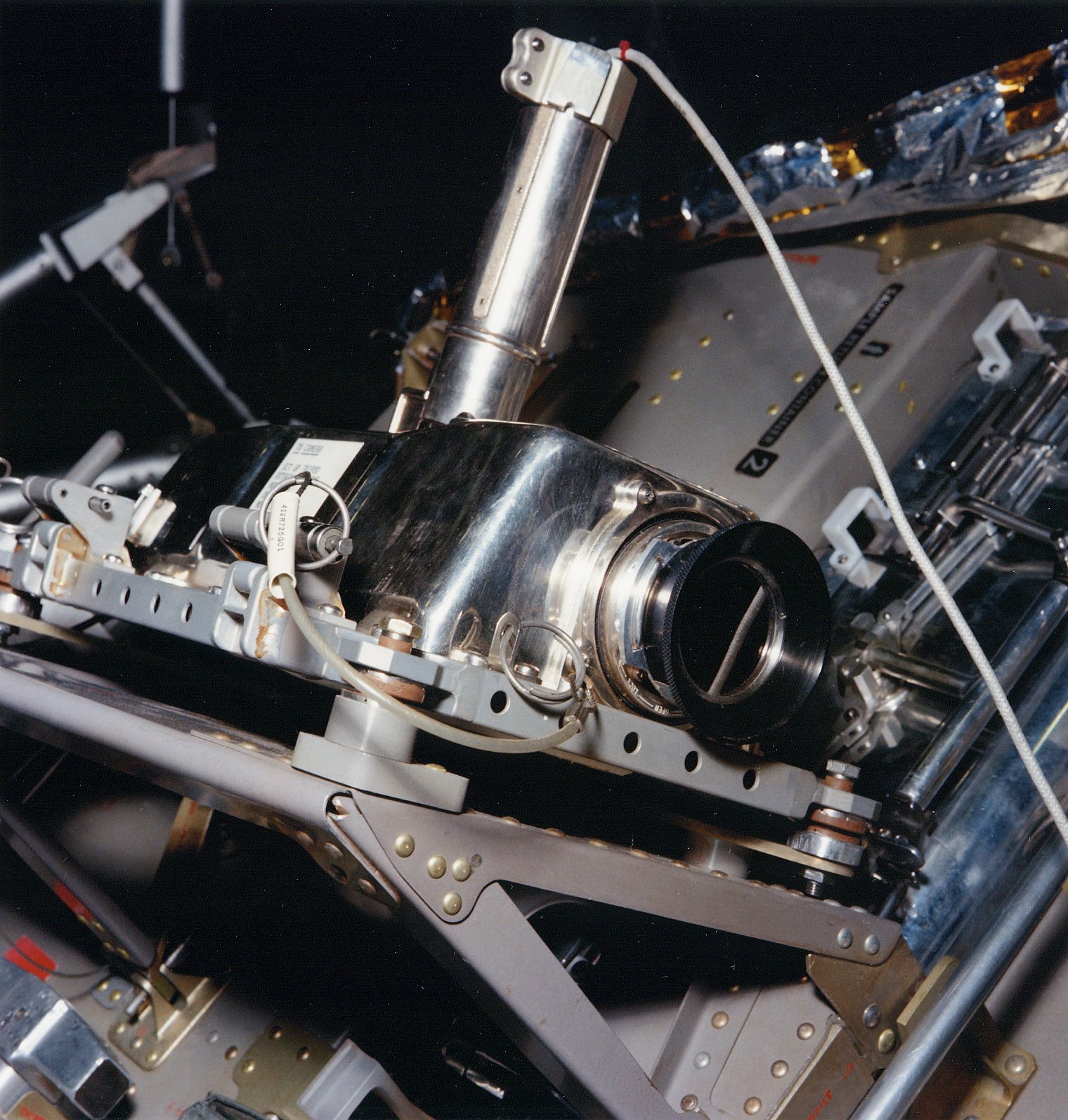

Like me, I’m sure you will be surprised to learn that NASA originally intended to provide only radio coverage of Apollo-11’s history-making first steps on the Moon! It was not until early this year that the decision was finally made to include television coverage of the lunar EVA! However, as a contingency, Westinghouse (which produced the colour television camera used in the Apollo 10 and 11 Command Modules) had been contracted to develop a compact television camera that could be used on the lunar surface. This slow-scan black and white camera has a vertical resolution of 320 lines scanned at 10 frames per second, designed to work with the small transmission bandwidth available from the LM on the Moon, which was not sufficient for a standard TV signal.

The Westinghouse Apollo-11 Lunar Surface Camera was initially mounted in the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA), in the LM Descent Stage, positioned so that it could see the astronauts descending the ladder to step onto the lunar surface. Because of its design, and the limited space available within the MESA, the camera had to be mounted upside down. This meant that the transmitted view of Mission Commander Armstrong coming down the ladder was upside down, and a special switch had to be activated at the reception station on Earth to invert the image to the right way up. This step was not necessary when the camera was removed from the MESA and set up on the Moon’s surface itself to cover the activities of the lunar EVA.

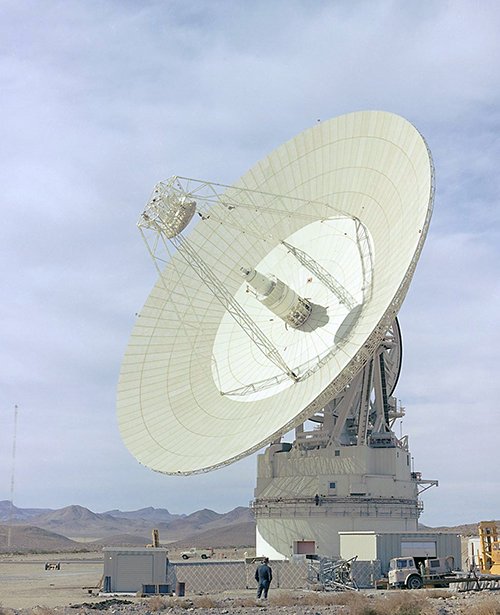

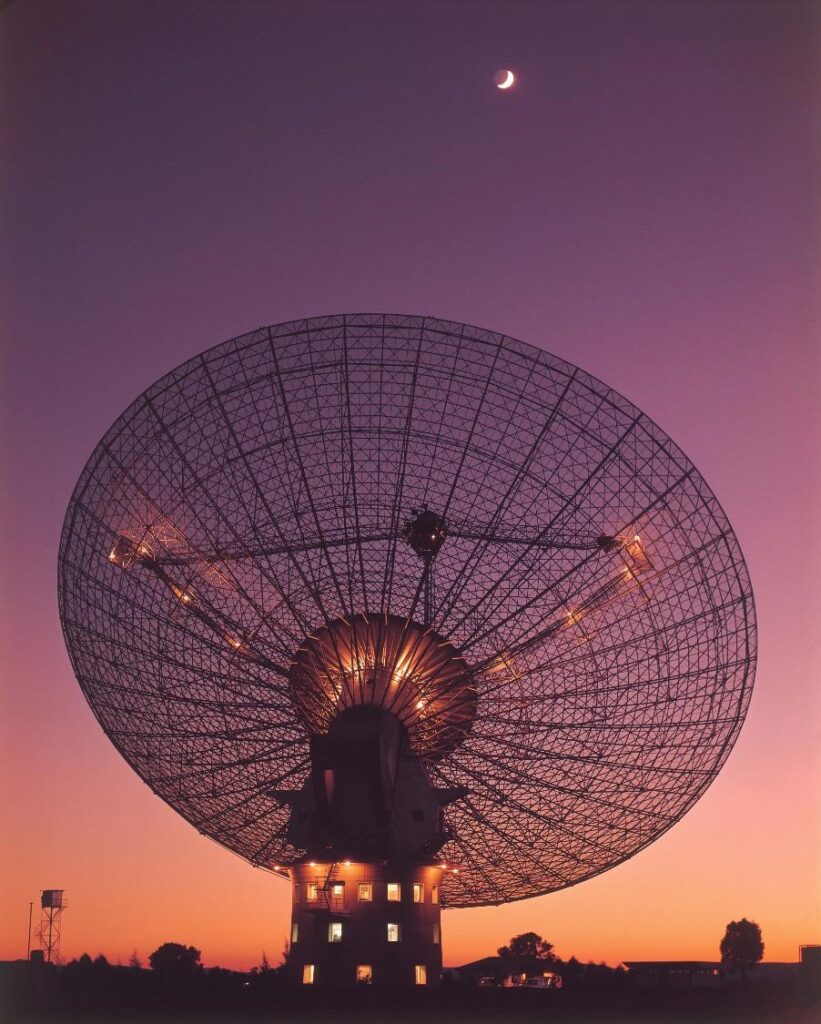

On the Apollo-11 flight plan, the lunar EVA was scheduled so that the television transmission would be received at the Goldstone DSN station, where the 210 ft “Mars” antenna would provide maximum reception capability of the relatively weak television signal. However, should the Moonwalk should occur when Goldstone was unable to receive the television signals, NASA contracted the 210 ft Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia to act as a back-up to receive the astronaut telemetry and television broadcast from the Moon. As events transpired, it was fortunate that this arrangement was in place!  The "Mars" DSN antenna at Goldstone, so called because it was developed to support space probes to Mars

The "Mars" DSN antenna at Goldstone, so called because it was developed to support space probes to Mars

Live from the Moon (via Australia)!

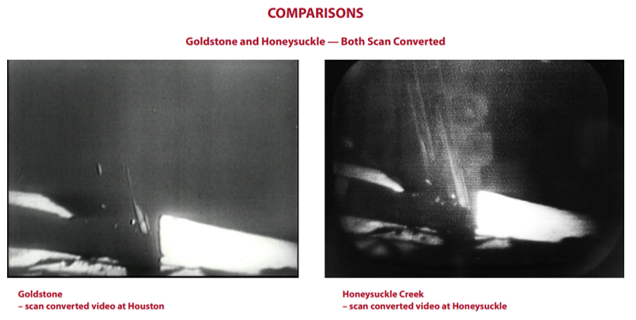

When Neil Armstrong finally backed gingerly out of the narrow LM hatch in his bulky spacesuit, he pulled a small ring to activate the television camera in the MESA. At 109:22:00 GET, the first television from the surface of the Moon was received at Goldstone. In Australia, where the Moon was just rising into their field of view, Honeysuckle Creek MSFN station (which was tracking the LM) and the Parkes Radio Telescope could also see the television transmission.

The Honeysuckle Creek antenna, near Canberra, tracking Eagle on the Moon just as Armstrong stepped onto the surface

The Honeysuckle Creek antenna, near Canberra, tracking Eagle on the Moon just as Armstrong stepped onto the surface

Although the picture quality received at Goldstone was good, the vision sent to Houston was extremely contrasty, due to incorrect settings on the scan converter that turned the slow-scan signal into one suitable for regular television broadcast. It was also initially upside down, as the camera operator forgot to flick the inversion switch. The images received at Honeysuckle Creek, though of lower resolution due to its smaller antenna, were clearer than Parkes, where the signal strength was very low. After a few moments switching between signals for the best picture, the broadcast controllers at Houston settled on the signals from Honeysuckle Creek for the initial global television transmission of Armstrong coming down the ladder and stepping onto the Moon’s surface.

About nine minutes later, when the Moon had risen high enough at Parkes to provide a much stronger signal, the quality of its images led the broadcast controllers to switch to the Parkes feed. This was used for the rest of the two-and-a-half-hour broadcast from the lunar surface.

The combined Australian and NASA team at Parkes were so dedicated to ensuring that the historic lunar television broadcast was made available to the world, that they kept the radio telescope in operation and stayed at their posts, even when a violent storm arose with windspeeds well in excess of the safe operating limit of the antenna.

“One Small Step for Man”

Moving carefully down the ladder on the leg of the LM, testing every phase of the descent to the surface, Mission Commander Neil Armstrong halted momentarily on the Eagle’s footpad to describe the lunar surface. At 109:24:15 GET, 21:56 CDT July 20 he then took Mankind’s first step onto another world, saying “That’s one small step for Man. One giant leap for Mankind”.

Armstrong about to take the First Step, as seen on the monitor at Honeysuckle Creek.

Armstrong about to take the First Step, as seen on the monitor at Honeysuckle Creek.

Armstrong had not shared with anyone what he planned to say as he stepped onto the Moon, and while his first words on the lunar surface will undoubtedly resound through history, they are, in fact, something of a non-sequitur. There’s already speculation that he may have slightly flubbed his intended line – understandable due to the stress and tension of the circumstances – and that he really meant to say “That’s one small step for a man (meaning himself). One giant leap for Mankind", which would be more logical (and indeed, later in the flight, Aldrin quoted Armstrong's utterance with the "a" included).

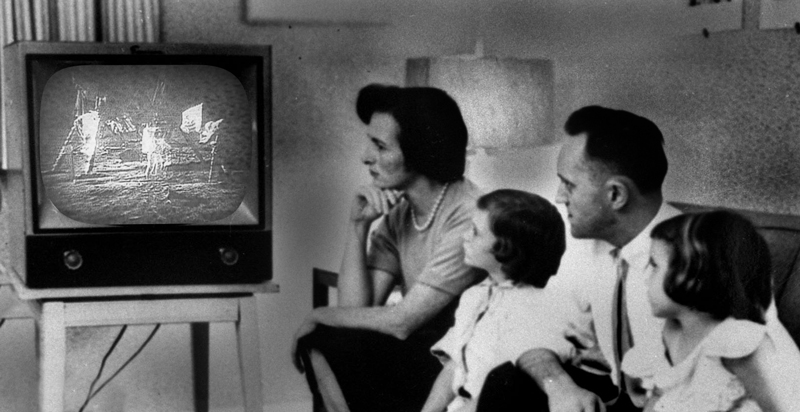

That First Step was watched around the world by an estimated 650 million viewers, potentially making it the most viewed television event in history (unless 700 million really did watch the Our World broadcast in 1967!). Millions more listened-in on the radio. There are estimates that 93% of televisions in the US were tuned the broadcast.

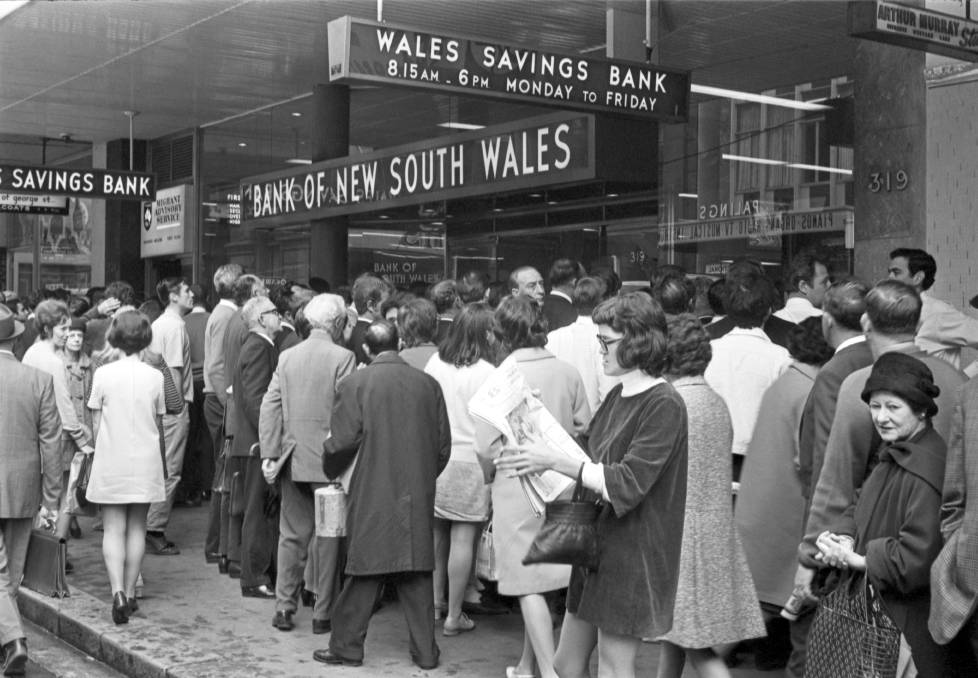

To watch the historic event, people gathered around television screens at home, or wherever they could find them. In Australia, where television ownership is still relatively low, crowds gathered around the shopfronts of any building displaying a television, like the bank shown below, since the Moonwalk occurred around lunchtime. School children spent the day in front of sets in the classroom or assembly hall. Seasoned newsmen around the world, like your famous Walter Cronkite, struggled to convey their emotions as the ancient dream of touching the Moon was realised in Armstrong's "small step".

On the Surface of the Moon

After ensuring that the Moon’s surface could bear his weight, Armstrong moved around a little, collecting a contingency sample of lunar soil – more correctly called regolith – and a couple of small rocks, in case he had to make a quick retreat to the LM. He also took a series of photographs. At least there would be something for the scientists if Eagle had to make an emergency departure! On the other side of the Moon at the time, Col. Collins was disappointed to miss the historic moment of Armstrong’s first step.

Sixteen minutes later, Col. Aldrin began backing cautiously out of Eagle’s hatch to join Armstrong, making a joke about not locking them out of the LM. On reaching the surface, an awestruck Aldrin described the vista before him as “magnificent desolation”.

As they inspected their spacecraft and their surroundings, both astronauts found their suits comfortable to walk around in, although they found it difficult to stand up again after bending down to pick up an object.

Ceremonial Activities

As a momentous historic event, the Moonwalk included several ceremonial activities, commencing with the unveiling of a small commemorative plaque, marking the place that humans first landed on the Moon, that was attached to between the third and fourth rungs of the LM ladder. At 109:52:19 GET, the two astronauts gathered around the Eagle’s ladder and ‘unveiled’ this plaque by removing its cover. Armstrong then read the inscription aloud for everyone back on Earth.

Armstrong reading the plaque, with Aldrin beside him. You can almost see the astronauts' faces!

Armstrong reading the plaque, with Aldrin beside him. You can almost see the astronauts' faces!

After this moving moment, Mr. Armstrong and Col. Aldrin removed the television camera from the MESA and set it up on a stand, so that it could view their field of operations as they went about performing the real work of their mission.

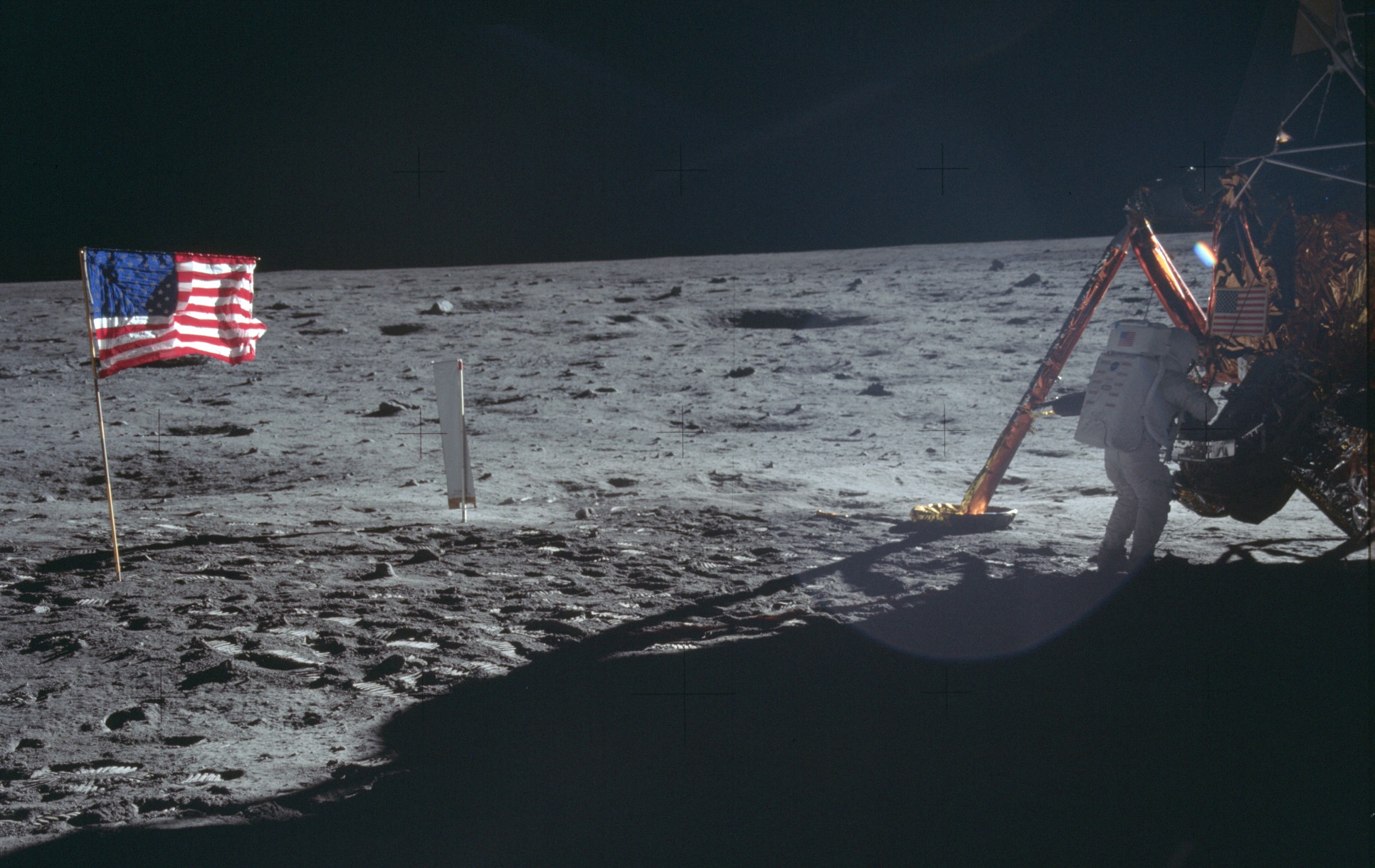

Although not listed on their procedure checklist, the astronauts' next ceremonial task was setting up a US flag, just as the polar explorers of the past have done on reaching their goals. Since the United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty, established in 1967, prohibits any nation on Earth from claiming ownership of the Moon, the US Government has been very careful to state that the flag-planting is purely symbolic, recognising the United States as the first country to land on the Moon, but not representing territorial claim.

The astronauts found it difficult to insert the flagpole into the lunar surface and had trouble extending the arm designed to stretch out the flag to its full extent on the airless lunar surface. However, this worked to good effect, creating the impression that the flag was actually waving in a breeze.

Aldrin poses with the "waving" flag

Aldrin poses with the "waving" flag

When the astronauts planted the flag on the Moon's surface, an identical flag was raised in the MOCR.

As a symbolic act of international representation, a silicon disc about the size of a 50-cent piece was placed on the Moon's surface. It contains goodwill messages in the form of statements from leaders of 73 countries around the world, although the USSR and the People's Republic of China are not included.

A final symbolic event took place a little while later, at 110:16:30 GET, when President Richard Nixon made the first interplanetary phone call from the Oval Office in the White House directly to the astronauts on the Moon. Armstrong and Aldrin stood before the television camera to receive the call, so it could be telecast as a split-screen, showing both the astronauts and President Nixon in conversation. The President praised the astronauts for their historic achievement, adding “Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of Man’s world… For one priceless moment in the whole history of Man, all the people on this Earth are truly one.”

Down to Work

After the ceremonial activities, the real work of the Apollo-11 astronauts began. Aldrin conducted experiments to determine the extent of an astronaut’s mobility, attempting to run and hop like a kangaroo. He also took a core tube sample of the regolith, although he was not able to drive a core tube far into the surface.

Two more images destined to become iconic, I'm sure. Aldrin on the lunar surface, and a close-up of the impression his boot is making in the regolith!

Two more images destined to become iconic, I'm sure. Aldrin on the lunar surface, and a close-up of the impression his boot is making in the regolith!

Mr. Armstrong carried out geological observations and collected bulk samples of rock and regolith. He took a large number of photographs of the lunar surface, from close-ups of rock structures and regolith to panoramas and views of craters.

Because Armstrong was usually carrying the camera, the majority of Apollo-11 photographs of an astronaut on the lunar surface show Col. Aldrin. The picture above is one of the rare images – as distinct from television coverage or film – of Armstrong on the lunar surface.

Because Armstrong was usually carrying the camera, the majority of Apollo-11 photographs of an astronaut on the lunar surface show Col. Aldrin. The picture above is one of the rare images – as distinct from television coverage or film – of Armstrong on the lunar surface.

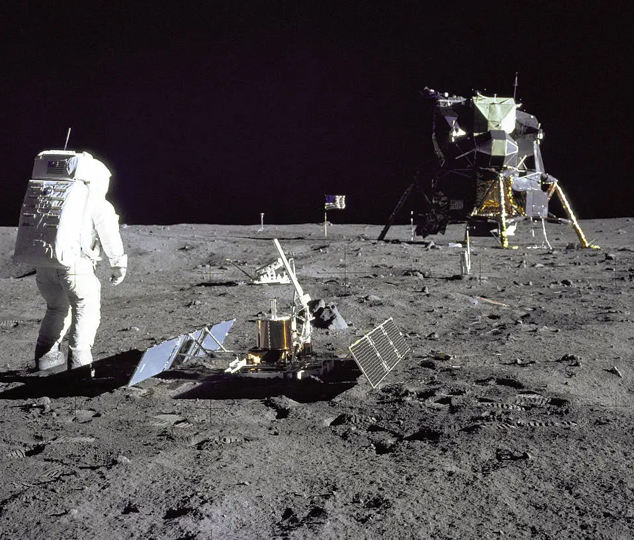

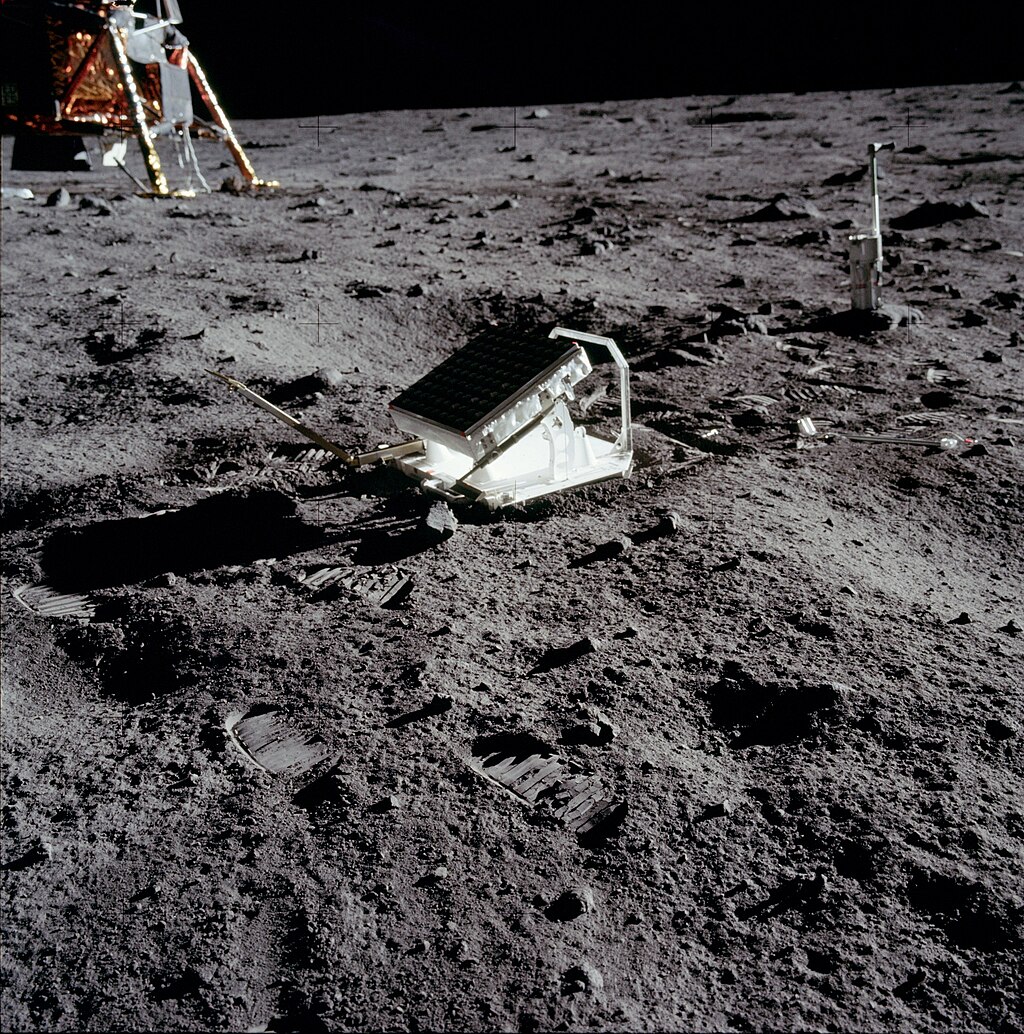

Col. Aldrin set out the EASEP (Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package), the first set of scientific instruments to be placed on the Moon. EASEP instruments include: a seismic detector to measure Moonquake activity, a laser reflector that can be targetted from Earth to precisely measure the distance between our planet and its satellite; a solar wind particle collector; and even a tiny detector to measure the characteristics of lunar dust. Tracking stations on Earth are now collecting data from these instruments to continually monitor conditions around the landing site, even though the astronauts have departed (bringing the solar wind collector sheet back with them to Earth for analysis).

Aldrin setting up the EASEP seismic detector

Aldrin setting up the EASEP seismic detector

The solar wind particle collector

The solar wind particle collector

The lunar laser ranging experiment for making precise measurements of the distance between the Earth and the Moon

The lunar laser ranging experiment for making precise measurements of the distance between the Earth and the Moon

Back to the LM

After 2 hours 31 minutes and 40 seconds, Neil Armstrong and “Buzz” Aldrin concluded their activities on the surface of the Moon, loading back into the LM some 47lbs of lunar rocks and regolith. They had taken 339 images of the lunar surface and their activities, and walked a total of 1100 yds, travelling a maximum of 67 yds from the LM. The extent of the Apollo-11 lunar excursions could be contained within a football field, but from this small beginning future missions will expand the range of their activities, exploring further away from the LM.

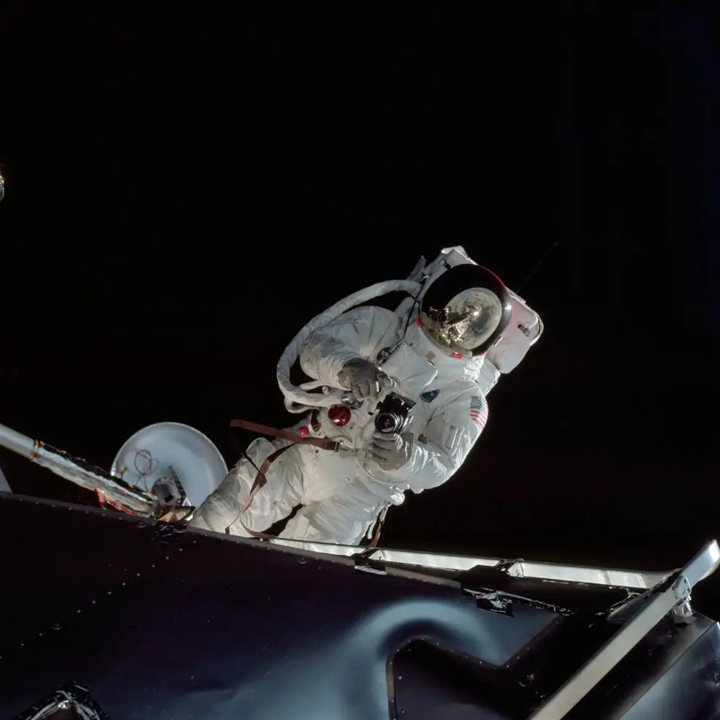

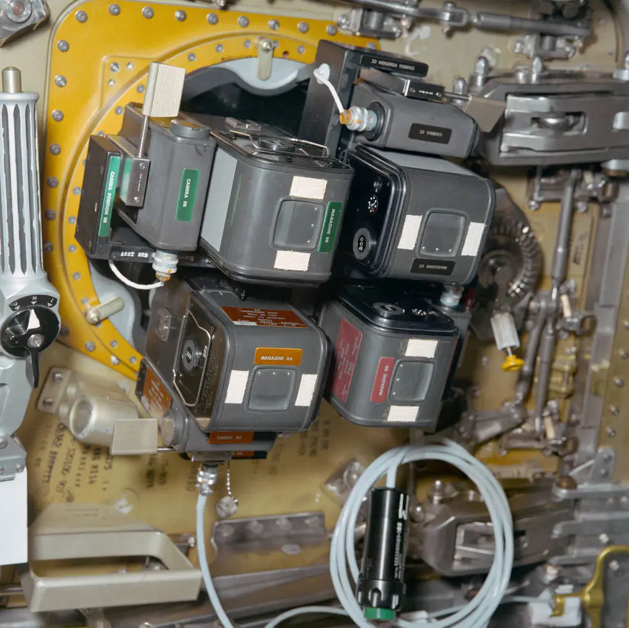

Back aboard Eagle, the astronauts’ first chore was to pressurise the cabin and begin stowing the rock boxes and film magazines. To allow for the weight of the lunar samples, the astronauts’ lunar overboots, life support backpacks, spacecraft trash, and any other gear no longer required, were jettisoned onto the Moon’s surface (proving that humans can leave litter anywhere!).

Elated but exhausted, Armstrong and Aldrin then took time to rest and get some sleep, Col. Aldrin curled up in the limited floor space of the LM, while Armstrong rigged up a sleeping place on the cover of the ascent engine. Neither of them slept well, though future lunar crews will have proper hammocks, I'm told.

After more than 21½ hours on the Moon, Mr. Armstrong and Col. Aldrin prepared their ship for lift off, firing their ascent engine just one minute behind the flight plan scheduled time at 124:22:01 GET. The blast from the engine appears to have knocked over the flagpole planted by the astronauts, but that didn’t dampen the crew’s spirits as the ascent engine worked as expected and set them on a trajectory to rendezvous with Col. Colins in Columbia!

This article has been lengthy, but there has been so much to cover with such a historic mission. I'm going to pause at this triumphant moment in the story, and will continue with a final wrap-up later this month, when we will hopefully have even more information as the lunar samples are analysed and the Apollo-11 crew are released from isolation.

![[August 4, 1969] A Small Step and a Giant Leap (Apollo-11, Part 2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Apollo-11-Aldrin-on-Moon-614x372.png)

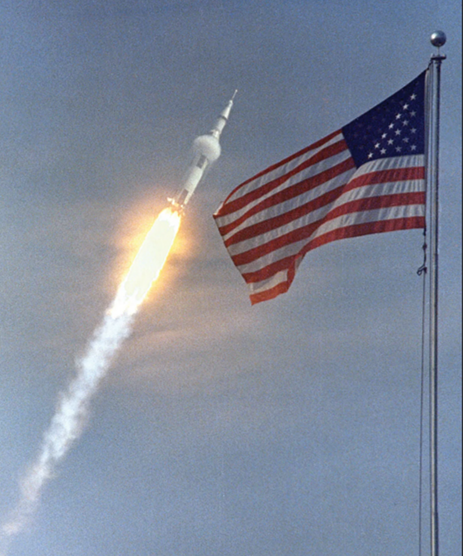

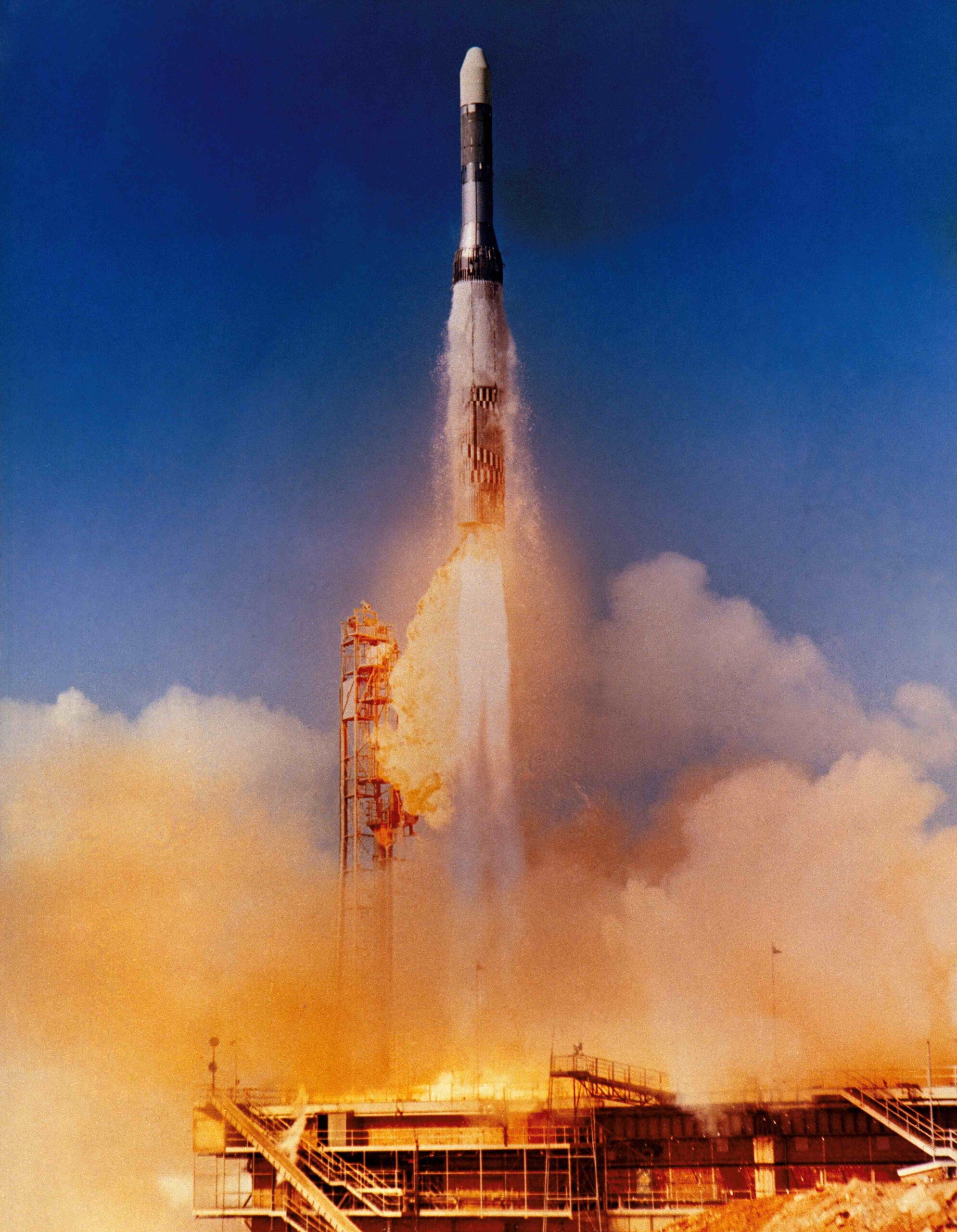

![[July 18, 1969] The Greatest Adventure Lifts Off (Apollo-11, Part 1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Apollo-11-launch-1-463x372.png)

![[May 20, 1969] Ad Astra et Infernum (June 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690520coverfsf-652x372.jpg)

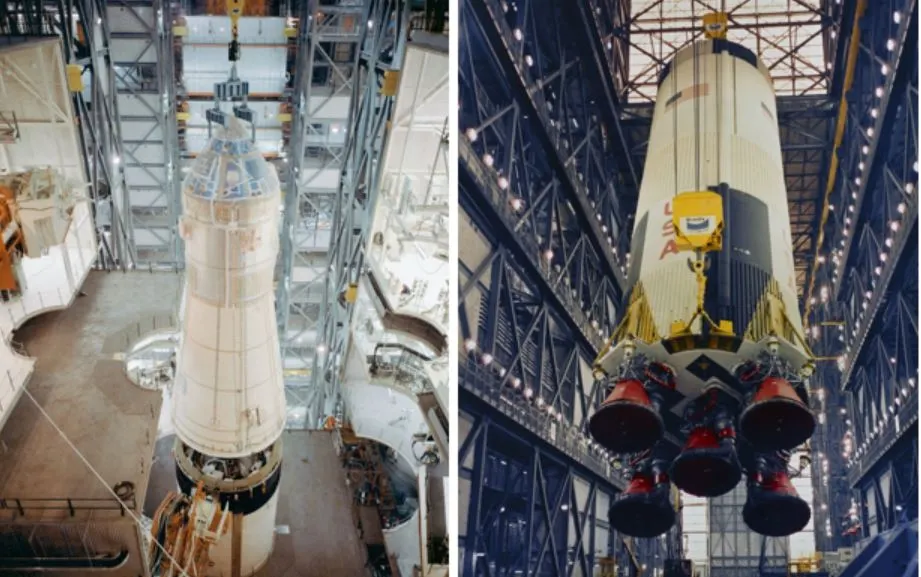

![[March 16, 1969] Flight of the Space Spider (Apollo 9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Apollo-9-Space-Spider-547x372.png)

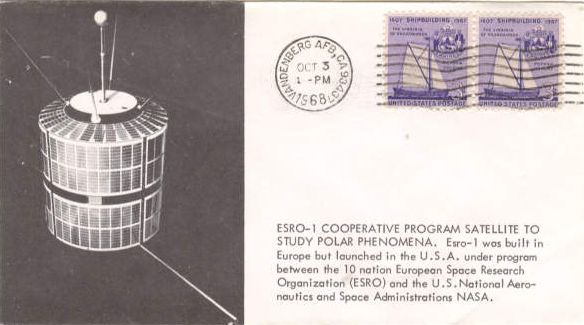

![[February 16, 1969] Triumph, Tough Luck and Turmoil (European Space Update)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ESRO-1A_cover-1-672x372.jpg)

![[January 22, 1969] NASA’s Christmas Gift to the World Part 2 (Apollo 8 continued)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Apollo-8-Earthrise-672x372.jpg)

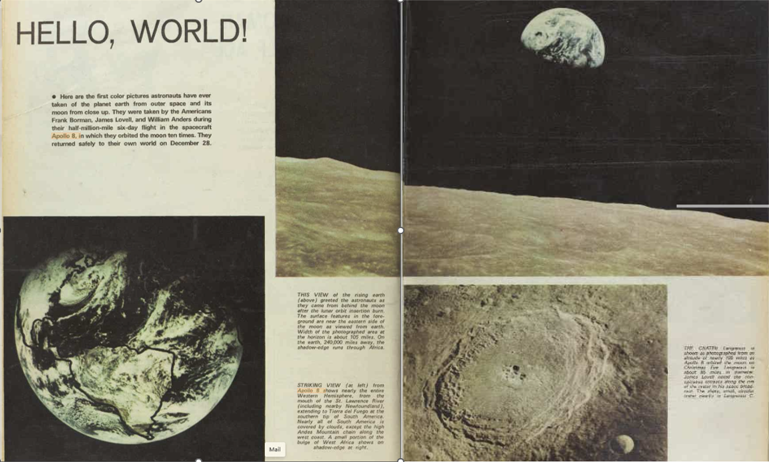

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age

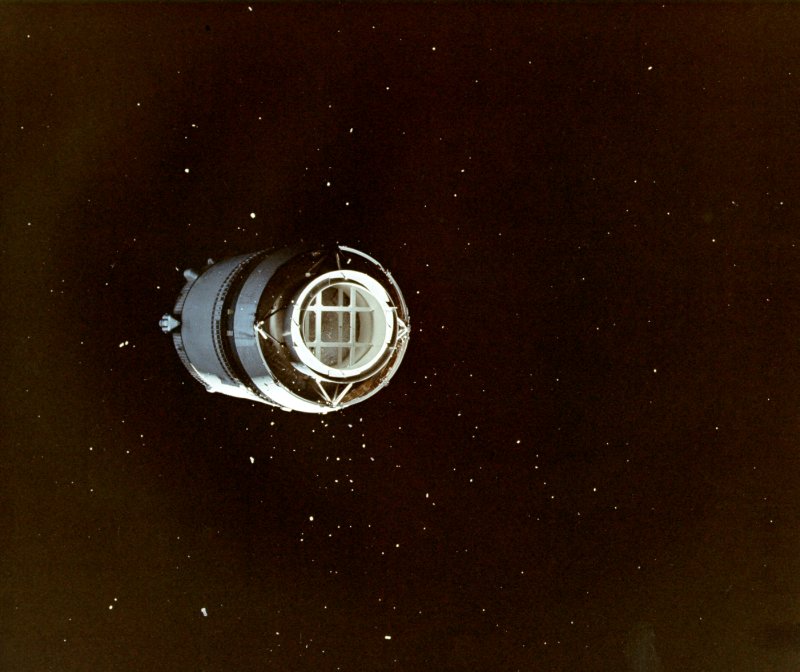

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage

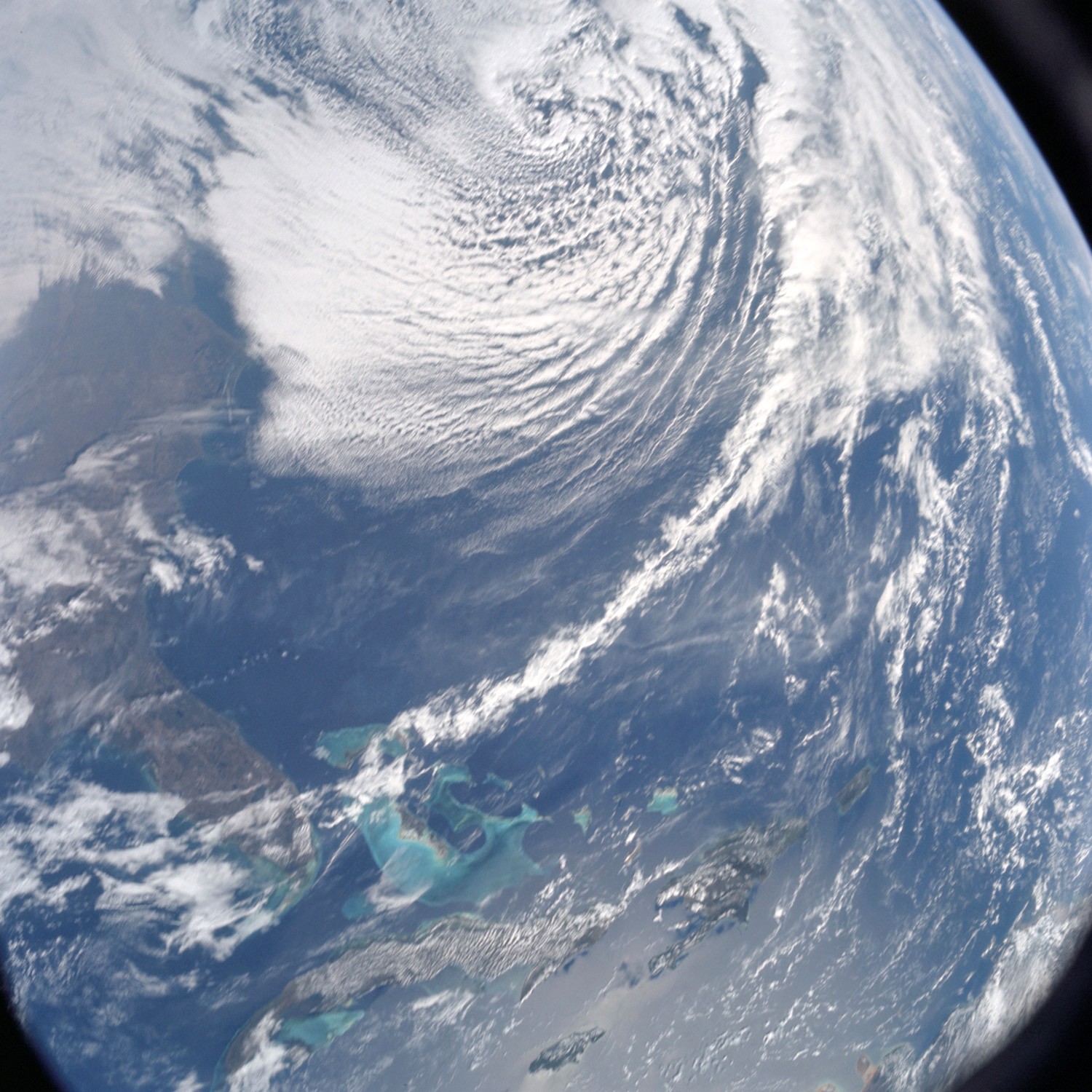

Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands

Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance!

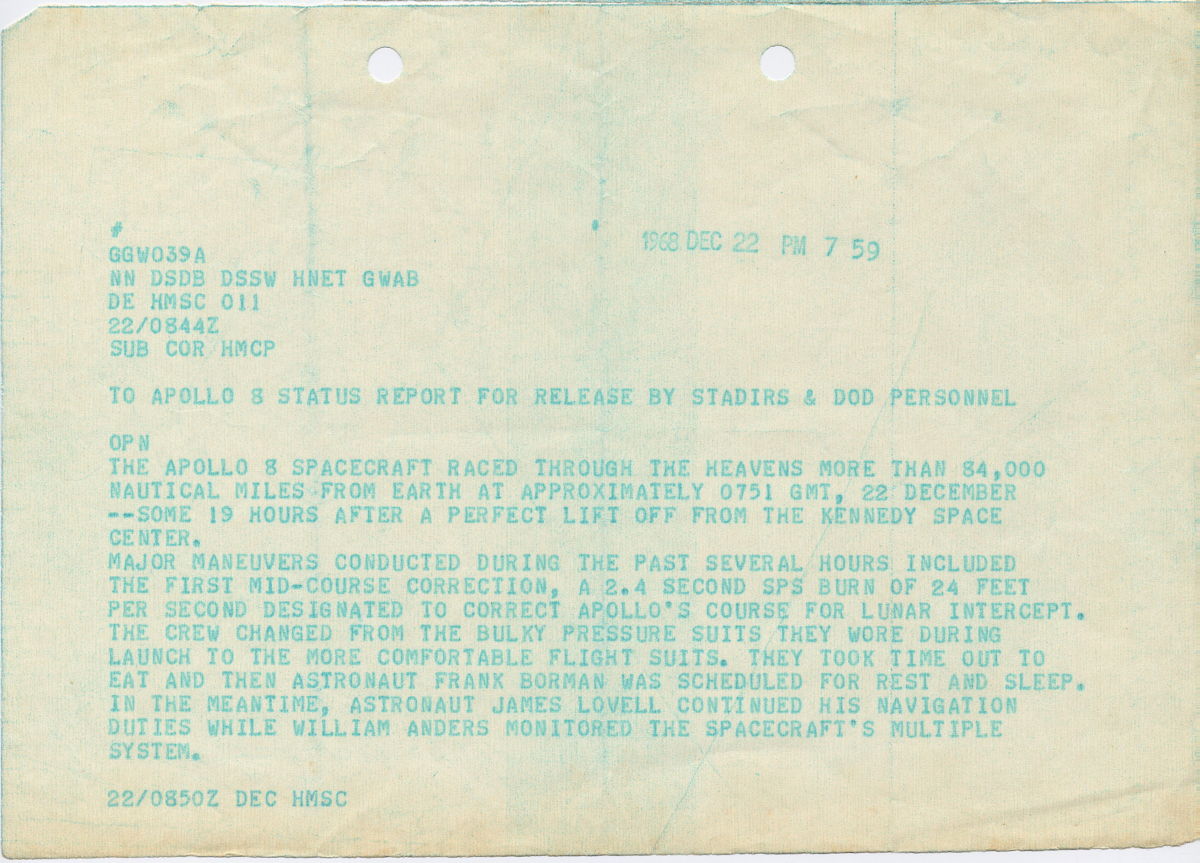

The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance! The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast

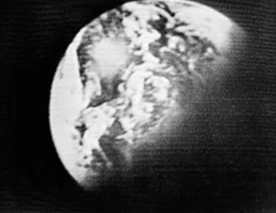

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

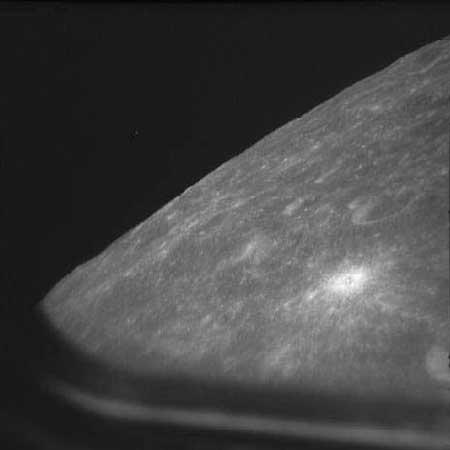

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon!

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon! View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast

View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast Awestruck, they scrambled so quicky to capture the vision that no-one is quite sure now who took which picture, although it seems that Col. Borman may have snapped the first black and white photograph, and Bill Anders a number of breathtaking colour images of the Earthrise.

Awestruck, they scrambled so quicky to capture the vision that no-one is quite sure now who took which picture, although it seems that Col. Borman may have snapped the first black and white photograph, and Bill Anders a number of breathtaking colour images of the Earthrise. Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph

Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures

This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis

A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast

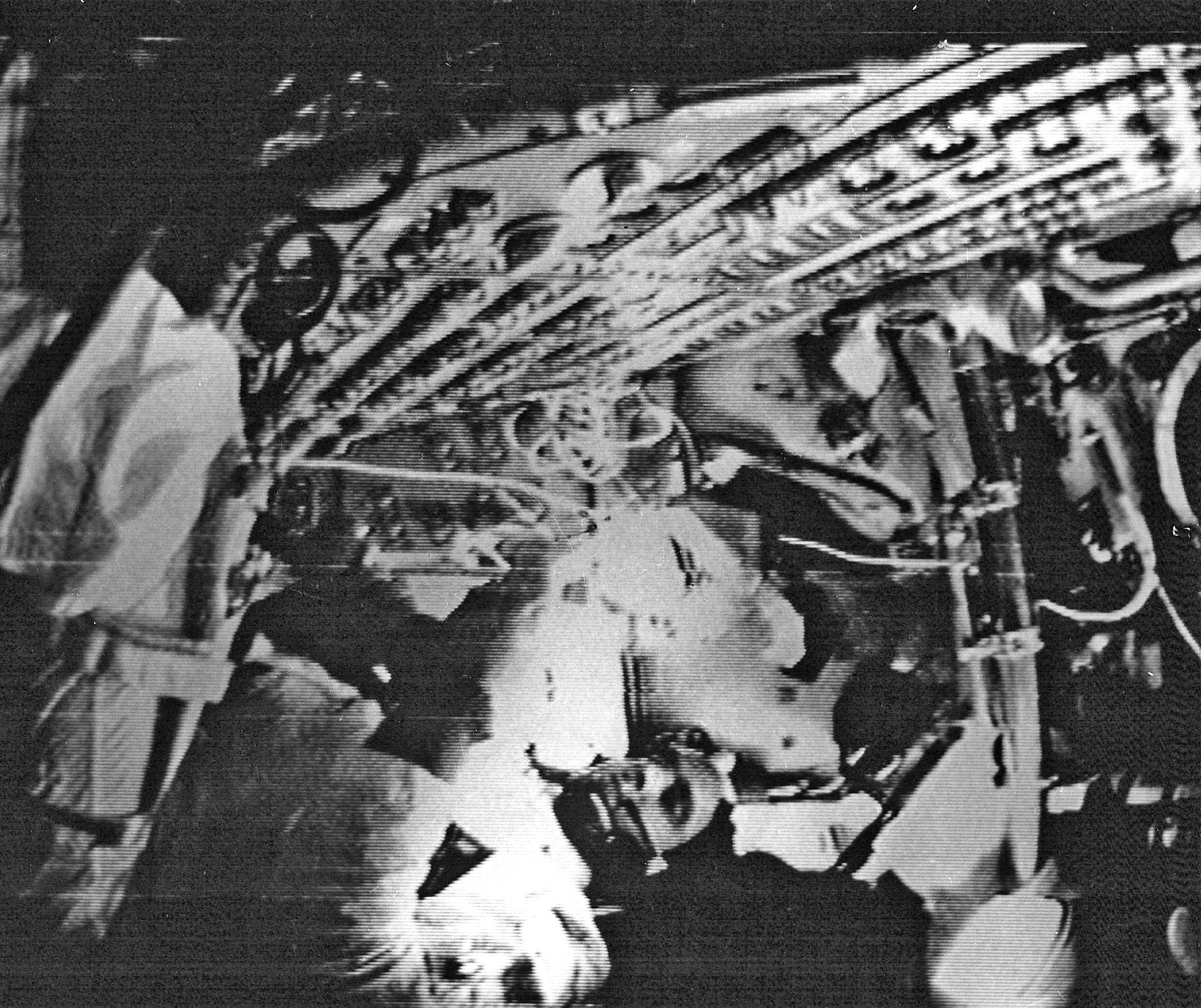

Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast

A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal

An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

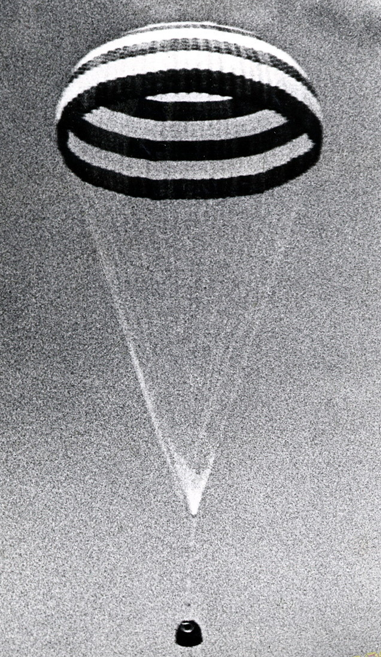

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations

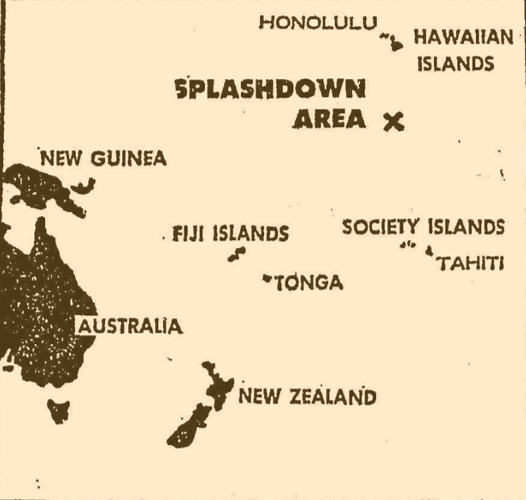

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area

Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area  After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home!

After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home! <

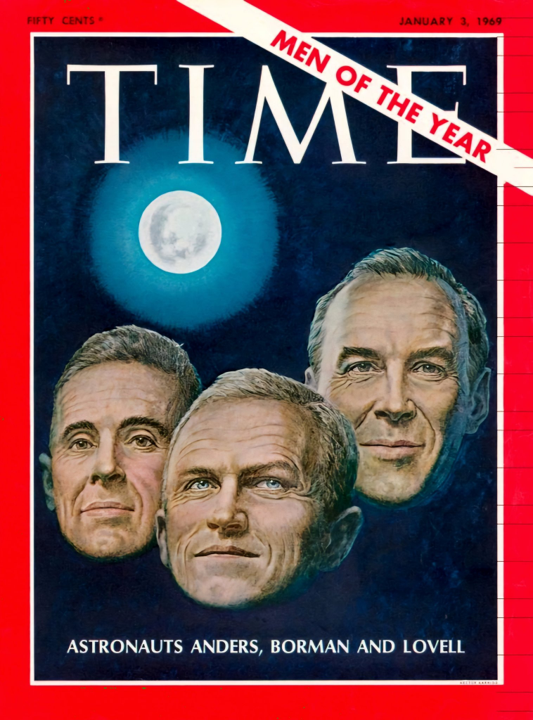

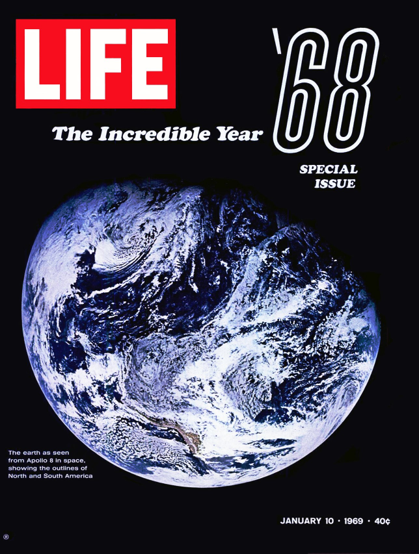

< For the influence and impact of their mission, Time magazine has chosen the crew of Apollo 8 as its Men of the Year for 1968, while Life has selected the post-TLI image of the Earth for the cover its 1968 retrospective issue.

For the influence and impact of their mission, Time magazine has chosen the crew of Apollo 8 as its Men of the Year for 1968, while Life has selected the post-TLI image of the Earth for the cover its 1968 retrospective issue.

![[December 22, 1968] What wonders await? (January 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681222cover-672x372.jpg)

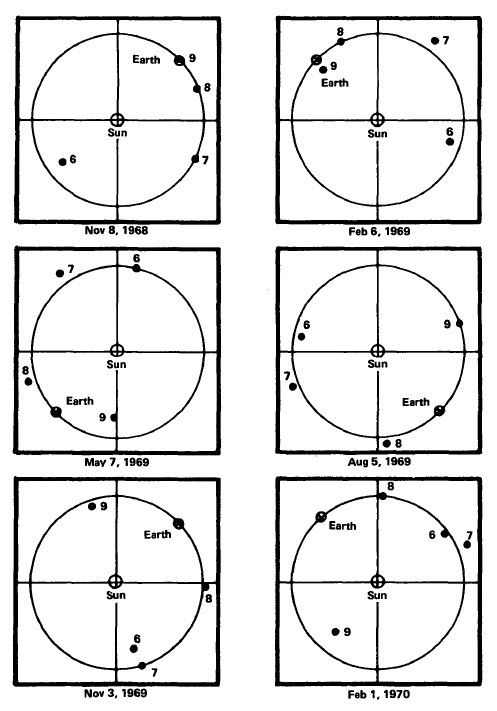

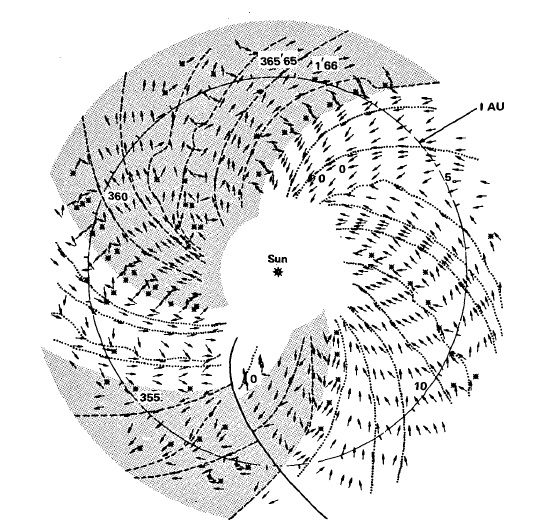

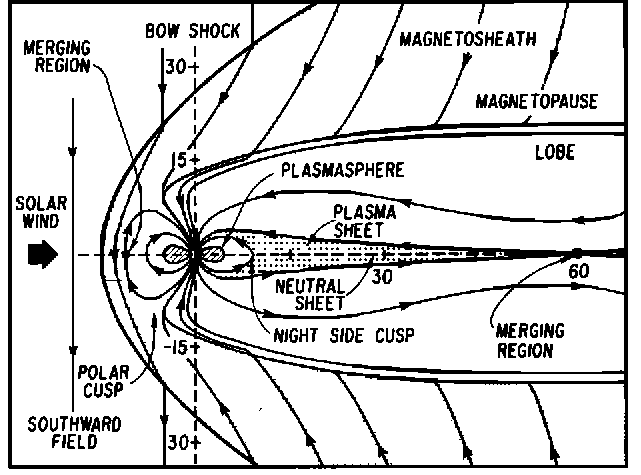

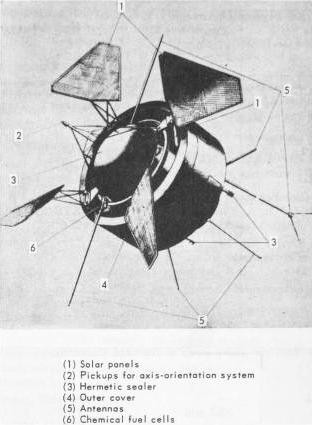

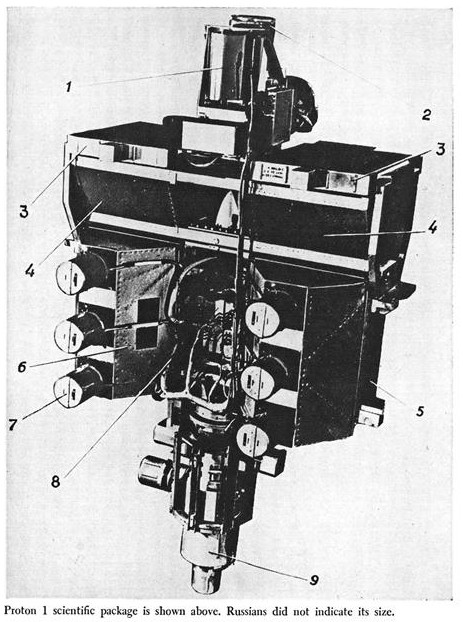

![[November 18, 1968] Pioneers and Protons (a space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681118aurora-672x372.jpg)

![[November 4, 1968] A Mysterious Mission (Soyuz-2 and 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Soyuz-3-patch.jpg)

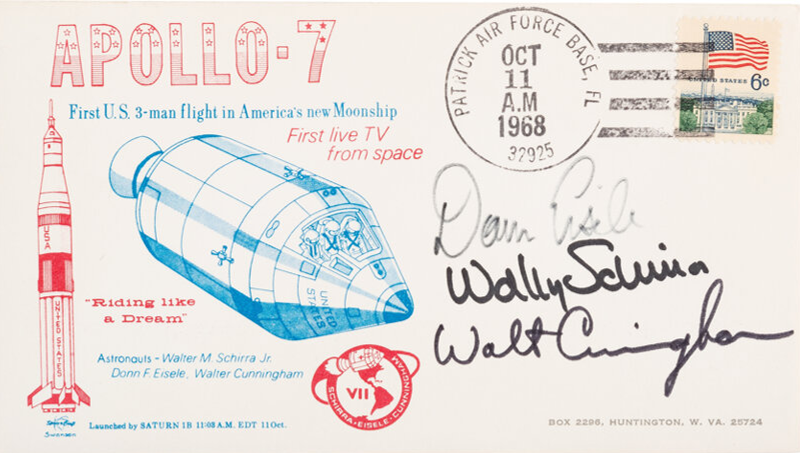

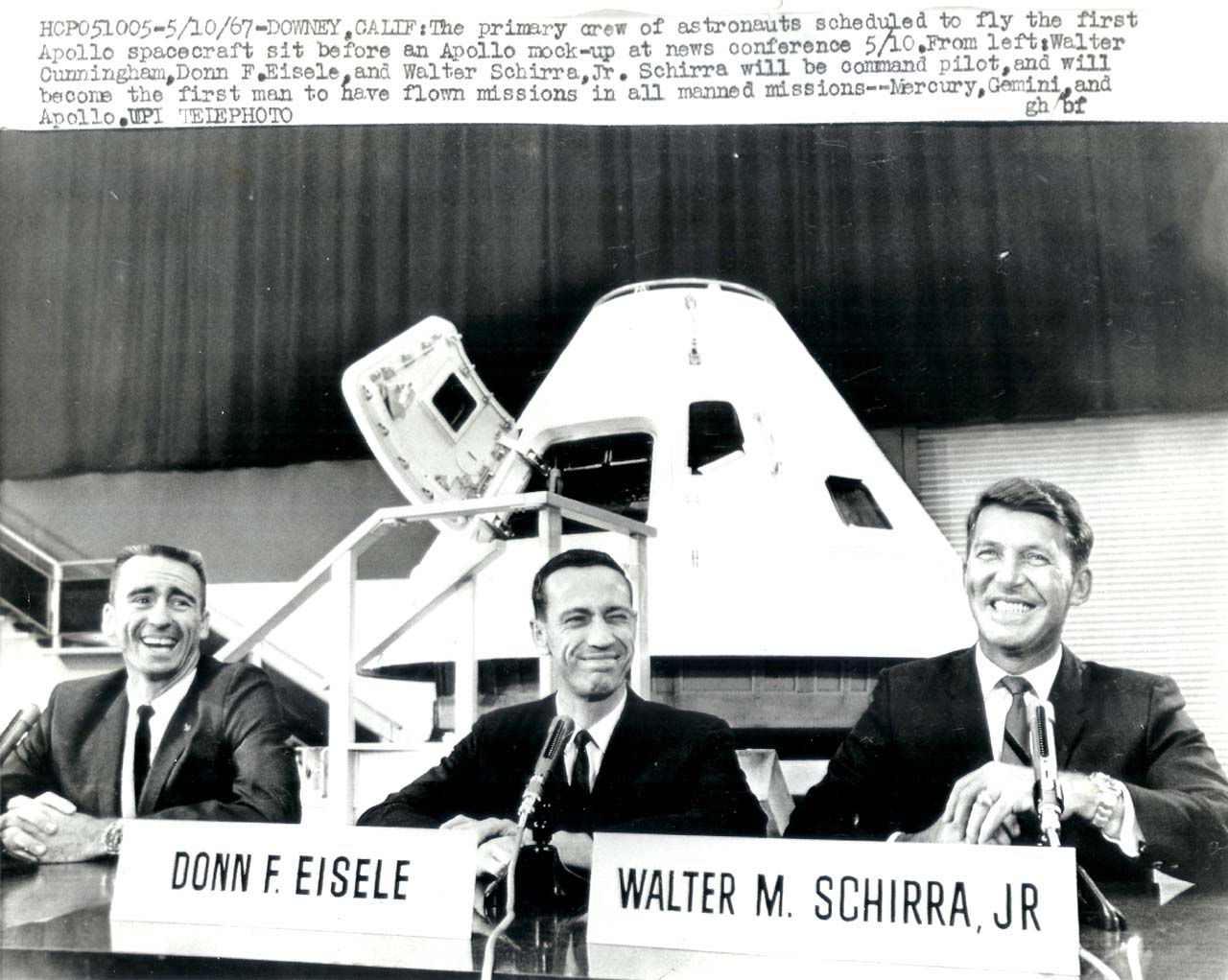

![[October 26, 1968] Phoenix from the Ashes (Apollo-7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Apollo-7-cover.jpg-672x372.png)