by Gideon Marcus

Up in the Sky

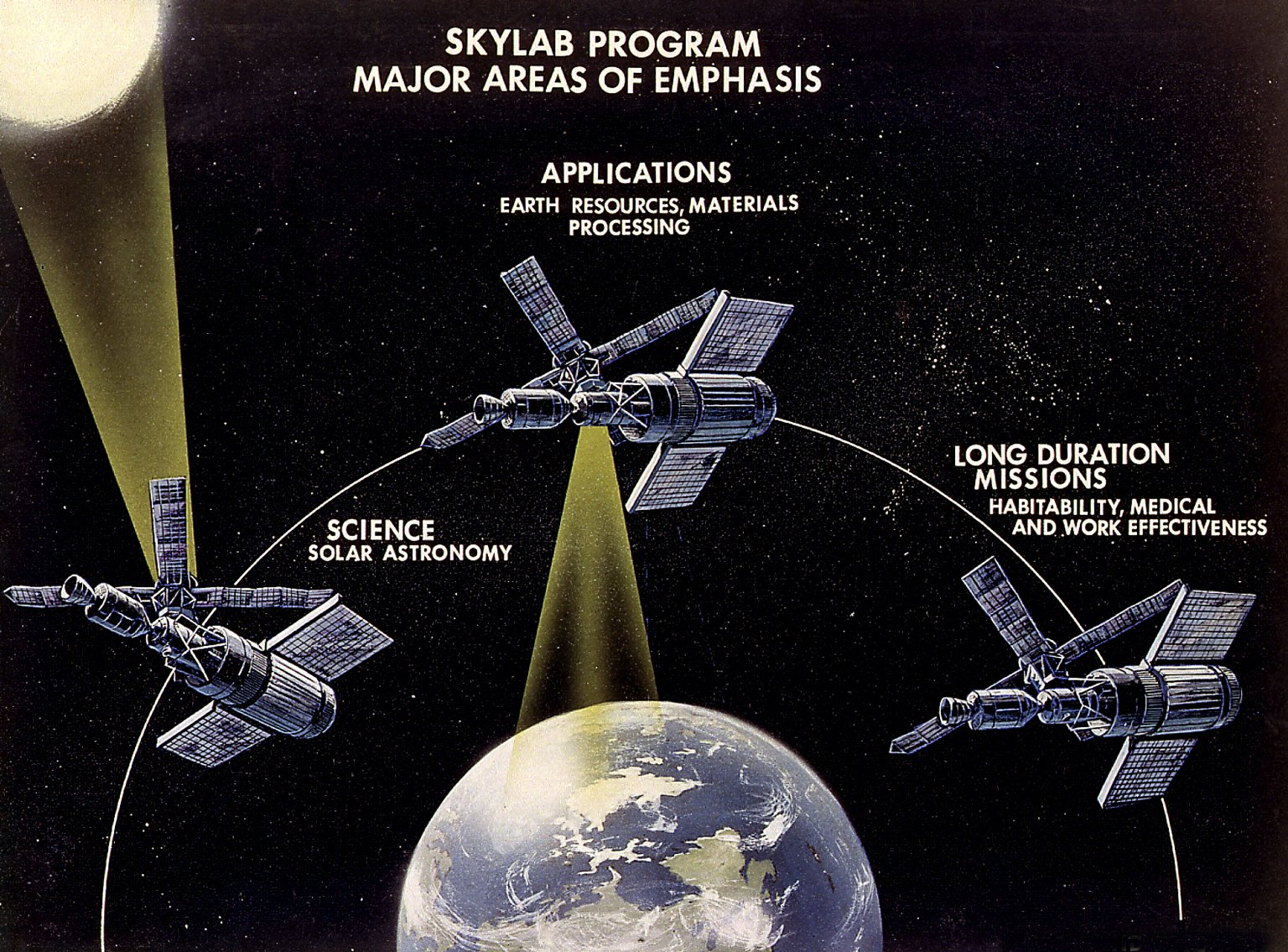

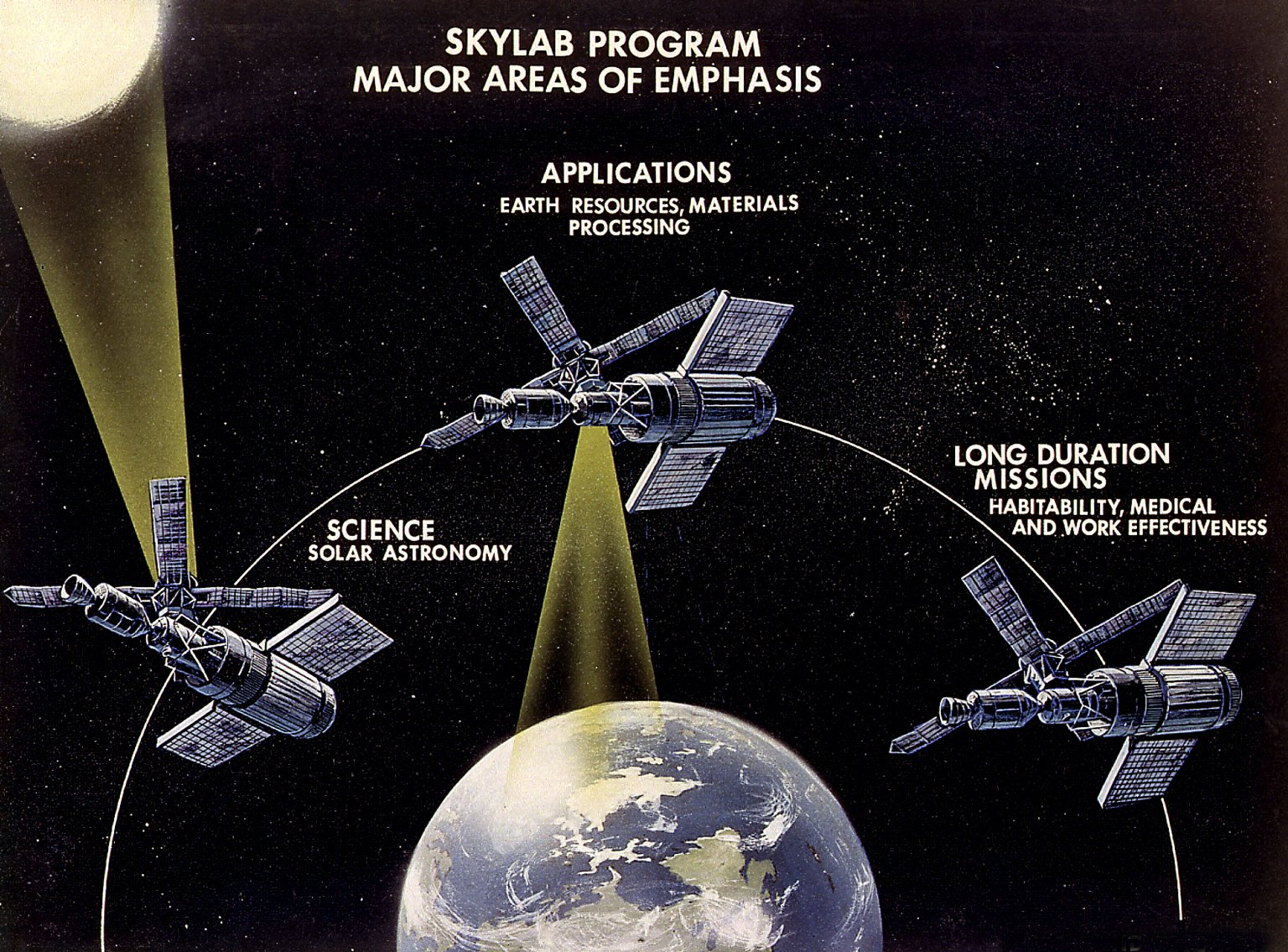

Apollo 13 may have made for great TV, but it's been terrible for NASA. This morning, in testimony before Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, NASA Administrator Dr. Thomas O. Paine reviewed the results of the Apollo 13 accident investigations and announced that the next (Apollo 14) mission had been postponed to Jan. 31, 1971–a three month delay. I imagine this is going to snarl up the meticulously planned schedule of Apollos 15-19, especially since Skylab is supposed to go up somewhere in that time frame.

…If any of these missions happen. In a recent poll of 1520 Americans, 55% said they were very worried about fate of Apollo 13 astronauts following mission abort, 24% were somewhat worried, 20% were not very worried, and 1% were not sure. More significantly, a total of 71% expected fatal accident would occur on a future mission. Perhaps its no surprise that the American public is opposed by 64% to 30% to major space funding over the next decade.

The scissor-wielders on Capitol Hill are heeding the call. Yesterday, Sen. Walter F. Mondale (D-Minn.), for himself, Sen. Clifford P. Case (R-N.J.), Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wis.), and Sen. Jacob

K. Javits (R-N.Y.), submitted an amendment to H.R. 17548 (the Fiscal Year 1971 Independent Offices and HUD appropriations bill. Not a happy one.

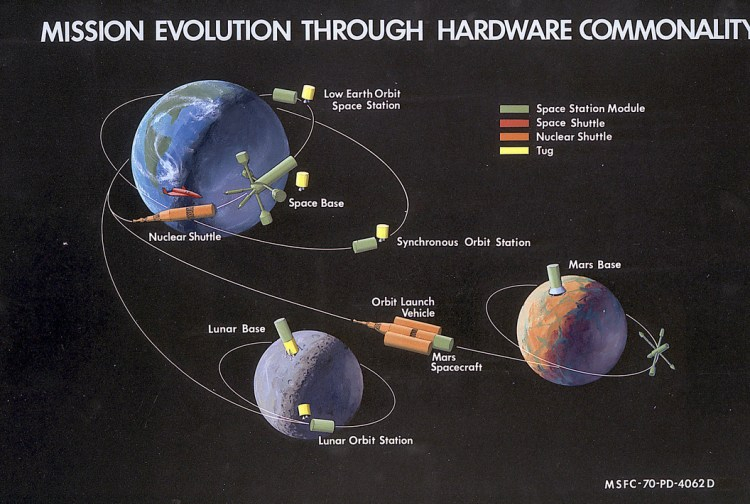

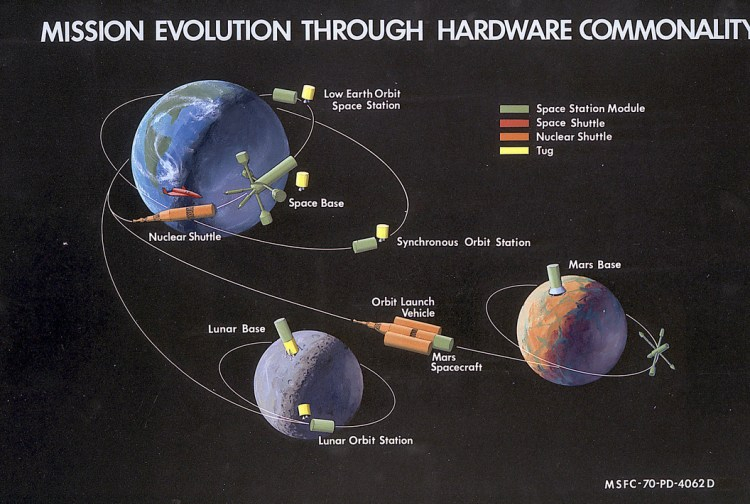

It would reduce NASA's R&D appropriation by $110 million–which just happens to be the amount requested by NASA for design and definition of space shuttle and station.

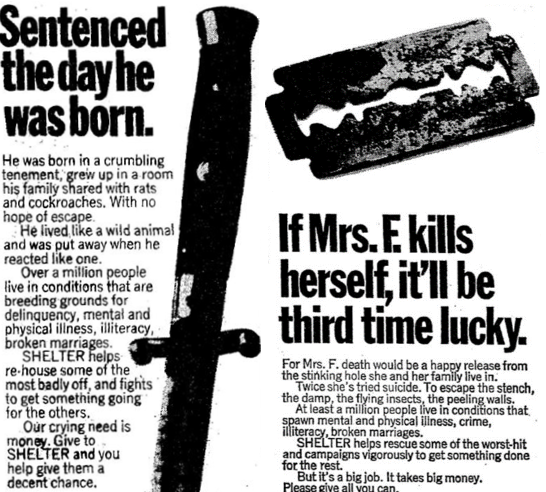

Mondale excoriated the proposal: "This project represents NASA’S next major effort in manned space flight. The $110 million. . .is only the beginning of the story. NASA’s preliminary cost estimates for development of the space shuttle/station total almost $14 billion, and the ultimate cost may run much higher. Furthermore, the shuttle and station are the first essential steps toward a manned Mars landing. . .which could cost anywhere between $50 to $100 billion. I have seen no persuasive justification for embarking upon a project of such staggering costs at a time when many of our citizens are malnourished, when our rivers and lakes are polluted, and when our cities and rural areas are decaying."

This seems a false choice to me. Surely there is such wealth in this country that we can continue the Great Society and the exploration of space, especially if we gave up fripperies like, oh I don't know, the war in Cambodia. To be fair, I know Fritz Mondale opposes the war, too, but we're talking a matter of scale here–the shuttle and station are going to cost peanuts compared to the outlay for the military-industrial complex.

That said, maybe Van Allen is right, and we shouldn't be wasting money on manned boondoggles, instead focusing on robotic science in space. On the third hand… "No Buck Rogers, no Bucks."

What do you think?

Down on the Ground

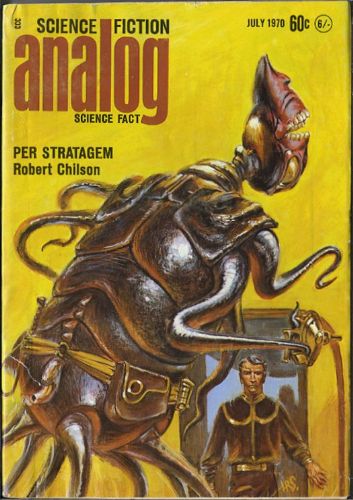

Illustration by Leo Summers

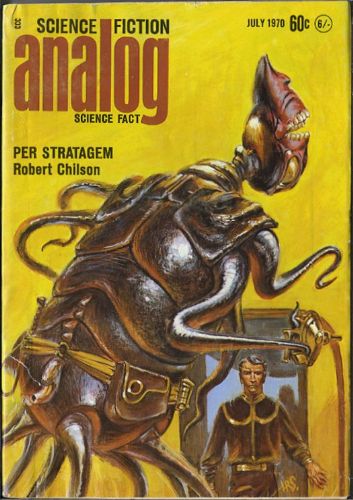

Well, if we lose our ticket to space in the 1970s, at least we'll have our dreams. Thank goodness for science fiction, and even for the July 1970 issue of Analog. Dreary as this month's mag is, it's got enough in it to keep it from being unworthy.

Continue reading [June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 Analog) →

![[July 6, 1970] The Day After Judgment (August/September 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700708galaxycover-411x372.jpg)

![[July 4, 1970] Coming Attractions (<em>The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One</em>, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Astounding_v33n05_1944-07_AK_0000-440x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Venture-1970-08-Cover-486x372.jpg)

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

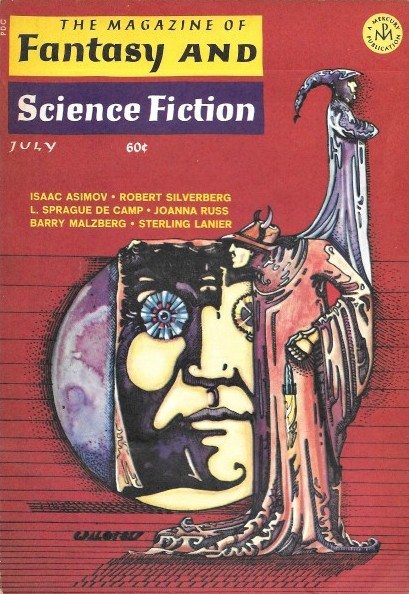

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

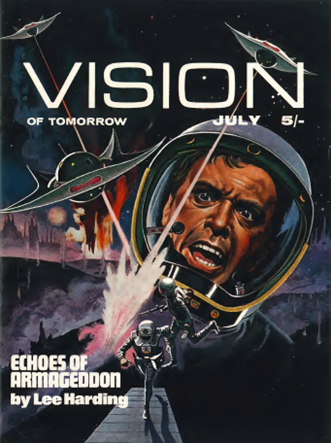

![[June 18th, 1970] A Case of Déjà Vu (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #10</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Vision-of-Tomorrow-10-Cover-331x372.png)

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

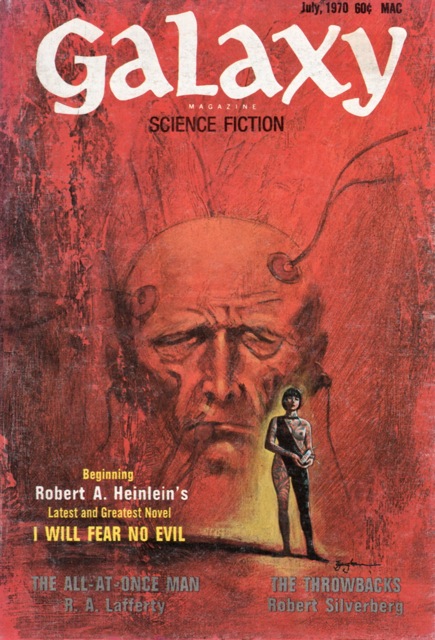

![[June 10, 1970] I will fear <i>I Will Fear No Evil</i> (July 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700610galaxycover-435x372.jpg)

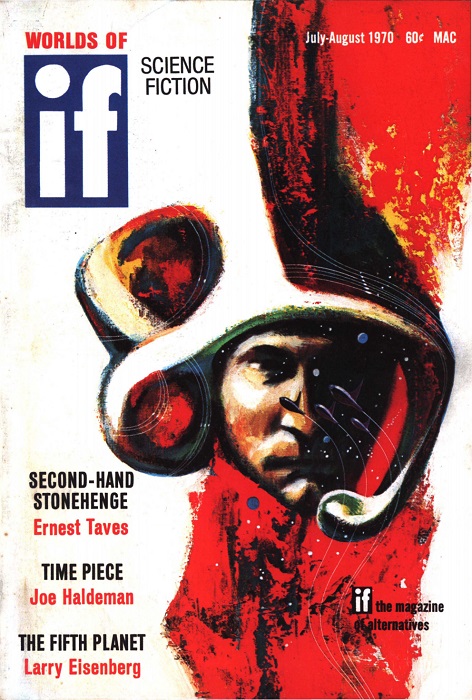

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)