by John Boston

Two Weeks in Philadelphia

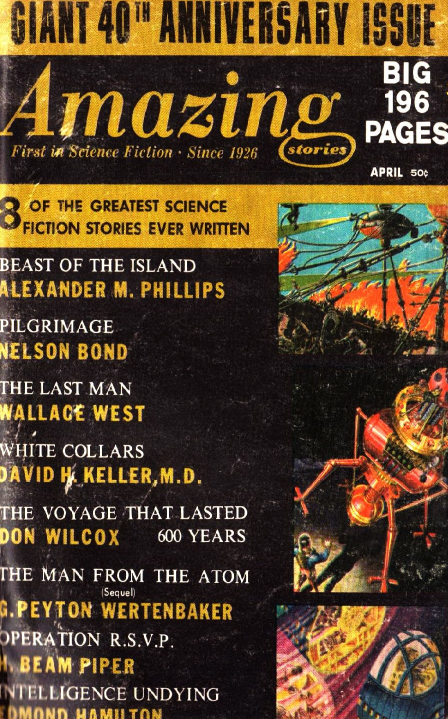

“GIANT 40TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE”

“BIG 196 PAGES”

These are the blurbs on the cover of the April Amazing. Yeah, and W.C. Fields said, “Second prize is two weeks in Philadelphia.” After February’s dreary procession of the better forgotten from Amazing’s back files, the promise of an all-reprint issue with 32 more pages is dubious at best. The architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe likes to say, “Less is more.” We are about to test the converse hypothesis.

by Frank R. Paul, Robert Fuqua, and Hans Wessolowski

But first, the setting for this diamond. You see the drab cover, with the collage of tiny reproductions of early Amazing covers crowded to the edge by a bulldozer of type. Inside, besides the fiction, there is Hugo Gernsback’s editorial from the first issue of Amazing, no more interesting than you would expect, and a two-page letter column, which unlike prior columns includes a letter critical of the reprint policy. More interesting and commendable is A Science-Fiction Portfolio: Frank R. Paul Illustrating H.G. Wells, seven pages of illustrations from early issues of Amazing featuring Wells reprints.

But onward, to the fiction. To begin, or to warn, I should note that much of this issue is dedicated to Big Thinks: the fate of humanity, the proper roles of the sexes in human society, and . . . class struggle!

Beast of the Island, by Alexander M. Phillips

Things begin reasonably well, and not too grandiosely, with Alexander M. Phillips’s Beast of the Island, from the September 1939 Amazing. A couple of guys are plane-wrecked on an uninhabited Pacific island and discover there seems to be some large animal snuffling around—an animal that can talk, or try to. On exploration, they find a cave, complete with ancient skeleton and trunk, which contains a journal detailing the failed struggle of some 17th century sailors to survive the attacks of this terrible beast, foreshadowing their own struggle. This is a quite competent adventure story and the ultimate revelation of the nature of the beast (not to coin a phrase) is reasonably clever for its time. Three stars.

by Robert Fuqua

The mostly-forgotten Phillips first appeared in Amazing in 1929 and published about a dozen stories in the SF/F magazines, the last in 1947. Best known of these is probably his fantasy novel The Mislaid Charm, published first in Unknown, then in hardcover by Prime Press, one of the early SF specialty publishers. He is also that unusual figure, a pro turned fan, having become a mainstay of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society, which did not exist when he started writing.

Intelligence Undying, by Edmond Hamilton

Edmond Hamilton’s Intelligence Undying, from the April 1936 issue, is in equal measure splendid and ridiculous. The brilliant but elderly Doctor John Hanley, frustrated because life is too short to complete all the work he has imagined, has a solution: he orders up a newborn infant (prudently, a “white male child”) from the legions of abandoned children, and decants the contents of his brain into the child’s. (Never mind that old country saying about trying to put ten pounds of . . . whatever . . . into a five-pound bag.) This kills the old Hanley, but he has named a young graduate student friend to be the child’s guardian.

That is an interesting set-up, but Hamilton immediately abandons it. We flash forward to John Hanley the 21st, interrupted in his laboratory in the year 3144 because the rocket ships of the Northern and Southern Federations are fighting. (“The fools, the blind fools! After I’ve worked a thousand years and more to give them greater and greater powers, and they use them—.”) Soon enough the victorious Northerners show up to “protect” him, so he immobilizes them and the rest of the world by activating a device that disturbs their semi-circular canals so no one can stand up. Hanley announces to the world that nations are abolished and he will be ruling them now. Wounded, he orders the Northerners to go immediately and pick him up another male child.

by Leo Morey

Flash forward again to John Hanley 416, or the Great Jonanli, as he is worshiped worldwide. The world’s population is idle, supported by the great automated factories Jonanli has established. But now, he announces to the world, he has discovered that the Sun is about to collapse, rendering Earth uninhabitable. There is nothing for it but to move to Mercury! “There was stunned silence and then from the view-screens came back to him a tremendous, wailing outcry of terror. ‘Save us, Jonanli! Save us from this death that comes upon us!’ ” He tells them that they’ve got to do some work to save themselves but just gets more wailing in return.

So the Great Jonanli reprograms (as our great scientists would put it today) all the auto-factories to crank out robots to build the spaceships, give Mercury some rotation (it was not known in 1936 that it does rotate), terraform it (as we put it today), build cities, and start plants growing. “The humans of Earth helped in none of this but lay supine in terror, crying out constantly to Jonanli and staring in terror at the sun.”

As the sun visibly falters, Earth’s population is ushered onto the spaceships, ferried to Mercury, and dumped there by the robots, who then destroy themselves. John Hanley stays on Earth awaiting the end and dies buried in snow, having learned his lesson, leaving humanity to figure out once more how to take care of itself.

Technological progress leading to stagnation and rebirth (or the lack of it) is of course one of the great themes of SF, both its regular practitioners and drop-ins like that E.M. Forster guy. Here Hamilton renders it with studied crudeness, a comic book without the pictures, terror and majesty pitched to the guy reading the racing form on the subway, forget the Clapham omnibus. Three stars for this absurd tour de force.

Woman’s Place

Two of the stories courageously address the question that haunts . . . somebody’s . . . mind: what is to be done about women—and before it’s too late! Two tales of women-dominated societies probe this urgent question.

The Last Man, by Wallace West

Brightness falls from the air in Wallace West’s The Last Man (from the February 1929 issue); all ridiculous, no splendor, Sexists in the saddle, bad taste in mouth. In the far future, men have been abolished. “The enormous release of feminine energy in the twentieth to thirtieth centuries, due to the increased life span and the fact that the world had been populated to such an extent that women no longer were required to spend most of their time bearing children, had resulted in more and more usurpation by women of what had been considered purely masculine endeavors and the proper occupations of the male sex.

by Frank R. Paul

“Gradually, and without organized resistance from the ‘stronger’ sex, women, with their unused, super-abundant energy, had taken over the work of the world. Gradually, complacent, lazy and decadent man had confined his activities to war and sports, thinking these the only worth-while things in life.

“Then, almost over night, it seemed, although in reality it had taken long ages, war became an impossibility, due to the unity of the nations of the earth, and sports were entered into and conquered by the ever-invading females.”

Artificial reproduction was developed and “the men were dispensed with altogether,” except for a few museum specimens. Later: “In the ages which followed, great physiological changes took place. Women, no longer having need of sex, dropped it, like a worn-out cloak, and became sexless, tall, angular, narrow-hipped, flat-breasted and un-beautiful.”

So here we are with M-1, the Last Man, physically a throwback (i.e., pretty hunky), who lives in a (rarely visited) museum with a caretaker, and is obliged to put himself on display in a glass cage one day a week for the benefit of women who want to gawk at this freak. These women are “narrow-flanked flat-breasted workers, who stood outside the cage and gazed at him with dull curiosity on their soulless faces.”

But there’s an exception—an atavistic woman, conveniently telepathic, who shows up one night outside the glass cage, having slipped away from her keepers: “Hair red as slumberous fire—eyes blue as the heavens—a face fair as the dream face which sometimes tortured him.” Later: “her face assumed a faint pink tinge which puzzled him, yet set his pulses throbbing.” She calls herself Eve, and of course decides to call him Adam. M-1 is horrified and fascinated, and slowly comes around to her rebellious point of view as she shows him around and takes him covertly to the birth factory, which has replaced cruder forms of reproduction. Eve broaches the idea that they might escape and restart humanity the natural way. They are discovered, flee, and Eve hides in the museum and shares his rations.

In the museum, they find a large quantity of TNT, and hatch their plot to destroy the birth factory. Afterwards, as they escape in a flying car, heading for the mountains, “the first rays of the rising sun splashed into the cockpit a shower of pale gold,” and never mind that they have just destroyed the prospects of a society of millions of people, like it or not.

So: women, if they don’t have to spend all their time minding children, will take over the world of work, and then somehow push men out of the world of sport (“sports were entered into and conquered by the ever-invading females”), and kill almost all of the men, and then (despite the earlier talk of “feminine energy”) create a stagnant, joyless, and regimented world in which progress has ceased and all but a few must spend twelve hours a day in tedious labor. Whoa! Guess we better keep them barefoot and pregnant! Sounds like the author’s unconscious taking out its garbage. One star, and a coupon good at any psychiatrist’s office.

Pilgrimage, by Nelson Bond

Nelson Bond’s Pilgrimage offers a more genial take on the evils of matriarchy—that is, with less unalloyed misery on display than in The Last Man. This story is said to be revised from its first appearance as The Priestess Who Rebelled in the October 1939 Amazing.

by Stanley Kay

Civilization has fallen, and in the Jinnia Clan (not far from Delwur and Clina), the Clan Mother is in charge—of the warriors, with (like Wallace West’s future women) “tiny, thwarted breasts, flat and hard beneath leather harness-plates”; the mothers, the “full-lipped, flabby-breasted bearers of children . . . whose eyes were humid, washed barren of all expression by desires too often aroused, too often sated.” Then there are the workers: “Their bodies retained a vestige of womankind’s inherent grace and nobility. But if their waists were thin, their hands were blunt-fingered and thick. Their shoulders sagged with the weariness of toil, coarsened by adze and hod.”

And there are the Men, with their “pale and pitifully hairless bodies,” not to mention their “soft, futile hands and weak mouths”; apparently they are in short supply and excluded from all useful activity except breeding. There are also Wild Ones, rogue unattached males who want nothing more than to get their hands on Clan women and have their way with them. They are sometimes recruited to join Clans, but their supply is dwindling too.

Our heroine, young Meg, has just hit puberty, and doesn’t much like the prospects she sees around her. Nothing will do but to be a Clan Mother herself. And with no hesitation, the wise and learned Clan Mother takes her on. Meg learns “writing” and “numbers” and is introduced to “books.” But before she’s ready to roll as a Clan Mother, she’s got to go on her Pilgrimage to the Place of the Gods, far west and to the north. She’s made it past the “crumbling village” of Slooie and into Braska when she is attacked by a Wild One, but saved by someone unexpected—Daiv of the Kirki tribe, “muscular, hard, firm,” who quickly tells her twice that she talks too much, and suggests that she mother a clan with him.

Daiv is quickly dismissed, and Meg sets out again, on foot, because her horse ran away during the affair of the Wild One. But Daiv shows up again and introduces her to “cawfi,” and also to kissing. “Suddenly her veins were aflow with liquid fire.”

At last, after the long journey northwest from Jinnia, she arrives at the Place of the Gods, and there they are: “stern Jarg and mighty Taamuz, with ringletted curls framing their stern, judicious faces; sad Ibrim, lean of cheek and hollow of eye; far-seeing Tedhi, whose eyes were concealed behind the giant telescopes.” The Gods are Men! Real men, like Daiv! What to do? Return to the sterile and diminishing life of the Clan? No! She heads “back . . . back to the fecund world on feet that were suddenly stumbling and eager. Back from the shadow of Mount Rushmore to a gateway where waited the Man who had taught her the touching-of-mouths.”

This of course makes very little sense, to send the Clan Mother-in training off on a pilgrimage that will undermine the entire basis of the society she is supposed to preside over, but that lapse of logic would seem to be beside the author’s urgent point. Two stars; it’s less unpleasant than The Last Man.

White Collars, by David H. Keller

White Collars, by David H. Keller, M.D., from the Summer 1929 Amazing Stories Quarterly, is a social satire, of sorts. Keller was known for absurd extrapolation. His most famous story may be Revolt of the Pedestrians, in which humanity has evolved, Morlocks-vs.-Eloi style, into automobilists (of cars and powered wheelchairs), whose legs have atrophied, and back-to-nature pedestrians, and of course they struggle for supremacy.

by Hynd

Here, the trend towards more education for everybody has resulted in a huge oversupply of the college and professional school graduates, who are all too ready to remove your tonsils or teach you Greek, if only more people needed those services. These White Collars, who are on the march with picket signs as the story opens, demand employment fitting their educations, and refuse to perform any of the practical work that is actually needed or accept the decline in social status that would go with it. They’d rather live in desperate but genteel poverty and complain about it.

The story consists largely of conversations between Hubler, a millionaire plumber, and Senator Whitesell, who is in the dam-building business but (as he puts it) “bought a seat in the Senate,” encouraged by his business associates, who “felt that our group was not being properly cared for.” (It’s hard to tell if this too is satire, or if everyone was a little less subtle about these things in Keller’s day.) Hubler takes Whitesell on a tour of the White Collars’ neighborhood, including a visit to the Reiswicks, the family whose daughter Hubler’s son is in love with. The family will have none of an offer of productive but lower-status work and the daughter will have nothing to do with the son of a plumber.

Senator Whitesell goes back to Washington, and the general problem is resolved with draconian legislation providing for involuntary servitude, complete with labor camps, and suppression of criticism. This does wonders for formerly idle intellectuals: “They became different men and women, they sang at their work, and the number of babies born in the Labor Hospitals to happy mothers and proud fathers steadily increased.” The private problem of the Reiswicks is solved by a combination of emigration and the last-minute kidnapping and forced marriage of their daughter to the plumber’s son—but she decides she likes the idea after she sees his modern kitchen.

This of course is all mean-spirited and reactionary, as well as ridiculous, but hey, it’s satire, though Keller is no Jonathan Swift. (And I wonder what Keller had to say a few years later about the New Deal.) Keller is at least a competent writer. So, two stars, barely.

Operation R.S.V.P., by H. Beam Piper

by Robert Jones

Between West and Keller, we have a brief respite from gravity in H. Beam Piper’s Operation R.S.V.P., from the January 1951 issue, which presents the lighter side of the struggle for world domination. Piper at this point had published several solid and well-received stories in Astounding, still one of the field’s leaders. This one is flimsier: an epistolary story, told in memos among the Union of East European Soviet Republics and the United People’s Republics of East Asia, which are engaging in nuclear saber-rattling, and Afghanistan, which is outsmarting them both. It is clever and well-turned and not much else; it aspires to little and achieves it handily. Two stars.

The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years, by Don Wilcox

Don Wilcox, whose actual name is Cleo Eldon Wilcox, but who has also appeared as Buzz-Bolt Atomcracker (in Amazing, May 1947, for Confessions of a Mechanical Man), published SF from 1939 to 1957, almost entirely in Amazing and its companion Fantastic Adventures, mostly in the Ray Palmer era. The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years, from October 1940, is a fairly well-known if not much-read story, chiefly because it was the first to explore the idea of a generation starship, preceding and possibly inspiring Robert Heinlein’s much more famous Universe.

by Julian Krupa

The good ship S.S. Flashaway carries 16 couples, plus the narrator, Prof. Grimstone. He will serve as Keeper of the Traditions, traveling in suspended animation and being revived every hundred years to keep things on track, handily providing a viewpoint character for this centuries-long story. Upon his first revival, he hears many babies crying; there is a population crisis. Why? Boredom, apparently. Grimstone suggests wholesome activities: “Bridge is an enemy of the birthrate, too.” But alas: “The Councilmen threw up their hands. They had bridged and checkered themselves to death.”

Solutions? One character says, “We’ve got to have a compulsory program of birth control.” Prof. Grimstone in his recommendations “stressed the need for more birth control forums.” Not to be indelicate, but I don’t think people trying to avoid pregnancy use a forum. And you’d think the people planning this trip would have made some provision for it—maybe even something futuristic, like, oh, a pill that would suppress ovulation or fertilization. But I guess you couldn’t really talk much about that in a family magazine in 1940.

So, leap forward 100 years, and Grimstone awakes to find people lying around starving. Babies are still the problem. These people were born outside the quota, and by decree are not allowed to eat regularly. Grimstone sets matters straight: everybody eats, there’s a new regime, everybody outside the quota is surgically sterilized, and inside the quota they’re sterilized after the second child. And they’re all happy about it.

A century later, there’s no population problem, but factions are at each other’s throats, and Grimstone has to make peace. And it goes on, century by century. Wilcox has put his finger on the central problem of the generation ship idea: there’s no reason for the intermediate generations, who didn’t sign up for life in a big tin can and have nothing else to look forward to, to remain loyal to the mission and to keep the discipline necessary for a small community to survive for centuries.

There’s a pretty decent story here, unfortunately swathed in wisecracking Palmerish pulp style—the first line is “They gave us a gala send-off, the kind that keeps your heart bobbing up at your tonsils,” and that’s pretty representative. It’s also weighed down by the taboos of the time in the overpopulation episode. Wilcox gives the impression of a writer of limited gifts struggling to do justice to a substantial theme, which is both refreshing and frustrating. Three stars, for effort and for originality in its time.

The Man from the Atom (Sequel), by G. Peyton Wertenbaker

The issue closes with G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s The Man from the Atom (Sequel)—yes, that’s the title—from the May 1926 Amazing. You will recall that the narrator Kirby was invited over to Dr. Martyn’s place to try out his expander/contractor, pushed the Expand button like any good SF mark-protagonist of the 1920s and ‘30s, and found himself growing so large that his feet slipped off Earth and he wound up in a super-cosmos in which our universe was but an atom, trillions of years in the future. He’s not thrilled about it, either.

by Frank R. Paul

But he works the Shrink button and gets himself sized to land on another planet, thrusting his feet through the clouds as he downsizes. There he falls into the hands of supercilious humanoids who imprison and interrogate him, but shortly the beautiful Vinda—daughter of the King of the planet, of course—shows up, providing “endless days of wonder and enchantment” (not biological, we are assured), and also offering a way back. Well, not exactly back. The way back is forward, because (after invocation of Einstein and the curvature of space), “the whole history of the universe is rigidly fore-ordained, and so, when time returns to its starting point, the course of history remains the same.” More or less, anyway.

So the humanoids make some calculations, he pushes the Expand button again, and before long arrives on (a slightly different) Earth, only to learn that Dr. Martyn has been imprisoned for murder after his disappearance, or rather, the disappearance of the corresponding Kirby in this world. Now he's released, of course. But after a while, home, or near-home, is not enough for Kirby; he pines for Vinda; and soon enough he is pushing the Expand button again, hoping to rejoin her in the next cycle of the universe, even if he has to fight the other version of himself that this cycle’s Dr. Martyn has previously dispatched.

This sequel is a noticeably higher class of ridiculous than its forerunner, better written and with considerably more ingenuity of detail along the way, so it laboriously climbs to two stars.

And I Only Am Escaped Alone To Tell Thee

Well, it could have been worse. Two of these stories, Beast of the Island and, barely, The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years, are actually worth reading for reasons other than laughs or historical interest. The rest are not, except for the overdone spectacle of Intelligence Undying.

[Don't miss TODAY'S episode of the Journey Show, starting at 1:00 PM Pacific — we have an all star cast of artists who will be doodling to YOUR specification.

Y'all come!]

![[April 16, 1966] Non-taxing (May 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660416cover-664x372.jpg)

![[April 14, 1966] A New & Clear Bombshell (<i>The War Game</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/War-Game-1a.jpg)

![[April 8, 1966] Search Parties (May 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Fantastic_v15n05_1966-05_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

![[March 31, 1966] Shapes of Things (April 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660331cover-500x372.jpg)

![[March 28, 1966] Typhoid Doctor (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Ark)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660328monoid-672x372.jpg)

![[March 22, 1966] Summer in the sun, winter in the shade (April 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 14, 1966] Random Numbers (May 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n07_1966-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

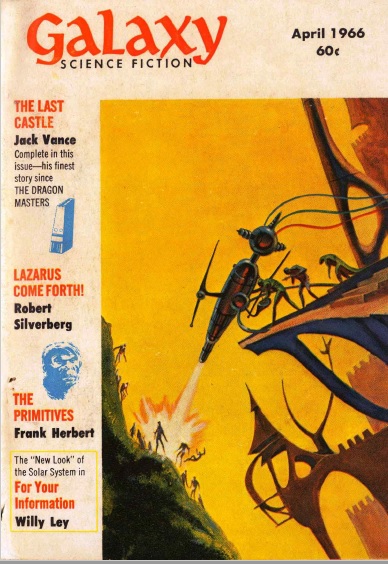

![[March 10, 1966] Top Heavy (April 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660310cover-388x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1966] Is More Less? (April 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/amz-0466-cover-448x372.png)

![[March 4, 1966] Sanguinary Cinematic Surgery (<i>Blood Bath</i> and <i>Queen of Blood</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660304movie-600x372.jpg)