by Gideon Marcus

Rime of the Recent Mariner

I always cast about the news for tidbits to head my articles. After all, when people read my writings, say, a half-century hence, I want them to be appreciated in the context in which they were created. Creations, and critique of those creations, cannot stand in isolation (or so I believe).

But, wow, how many times can I talk about the latest protest/riot (six killed in Atlanta last week), or Cambodia (Admiral Moorer recently assured us that the reason we can't destroy the mobile NVA base is…because it's mobile; but we did liberate 387 tons of ammunition, 125 tons of prophylactics, and 83 tons of Communist finger puppets so the Search & Destroy mission was absolutely a success), or the Warm War going on in the Middle East (2 Egyptian Mig-21s shot down the other day, 2 Syrian Mig-17s the day before, but the Israelis absolutely did not lose an F-4 over Lebanon) before it all sounds the same? Even Governor Reagan's latest escapades into cost effectiveness and court stacking are old hat.

This iteration of Bull Wright instills less confidence than Dan Rowan's…

To heck with it. Today, I'm going to stick with news in my bailiwick, and nifty news to boot.

You folks surely remember Mariners 6 and 7, twin probes sent past Mars last year, returning unprecedented information and photos from The Red Planet. Well, even now, both probes are contributing to science, long past their original mission.

JPL astronomer Dr. John D. Anderson and Cal Tech astronomer Dr. Duane O. Muhleman are using the two spacecraft to test the validity of Einstein's theory of relativity. Per Einstein, the velocity of light slows in the presence of a gravitational field. If that's the case, then the signals from the Mariners, as they pass the Sun, should decrease—slightly, but measurably.

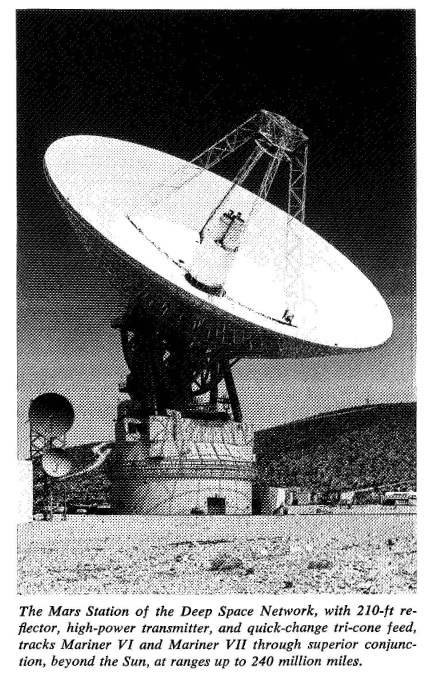

To measure this, the two scientists had to wait until Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 passed behind the Sun with respect to the Earth. For the former, this happened on April 30; for the latter, May 10. The precise distance-measuring system the two scientisits built in the Mohave Desert should register a slow-up of 200 millionths of a second in the spacecrafts' round trip signal.

This confirmation, should it be reported, will help put paid efforts by other scientists who say that Einstein's theories are wrong or inaccurate, by as much as 7% according to Princeton's Dr. Robert H. Dicke, who needs that to be the case for his theory of Mercury's curious orbital eccentricities.

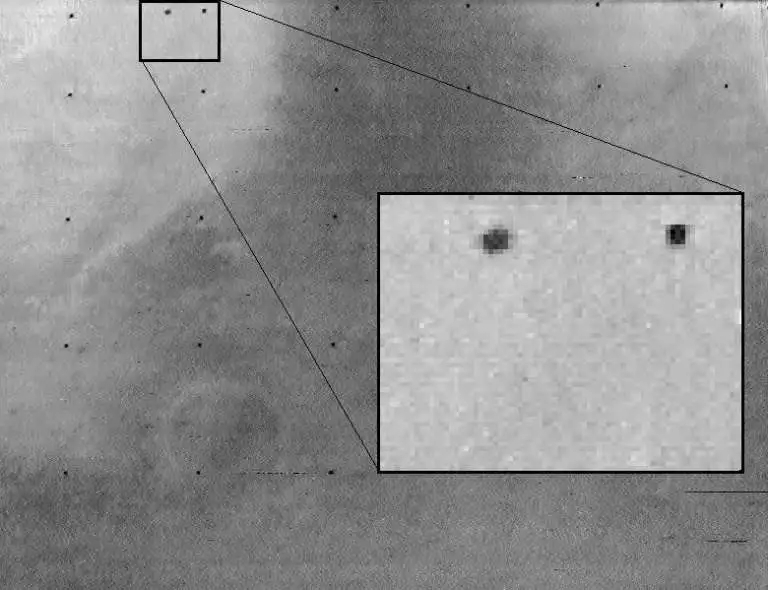

In other Mariner news, New Mexico State Univ. astronomer and Mariner project scientist Bradford A. Smith has some neato news about Phobos, the larger of Mars' moons. Mariner 7 snapped a picture of the little rock at a distance of 86,000 miles. JPL photo-enhancement techniques indicated that Phobos was nonspherical and was larger and had a darker surface than previously thought. It's just 11.2 by 13.7 miles in dimension, elongated along the orbital plane. Its average visual geometric albedo is just 0.065, lower than that known for any other body in the solar system.

With its weird shape and composition, all signs point to Phobos not being a sister or daughter of its parent planet, but rather, probably a captured asteroid.

The issue at hand

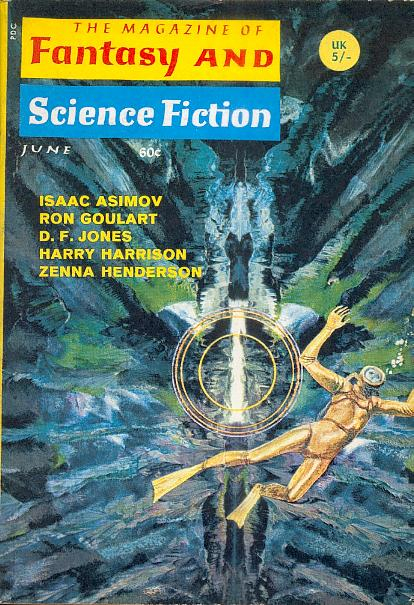

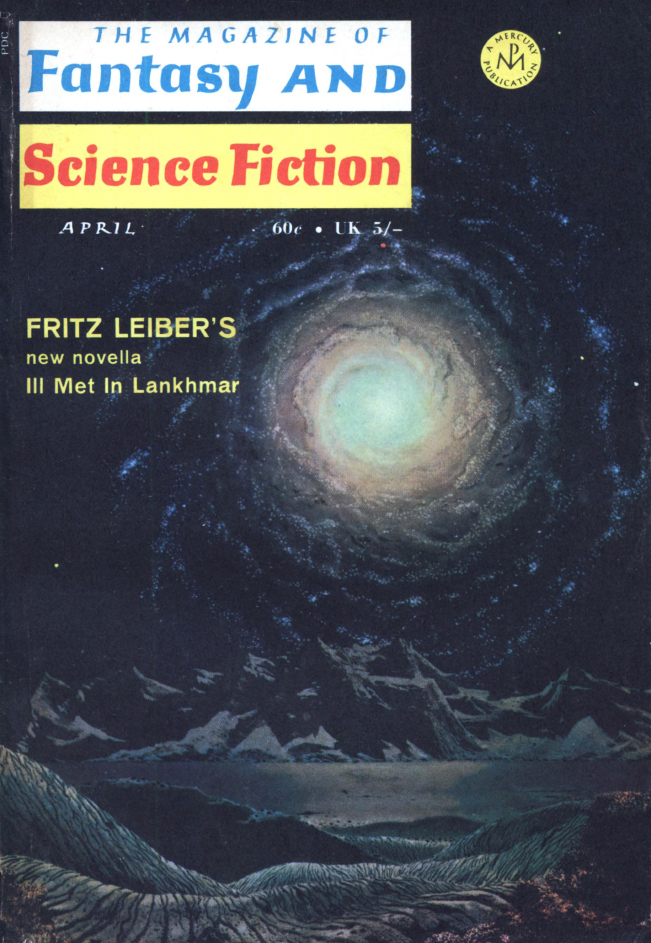

In a happy, elevated mood, now let us turn to the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction—after all, it doesn't do to review stories on an empty soul.

cover by Jack Gaughan illustrating

![[March 20, 1970] Here comes the sun (April 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700320fsfcover-651x372.jpg)

![[August 8, 1969] Two by Four (Mariners 6 and 7 go to Mars)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690808approach6-672x372.jpg)