Don't miss tonight's Spocktacular edition of Science Fiction Theater! Starts at 7PM Pacific. Also featuring the last appearance of Chet Huntley on the Huntley/Brinkley Report!

by Gideon Marcus

Paine-ful exit

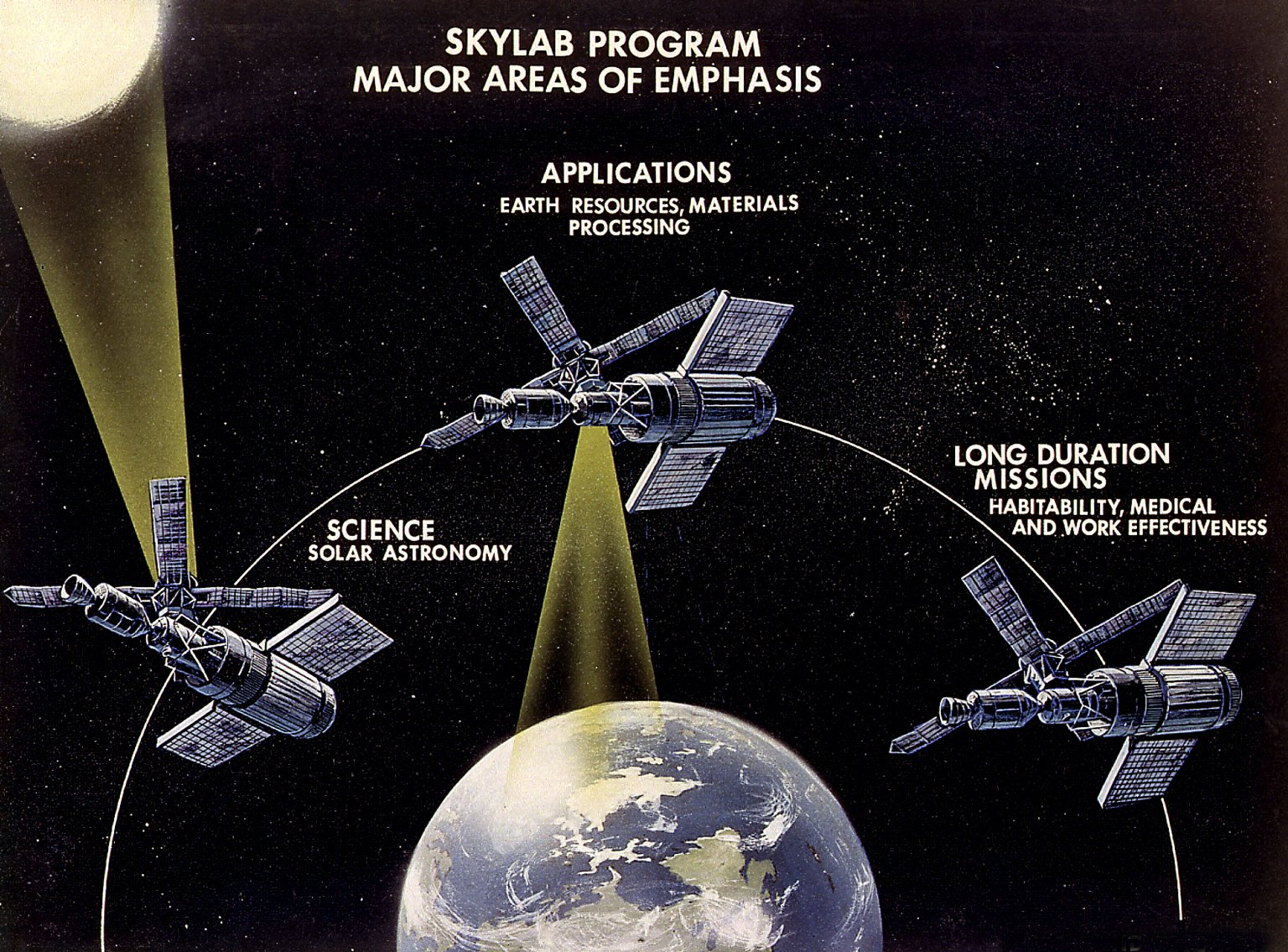

The proverbial rats are leaving the sinking ship. Not too long ago, a clutch of NASA scientists departed America's space agency, citing too much emphasis on engineering and propaganda. Now, Thomas O. Paine, who took NASA's reins from its second adminstrator, Jim Webb, has announced his resignation. He leaves the agency on September 15. He lasted less than two years; contrast with Webb, who was there seven and a half.

Paine did not characterize his departure as any indication of disagreement with the agency's current direction. He said he was leaving NASA in strong shape, and that this was the most appropriate time for his departure. He's going back to a management position with General Electrics.

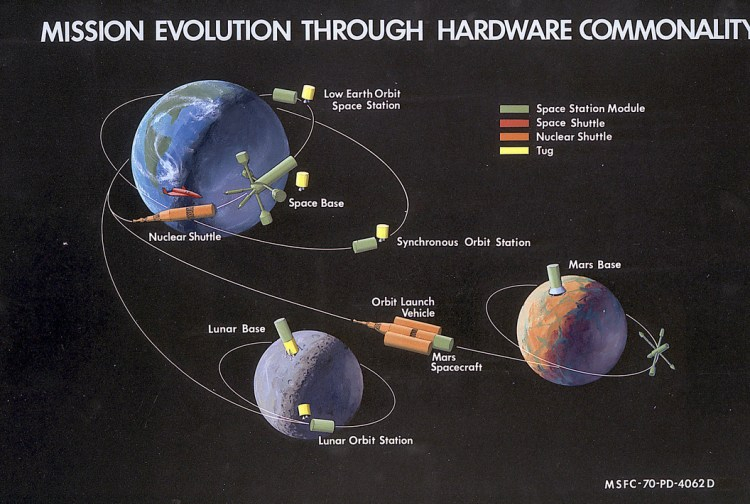

But Paine cannot be very happy with how things have been going lately. NASA's work force has been gutted–from 190,000 to 140,000 personnel; the last Saturn V first stage will be completed next month; and the future of Apollo's successor, the Space Shuttle, is in doubt. The poor director has watched the space agency go from the pinnacle of human achievement to a nadir unseen since the late '50s. If only we'd adopted the Agnew "Mars Plan"…

Deputy Administator George M. Low will take Paine's place for the time being. A replacement has not yet been tapped. Stay tuned!

Painful effort

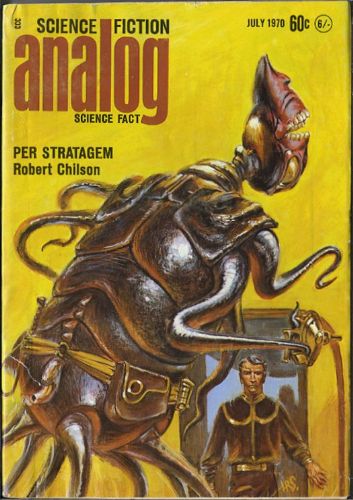

If Paine left willingly, Analog editor John Campbell, on the other hand, seems determined not to let his magazine go until he does. Which is sad because this month's issue is yet another indication of how far the once-proud property has fallen in quality."Two astronauts meet one another between a large satelite.

Cover by Kelly Freas

Continue reading [July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 Analog)

![[July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

![[June 20, 1970] Gemini Too (the two-week flight of <i>Soyuz 9</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700620launch-443x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

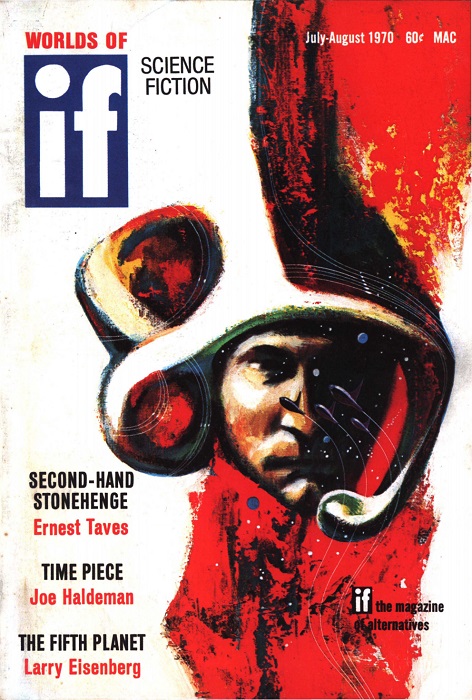

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[May 26, 1970] A Regrettable Case of Runaway Apophenia (Erich von Däniken's <i>Memories of the Future</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Image-1-672x372.jpg)

![[April 26, 1970] Red stars in space (Communist China and the USSR make leaps)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700426dongfanghong1-672x372.jpg)

![[April 22, 1970] “Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!” (Apollo-13 emergency in space)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Apollo-13-13-672x372.jpg)

![[March 30, 1970] The Age of Explorer — the end of the Space Race](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700331nixon-672x372.jpg)

![[March 20, 1970] Here comes the sun (April 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700320fsfcover-651x372.jpg)