by Gideon Marcus

Time of (no) change

Seasons don't mean a whole lot in San Diego. As I like to say, here we have Spring, Summer, Backwards Spring, and Rain. All of these are pretty mild, and folks from parts beyond often grumble over the lack of seasonality here.

I grew up in the Imperal Valley where we had a full four seasons: Hot, Stink, Bug, and Wind. San Diego is a step up.

Judith Merril, who writes the books column for F&SF these days asserts that there is a seasonality to science fiction as well, with December and January being the peak time of year in terms of story quality. If it be the case that the solstice marks the SF's annual zenith, then one might expect the equinoxes to exhibit a mixed bag.

And so that is the case with the latest issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which contains stories both sublime and mediocre. Trip with me through the flowers?

Spring is here

by Jack Gaughan

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, by Philip K. Dick

Given the prolificity with which Dick produces SF these days, one can hardly believe there was a long time when he'd taken a hiatus from the genre. This latest story fuses his recent penchant for mind-expanding weirdness with the more straight science fiction characteristic of his work in the 50s.

To wit, Douglas Quail is a humdrum prole who dreams big. Specifically, he really wants to go to Mars, but such privilege is reserved to astronauts and high grade politicians. Luckily, there is an organization whose business is literally making dreams come true…or perhaps I should say Rekal Incorporated makes true come dreams. They inject their clients with artificial memories, lard them with convincing physical ephemera, and so a dream becomes reality — at least for the customer.

But when Quail is put under for the procedure, it turns out that he already has memories of a trip to Mars, which have been imperfectly wiped. In short order, Quail becomes the center of a spy thriller, pursued by countless government agents.

On the surface, this is a fun gimmick story, but knowing Dick, I'm pretty sure there's a deeper thread running through the plot. Indeed, clues are laid that make the reader wonder if the entire story is not the phantom adventure, deepening turns and all. As with many recent Dick stories, the question one is left with is "What is reality?"

Four stars.

by Gahan Wilson

Appoggiatura, by A. M. Marple

A flea with an amazing tenor and the music-loving but otherwise talentless cat on which he resides, get swept into the world of urban opera. Can their friendship withstand sudden fame?

This silly story by newcomer Anne Marple shouldn't be any good, but the whimsy of it all and the utter lack of explanatory justification keeps you going for a vignette's length.

Three stars.

But Soft, What Light …, by Carol Emshwiller

Spring is the time for romance, and so a fitting season for this piece, a love story between a computer with the soul of a poet, and the young woman who wins its heart.

Lyrically told, avante garde in the extreme, and just a bit naughtier than the usual, But Soft makes me even more delighted to see Carol Emshwiller return to the pages of this magazine.

Five stars.

The Sudden Silence, by J. T. McIntosh

The city of New Bergen on the planet of Severna goes silent, and a rescue team is dispatched from a nearby world to find out what could suddenly quiet the voices of half a million souls.

This novelette would be a lot more tolerable if 1) the culprit were more plausible and 2) McIntosh didn't have two of the male members of the team more interested in seducing their crewmates than saving lives.

It's a pity. McIntosh used to be one of my more favored authors. These days, his stuff is both disappointing and difficult to read for its shabby treatment of women (though at least he includes them in his futures, which is uncommon).

Two stars.

Injected Memory, by Theodore L. Thomas

The latest mini-article from Mr. Thomas is about the promise of skills and experiences induced with genetic infusions. It's a neat idea, lacking the usual stupid execution the author includes at the end of these. I don't know if the article's inclusion in this issue alongside the Philip K. Dick story mentioned above was serendipitous or deliberate, but I suspect the latter.

Three stars.

The Octopus, by Doris Pitkin Buck

Time is an octopus, tearing us in both directions.

Decent poem. Three stars.

The Face Is Familiar, by Gilbert Thomas

I had to look this story up twice to remember it, which should tell you something. A Lovecraftian tale of terror recounted by one man to another in Saigon. The latter has seen real horror. The former saw his wife preserved after death in an…unorthodox manner…which just isn't as shocking or interesting as is it's supposed to be.

Some nice if overwrought storytelling, but not much of a story. Two stars.

The Space Twins, by James Pulley

There was a hypothesis going around for a while that long term exposure to weightlessness would have not just adverse physical but psychological impacts. In this piece, two astronauts on their way around Mars revert to their time in the womb and have trouble returning.

Clearly written before Gemini 6, it comes off as both quaint and facile.

Two stars.

The Sorcerer Pharesm, by Jack Vance

Continuing the adventures of Cugel the Clever in his quest to bring back a magic item to the wizard Iucounu, this latest chapter sees the luckless thief happen across an enormous carved edifice. Its goal is to entice the TOTALITY of space-time into the presence of the great sorcerer, Pharesm.

Of course, nothing goes as planned for Pharesm or Cugel. Clever byplay, some good fortune, lots of bad fortune, and a bit of time travel ensue.

Vance strings nonsense words and scenes together with enviable talent, but the shtick is honestly running a bit thin.

Three stars.

The Nobelmen of Science, by Isaac Asimov

Instead of a science article, the Good Doctor offers up a comprehensive list of Nobel Prize winners by nationality. Seems a bit of a copout, though I imagine it'll be useful to someone.

Three stars.

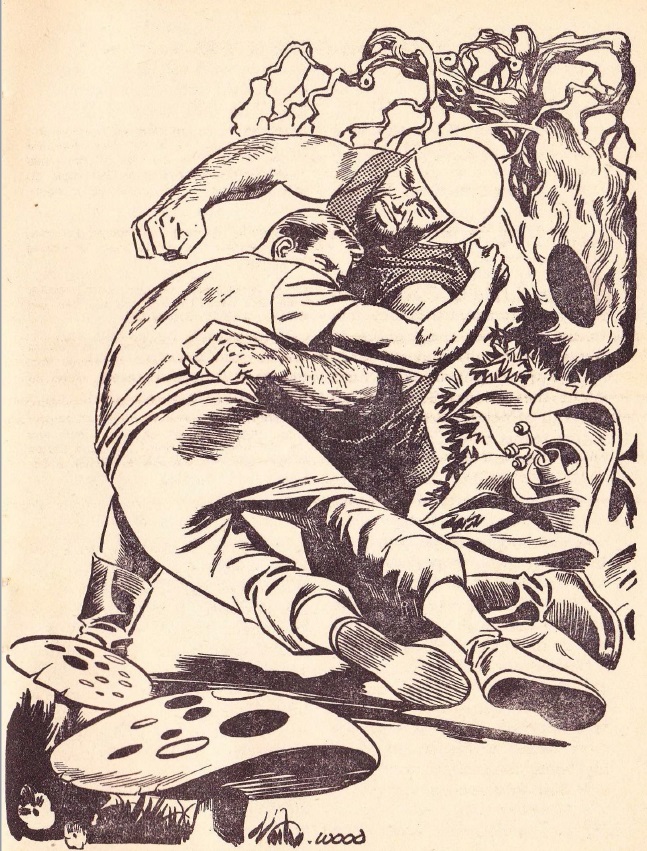

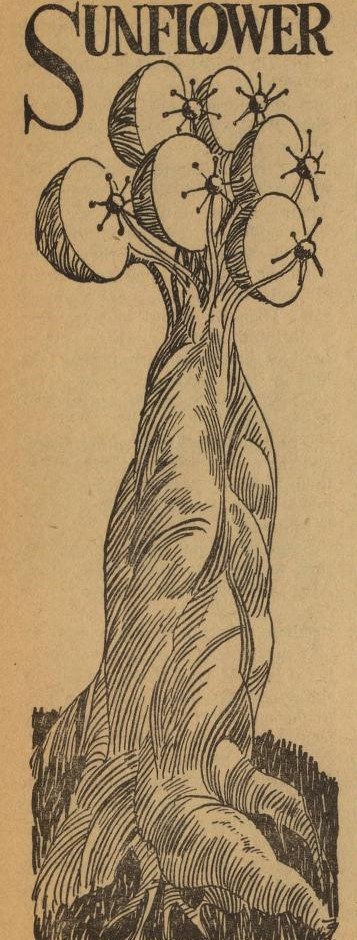

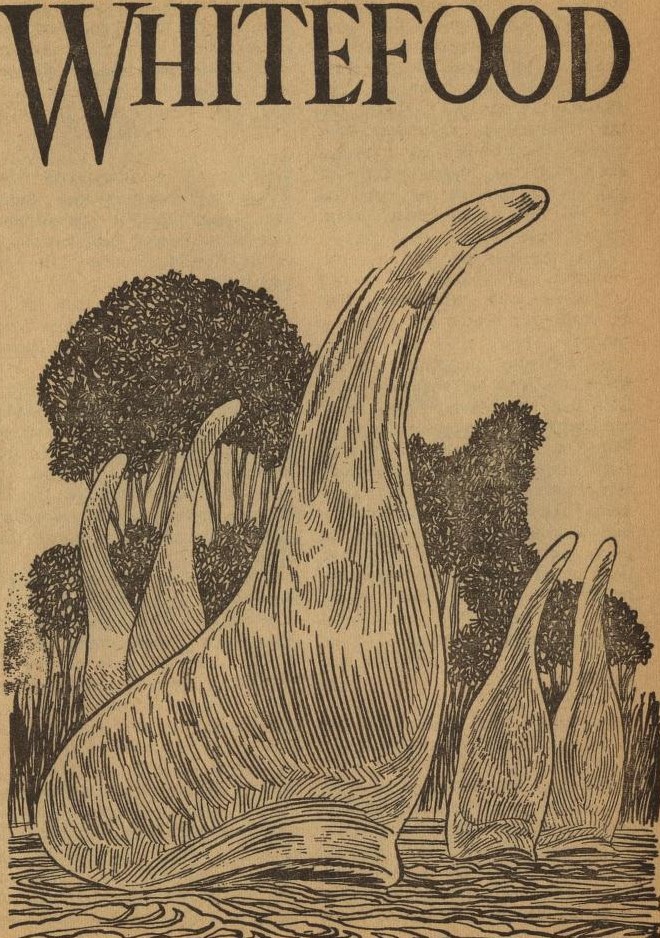

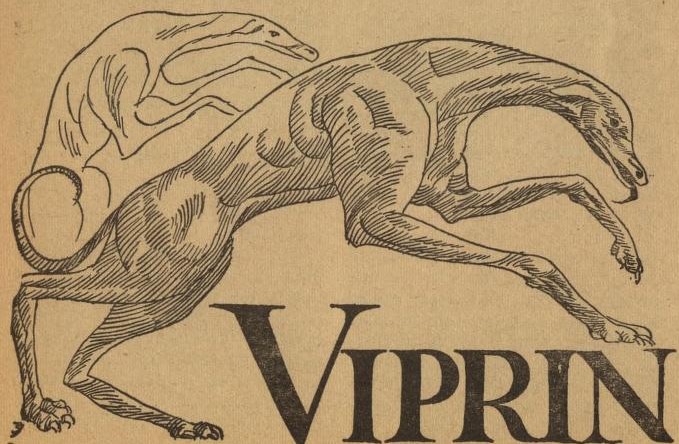

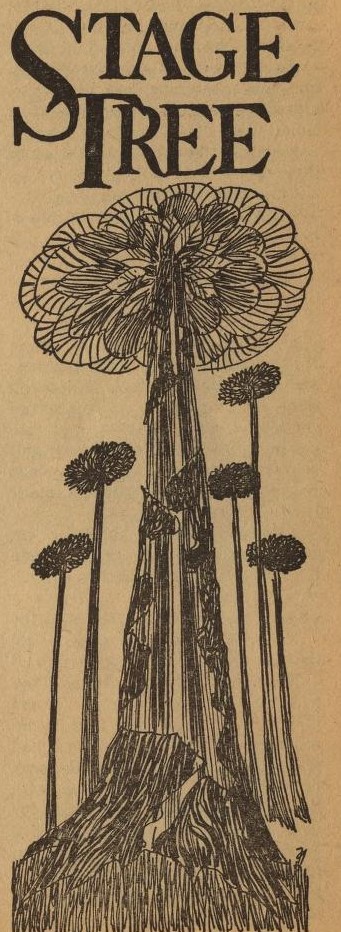

Bordered in Black, by Larry Niven

Lastly, Niven returns with an effective story of two astronauts who head to Sirius and encounter a clearly artificially seeded world. Is it merely an algae farm planet, or is there something more sinister going on, associated with one of the continents, fringed with an ominous black ring?

Niven is great at building a compelling world, and the revelation at the end is pretty good. It's a bit overwrought, though. Also, I'm not sure why Niven would think Sirius A and B are both white giants when Sirius B is famously a dwarf star.

Anyway, four stars, and a good way to end an otherwise unimpressive section of the magazine.

Spring comes finally

And with the equinox, I turn the last page of the issue. In the end, the April F&SF is a touch more good than bad, which is appropriate given the now-longer days. Will the magazine obey the seasonal cycle and turn out its best issue in June (at odds with Ms. Merril's predictions)?

Only time will tell!

Spring is also the time for new beginnings — a fitting season to release its new daughter magazine, P.S.!

![[March 22, 1966] Summer in the sun, winter in the shade (April 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660320cover-672x372.jpg)

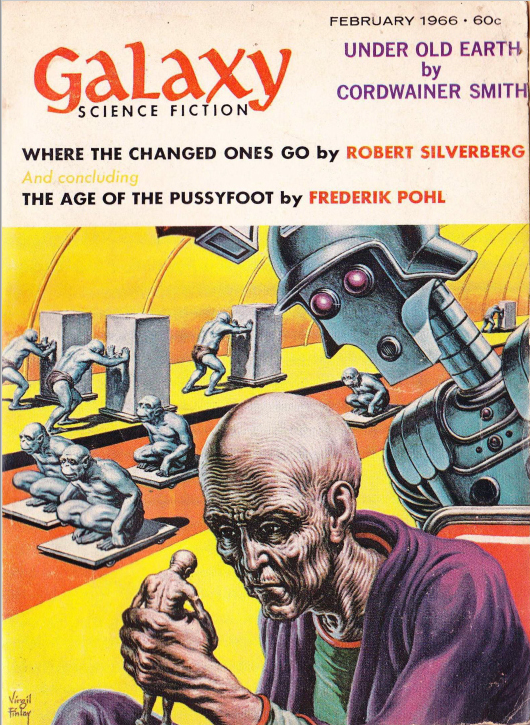

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

![[June 18, 1965] Galactic Doppleganger (July 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650618cover-578x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1965] The Big Picture (March 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v02n06_1965-03_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[November 7, 1964] Landslides and Damp Squibs (December 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641107cover-672x372.jpg)