by Fiona Moore

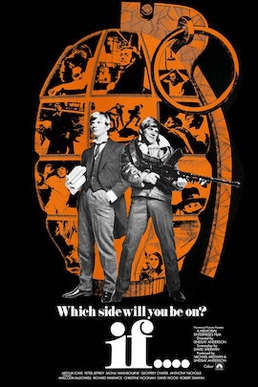

If…. is a movie which came out a couple of years ago, but is rapidly becoming a staple of the college film society scene here in the UK and overseas. It’s firmly within the satirical-surrealist tradition that characterises the likes of The Prisoner (with whom If… shares an editor, South African activist Ian Rakoff), Monty Python, and The Bed Sitting Room. The question is, how well does that stand up as time and cinematic fashion move on?

The story is set at a British all-male boarding school, where young men from the privileged classes learn the rigid, brutal, complex hierarchies and rules which will characterise their adult lives as well. Through the lens of a new arrival, we encounter a world where senior prefects enforce a rigid regime, obsessed with trivialities like hair length and permitted foods but enforcing this through corporal punishment; where younger students are forced to act as servants to their elders, with an implied sexual dimension to this servitude; where religion and the military bolster and reinforce the regime. However, the school also has its rebellious counterculture in the form of three young men, the “Crusaders”, led by Travis (played by newcomer Malcolm McDowell, whose performance here has reportedly led to Stanley Kubrick casting him in his forthcoming adaptation of A Clockwork Orange). their rebellion begins with minor acts of disobedience like growing a moustache, but grows in commitment and brutality until the climax of the story.

Continue reading [June 6, 1970] Children's Crusade: If…. (the movie, not the magazine)

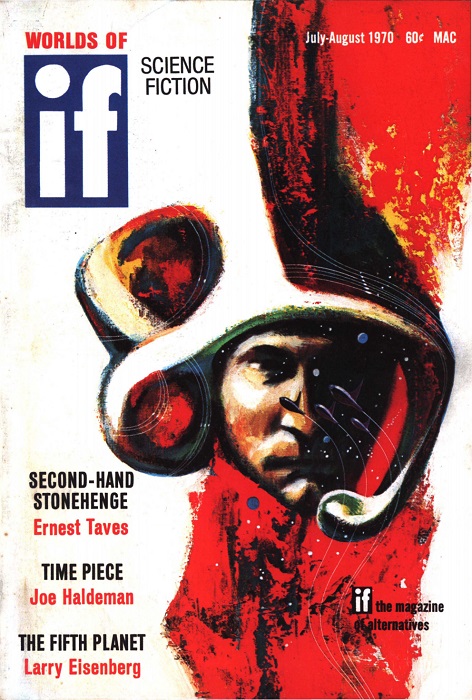

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[June 2, 1970] Turning Up The Heat (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Inferno)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700603abitundertheweather-672x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1970] A pair of Saras: <i>Flower of Doradil</i> and <i>A Promising Planet</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ace_double-672x372.png)

![[May 26, 1970] A Regrettable Case of Runaway Apophenia (Erich von Däniken's <i>Memories of the Future</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Image-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 24, 1970] Let It Be (The Beatles break up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Beatles_-_Abbey_Road.jpg)

![[May 22, 1970] Back From The Dead (Summer 1970 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1970] <i>Circus of Hells</i>, <i>Tau Zero</i>, and <i>Vector</i> (May 1970 Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700520covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 18th, 1970] Rematch (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #9</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Vis1.png)