by John Boston

The Sublime Don’t Work Here No More

. . . Not that it showed up very often when it did. But the previous issue, which at last attained the status of “not bad,” raised hopes, now dashed again.

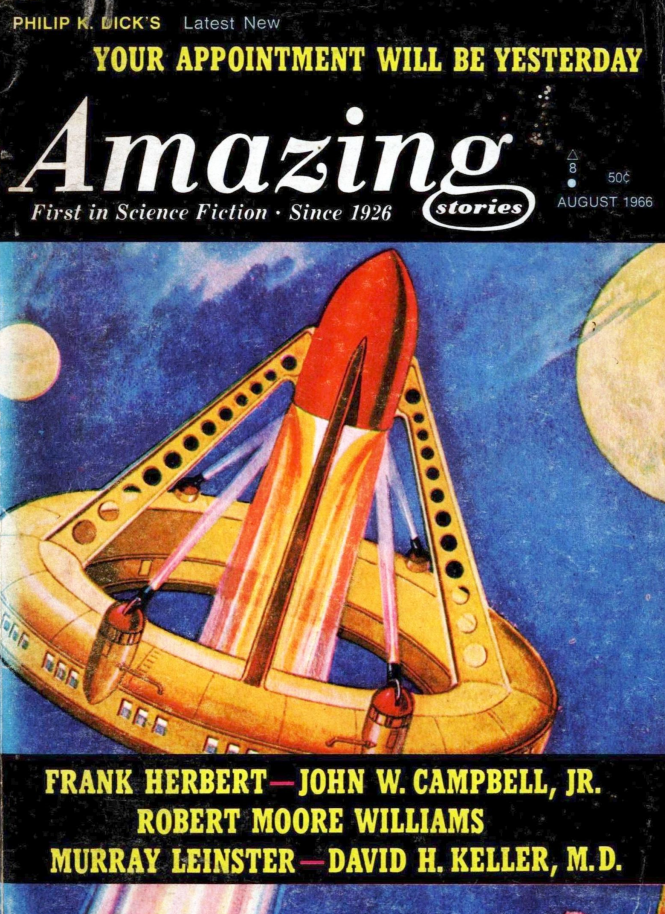

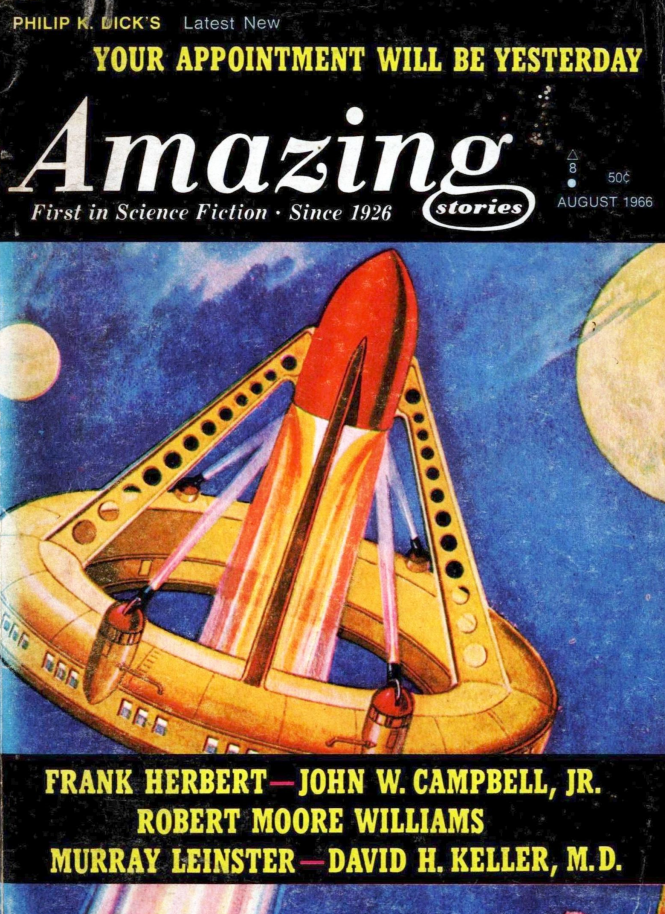

The theme of this August 1966 Amazing is plainly announced on the cover, a crude and silly-looking image by James B. Settles, from the back cover of the July 1942 Amazing, titled Radium Airship of Saturn. You might also think that it doesn’t make much sense, but you’d be wrong! What you see is actually the top two-thirds of the 1942 version; what you’re missing is the surface of Saturn, and a caption: “The motor in this air-ship is a disintegrating rocket-blast caused by the breaking down of a copper core by a stream of powerful radium rays concentrated on it. It acts like a giant fireworks rocket.” It’s science!

by James B. Settles

Inside, the theme is carried forward with the conclusion of the Murray Leinster serial begun in June, a new novelet by Philip K. Dick, and five reprinted stories, particulars below. The brightest spot in the issue is the absence of an editorial, though the usual brief and praiseful letter column is present.

While the editor misses no chance to bad-mouth the magazine’s prior regime, directly and through his selection of letters to publish, one thing has remained constant, and has seemingly intensified: the abominable proofreading. (“Strickly speaking,” indeed.)

There's also a different sort of difficulty facing Amazing and Fantastic now. It's been rumored for a while that they are not paying the authors for the reprinted material, which is now confirmed for those not plugged into the more authoritative gossip channels. Kris Vyas-Myall has helpfully flagged the new issue of the fanzine Riverside Quarterly, in which the editor mentions that he confirmed with Kris Neville that he did not get paid for his recently reprinted story, and confirmed with Damon Knight, president of the newly constituted Science Fiction Writers of America, that this is the general practice.

I suppose this may reflect the publishing practice prevalent in earlier years of buying "all rights" (sometimes simply by so noting on the author's check, with no more formal contract than that). So maybe it's legal, but it stinks. Knight has called on the members of SFWA to boycott the publisher until it changes its ways, and editor Leland Sapiro suggests that readers do the same with the magazines. I'd take that advice, but duty dictates otherwise.

Stopover in Space (Part 2 of 2), by Murray Leinster

Murray Leinster’s latest Western treads a familiar path. There’s a new sheriff, but he’s not really quite in town yet, because somebody doesn’t want him there, and it probably has to do with the stagecoach full of gold that is expected to arrive any day now. It seems like business as usual from the author of Kid Deputy, Outlaw Guns, and Son of the Flying ‘Y’.

Oh, wait. Sorry. Wrong rut. Trying again:

In Murray Leinster’s latest space opera, Lieutenant Scott of the Space Patrol is on his way to take over his first command, Checkpoint Lambda, a station orbiting the star Canis Lambda, whose system is of no special interest except that no fewer than six space lanes cross there. (Didn’t know space has lanes? People established them, I suppose so no one will get lost.) En route, Scott learns that several passengers had been supposed to leave Lambda on a ship recently, but didn’t, under peculiar circumstances—and one of them was “a girl.” This bears repetition, to the author and to Scott; a few pages later, Scott is reviewing the available facts, and notes that “passengers—including a girl—hadn’t left the checkpoint when they should.”

by Gray Morrow

Now, what could be happening? Scott doesn’t know, but he does know the Golconda Ship is expected to show up at Lambda in the near future. That ship is owned by a bunch of guys who went somewhere nobody knows and came back with a load of “treasure” which made them rich, and they go back for more every four years or so. What kind of treasure? Gold, platinum, radioactives, miracle cures from an unknown planet, the secret wisdom of an ancient civilization? Doesn’t say, now or at any other point until the end of the story. For the author’s purposes, you don’t need to know. It’s just a game piece.

So what seems to be going on here? Owlhoots! Er, sorry. Gangsters! Scott is strongly discouraged from debarking onto Checkpoint Lambda, but insists, and finds himself going through the motions of normality with some slovenly types pretending to be the station crew. He meets their nominal mastermind, one Chenery, who pretends to know Scott—and, before too long, he encounters the real power, whom Chenery recruited, and who is known as—Bugsy! He is there to provide and direct the muscle, er, blastermen.*

* No, Bugsy and the Blastermen did not play at last Saturday’s sock hop. That was somebody else.

So, here are the pieces in play: a good guy, some bad guys, treasure to be fought over, “a girl” to be protected. What else do we need? Oh yes, an external menace. How about the Five Comets? The Canis Lambda system has no planets—they all blew up eons ago, and the Checkpoint is attached to one of the bigger pieces—but it has some really fine comets, and they are all going to arrive at about the same time, right athwart the Checkpoint’s orbit—and there’s no astrogator, except for Scott! (One might ask why the powers that be wouldn’t put the Checkpoint in some other location than the entirely predictable convergence point of multiple comets, but one would be wasting time to do so.)

The “girl”—an adult woman, of course—does have a name, Janet, though no others are disclosed. Her full name would have to be (apologies to Alfred Hitchcock) Janet S. MacGuffin (“S” for Secondary), since she drives a part of the plot. One of Scott’s challenges is to keep her safe from . . . well, let her tell it. She says that Chenery “did keep the others from—harming me.” Such an eloquent dash!

But clearly, as in last year’s Killer Ship, women have no role in tough situations other than to create the need for men to protect them. At one point, Scott parks Janet for safekeeping in one of the Checkpoint’s lifeboats, gives her a snap course in operating it if necessary, and reassures her: “It’s not a very good chance. But there aren’t many women who could make it a chance at all. I think you can.” She doesn't have to try. Later, though, Scott gives her something to do—maneuver the station to avoid comet debris while he’s busy elsewhere—and she blows it. But he promises himself not even to hint at criticizing her, and at the end, after all is safely resolved, she is performing women’s other function in Leinster’s fiction as she and Scott get better acquainted.

This one is a little less vapid than Killer Ship, and considerably less irritating, since it lacks the constant reminders that interstellar travel will be just like the eighteenth century. It’s just as verbose as Killer Ship, but the padding is a little better connected to what is actually going on in the story, and there is a bit more cleverness to the plot. So, two stars for this played-out and left-behind author.

Your Appointment Will Be Yesterday, by Philip K. Dick

The other new story is Your Appointment Will Be Yesterday, by the more-prominent-every-day Philip K. Dick, which once more vindicates my warning: when big names show up at the bottom of the market, there’s a reason for it. This is a story about time running backwards. It starts with a guy getting up in the morning (wait a minute—morning?), getting some dirty clothes to put on, and picking up a packet of whiskers to glue evenly onto his face, presumably to be absorbed over the course of the day. So where do these whiskers come from, and who puts them into packets, and how are they distributed? What happens if you run out? And why does anyone bother with them?

by Gray Morrow

It goes on. People begin conversations with “good-bye” and end with “hello,” but they don’t talk backwards in between. Et cetera. Sorry, it doesn’t work. PKD’s specialty is making preposterous ideas at least momentarily plausible, but this one is too long a stretch. It’s not enough for the reader to suspend disbelief; for this story you’d have to shoot it out of a cannon.

There’s more, of course, but not better. Dick does have enough knack as a storyteller to keep things readable as the reader fumes over the contradictions, so, two stars.

The Voice of the Void, by John W. Campbell, Jr.

The Voice of the Void was John W. Campbell, Jr.’s fourth published story, from the Summer 1930 Amazing Stories Quarterly, and at first it’s sort of refreshing: the story of humanity’s quest for survival as the sun is burning out, first disassembling large parts of the solar system and moving pieces closer to the sun, then looking for a new home around a younger or longer-lived star.

by Hans Wessolowski

The story is about 98% character- and dialogue-free, though the astronomer Hal Jus has several cameos along the way. Instead, it chronicles a long course of human discovery and problem-solving, grandiose and grave in equal measure. It is a little reminiscent of Edmond Hamilton’s Intelligence Undying of a few issues back, if that story had been administered a mild sedative.

But things turn dark soon enough. Humanity wants Betelgeuse for its new home. But it turns out there’s no vacancy there—that system is inhabited by energy beings who don’t take kindly to human invasion. Allegedly they are not intelligent, but their facility at fatally repelling unwanted visitors suggests otherwise. Now, Betelgeuse is not necessary to human survival. There’s another star handy; it doesn’t have planets, but the human fleet is so large that humanity could hang out for a few years in orbit and build some suitable planets. But we want Betelgeuse! So the indigenes have to go, and are exterminated in a siege of human-devised energy rays.

Well, that puts a damper on things. Gratuitous genocide can ruin one’s whole reading experience. Two stars with clothespin on nose.

The Gone Dogs, by Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert’s The Gone Dogs (November 1954 issue) is a slightly more interesting bad story than many, rather crudely written—surprisingly so, since it appeared only a year before Herbert’s much more capable and ambitious Under Pressure a/k/a The Dragon in the Sea. On the other hand, it’s free of the turgidity of his current work, especially the characters’ internal monologues about the motives and intentions of one another. Pick your poison.

In the story, an artificially mutated virus is killing off all the world’s dogs, abetted by the fact that humans carry the virus; how to save the species? One solution, highly unauthorized, is to give the last few to the Vegans, who are trying to breed dogs, or something like them. Matters are enlivened along the way by a psychotic dog lover who’s determined to grab one of the last living dogs for herself (and will kill it with the virus she’s carrying). At the end there's a slightly silly and anticlimactic twist.

One thing that’s annoying here is the hyper-facile and acontextual (thoughtless, for short) deployment of standard components from the SF warehouse. At one point the main character needs to dodge a congressional subpoena. What better way than to flee to Vega? All by himself, with a forged pass to a faster-than-light spaceship which any idiot, or at least a biologist, can apparently navigate solo across interstellar distances, without notice and whenever the need arises. There’s no reason in the rest of the story to believe in this capability. This sort of thing was common in ‘50s SF but that doesn’t make it more palatable. Two stars.

The Pent House, by David H. Keller, M.D.

David H. Keller, M.D., is in the position, unusual for him, of providing the least ridiculous story in the issue, chiefly because he essays so little. The Pent House, from the February 1932 Amazing, is a minor exercise in benign crankiness. A rich guy who is also a doctor discovers that humanity is about to be wiped out by the spread of a cancer germ, so he sets up a nice sealed-off apartment on top of a tall building, makes arrangements for a generous supply of life’s necessities and amenities, and advertises for a couple who really like each other to take on a lucrative job for five years. The lucky winners persuade him to stay with them in the (large) apartment.

by Leo Morey

Blissful years pass. The woman of the couple is not feeling well, so the old rich doctor goes in to look at her and some hours later tells the husband, “It’s a girl.” He hadn’t noticed his wife’s pregnancy. Maybe this is not the least ridiculous story here after all.

More time passes, the five years are up, and the old guy goes downstairs to check things out. Turns out the cancer epidemic was thwarted by medical science. So things are the same? No—noisier, dirtier, generally less civilized (to summarize an extensive rant). “It seemed to me that the world has escaped the cancer death so it could die from neurasthenia,” pronounces the doctor. He’s ready to pay the couple the fortune they have earned and bid them adieu, but the wife says forget it, just order up some more supplies and let’s lock the door for another five years of "Heaven in a penthouse." Two stars for competent rendering discounted for triviality.

The Man Who Knew All the Answers, by Donald Bern

The Man Who Knew All the Answers, from the August 1940 Amazing, is bylined Donald Bern, who was actually Al Bernstein, who has half a dozen or so credits in Amazing and Fantastic Adventures in 1940-42, and nothing else in the SF magazines. Frankly, just as well. This is a silly story about a nasty guy named Scuttlebottom, who stumbles (literally) into Ye Village Book Stall, and encounters the proprietor (“He wore a pince-nez. He looked exactly like a person who wears a pince-nez.”), who sells him a book called The Dormant Brain. The book teaches him to become telepathic, so now he knows what everybody thinks of him, which is unpleasant, and he then comes to a contrived bad end as a result of his new talent. One star per the ground rules, despite this story’s utter lack of any reason for existing.

The Metal Martyr, by Robert Moore Williams

Robert Moore Williams’s The Metal Martyr, from the July 1950 Amazing, is a mildly clever but overall pretty silly story about a robot, named Two, who develops the delusion that he is a man—this in the far future, long after a rumored rebellion by robots against humans, and the fall of human civilization. Two flees the robot enclave to avoid having its brain dissolved and replaced, and comes across a couple of humans, named Bill and Ed, never mind the intervening millennia. Two visits them at their home cave, but some of the humans get scared and threaten it, so Two flees deeper into the cave. There it discovers the remains of an ancient mining site full of machinery, skeletons, and books explaining the past and how things got to their present metal-poor state—and showing no robots, revealing that humans once did just fine without them. Two recovers from its delusion of humanity. After giving the humans their past back (although they, unlike robots, can’t read), Two heads back to robotdom and its rendezvous with the acid vat.

by Edmond B. Swiatek

Williams was once a titanically prolific contributor to pulps of all genres, but most frequently SF and fantasy, and within them, most frequently to Ray Palmer’s Amazing and Fantastic Adventures, where he was part of the regular crew that filled those magazines with juvenilia. Palmer was gone before this one appeared, but it is true to the tradition. Two stars, charitably.

Summing Up

There’s not much to say. The last issue finally achieved consistent readability, a first for the Sol Cohen regime. Now, back into the murk and muck.

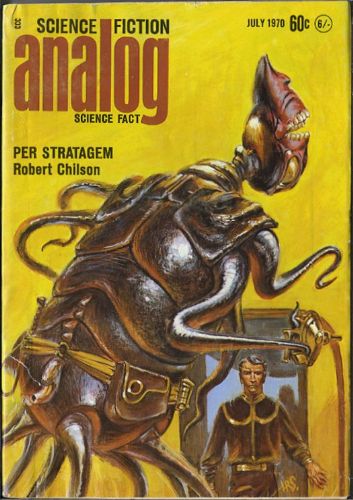

![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

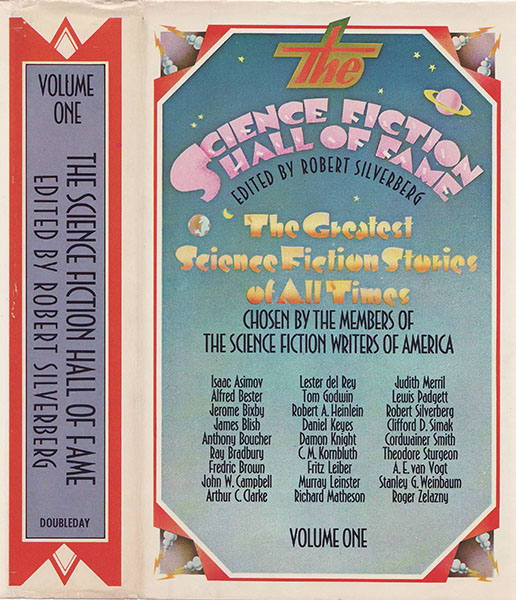

![[May 6, 1970] Wondrous and Astounding (<em>The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One</em>, Part One)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/SCNCMVLM161970-516x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1966] Ridiculous! (August 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/amz-0866-cover-665x372.png)