by John Boston

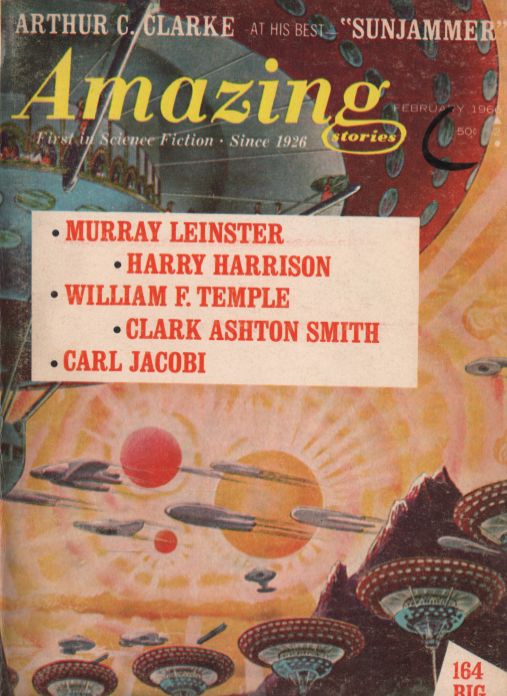

Slog Through the Bog

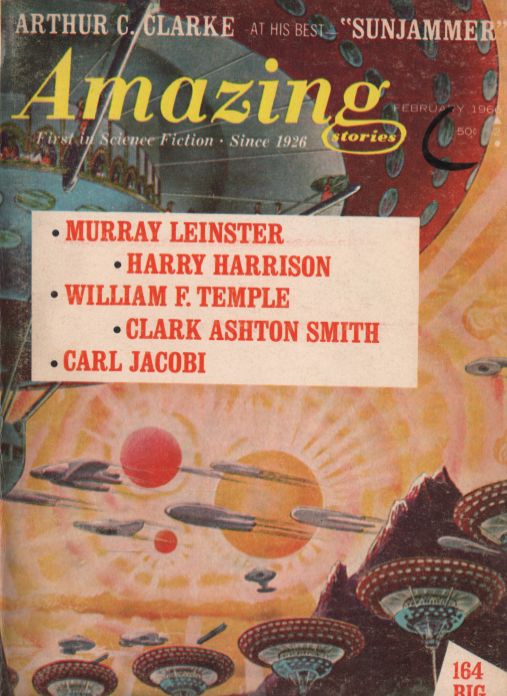

Publisher Sol Cohen’s policy of filling his magazines with reprints from older issues continues and solidifies in the February Amazing. All but two of the stories here are reprints (though some did not originate in Amazing). The cover is a reprint too! This vague and busy image titled Mizar in Ursa Major is from the back cover of Fantastic Adventures—Amazing’s companion fantasy magazine—for May 1946, by Frank R. Paul, long past his prime by then.

by Frank R. Paul

Other contents are limited to an editorial by Cohen that is so incoherent I won’t even try to recount his point, and another one-page letter column mostly praising Cohen’s “revitalization” of the magazine “in the old-time tradition” and rejection of the “obscure and often affected themes” of other magazines. Also, somebody is looking for Jerry Siegel, creator of Superman, in order to make a movie of one of his old stories.

Onward to this mostly grim and laborious adventure.

Sunjammer, by Arthur C. Clarke

by Nodel

The issue opens with Arthur C. Clarke’s Sunjammer—a reprint from, of all places, Boys’ Life, the Boy Scouts magazine, in 1964. It’s about a race to the Moon among vessels propelled by light pressure from the Sun on diaphanous sails hundreds of miles in area. It’s not bad—Clarke doesn’t know how to be bad—but it reads a little too much like a lecture on practical astrophysics, and is much less lively than the last recent Clarke story I read, The Shining Ones, in the Judith Merril annual anthology. Maybe Clarke thinks that writing for young people means he has to be more overtly educational than usual. It’s reminiscent of his slightly pedantic Winston juvenile of the early ‘50s, Islands in the Sky. Three stars.

[This is also what Mark Yon gave it when it came out last year in New Worlds (ed.)]

For Each Man Kills, by William F. Temple

After Clarke, things get overripe fast. William F. Temple’s For Each Man Kills is from the March 1950 Amazing, right after editor Ray Palmer’s regime of “gimme bang-bang” ended. Suddenly under new editor Howard Browne there was a sprinkling of more respectable bylines among the house pseudonyms, among them Kris Neville, Ward Moore, Fritz Leiber, and Temple—unfortunately, not bringing much improvement, at least in this case.

In For Each Man Kills, protagonist Russ is waiting for his inamorata Ellen Carr to finish dressing, in a room full of pictures of her. Looking at a portrait, he thinks: “Da Vinci himself couldn’t have put all of Ellen on canvas.” There are a lot of photos, too, but “He realized at once that no photo could ever remotely compensate for her physical absence.” At this point I was tempted to burst into song: “It would take, I know/A Michaelangelo/ . . .to try and paint a portrait of my love.” But I resisted, and carried on. Just as well, it’s a doozy.

This one-remove ogling is taking place in Pinetown, a town probably in the US, surrounded by desert, and further isolated by an impassable radioactive zone after a nuclear war. (Pinetown? Surrounded by desert? Never mind, move on.) Russ is the Mayor’s right-hand man in trying to rebuild after the war’s destruction. He asks Ellen to marry him. But she turns him down. She’s been swotting atomic theory and her application has just been granted to go work on the radiation-leaking atomic pile outside town. A side effect of radiation exposure is that women turn into men. He sees her home, beating up a guy who tries to molest her along the way.

by Leo Summers

The guy shows up next day and shoots at Russ, killing the Mayor instead. Now Russ is the Mayor, working 18-hour days to restore Pinetown to something like its pre-war condition. At the atomic pile, there’s no Ellen Carr any more, just a young Alan Carr; Ellen has changed sex, as feared. Russ’s eye then falls on Maureen, 18, “petite, dainty, uncomplicated.” Before long they are engaged. But then—Maureen turns up with leukemia. And who knows the most about how to deal with it? The young man from the pile, Alan Carr, who treats her with radioactive phosphorus. Before long, Maureen is getting better, but asks Russ to break the engagement. She’s in love with Alan Carr. “The two girls he wanted to marry ended up marrying each other!”

Russ goes home and gets drunk for a week, and comes back to hear that the pile is almost out of fuel. But there’s an unexploded atomic rocket in the radioactive belt around Pinetown. Russ dispatches the most knowledgeable person, Alan Carr, to retrieve it so they can exploit it for fuel and keep Maureen in radioactive phosphorus. But the rocket blows up, killing Alan, and Maureen is on her deathbed. She tells Russ that Alan had told her to forget him and devote herself to Russ, then she dies. Meanwhile, Russ has been given a letter, which proves to be from Alan, confessing to being a narcissistic personality and explaining his (her) conduct before and after the sex change. There’s a buzz in the sky and an airplane appears; Pinetown’s isolation is over. “Life was beginning for Pinetown. It had ended for its Mayor.”

At this point the story’s provenance becomes clear. Temple thought that he had spotted a marketing niche, and tried to sell US radio, and what there was of TV, on something new—a post-atomic soap opera! And he wrote this story to salvage something from his labors when they laughed him out of their offices. Two stars, barely, and an overwrought sigh, organ music swelling in the background.

The Runaway Skyscraper, by Murray Leinster

The Runaway Skyscraper is Murray Leinster’s first known SF publication and appeared in the February 22, 1919, issue of Argosy and Railroad Man’s Magazine, as that famous old publication was known for five months or so. Here it is attributed to the third issue of Amazing, June 1926, where it was first reprinted. It’s actually a bit of a revelation after the longueurs of Leinster’s recent serial Killer Ship. A New York office building containing 2000 people suddenly begins racing into the past, with day and night flickering and clocks and watches running backwards (but not the characters’ alimentary processes or their chonological aging. Go figure.). The building fetches up in the Manhattan wilderness of thousands of years ago.

by Small

What to do? Protagonist Arthur Chamberlain, along with the other sound go-getters among the menfolk, and assisted by his secretary the attractive Miss Woodward, calm the crowd, address the immediate problem of feeding 2,000 people (fortuitously assisted by passenger pigeons fatally colliding with the building’s windows) and setting up comfortable separate quarters for the women (men? They can sleep on the floor somewhere). It’s like The Swiss Family Robinson—never any serious danger, solutions present themselves almost as soon as problems appear. This is all interspersed with the charmingly clumsy romance of Arthur and Miss Woodward, who are married by the end. Overall, it’s quite a well executed piece of light entertainment—not surprising, since by this time Leinster had already published several dozen stories in magazines with titles like Snappy Stories, Saucy Stories, and Breezy Stories.

But (of course there’s a but). The skyscraper alights right across the not-yet-existent Herald Square from an Indian village, complete with “brown-skinned Indians, utterly petrified with astonishment”; when the Office People approach, the Indians flee in terror, abandoning their homes and belongings. They reappear in the story a couple of weeks later, and now they are working for the white folks, providing food mostly in return for trinkets, including a broken-down typewriter, which the “savages” cart away “triumphally.” Born to be simple, apparently.

by Frank R. Paul

It gets worse. After the building has returned to its proper time through Arthur’s scheme of pumping a soap solution into the foundation, it transpires that one tenant, “a certain Isidore Eckstein, a dealer in jewelry novelties,” made some side deals with the Indians, trading necklaces, rings, and a dollar for title to Manhattan Island, and has now sued all landholders in Manhattan demanding rent from them.

This is a bit malodorous even for 1919 and takes the shine off an otherwise accomplished piece of froth. Two stars, tolerantly.

The Malignant Entity, by Otis Adelbert Kline

by Leo Morey

The Malignant Entity by Otis Adelbert Kline originated in Weird Tales for May-July 1924, but later appeared in Amazing for June 1926, and again in Amazing Stories Quarterly for Fall 1934. It is surprisingly good for most of its length—surprisingly since Kline is best known for his knockoffs of Edgar Rice Burroughs, with titles like The Swordsman of Mars. It’s quite formulaic: Scientist is found shockingly dead in his lab (a skeleton, fully dressed); narrator Evans is conversing with his friend Dr. Dorp when the police ask the doctor to come check out the deceased Professor Townsend, and Evans tags along. The late Prof had been working on the generation of life from dead matter, and it appears he has succeeded too well; the investigation is all too successful, and they are confronted with the eponymous Entity. The story is done primarily in dialogue, with the characters all explaining things to each other, but Kline has a knack for brisk banter with few words wasted, so it moves along nicely. Unfortunately it goes on long enough to overstay its welcome, and gets a bit ridiculous towards the end, sliding down to two stars.

It Will Grow On You

Two of this issue’s stories focus on growth of one sort or another, both sorts to be avoided by the prudent.

The Man from the Atom, by G. Peyton Wertenbaker

G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s The Man from the Atom is credited to the first, April 1926, issue of Amazing, but originated in the August 1923 Science and Invention. That was another of Hugo Gernsback’s magazines, started in 1913 as Electrical Experimenter, changing to Science and Invention in 1923 and continuing to 1931. It published occasional fiction early on, and by 1920 was running one or two stories in each issue. The August 1923 issue, with six stories including Wertenbaker’s, was labelled the “Scientific Fiction Number,” and could be seen as a dry run for Amazing.

by Howard V. Brown

Wertenbaker was one of the early Amazing’s most capable writers; see The Chamber of Life, reprinted during the Cele Lalli regime. Unfortunately, The Man from the Atom is among his juvenilia; he would have been 16 when it was published. It shows. The story is badly overwritten. The opening lines: “I am a lost soul, and I am homesick. Yes, homesick! Yet how vain is homesickness when one is without a home!” The plot is canonical for its time. The narrator’s friend, Professor Martyn, invites him over to try out his new invention, which can shrink or enlarge a person with the push of a button. Shrinkage is possible because “an object may be divided in half forever, as you have learned in high school, without being entirely exhausted.” (They never taught me that in high school. What else are they hiding from me?) Growth is accomplished by extracting atoms from the air, which the machine “converts, by a reverse method from the first,” into atoms suitable for supplementing the various substances of the body.

So the narrator dons what amounts to a space suit, pushes the expansion button, and off he goes, as the Professor hastily drives off to avoid the expansion of the narrator’s feet. As he expands into space, and Earth shrinks to a relative diameter of a few feet, whoops! “My feet slipped off, suddenly, and I was lying absolutely motionless, powerless to move, in space!” Also, so much for the Western Hemisphere, though the author doesn’t mention that. Only after further observation of the wonders of the shrinking heavens, and finding himself on a planet and realizing his world is likely an atom of this one, does he try to go back, retracing his . . . well, not exactly steps . . . but the Sun is not there! He realizes that his growth in size brought an acceleration of time, and home is trillions of centuries in the past. So he fetches up on an available planet. “I live here on sufferance, as an ignorant African might have lived in an incomprehensible, to him, London. A strange creature, to play with and to be played with by children. A clown . . . a savage!”

by Frank R. Paul

Of course all this makes very little sense even in its own terms. For example, expansion is supposedly made possible by converting atoms from the air, but how did the narrator grow beyond the size of the known cosmos with only the atoms in his airtight suit and the small tank of compressed air attached to it? One could go on, but why bother? This relic should have stayed buried. One star.

Moss Island, by Carl Jacobi

Another kind of growth appears in Moss Island, by Carl Jacobi, from the Winter 1932 Amazing Stories Quarterly, but revised from something called The Quest, May 1930. Jacobi was an all-around pulpster through the 1930s and into the ‘40s, but settled into the SF/F/weird magazines by the mid-‘40s, and seems to have mostly hung it up late in the ‘50s. Protagonist goes to do some geological surveying on the island, which is off New Brunswick and inhabited only by trees and other vegetation, Chiseling away, he finds a pocket of mucilaginous (author’s word!) brown stuff, and recognizes it as Muscivol, a substance identified by Professor Monroe at his college (another Professor! Anyone who’s read this far should realize that they always mean trouble). Muscivol contains “all the elements of growth”—a lot of growth. So protagonist fills up his Thermos bottle with the stuff.

by Leo Morey

Pressing into the forested interior, he finds a lot of moss and drips a little Muscivol on it. The moss leaps upward so fast that he trips and spills the Thermos contents. “A great shudder ran through the moss. A sobbing sigh came from its grasses. And then with a roar, the rootlets gouged down into the ground, tore at the soil, and the plant with a mighty hiss raced upward, five feet, ten feet. The tendrils swelled as though filled with pressure, became fat, purulent, octopus folds. Like the undulations of some titanic marine plant the white coils waved and lashed the air. Up they lunged, the growth rate multiplied ten thousand times.”

Protagonist runs like hell, with the moss, expanding like the Man from the Atom, hot on his heels. Fortunately he is able to get down a cliff where his hired boatman is waiting for him, and escapes. The boatman can’t see the giant wall of moss through the fog that has rolled in, so, as usual in stories of this period, the horror is neatly contained. It’s less ridiculous than Wertenbaker’s story, but still formulaic, and undistinguished in execution. Two stars.

The Plutonian Drug, by Clark Ashton Smith

Next, Clark Ashton Smith! A legendary figure in the 1930s Weird Tales pantheon, with H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. However, The Plutonian Drug—from the September 1934 Amazing, Smith’s only story in the magazine—is much more pedestrian than either Smith’s usual extravagant titles (The City of the Singing Flame and the like) or his usual florid style. Balcoth the sculptor is talking with his friend Dr. Manners (not a Professor, but just as dangerous), who discourses at length on interplanetary drugs. He offers Balcoth some plutonium, a drug from Pluto, which he promptly scarfs down, after being assured it will wear off quickly and will not affect his next appointment. (This is obviously not the plutonium that we have learned to know and love; element 94 was not isolated and named until late 1940 or early 1941.) What this plutonium does is lay out the events of one’s past and future in an array in the mind’s eye, past on the left, future on the right. For Balcoth, the right-hand range is very short for no apparent reason, and when he leaves and the reason is revealed, it is neither surprising nor interesting. This story is less obscure than most others in this issue; I was mildly bored by it for the first time in 1958, in the Berkley paperback of August Derleth’s anthology The Outer Reaches. Two stars, barely.

In with the New

Now to the stories that are original with this issue.

Pressure, by Arthur Porges

Arthur Porges’s Pressure is another Ensign De Ruyter exercise in Fun with Fifth-Grade Science, in which the Ensign figures out how to solve the characters’ problem by harnessing the weight of a large quantity of mercury. One star as usual.

Mute Milton, by Harry Harrison

Harry Harrison’s Mute Milton is an SF story about Jim Crow, very simple and not the least bit subtle. A professor—this time, the good kind—at one of the South’s Negro colleges is on his way home by bus, carrying a rather important invention, and has a glancing encounter with the police and the racial attitudes that he has been navigating all his life. He meets another Negro who has aroused even more official ire, and gets fatally in the way when the police catch up to them. The invention gets stepped on. It’s a crude and brutal story about a crude and brutal reality that SF writers generally acknowledge only at arms-length and metaphorically. The only actual reference to contemporary events is to the Freedom Riders, whose activities began and ended in 1961. I’ll bet this story was written then or shortly after, rejected all around, and has only found a publisher now that there’s a new regime at Amazing. Good for them, for a change. Four stars.

Summing Up

Some of the old stuff is well worth reading. This isn’t it. The older reprinted stories are variously stale, cliched, boring, bigoted, and/or nonsensical to one degree or another. You can find something good to say about some of them (how I struggled), but they’re still mostly a waste of time. The best things in the issue are the new story by Harry Harrison and the almost new one by Arthur C. Clarke. If Amazing’s reprint policy were an experiment, at this point I would call it a failure. Unfortunately it doesn’t look like an experiment. The next issue—April 1966, the 40th anniversary issue—will be nothing but reprints.

[We only give you the plum assignments, John! Or perhaps this is a prune… (ed.)]

![[January 12, 1966] La Belle Époque in the Jet Age](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Hommos-and-Kibbeh-at-Byblos-672x372.png)

![[January 10, 1966] Kingdom Come (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Daleks’ Master Plan [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660110hmmmm-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1966] Have Archaic and Beat It Too (February 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/amz-0266-cover-507x372.png)

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1966] God of Time (The Planet Saturn)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/660102saturncard-613x372.jpg)

![[November 16, 1965] Crime and Punishment (January 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n05_1966-01_dtsg0318.Anon_0000-3-672x372.jpg)