by Gideon Marcus

It's a dirty business

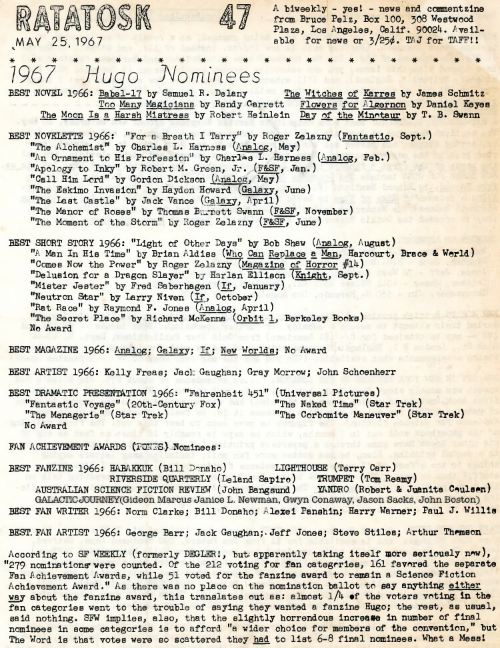

Ever since Harlan Ellison started flapping his gums about how dangerous his new anthology Dangerous Visions is, it seems a seal has been broken.

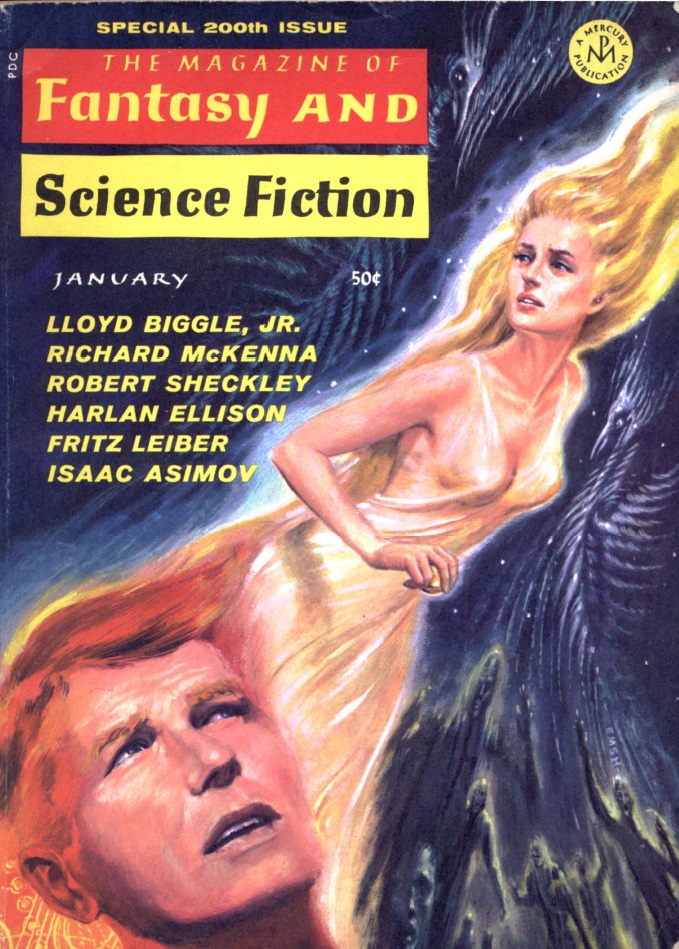

First, Michael Moorcock started putting nudes on the covers of his newly taken-over New Worlds. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction started using the word "shit" liberally. And this month, every other story features sex in varying degrees of luridity.

I'm not complaining, mind you. These things have existed in books and in avante-garde publications like Playboy for years. But it's always a bit startling to find the words you hear commonly on the street suddenly appearing in previously staid venues. Sort of like how Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf shocked everyone. As fellow traveller John Boston noted, with books and girlie mags, one knows what one is getting into. But with media that enjoys wider distribution, which could be viewed or read by the the little old lady from Peoria as much as the hippie in San Francisco, editorial tends toward the conservative.

Does an influx of liberality mean the content is improved? Let's read the latest issue of F&SF and find out!

The issue at hand

by Ed Emshwiller

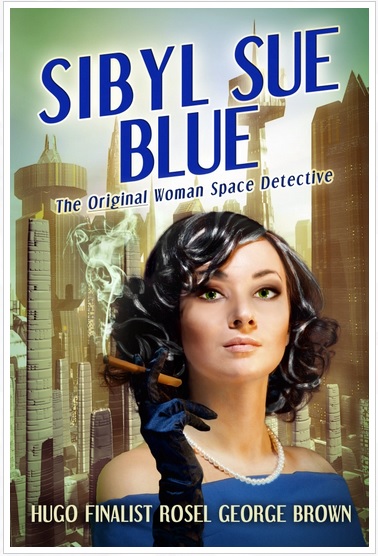

They Are Not Robbed, by Richard McKenna

Richard McKenna died three years ago, but his rate of publication has, if anything, increased. His latest story maintains the quality of work that made his loss so much mourned.

The setup: about 15 years from now, aliens arrive and solve our energy crisis. They also set up cultural exchanges, but the the transactions have a seemingly sinister component. Folks with a certain prerequisite are able to go inside, disappearing for a while before returning with a large check in hand. Aldous Huxley is one of the more famous transactees, but their numbers grow and grow.

Over time, it is determined that each of the selected humans has a certain "tau factor" that has an unknown effect on their behavior and powers. It is only known that the tau factor is measurable…and that it is gone once the humans come back.

Normal humans (those without the tau factor) become jealous, enforcing increasingly rigid restrictions on the tau-enabled humans, with ghettos a foreseeable future. Meanwhile, exchange after exchange begins to disappear.

Amidst this backdrop, we are introduced to our hero, Christopher Lane. Already half dropped out from society, he learns that he is blessed with the tau factor, and upon entering an exchange, learns that it enables him to step out of phase with time. This gives him access to a fairyland world divided into little islands of time. There he meets his true love and hatches a plan to sever his ties with the old Earth before the last exchange closes forever.

As for the sex content, much is made of pulchritude of Christopher's vapid and Earthbound girlfriend (we even learn the color of her pubic hair: black). In this case, the focus on mechanical, unsatisfactory love-making is contrasted with the more elevated relations Chris enjoys out of time.

Only barely science fiction, it is nevertheless a good read. Four stars.

The Turned-off Heads, by Fritz Leiber

The issue takes a bit of a tumble with the next short-short. This exploration of pop culture and the evolving relation of mankind to machinekind is affectedly outré and rather pointless. At least it's short, and I suppose Leiber gets points for forecasting fashion.

Two stars.

by Ed Emshwiller

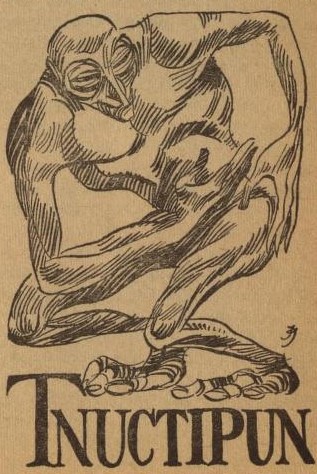

I See a Man Sitting on a Chair, and the Chair Is Biting His Leg, by Harlan Ellison and Robert Sheckley

Here's a piece that reads like it could have been in Dangerous Visions. I'm not sure how much was written by Ellison and how much by Sheckley, but it definitely reads like a fusion of their styles.

Our "star" is Joe Pareti, a man whose prime distinction from the rest of the Earth's teeming, over-educated billions is his ability to harvest "goo." This gray, mucousy sludge has choked the planet's oceans and now provides humanity's main source of food. It also has an alarming tendency to writhe, occasionally forming itself into grotesque parodies of animal life.

The goo also, on rare occasion, infects its harvesters. In an act of carelessness, Pareti succumbs, losing all of his hair overnight. His doctor warns that greater changes may be in store, but given that only six cases preceded Joe's, all of them wildly different in their courses, nothing more can be determined.

It doesn't take long for Joe to find out. In short order, every woman finds him irresistible. A life of increasingly exotic sexual escapades is frustrated when inanimate objects also start to make advances on the former goo farmer. Will he succumb to their inorganic advances? What happens if he says no?

This is a weird piece. But, like most things by Ellison and Sheckley, it's a good piece. Four stars.

Light On Cader, by Josephine Saxton

A young undertaker, bade by his mother's dying wish, climbs Cader Idris in Wales on a raw, misty morning. At the summit, he encounters his life's desire…or maybe an unearthly trap.

That's it. There's really not much to this story–except flavor and texture, which is competently done.

Three star.

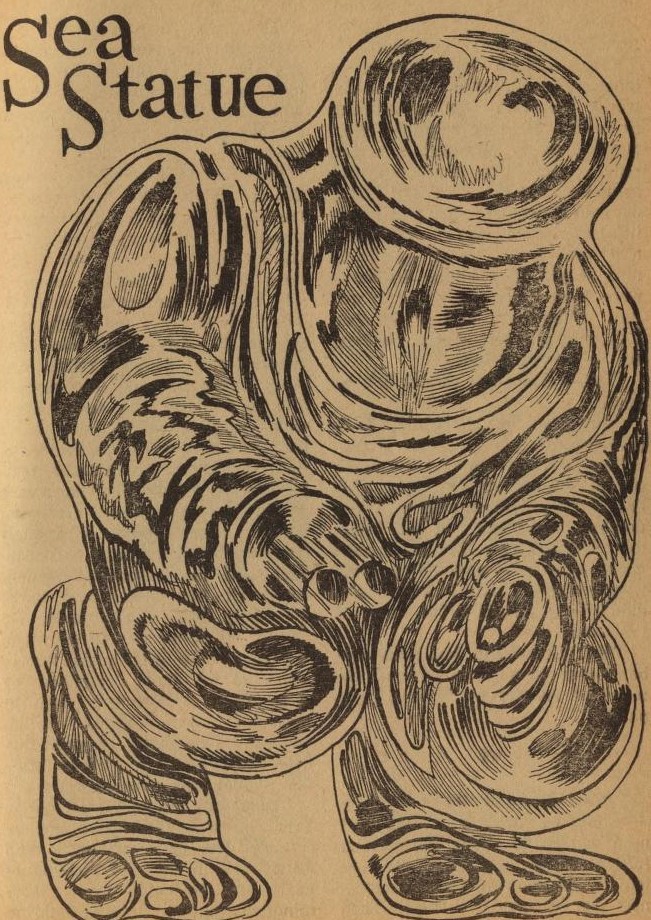

Crack in the Shield, by Arthur Sellings

This UK author offers up a glimpse of life in the 22nd Century. The development of the personal shield, and (for the less wealthy) shields for structures, causes society to fracture into a myriad of animal-totemed clans. Each has laid claim to a province of the economy: Bees make food, Peacocks are in advertising, etc. Assured immortality by falling in line within this strict societal structure, imagination largely disappears.

The only hope for the race lies with those who voluntarily give up their shields. Crack is the story of Philip Tawn, Peacock, who is driven to do just that.

I found this an implausibly optimistic piece, but Sellings writes it well enough. It's also a bit more fuddy-duddy than the rest of the mag, but I suppose balance has its place.

Three stars.

The Seventh Metal, by Isaac Asimov

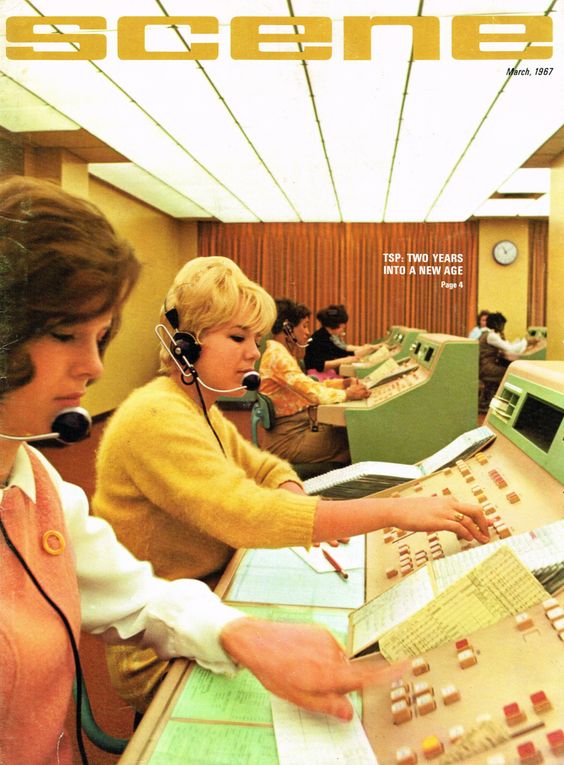

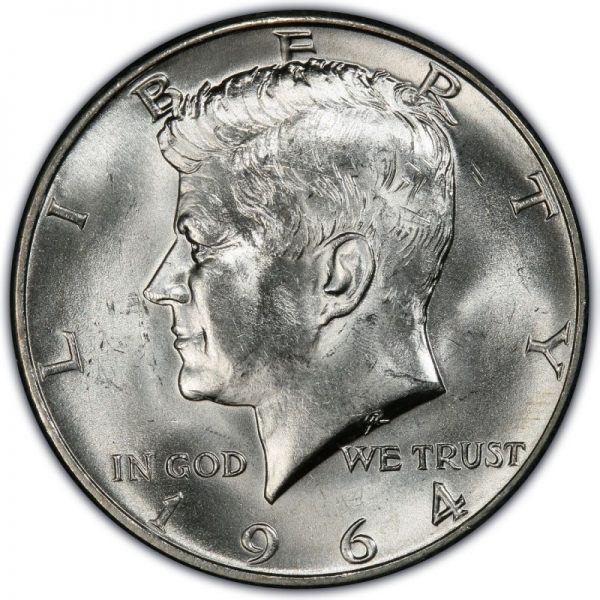

Last issue, I praised Doc A.'s article on the ancient discovery and use of the first seven metals (what a kitschy store in Borrego Springs, where I spent the weekend, described as "the seven mystic metals"). Left undiscussed in that piece was mercury, remarkable among the first seven for being the only one that is a liquid at usual temperatures.

Asimov does a fine job talking about element Hg (and why it has that abbreviation). Four stars.

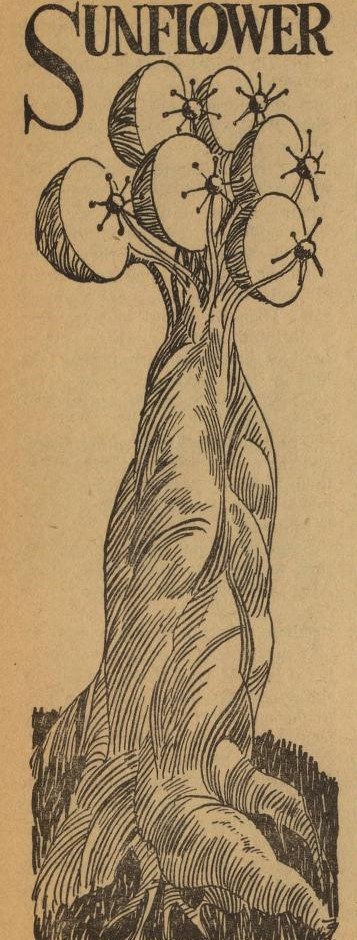

Lunatic Assignment, by Sonya Dorman

Sonya Dorman's tale is of "Four men, dressed in limp white shirts and slacks," each with his own madness. Keepsy, a pervert who sleeps with his hand on his crotch, has a maelstrom of a mind, betrayed all the more by his frustrated desire to project normalcy. Arrigott, having no sense of ego, has trouble with the word "I". Fomer is a schizoid, an empty vessel. And Braun, their leader, has barely suppressed desires to rape and ravage.

But the world is an asylum, and someone has to run it.

I can't say I quite understood this piece, but it is memorable. Three stars.

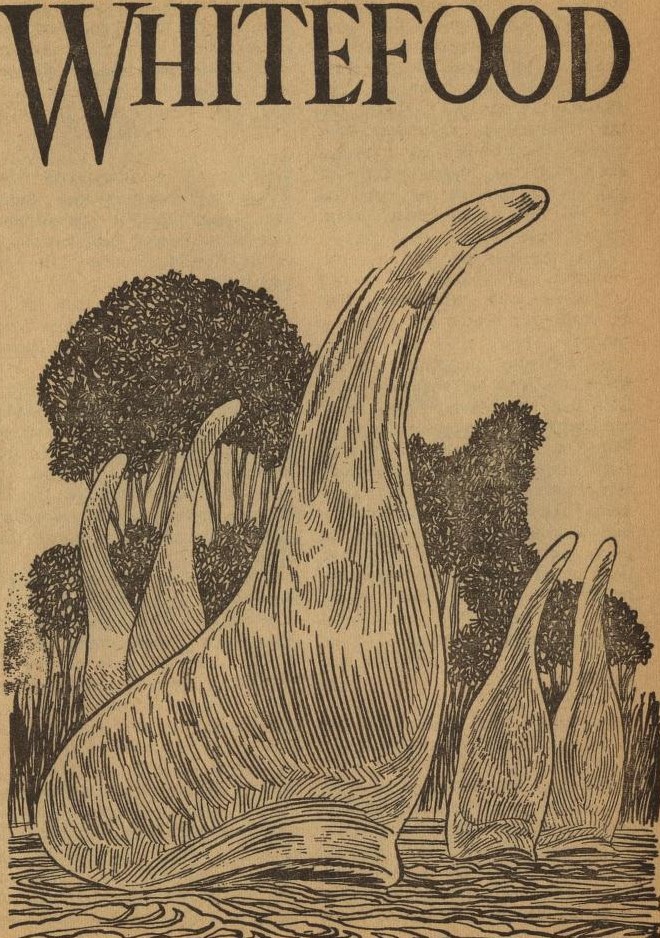

In His Own Image, by Lloyd Biggle, Jr.

by Ed Emshwiller

Lastly, we have the tale of Gordon Effro, a spacewrecked sinner who ends up at a lifeboat station at the edge of space. He washes up at a station inhabited by a mad proselytizer with a coterie of robotic disciples. All Effro wants to do is drink himself blind until the rescue ship arrives, but the wild-eyed Christian has other plans.

I liked this story quite a lot up to its conclusion. There are a number of ways this story could have ended. Biggle chose perhaps the least satisfying, the most conventional.

Thus, three stars.

Can I open my eyes?

As it turns out, the stories with smut were my favorites. However, I don't think their salacious content was what sold me; rather, they were just the most interesting of the pieces. On the other hand, perhaps McKenna and Ellison/Sheckley were able to write so effectively because they felt less fettered when they produced these pieces.

I guess only time will tell if 1967 marked an experimental flirtation with sex in science fiction…or if it presaged an SFnal revolution!

![[December 20, 1967] Smut! (January 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671220cover-672x372.jpg)

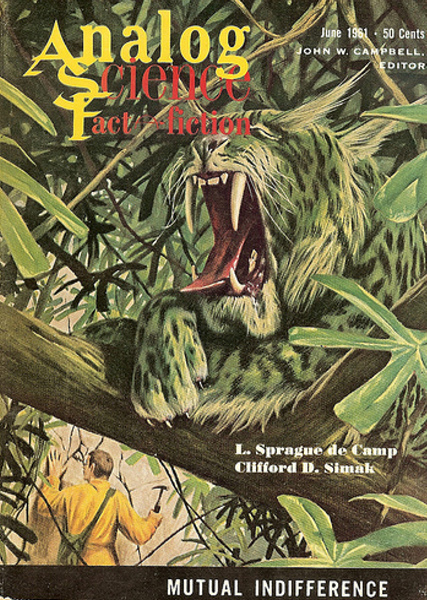

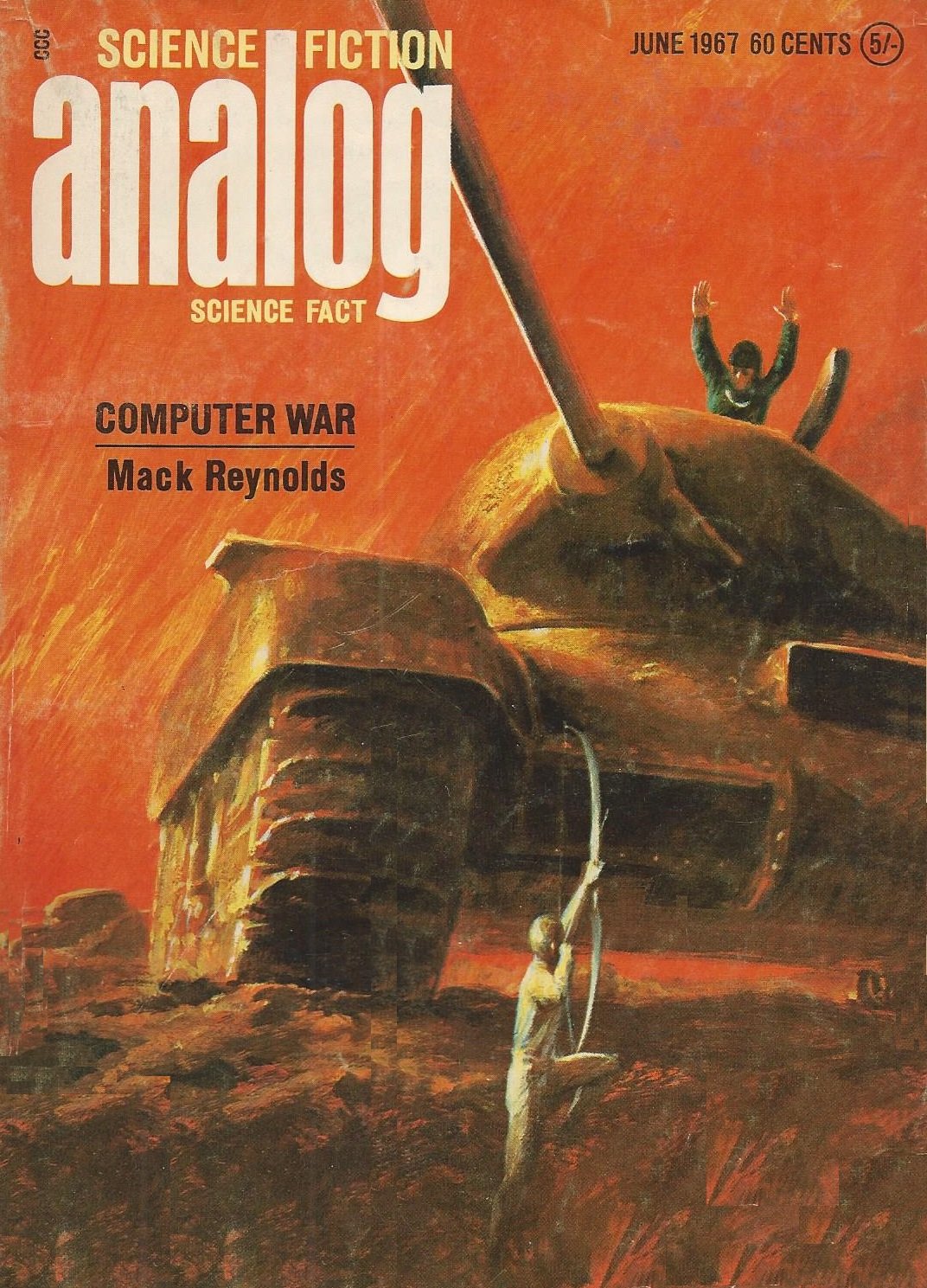

![[May 31, 1967] Phoning it in (June 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670531cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 8, 1966] A Leaden Kind of Fluff (<i>Watchers of the Dark</i>, by Lloyd Biggle, Jr.)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/watchers-cover-512x372.png)

![[April 16, 1966] Non-taxing (May 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660416cover-664x372.jpg)

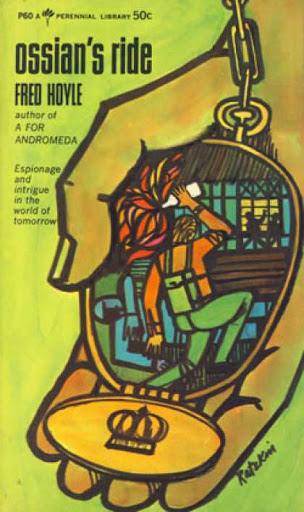

![[April 14, 1965] Furious Time Travel (April Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650414coversnew-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1965] The Big Picture (March 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v02n06_1965-03_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1963] Science Experiments (November 1963 <i>F&SF</i> and a space update)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631020cover-672x372.jpg)