by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

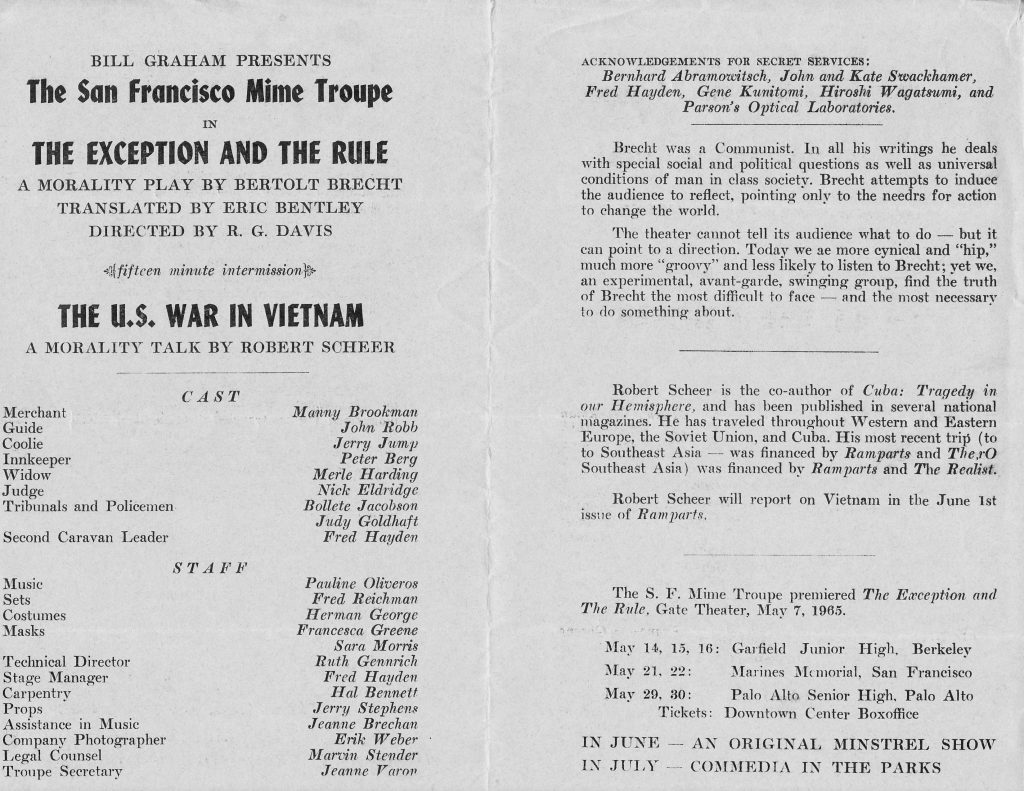

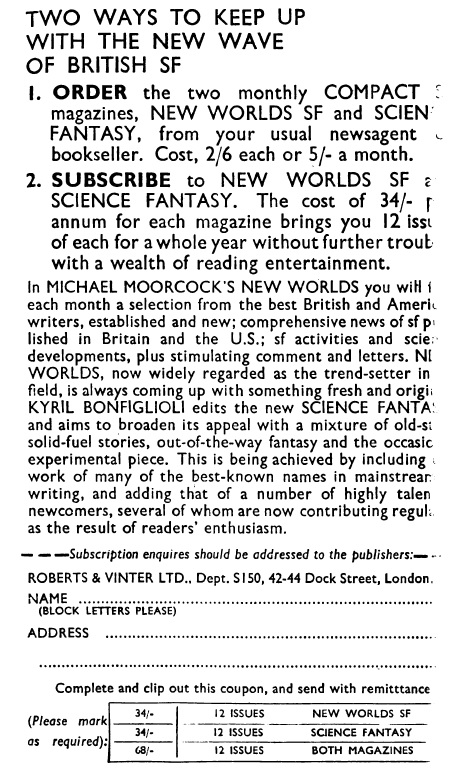

After the hoo-ha of celebrating New Worlds’s 150th issue last month, we’re back to some sort of normality. But if you thought things were getting boring – think again! We are all counting down to the much-expected Worldcon in the Summer, only a couple of months away from the time I’m writing. This includes the magazines themselves.

But first, let’s get to the issue that arrived first in the post this month: the June issue of Science Fantasy.

We have another painting on the cover by the prolific Keith Roberts. I almost like this one, although your guess as to what it shows is as good as anyone else’s.

Interestingly, a glance at the front and back covers shows us (once again) names mentioned that are not in this issue. This includes the aforementioned Keith Roberts, with stories clearly held over for some reason. And whither, Philip Wordley?

On a more positive note, I do like Kyril’s Editorials, perhaps more than Mike Moorcock’s in New Worlds. Mike’s prose always comes across as a lecture, whilst Kyril’s is more chatty. This may be relevant this month, as Kyril uses an Aldiss quote at a starting point,"The job of a critic consists of knowing when he is being bored, and why", and then takes to task the term ‘well-written’, a phrase I have been guilty of using often in these here articles. He makes the point that well-written can mean that the prose is florid – “it exhibits bursts of purple mandarin-fiction” or is ‘easy to read’ and therefore less boring.

And using that analogy I might be as bold as to say that Moorcock’s New Worlds editorials are erudite, whilst Kyril’s are less boring. His use of a James Bond book to explain this is inspired, although the topic is left with a promise to come back to it at a later date.

To the stories themselves.

The Impossible Smile (part 2 of 2), by Jael Cracken

The second part of this serial by Brian Aldiss under a different name is not the only time we will come across Brian this month. The Impossible Smile begins where we pretty much left off – in a future dystopian state telepath Conrad Wyvern has been captured and taken to the Moon where the artificial intelligence ‘Big Bert’ is waiting. The government through their lunar representative Colonel H hope to link Wyvern to Bert the Brain and so read the minds of the whole population. For Wyvern, the risk is that the process will kill him, as it it did previous test subjects.

So: a fast-paced tale with lots of action and running about. Much of this second part is about what happens when Wyvern & Big Bert are connected, and Wyvern’s subsequent escape from the hospital he is imprisoned in. (I know – he’s on the Moon! Where would he escape to?) There’s some typical inner mind psychedelia and out of body experiences (walls of eyeballs!) which seem rather de rigueur at the moment. All hail the telepathic New Order!

Aldiss continues to tell an entertaining yarn which is great fun, if ultimately rather superficial. Not his best, but still readable. 3 out of 5.

Great and Small, by G. L. Lack

Not a name I immediately know, although he/she was in the New Writings in SF 2 story collection that I couldn’t finish. This is his/her first time in Science Fantasy. Great and Small is a strange little story about a man and his ongoing conversation with a fly, that often seen but generally unnoticeable insect. The man wakes up in a hospital to find a fly buzzing around – but wait! All flies are extinct, thanks to yet another apocalyptic event. The man feeds the fly some jam and then it buzzes off to meet another fly, presumably to dominate the new global ecosystem. As I said, odd and although it is interesting, not really worth much attention. 2 out of 5.

Ploop, by Ron Pritchett

Names are important, aren’t they? I must admit that the childish part of my brain struggled to cope with a character named ‘Ploop’.

Ploop is an alien and this minor story is about its first meeting with another alien race. Unsurprisingly, the aliens are humans and although Ploop looks like a dog it is in fact something else much more dangerous.

Ron is a new author and whilst this is a valiant effort, it shows. I suspect we may not see much more of him. A placeholder using a tired idea. 2 out of 5.

Peace on Earth, by Paul Jents

Paul was last seen with the very odd Unto All Generations in the July/August 1964 issue. This is one of those stories with a twist in the tail, the story of the Earth’s first landing on the Moon with a horrible discovery at the end. Suffice it to say that the Moon is not made of green cheese but has something much worse. Another tired old cliché. 2 out of 5.

Deterrent, by Alastair Bevan

The return of someone who has become a recent regular, that of Keith Roberts by another name. Unsurprisingly, the topline describes Mr Bevan as “one of our best finds”. Deterrent is a story of seemingly primitive cave-people living a tribal existence until they discover what appears to be a nuclear weapon, the unsurprising post-apocalyptic twist in the tale. Not really anything to shout about, as something that has been done before and often. Must admit, though, that it is the first time I’ve ever read of Gods having a “xylophone presence.” 3 out of 5.

A Pleasure Shared, by Brian W. Aldiss

A name that needs no explanation from me – have I reminded you this month yet that he is to be a Guest of Honour at the London Worldcon in August? His prolific nature is noticeable at the moment. Last month he had published two very different stories in the two magazines – this month he has two in the same issue. A Pleasure Shared is however a reprint, first published in the USA in December 1962. The banner heading is very careful to point out that it is not science fiction in the accepted sense of the word, but “a triumph of empathetic fiction” – whatever that means.

What A Pleasure Shared actually is is a contemporary horror story, written from the perspective of a killer. Outwardly Mr Cream seems nice, polite and pleasant, but as we read his internalised monologue here it is clear that he is really not well. He has murdered, more than once. We know this from the beginning, because the woman he killed last night is still in his bedsit room. This would be bad enough but an accident to his widowed neighbour means that things take an unexpected turn at the end. This is really one in the style and tone of William Powell’s film Peeping Tom from a couple of years ago or Robert Bloch’s Psycho. It is shocking and memorable. Is it science fiction? No. But it is a very, very good story. I can see why Kyril has wanted to publish it. The best of the issue for me, and certainly the most memorable. Who would have thought that that nice Mr. Aldiss could come up with something so depraved? Shame its taken so long to appear here in Britain, though. 4 out of 5.

Prisoner, by Patricia Hocknell

Back to something a little more mundane, now. Another story from Patricia, last seen in the January/February 1965 issue with Only the Best. It begins as if the narrator is a convict with no knowledge of where they are or how they got there. All is revealed at the end with another twist in the tale. Again, OK, but nothing really new. 3 out of 5.

In Reason’s Ear, by Pippin Graham

Another new name to me. In this story, John Wetherall is a man recently returned to London after working in West Africa for the UKESCM (the United Kingdom Educational, Scientific and Cultural Mission) who seem to be a branch of the Foreign Office. John finds himself in trouble when after helping an old friend he discovers that the friend is supposedly dead, killed on an expedition to the Moon a few months ago.

I quite liked this one, although it is remarkably mannered. The US Intelligence Service at one point knock on a door to be told “Go away, I don’t answer my door at night”, which they do! This is in marked contrast to some other elements of the story which show a world out of control. Wetherall is shocked to find that London is prone to rampaging teenagers with little police support available to tackle them, and Graham does well to describe what he sees as he goes about the city. There are regular gatherings of these dancing, marijuana-smoking, knife-wielding, riotous young tearaways and they seem to put the rest of the general public in a state of fear – as if the general story of the Moon being dangerous wasn’t enough.

Whilst I see the story as a prime example of paranoiac adults being fearful for their future, I liked some of the ideas shown here. The story fizzles out with a now-traditional enigmatic ending, but overall it kept me reading. Whilst not superlative, and some definite flaws, it is one of this month’s better offerings for me. 3 out of 5.

Xenophilia, by Thom Keyes

A name we’ve come across before, in New Worlds in January 1965. His last story (Election Campaign) was underwhelming. Xenophilia is a story of alien love that begins like Casino Royale in Space before delving into the realms of alien sex. Short, it reads like a more explicit version of the old Bug-Eyed-Monster stories of yesteryear. I suspect that it is meant to shock. However, whilst it is still weird, I found the short story more palatable than his last. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

Let’s start with a good point. Despite Brian Aldiss appearing twice, there is a greater range of stories this month, and I’m pleased to see that there are both more new writers and even a woman writer in this issue. This can only be good for the field, but only if the material published is good enough to stand merit – in other words, (with apologies to Kyril and Brian Aldiss, paraphrasing the Editorial) it is well-written. And that’s my problem with this issue.

It is clear that there’s been some last-minute changes made to what is included here, and although there’s nothing really bad in this issue, much of it isn’t that good either. The Pippin Graham story was odd yet memorable, whilst the standout by far was the second Aldiss story. Normally this would be a cause for celebration, but it is a reprint. This is not the first time in Science Fantasy or New Worlds in recent months where the best material is old material – a worrying trend. Overall, an oddly underwhelming issue. Not bad but not great.

Let’s go to my second magazine.

The Second Issue At Hand

After last month’s focus on stories, we’re back to normal with Issue 151. There’s book reviews, science articles, letters – and some fiction.

The cover shows a change though. The un-credited image shows that we have (finally!) moved away from the circle covers to something less circular and more abstract. It is certainly colourful and grabs your attention, but is it science fiction?

The Editorial also raises the ongoing discussion of what is Science Fiction, a debate that has been going on for months, if not years. Moorcock tries to examine this further but spends much of his time eliminating what Science Fiction is not. The title, ‘Process of Elimination’ explains why. And its findings in the end? Not a lot, other than the definition should be broad rather than narrow. It then looks at how the American magazines have evolved to illustrate this, citing The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction as the best example of how to move on from Campbell’s rather restrictive definition in magazines like Analog. This seems to be a determined attempt to broaden the template of New Worlds, something which Moorcock has been determined to do since he took over as Editor.

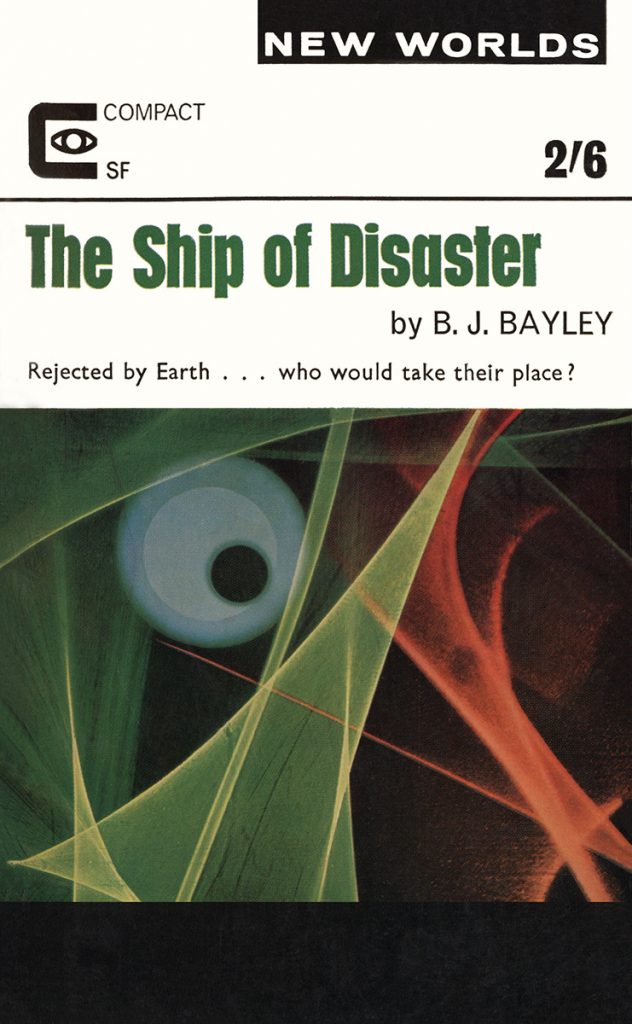

The Ship of Disaster, by B. J. Bayley

Elen-Gereth – the elf who wants to be Elric. Art by James Cawthorn.

When this one begins it feels like Bayley has been reading a lot of Moorcock’s Elric stories – the vessel named The Ship of Disaster is a ship captained by Elen-Gereth, an elf, who takes great delight in sinking a human trading vessel and taking hostage its captain, a human named Kelgynn. All of this wouldn’t be amiss in the seas around Elric’s Melnibone, though this lacks the panache of Moorcock’s version. Elen-Gereth is appropriately brooding and complex. However, a story that reads like it should be in Science Fantasy rather than New Worlds has the twist that makes it more science-fictional, although its connection to SF is relatively slight. 3 out of 5.

Apartness, by Vernor Vinge

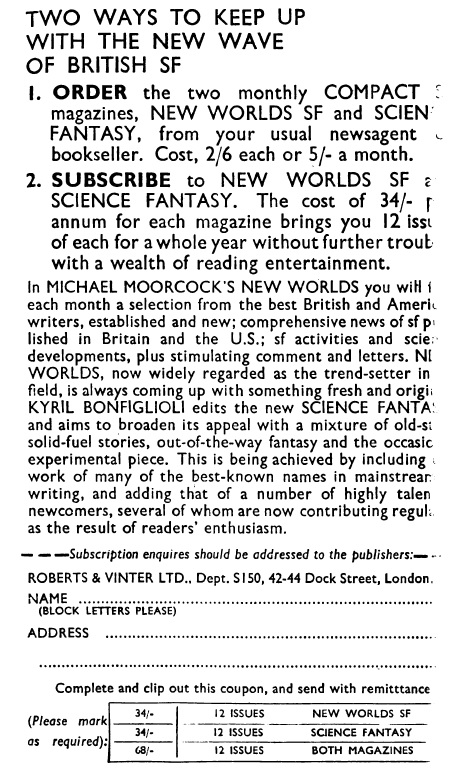

This is the first story I’ve read from a relatively new American writer. Apartness is a post-apocalyptic tale, with the Earth’s Northern hemisphere destroyed two hundred years ago in the North World War. The regions of the South exist as disparate groups by using a strange combination of science and mysticism – astrologers make decisions based on scientific evidence, for example.

The story is essentially a conflict between two groups in the Antarctic. One of them is a group from the Southern countries and the other a new tribe found on a general observational recce. The twist in the story is that the new group is the offspring of two refugee ships, luxury cruise liners fleeing the conflict. There is talk about what to do with them – should they continue to be observed but undisturbed, or should they be decimated as the descendants of white oppressors?

I enjoyed it a lot and expect to read more of his writing in the future, although it does feel more like something for Analog and The Magazine of Fantasy and SF than New Worlds. But a promising start – I suspect we’ll see more from this talented new writer in the future. 3 out of 5.

Convolutions, by George Collyn

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.

George Collyn returns with a story that is quite different to his last, which was In One Sad Day in the April 1965 issue. It is a story of the awakening of an alien that feeds on fear and finds Earth an suitable place for colonisation. One of those very common stories that begins with “Who am I?” and then “Where am I?” (See also Patricia Hocknell’s Prisoner in Science Fantasy this month.) 3 out of 5.

Last Man Home, by R. W. Mackelworth

R W Mackelworth has a tendency of writing strange tales with varying degrees of success. His last was the attempt to be humorous story, The Changing Shape of Charlie Snuff in the April 1965 issue. It didn’t work for me, but this story is less funny and more to my tastes. Even if it is yet another post-apocalyptic story. Here we have bowler-hatted Jennings, a wandering tinker who relates his experiences to us by describing what he has seen and who he has met on his travels in the post-nuclear wilderness. On his arrival in the city-state of Gat we find Jennings and his donkey companion Jess arrive to tell the city elders that there is life in the Wastelands and then returns there. There are positive signs of life, leaving a certain degree of optimism in the end. The emphasis is on what is around Jennings rather than Jennings himself. It’s fine, if too long, but I’ve read it all before – notable for its un-remarkableness. 3 out of 5.

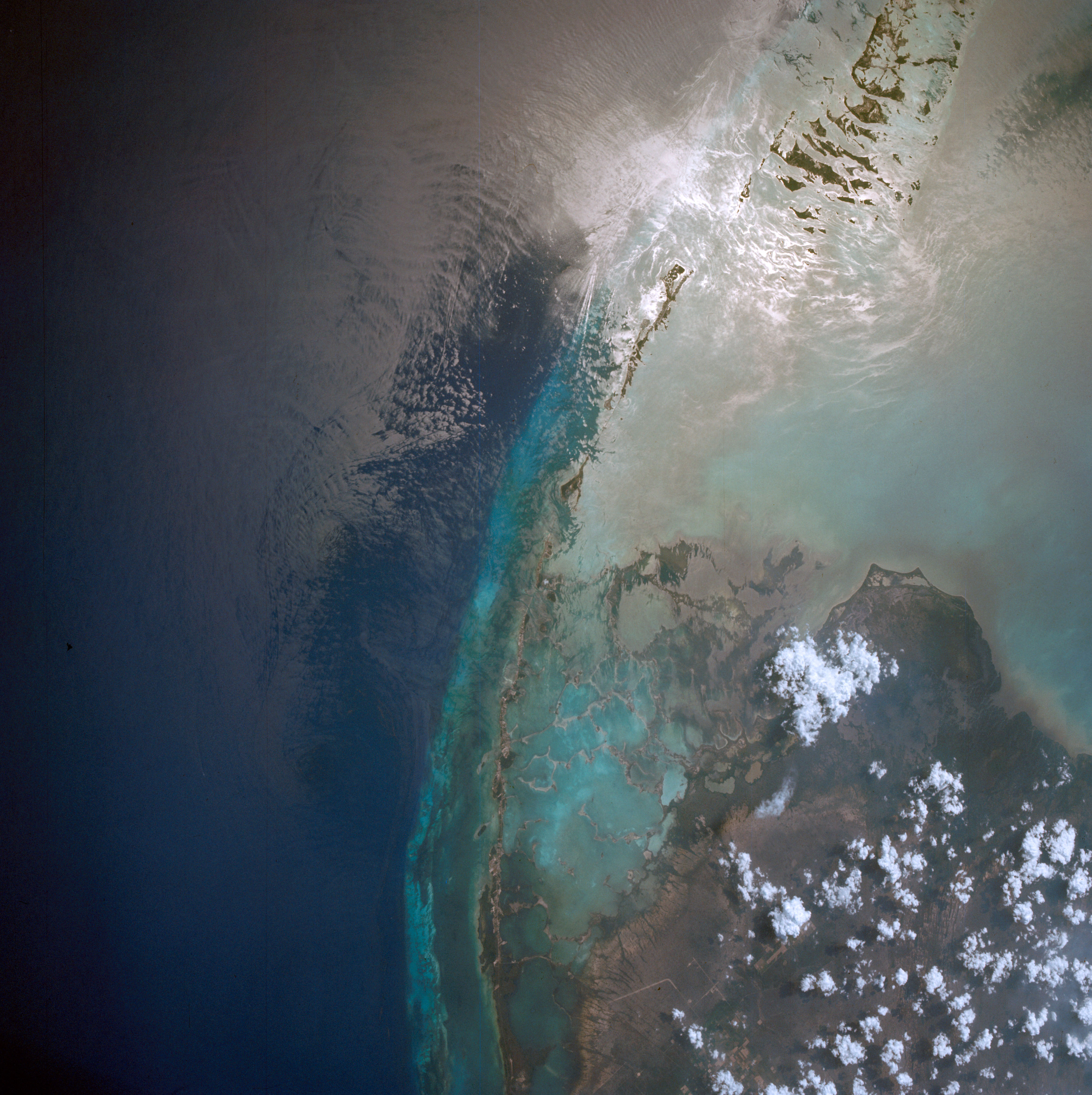

The Life Buyer (Part 3 of 3), by E.C. Tubb

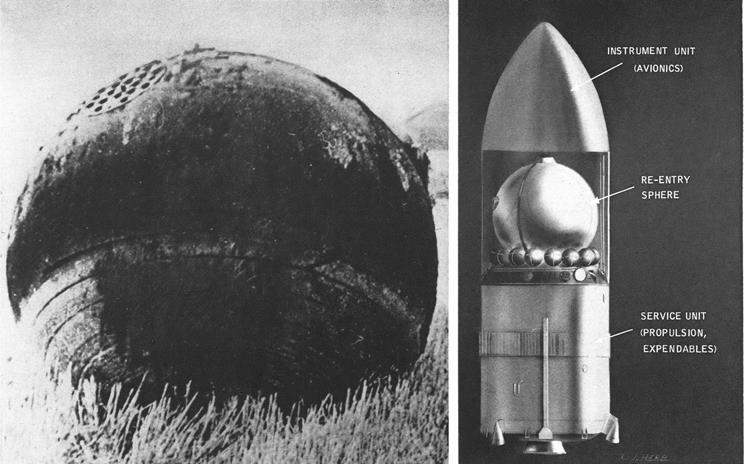

The Sand Pit of Terror! (Actually, Moondust – but you get the idea). Art by aTom.

We begin the last part of this entertaining three-part serial by following Ransom, the suspect our two detectives Dale Markham and Steve Delmonte have been monitoring. Ransom is looking for Joe Langdy, a search that will take him to the Moon. The first few chapters of this part we spend following Ransom in his search, which is pretty pointless. The end of this revenge story is where the two detectives explain their solution as to who wants to kill millionaire Marcus King. It wraps everything up pretty quickly in the end. It’s a solid enough tale, with the moral that money can’t quite buy you everything. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews, Articles and Letters

I’m really pleased to see the return of Book Reviews, Science Articles and Letters this month. I missed them last issue.

The Book Reviews seem to want to make up for their absence of last month by taking up what seems like more space than usual this time around. Assistant Editor Langdon Jones deals with the longer, more-in-depth reviews this month of A Man of Double Deed by Leonard Daventry, which is readable, and Sundog by B N Ball, which wasn’t. John Brunner’s Telepathist was surprisingly new and interesting, and seen by Langdon Jones as one of Brunner’s best, before ending with the cryptic comment that it “….will probably be the last really good novel of science fiction that we will see from British writers.”

There are minor reviews for Ray Bradbury’s ‘tremendous’ Something Wicked This Way Comes and Of Demons and Darkness by John Collier, which is ‘repetitive’. John Carnell’s story collection New Writings in SF 2 is given a one-sentence review of “not very interesting”. (And having tried to read it myself, I can only agree.)

Charles Platt gives us one in-depth review this month, under the title of Diary of a Schizoid Hypochondriac. He reviews Brian Aldiss’s Earthworks, which he describes as “a monotonous diary of a schizoid hypochondriac of dubious intelligence who is pushed around throughout the book, including an irrelevant three-chapter flashback, by Higher Powers, until finally discovering an Answer which was obvious to the reader two chapters previously.” Hmm – not a fan then, Mr. Platt?

Editor Mike Moorcock as James Colvin offers us seven ’Quick Reviews’ of After Doomsday and Shield by Poul Anderson, The Martian Way by Isaac Asimov, The Drowned World by J G Ballard, New Writings in SF 3 and Lambda 1 and Others both edited by John Carnell and The Seventh Galaxy Reader edited by Frederik Pohl.

As you might expect from Colvin/Moorcock, he is effusive about the Ballard and the Carnell collections, and more scathing of the American imports. He defends his opinion of Poul Anderson’s work (like Mr Platt earlier, he’s not a fan either), preferring Asimov’s The Martian Way because Asimov is better on the science and more tightly controlled in his writing.

He also makes the claim that although he thought The Magazine of Fantasy and SF was his favourite American magazine, reading The Seventh Galaxy Reader has made him change his mind. (Pause here whilst our reviewer of Galaxy here at Galactic Journey picks himself off the floor…)

One oddity: We have James Colvin, who remember is really Mike Moorcock, reviewing Warriors of Mars by Edward P Bradbury, who is really Mike Moorcock. Confused? An Edgar Rice Burroughs influenced story, it is unsurprisingly “as good as anything by the Old Master”. Hmm.

The article is Gas Lenses Developed for Communications by Laser, a title which describes the article admirably.

The Letters pages continue to debate the ongoing issue of what is science fiction, and therefore what should or shouldn’t be included in New Worlds.

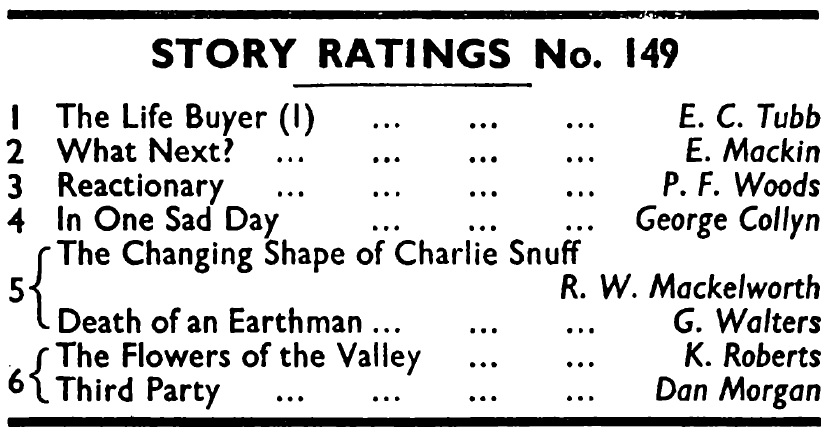

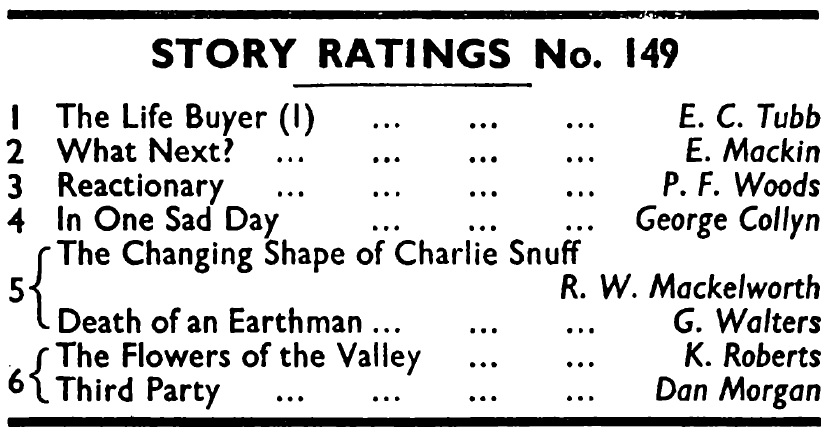

Ratings this month for issue 149 (the April 1965 issue). Life Buyer (part 1) doing well. Lots of joint runners up, which suggests to me either few reader responses or an issue that divides readers.

Summing up New Worlds

This is a good solid issue, though rarely outstanding. I enjoyed it more than the ‘Star Issue’ last month, if I’m honest. The title story I’m not sure that I totally got, but the Tubb serial was nicely done, if a little drawn out. Vernor Vinge is a name to watch out for in the future, I think.

Summing up overall

Both issues this month are solid, yet rather mundane. Science Fantasy seems to have gone for more stories and a greater variety, New Worlds has fewer stories but is mostly based on work by more New Worlds regulars. Like last month, the most memorable story (Aldiss’s A Pleasure Shared) is in Science Fantasy, but New Worlds is better overall. It is a lot closer than last month, but in the end this month’s best issue for me is Science Fantasy.

And that’s it for this time. Until the next…

![[June 8, 1965] A Walk in the Sun (the flight of Gemini 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650608Gemini_Four_patch-471x372.jpg)

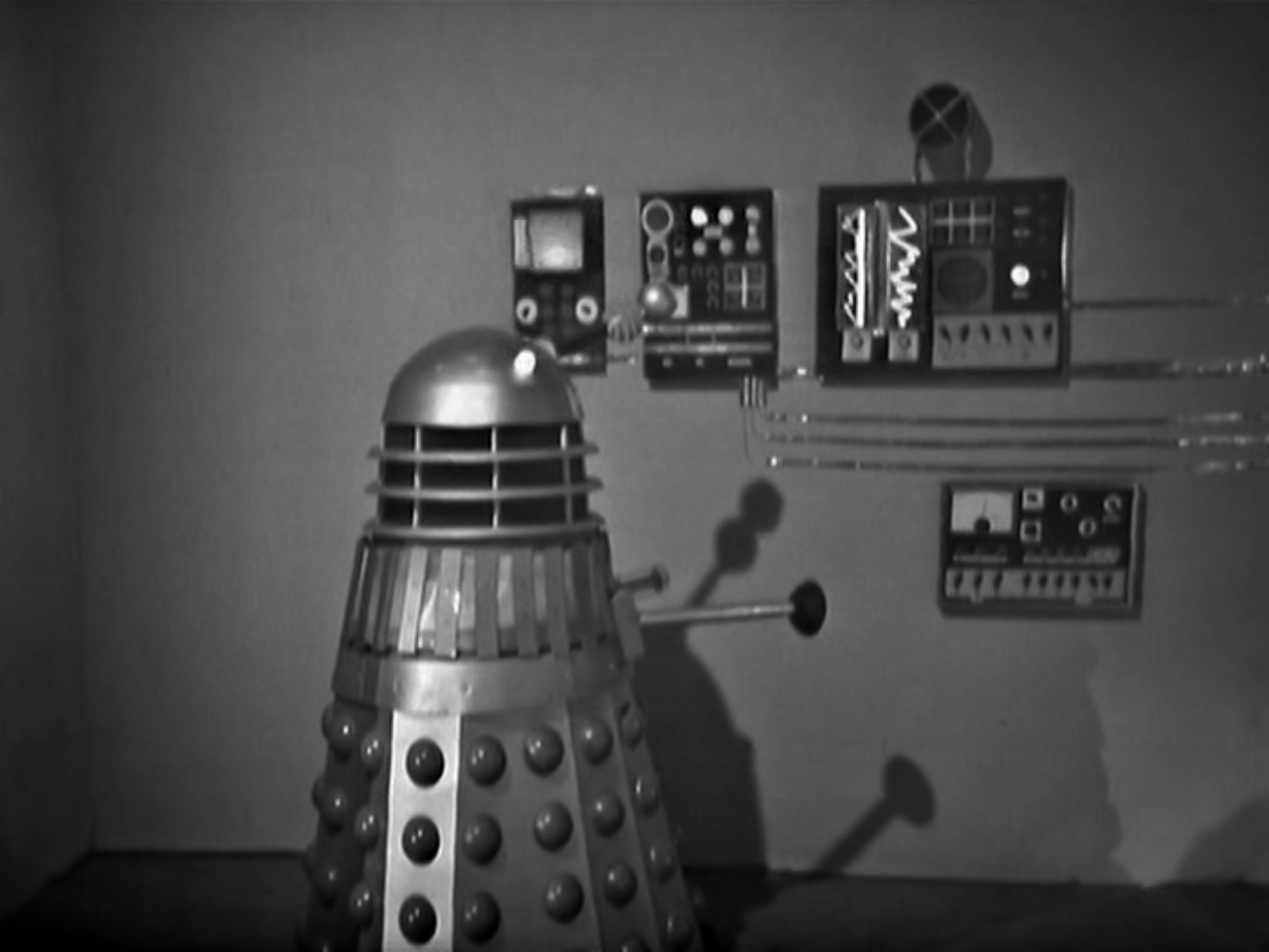

![[June 6, 1965] The Dawdle, More Like (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Chase [Parts 1-3])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/060665daleksinthedunes-672x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1965] Below the Ramparts](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650604mag-672x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1965] Heck in a Handbasket (July 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/1965-07-IF-cover-653x372.jpg)

![[May 30, 1965] Ticket to Ride (May space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650530pegasus2-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1965] Heavyweight's Burden (June 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650528cover-663x372.jpg)

![[May 26th 1965] Mind Control, Aldiss and Time Travel (<i>New Worlds and Science Fantasy, June 1965</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650526coversnew-672x372.jpg)

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.

Appropriately dark art for a dark story. Art by Douthwaite.

![[May 24, 1965] Two faded stars (May Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650524cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1965] Goodbye and Hello (June 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fantastic_v14n06_1965-06_0000-2-672x265.jpg)

![[May 20th, 1965] Monokini: The Madness Continues!](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/https___blogs-images.forbes.com_tomteicholz_files_2019_05_Claxton_Topless-bathing-suit-by-Gernreich-1200x1217-2-672x372.jpg)