by Victoria Silverwolf

Machine Language

Two events occurred today that demonstrate how computers can communicate with each other and with people.

At the University of California in Los Angeles, a gizmo called an Interface Message Processor (IMP) allowed two computers on campus to have a conversation, of sorts. (I assume it was something like beep boop beep.) Plans are underway to set up another IMP at Stanford University, so the two institutes of higher education can share data. One can imagine computers all over the planet chatting away, plotting to take over the world . . . well, maybe not that.

The thing that lets computers exchange information. Don't ask me how it works.

The same day, a device replacing your friendly neighborhood teller appeared at a branch of the Chemical Bank in Rockville Centre, New York. Apparently it can take your money, give you back your money, etc. Is it just me, or does Chemical Bank seem like a weird name for a financial institution? Not to mention the fact that the city doesn't know how to spell center.

Possibly depositing some of the money his company makes from the robot teller.

Fittingly, the latest issue of Fantastic features machines and other things besides humans who are capable of communicating, and performing other activities that demonstrate intelligence.

Cover art by Johnny Bruck.

As usual these days, the cover image comes from a German publication. It's not Perry Rhodan for a change.

Translated, this says The Ring Around the Sun. This seems to be a version of Gallun's 1950 story A Step Further Out, with additional material from German writer Clark Darlton, one of the folks behind Perry Rhodan.

Editorial, by Ted White

The new editor talks about the cancellation of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour because of material CBS considered offensive. He goes on to discuss the hypocrisy of some members of the older generation, and how science fiction and fantasy might help bridge the gap between young folks and their elders. Pretty serious stuff. He also admits that Fantastic is less popular than its sister publication Amazing, and promises to do something about that.

No rating.

It Could Be Anywhere, by Ted White

Maybe printing his own fiction is part of the editor's plan to improve sales of the magazine.

Illustrations by Michael Hinge.

The author spends half a page explaining the provenance of this story. He was inspired by Keith Laumer's story It Could Be Anything (Amazing, January 1963.) Note the similar title. My esteemed colleague John Boston gave this work a full five stars.

At first, White's tribute took the form of a novel called The Jewels of Elsewhen a couple of years ago. The Noble Editor gave that book four stars. Will this latest variation on a theme reach the same exalted level as its predecessors?

When the familiar becomes unfamiliar.

The narrator is a big guy who works as a private detective. After a very long day, he tries to ride home on the subway in the wee hours of the morning. A wino falls out of his seat. When the gumshoe tries to help the fellow, he finds out that he's not really a genuine human being, but some kind of lifeless simulation.

The only other real person on the subway is a young woman. (In the tradition of popular fiction, she's always called a girl.) When they get off the subway, they find out that the entire city is fake, just a bunch of empty buildings.

The premise reminds me a bit of Fritz Leiber's short novel You're All Alone, in which almost all people are mindless automatons. There's an explanation, of sorts, for what's going on. The characters are interesting, even if they are mostly passive observers of the situation. The way in which the woman's ring plays a role in the plot struck me as arbitrary.

Three stars.

A Guide to the City, by Lin Carter

This was a big surprise. I expect Carter to offer very old-fashioned sword-and-sorcery yarns or equally outdated space operas. Who knew that he could venture into territory explored by Jorge Luis Borges or Franz Kafka?

The story takes the form of an article. The author lives in a gigantic, possibly infinite, city. A single neighborhood takes up hundreds of thousands of blocks. Traveling such a distance is the stuff of legends. The author explains why mapping the entire city is impossible.

This is not a piece for those who demand much in the way of plot or characters. It's all concept, an intellectual exploration of an abstract, mathematical premise. I enjoyed it pretty well; others may find nothing of interest in it.

Three stars.

Ten Percent of Glory, by Verge Foray

In the afterlife, people continue to exist based on how living folks remember them. George Washington can expect to be part of the collective memory for a very long time; Millard Fillmore, maybe not.

The main character is an agent of sorts, who collects a percentage of the renown of his clients in exchange for promoting them in various ways. The plot involves the motives of his secretary.

Stuck somewhat between whimsy and satire, this odd little tale winds up with an ending that may raise some eyebrows. I'm still not quite sure what I thought of it.

Three stars.

Man Swings SF, by Richard A. Lupoff

This is a broad spoof of New Wave science fiction. It starts with an introduction by the fictional Blodwen Blenheim, which alternates lyrics from songs performed by Tiny Tim with a rhapsodizing about an exciting new form of speculative fiction coming from the Isle of Man.

After this, we get a story called In the Kitchen by the imaginary author Ova Hamlet. Like a lot of New Wave SF, it's hard to describe the plot. Suffice to say that it's full of outrageous metaphors and features a doomed protagonist. The piece ends with a mock biography and a ersatz critique of Ova Hamlet.

The (real) author is able to write convincingly in the style of some of the things found in New Worlds, with tongue firmly in cheek. Amusing enough, even if it goes on a little too long for an extended joke.

Three stars.

A Modest Manifesto, by Terry Carr

This essay, reprinted in the magazine's Fantasy Fandom section, originally appeared in the fanzine Warhoon. It wanders all over the place, but for the most part it deals with what the author sees as a cultural revolution, both in fantasy and science fiction and in the outside world. Food for thought.

Three stars.

So much for the new stuff. Let's turn to the reprints.

Secret of the Serpent, by Don Wilcox

This wild yarn first appeared in the January 1948 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

As I noted at the start of this article, we're going to run into a lot of entities that have as much sentience as human beings. Would you believe that this one is a gigantic people-eating serpent?

Illustration by Jones also.

Let me back up a little. The serpent used to be an ordinary guy, until he wound up on what the author calls a space island. If that means something other than a planet, it escapes me.

He encounters a huge two-headed cat (don't look at me, I don't make up this stuff) who used to be a woman. The place is also inhabited by a bunch of pygmies, who used to be people living on Mars. Not to mention some Mad Scientists. Or the guy who is a giant skull on a small body.

Very long and complex story short, the formerly human serpent gets partly changed back, and he becomes a serpent with human arms and legs. Somebody wants to turn him into a skeleton for a museum. There's a revolution by the enslaved pygmies against the Mad Scientists. A lot more stuff happens.

I hope I have managed to convey the fact that this is a crazy story. Plot logic is thrown out the window in favor of action, action, and more action. The only explanation for the weird transformations? The water on the space island does it.

Nutty enough to hold the reader's attention for a while, but at full novella length the novelty soon wears off. I got the feeling the author was pulling my leg at times, but there's not enough humor to make the story a parody.

Two stars.

All Flesh is Brass, by Milton Lesser

The August 1952 issue of Fantastic Adventures supplies this grim tale.

Cover art by Walter Popp.

The Soviet Union has conquered Western Europe, and is now attacking the United States via Canada. The story takes the form of the diary of a soldier. He learns that some dead fighters are being replaced by robotic duplicates, who not only copy their bodies but also their minds.

Illustration by Ed Emshwiller.

The replacements don't even know that they're not human, until that fact becomes obvious in one way or another. They are also designed to be eliminated within a couple of years after they're activated. Let's just say that the situation doesn't work out well.

In addition to the plot, the story paints a vivid and realistic portrait of warfare, as seen by an ordinary soldier. I was particularly impressed by the way the author handles the subplot concerning the female fighter encountered by the main character. I wasn't expecting that to go in the direction it did.

Four stars.

According to You . . ., by Ted White, etc.

After an extended absence, the letter column returns. I wouldn't bother to mention it, but it's odd in a couple of ways. First up is a mock letter from Blodwhen Blenheim and Ova Hamlet (remember them?) thanking the editor for printing Hamlet's story. A cute extension of the joke.

Next are a couple of letters asking for more sword-and-sorcery stories. One reader includes a poem about Conan. I probably shouldn't say anything about the quality of the verse.

Last is a missive attacking just about everything in the April issue. The writer, if he's real, is in jail. Hmm.

No rating.

Isolationist, by Mack Reynolds

This ironic yarn comes from the April 1950 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones again.

The narrator is a cynical old farmer, suspicious of technology and of the modern world in general. When an alien spaceship lands in his field, he thinks it's an American vessel of some sort.

Illustration by Julian S. Krupa.

The accents of the friendly inhabitants convince him they're foreigners, which makes them even less welcome than before. Not to mention that they ruined part of his crop of corn.

This is a very simple story, with an inevitable conclusion. The crotchety narrator is a decent creation, but there's not much else to it.

Two stars.

The Unthinking Destroyer, by Rog Phillips

The December 1948 issue of Amazing Stories offers this philosophical tale.

Cover art by Harold W. McCauley.

Two guys talk about the possibility of intelligent life being unrecognizable by human beings. (Back to the theme with which I started this article.) In alternating sections of text, two beings discuss abstract concepts.

Illustration by Bill Terry.

It took me a while to get the point of this story. It might be seen as a rather silly joke, or as something a bit more meaningful.

Two stars.

Fantasy Books, by Fritz Leiber and Francis Lanthrop

Leiber offers mixed reviews of a collection and a novel. Lanthrop praises three books by Leiber about the adventures of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

No rating.

Worth Talking About?

This was a middle-of-the-road issue, with everything hovering around a three-star rating. Not a waste of time, but not particularly memorable either. Maybe someday a computer will be able to read it to you, so you don't have to turn the pages of the magazine.

The Parametric Artificial Talker (PAT), developed by the University of Edinburgh in 1956, was the first machine to synthesize human speech.

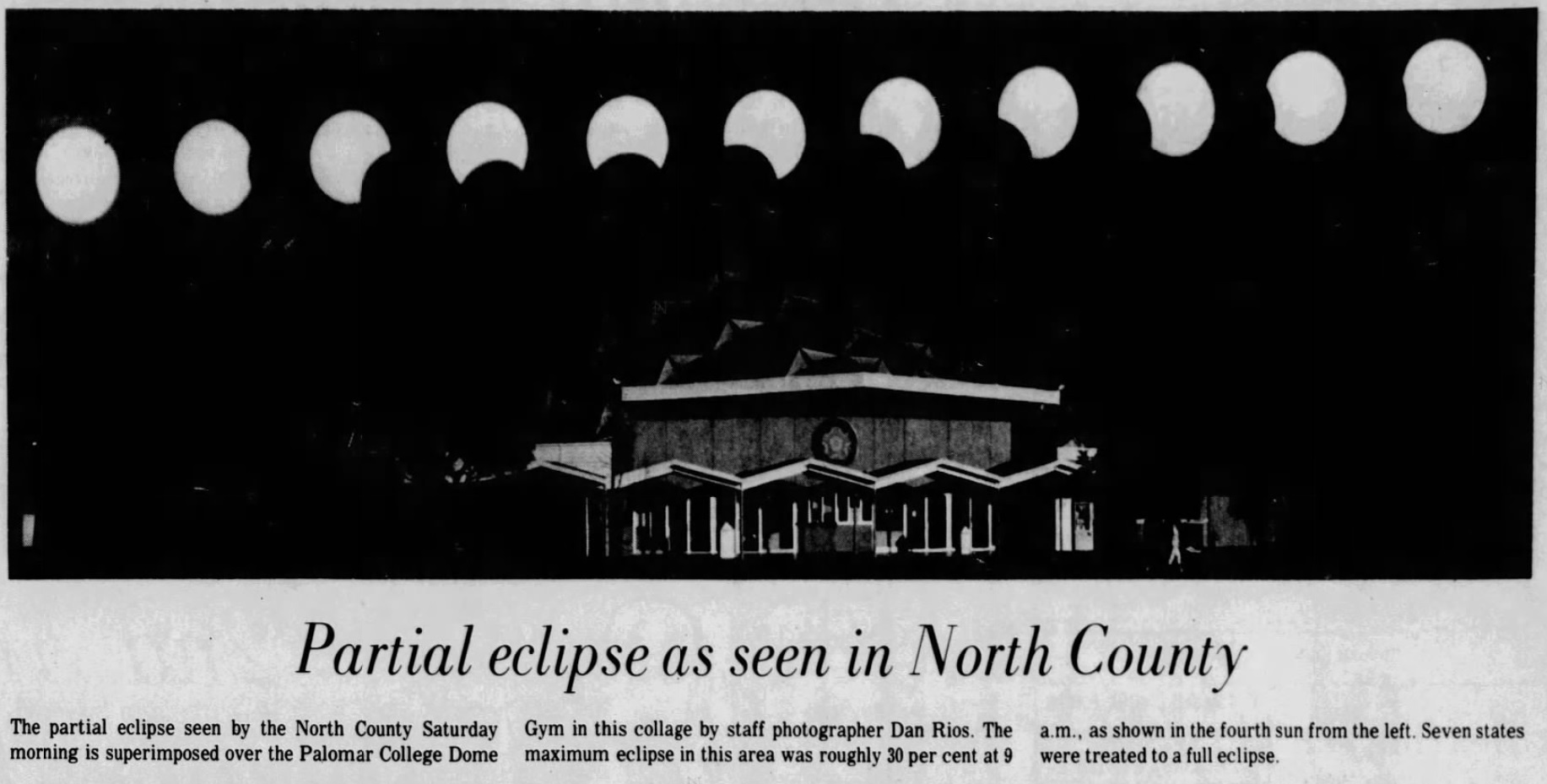

![[March 20, 1970] Here comes the sun (April 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700320fsfcover-651x372.jpg)

![[September 2, 1969] People, Machines, and Other Thinking Entities (October 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)