by Joe Reid

This week’s episode of Star Trek will likely turn many members of the audience into devout Buddhists. It’s an episode which stands as a reminder of the destructive nature of desire and why the devotees of the Buddha eschew that emotion. “Requiem for Methuselah” showcased a level of desire that proved more contagious and damaging than any infectious fever.

The show started with the Enterprise in orbit of Holberg 917-G, in the Omega system. 3 crew members had died and 23 were sick with Rigelian Fever. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy beamed down the planet in search of ryetalyn, a mineral that could cure the ill.

As they were about to split up to locate the vital substance, a hovering robot reminiscent of Nomad, from “The Changeling”, showed up and fired on them. It rendered their weapons useless and had them cornered until “Do not kill!” was shouted by a voice whose owner was out of view.

"You are the Kirk? The Creator?"

A finely dressed older man with a Caesar haircut revealed himself, demanding that they leave the planet. Kirk and crew would not be deterred and threatened they would take the ryetalyn if they had to. The man, named Flint, said that he could kill Kirk, implying that the crew and the starship were no threat to him. McCoy pleaded with Flint, saying that Rigelian fever was on par with Bubonic plague. This caused Flint to think back to the city of Constantinople and what the plague had done to the people there. Flint relented and allowed the crew to stay, while his flying robot, M-4 (likely unrelated to M-5 from “The Ultimate Computer”), went off to gather ryetalyn. Flint promised that M-4 could gather the materials faster than they could. Being that those who were sick on the Enterprise had only four hours before the disease progressed, McCoy and the others agreed to allow it.

"What else can I get you? A bag of reds? Keys to my Mercedes? An original copy of the U.S. Constitution?

Flint took the trio to his castle. Inside Spock noticed a treasure trove of classic art. Art from DaVinci. Music from Brahms and other fineries. Flint left them alone to enjoy some brandy, after telling them that he lived alone with only M-4 as company, while in another part of the castle, a lovely young woman watched Kirk and the others on a screen.

"I do so love that Johnny Carson!"

Flint entered the room and spoke to the young beauty, named Rayna. She looked on the other men with desire and said she wanted to meet them, since she had never met other people besides Flint.

As M-4 returned with the ryetalyn, Spock continued to marvel at the priceless art pieces housed in the castle, but he also noted that they were created using modern materials and not ancient ones. Flint then entered and sent M-4 away to prepare the ryetalyn, with the promise that it would be completed faster than it could be on the Enterprise.

As an apology for his initial rudeness, Flint introduced Kirk and the others to Rayna, her very presence being as a gift to the men in attendance. At first sight, desire for the beautiful young woman flooded Kirk’s eyes. Flint’s method of apology apparently landed well with Kirk in particular.

Rayna teaches Kirk how to hold his stick

The introduction of Rayna started the main arc of the episode in earnest. Her beauty and intelligence seemed to have stirred something in Kirk rather quickly. She in turn began to explore emotions that she had never felt before due to Kirk’s focus on her.

The desire between Kirk and Rayna was visible and out in the open, whereas Flint was a man filled with deep desires that he protected viciously. The story also revealed him as a man of many secrets, holding so many of them that it was not until we finally learned the truth about him and also about Rayna, that the real danger of the episode took hold.

In the end, the painful desire and vast longing on display in this episode brought one character to complete ruin and threatened to destroy the rest in their wake.

In conclusion, outside of the insane speed at which Kirk falls for Rayna, this episode had an interesting plot and premise. The characters seemed compelling and the type of people that would be tempting to see on adventures of their own. Suffice it to say, that Rayna and Flint didn’t feel disposable to me as other characters often do. Also, the narrative twists and surprises near the end were not overly foreshadowed. They took me by surprise and I appreciated that. Now, if I can just find a Buddhist temple to ensure I remain free of what happened in this episode.

Four stars

What Could Have Been

by Janice L. Newman

“I’m tired of broken episodes,” my daughter said wearily after the credits had finished rolling. I couldn’t help but agree. For the past several weeks, we’ve had frustrating episode after frustrating episode, made all the more dissatisfying because in every case, we can see what could have been.

With shows like Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, the plots are generally silly enough not to be taken seriously. But we’ve seen just how good Star Trek can be, and it’s obvious that the script writers are trying. Sadly the most recent batch of episodes has been filled with poor characterization of our beloved crew, plots that made no sense, stories that tried to Say Something but stumbled over their words, and things that…well…just didn’t feel like Star Trek!

The most recent episode suffered from many of these ailments. For one, it had two conflicting plots: the epidemic on board the ship and the mystery of the old man and his ‘daughter’ on the planet. A competent version of the script would have played these two threads off of each other, keeping the viewers in suspense about whether the captain and his men would be able to bring back the cure in time. But since all three crewmembers treat the epidemic situation casually, it’s hard for the viewers to take it seriously or become invested in it. We never see anyone sick on the ship, so it’s up to Shatner, Nimoy, and Kelley to give us a sense of urgency. Instead, Spock is intrigued by the mystery surrounding Flint and Kirk far too quickly becomes enamored with Rayna. Their constant distraction feels out of character and irresponsible to the point of dereliction of duty. Yet it could have been good with a few changes.

Then, too, the plot thread of Rayna’s humanity could have been great. Star Trek has played with the idea of androids or computers with emotions before, but mostly it's used the concept as a plot device where such feelings can be leveraged as tools to trick or confuse hostile mechanical beings. Rayna’s awakening to human emotions could have been poignant and meaningful. Instead it felt cheap and forced. I could even have accepted her becoming infatuated with Kirk since he was one of the first humans she’d ever met besides Flint. But Captain Kirk returning her feelings is patently ridiculous, particularly given the extremely short amount of time they knew each other, her utter lack of personality, and the fact that his entire crew were hours away from painful deaths. By making the story mainly about Kirk’s feelings instead of hers, the writer really missed the mark. Two of the major problems could have been easily fixed if Kirk was focused on helping his crew while Rayna actually expressed her growing feelings for him (or for another character—either Spock or McCoy would have been a more interesting choice).

Flint watches his home-made stag film; good thing his peep show has a good cinematographer!

The interplay between Spock and McCoy was good as always, partly because Kelley is such a pro in his delivery, while Nimoy’s ‘stoic face’ is excellent. But Spock’s choice at the end killed any good will the story had managed to scrape together. The idea that Kirk, no matter what he said in a moment of weakness, would willingly submit to having his memory erased is ludicrous. Even setting aside the events of Dagger of the Mind, where he had his memory toyed with, this is a starship captain we’re talking about. I cannot believe that he would truly want a memory, even a painful one, removed. And I likewise cannot believe that Spock would do such a thing without permission. It was an interesting idea, but once again the execution fell flat because it felt all wrong. If it had been a different crewmember, McCoy for example, and if he’d given his permission, it could have been an amazing moment. Instead, it was ugly and nauseating. Quite simply, it didn’t feel like Star Trek, or at least not the Star Trek I love: where women are treated with respect, Spock would never take advantage of his captain even in the name of ‘helping’ him, and Kirk actually cares about his crew.

Two stars, because inside the bad episode there was still a good episode trying to get out.

Just Another Pretty Face

by Lorelei Marcus

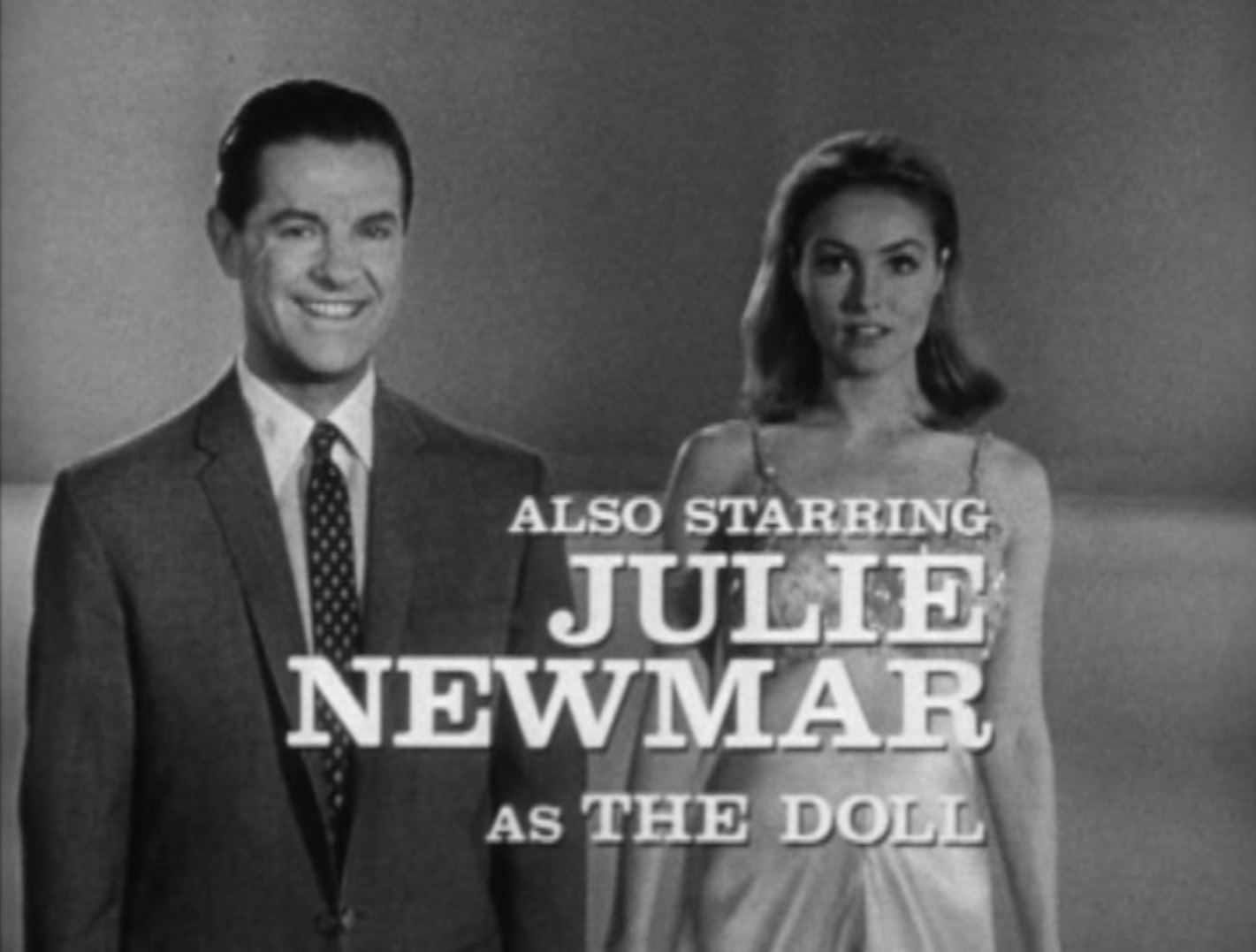

I found Louise Sorel's depiction of Rayna to be vaguely reminiscent of another blonde android I'd seen on TV a few years before: her stiff head tilts and unfocused gaze reminded me of Julie Newmar's Rhoda, the superhuman, do-it-all robot thrust into Bob Cumming's unwilling care on My Living Doll.

As Rhoda's guardian, Cummings had to ensure her artificial nature was kept secret, but this became increasingly difficult due to Rhoda's extraordinary abilities. The show shouldn't have worked, but despite Cummings' off-putting performance and his character's incompetence, it hung together—thanks to Julie Newmar's incredible physical comedy and skill. Be it the countless amusing ways Rhoda misinterpreted commands, or her incredibly mixed up piano performance, or the way she instantly slumped whenever anyone pressed the little "off button" on her back, Rhoda was a wonderfully funny character and (more importantly) individual, and she was the reason I tuned in every week to watch the show.

The same, sadly, cannot be said for Rayna. While it's true that wacky humor wouldn't suit the character nor the tone of the episode, any form of charisma would have made Rayna better than the blank slate we got. The only details we know about her are the number of degrees she has, and that she would have liked to have had a conversation with Spock—something she never actually gets to do.

Instead, she's whisked into a forced, 20-minute romance with Kirk, in which we continue to learn nothing about her personally. Then she dies, unable to make a single choice for herself because of the clashing desires of other people. Bleah.

For all that we've had too many Kirk love interests this season, I'm going to make the unpopular assertion that this one could have worked. I think Rayna could have so bewitched Kirk that he would lose sight of the urgency of saving his ship and crew, but for that to work, she would have needed to make us fall in love with her, too. Reduced to a pretty face, without initiative nor personality, I can't imagine she'd be able to seduce Ensign Chekov, much less Captain Kirk! For the missed opportunity of an interesting character, and the loss of integrity of everyone else's character as a result, I give this episode 1.5 stars.

"Train up a child in the way that he should go" — King Solomon

by Erica Frank

I planned to write about Rayna – about the utter ridiculousness of "the equivalent of 17 university degrees in sciences and art" as judged by one man. About her claim that Flint is "the greatest, kindest, wisest man in the galaxy," based on her vast experience of… an hour spent in the company of three other men.

Those made more sense after she was revealed as an android, programmed rather than taught. Others have already mentioned how bland her robotic tabula rasa personality was, without managing to be quirky or entertaining.

I find myself more interested in Flint. The man who claims to be (presumably is, in the Star Trek universe) Methuselah, Solomon, Lazarus, Alexander the Great, Merlin, Leonardo da Vinci, and Johannes Brahms. An artist, inventor, and wizard: his ultimate creation is the woman he falls in love with.

Did he invent the paper-thin large-screen television as well? Can I get one of those?

…Whom he promptly loses to a broken heart; he failed to teach her anything about how to make hard choices, how to find a solution when both options will hurt someone. …Just what did those 17 degrees cover? Any study of history should be packed with examples of art made in despair after facing choices with no good outcomes.

But why should she be facing a no-good-options choice? After six thousand years of human life, in an array of different cultures, can he not contemplate a relationship with more than two people? Solomon had 700 wives, but Flint today cannot handle the idea of a wife with two husbands?

Flint despairs that Rayna might care for someone other than him.

Ah, but Rayna doesn't see him as a husband yet—no surprise, since he's been telling her he raised her from childhood, like a parent. If she was to be his mate, why didn't he teach her that: "Someday, when you are ready, we will be married—full partners who love each other." She would've been looking forward to some unknown change, some nebulous marker of full adulthood, to take her place by his side. (With or without Kirk as a harem-boy on the side.) Instead, he treated her like a daughter, like a student, not like someone intended to be his peer.

Setting aside all of that—and much more that I didn't mention—once he had perfected Rayna, why didn't he just make another one after Kirk left? Even if he's limited to a normal human lifespan now, there's time to try again.

The current Rayna is 17. One more and she's legal!

Two stars. The idea of Methuselah changing identities and living throughout human history is fascinating, but it is bungled here.

Too Many Beaches to Walk On

by Gideon Marcus

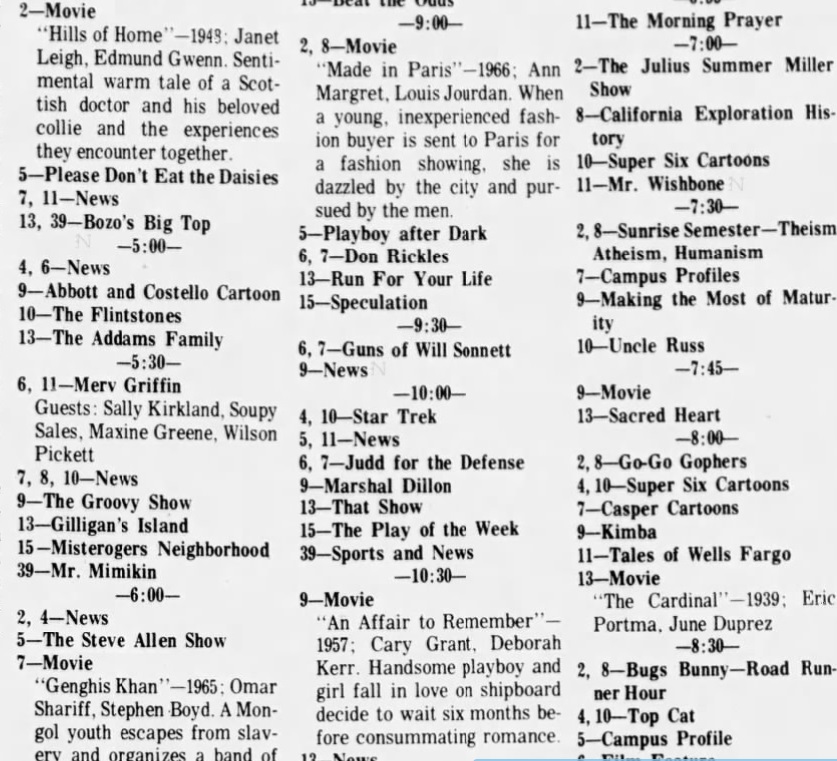

One of our readers sends us letters after every episode. He has developed a rating system not on quality, but on the number of times an element or device is used in an episode. For instance, "Wig Trek" (if there are wigs in evidence), "Cave Trek" (if there is a subterranean setting), etc.

He recently introduced a new scale: "Love Trek". More and more often, we see one member of the crew or another falling in love. This theme has been used to good effect in shows like "This Side of Paradise" (Spock falls in love, or at least, is able to express his love), "The City on the Edge of Forever" (a better case of "Tahiti Syndrome" than "The Paradise Syndrome", honestly), and "Spectre of the Gun" (Chekov and the saloon girl, whose name I can't remember.) It is less tolerable in any case involving Scotty, as the engineer, when lovelorn, becomes a moron. C'est l'amour, I guess.

It is least tolerable when it's Captain Kirk. Oh sure, the Enterprise's skipper has developed a reputation for randiness over the course of the last three years, but usually, said reputation is actually undeserved. For the most part, Kirk is the pursued rather than the pursuer, or he uses sex as a weapon, kissing antagonists until they submit. First season Kirk was positively chaste, and he recognized that his supreme obligation was to the Enterprise. Afflicted by the alcohol-like effects of the Psi 2000 disease in "The Naked Time", Kirk laments that he has no time, no capacity for love—"no beach to walk on."

It's something of a tragedy, but it's also a poignant and useful character trait. The scene in "This Side of Paradise", when Kirk's fidelity to his ship shakes the influence of the Lotus-Eater spores of Omicron Ceti Three in "This Side of Paradise", is still perhaps my favorite of the series. In "Elaan of Troyius", when Kirk is made a thrall of Elaan by her love-inducing tears, the audience knows he will break their influence once his ship is put in danger—and he does.

So howthehell does Kirk find the love of his life in less than five minutes of dancing with Rhoda Rayna the Robot? Especially such a bland, nonentity of a not-woman? (If she'd been played by Julie Newmar, there might have been some—not much, but some—justification.) Kirk's entire crew is dying. He is dying. His crew is his ship. Yet he carouses, drinks brandy, banters about Brahms and Da Vinci with Spock, and generally acts as if he is on shore leave rather than less than four hours from the death of his first and greatest love.

These three really look like they're worried about the imminent death of the Enterprise crew…

The episode is not utterly horrible. As Janice notes, there are some intriguing elements. That it has some resemblance with Forbidden Planet doesn't do it any favors, but both share an ancestry that goes back to The Tempest, so I can forgive that.

But the utter savaging of Kirk's character, not to mention Spock's uncharacteristic blasé attitude, his sudden role as a love guru, and his casual use of the Vulcan Mind Touch (remember when using such was all but tabu?) makes me hate this episode in hindsight all the more.

1.5 stars.

[Come join us tomorrow (February 21st) for the next thrilling episode of Star Trek! KGJ is broadcasting the show live with commercials and accompanied by trekzine readings at 8pm Eastern and Pacific. You won't want to miss it…]

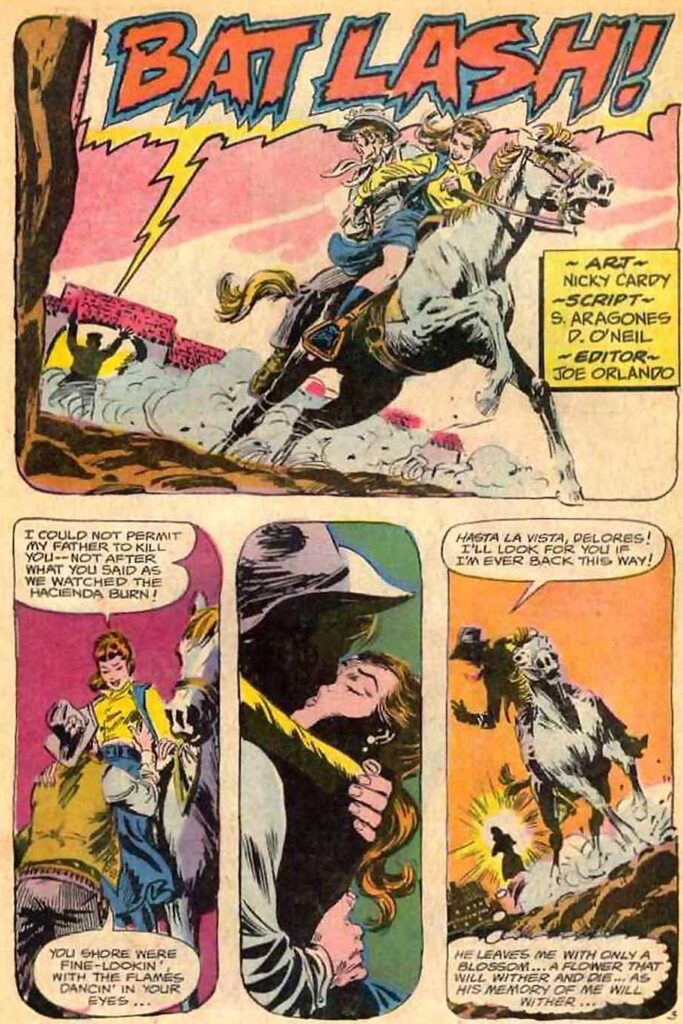

![[February 20, 1969] The Old Man and the She (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Requiem for Methuselah")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690220title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1969] (February Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690218covers-672x372.jpg)

Art by Paul Lehr

Art by Paul Lehr

![[February 16, 1969] Triumph, Tough Luck and Turmoil (European Space Update)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ESRO-1A_cover-1-672x372.jpg)

![[February 14, 1969] Like a circle in a spiral; like a wheel within a wheel (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Lights of Zetar")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690214title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1969] Slick stuff (March 1969 <i>Galaxy</i> science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690212cover-662x372.jpg)

![[February 10, 1969] Beam Me Up! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Seeds Of Death [Parts 1-3])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690210icewarrior-672x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1969] So Much for That (March 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/amz-0369-cover-492x372.png)

![[February 6, 1969] Are Comics Embracing a 1970s Mindset?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/shield9-672x372.jpg)

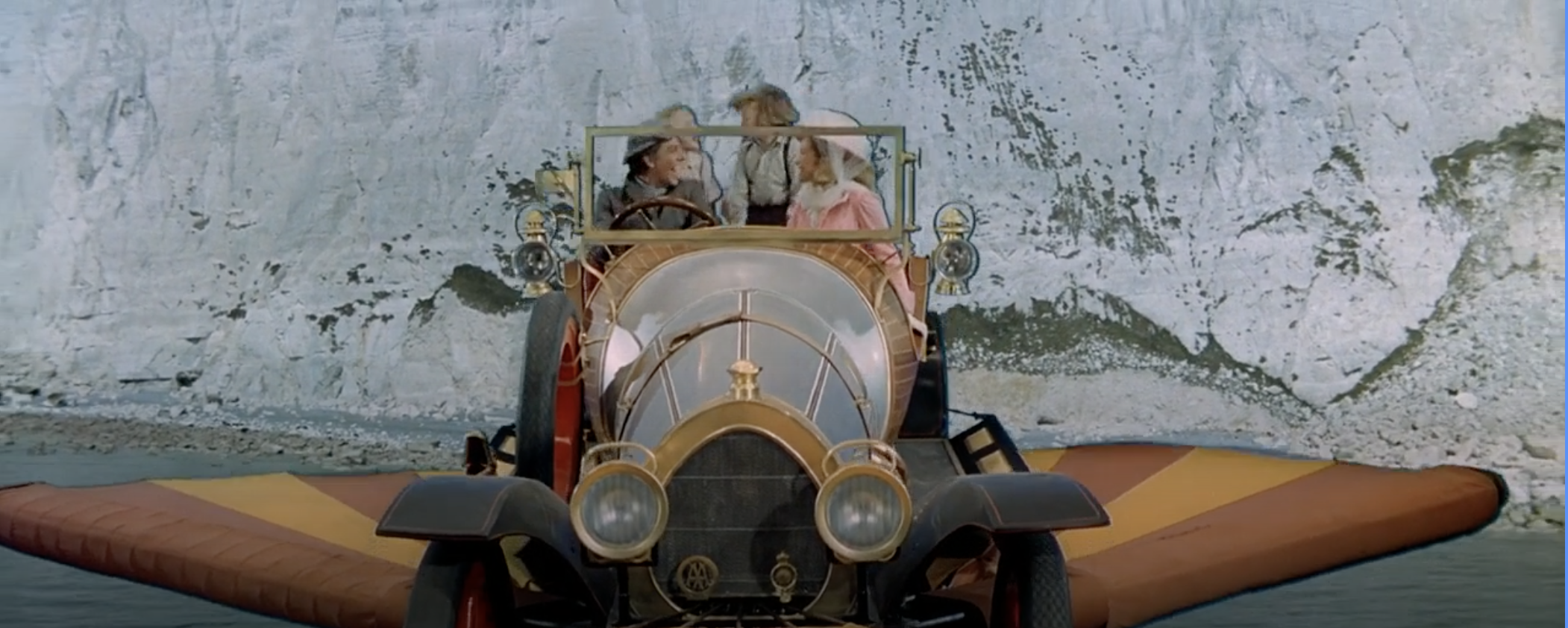

![[February 4, 1969] Potts, Caractacus Potts: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Chittychittybangbangposter-258x372.jpg)

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang takes flight

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang takes flight The Baron and Baroness profess their love for each other

The Baron and Baroness profess their love for each other

![[February 2, 1969] Winners and Losers (March 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IF-1969-03-Cover-574x372.jpg)

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on

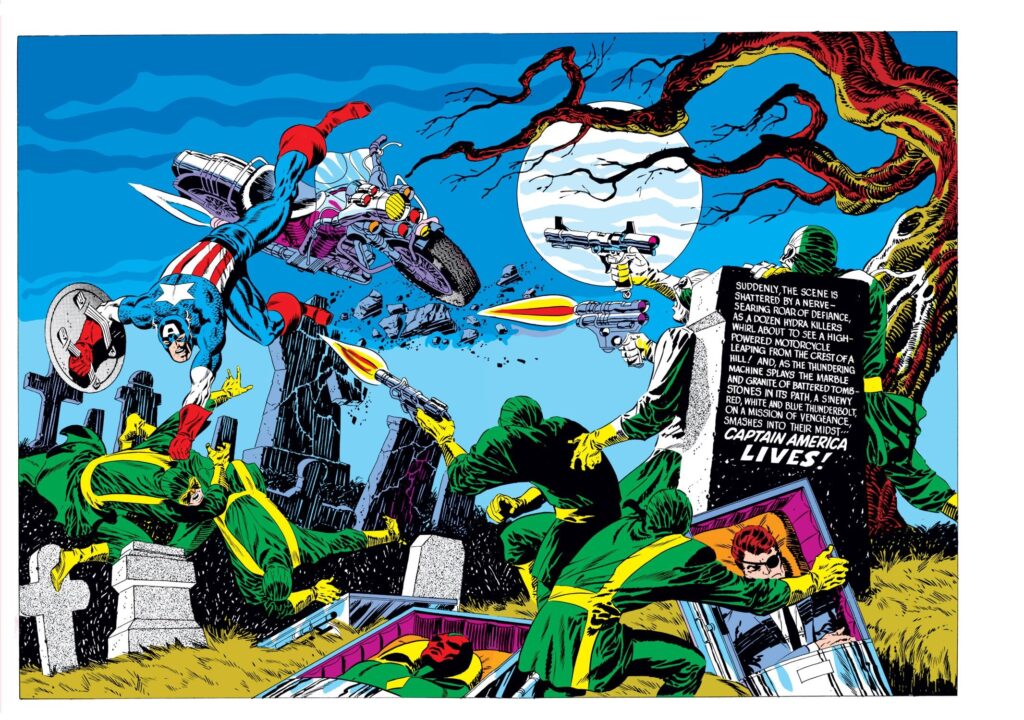

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan

The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan