Before we dive in, here's a couple of photos we just got back from the Fotomat, taken right before we watched the episode!

Captain Kirk and the Myth of Empty Land

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

This week’s episode opens with Captain Kirk and Dr. McCoy happily discussing the promise of a lush dinner for the crew of the Enterprise on the Cestus 3 colony, “out of the edge of nowhere,” after they were invited to a sumptuous visit by the local human Commodore.

When the team beams down they find destruction, death, scorched earth, and a lone and bloodied survivor. The crew takes fire from unseen enemies who Mr. Spock determines are sophisticated, cold-blooded, humanoid creatures.

Captain Kirk brings the survivor aboard the Enterprise before ordering the delightfully competent Lieutenant Sulu to follow the “alien” ship they believe is responsible for the massacre. Then follows a chase, like we saw in The Balance of Terror, during which the survivor explains to Captain Kirk that the the colony was suddenly attacked several days before, unable to defend itself.

Again and again, he asks Captain Kirk, voice rising in panic and distress: “Why did they do it? Why?”

Kirk decides the unnamed, unidentified enemy’s motivation was “invasion” and convinces Spock that the only option they have is to destroy the “alien” ship.

Eventually, a godlike species ("The Metron", yet another in a long series on this show) intervenes in the hunt, identifying the “alien” enemy ship as the "Gorn" and forcing Captain Kirk into a mano a mano fight with the alien captain on a planet where they must make their weapons off the land. Captain Kirk finds heaps of diamonds, sulfur, potassium nitrate, coal, and sturdy wood. As he freely takes of them to build a hand cannon to kill the Gorn captain, the formerly voiceless alien speaks. He explains to Captain Kirk that his ship attacked Cestus 3 because:

Gorn Captain: “You were intruding! You established an outpost in our space!”

Captain Kirk: “You butchered helpless humans –”

Gorn Captain: “We destroyed invaders!”

Observing this exchange through the magic of Metron, Spock and McCoy realize perhaps “[w]e were in the wrong” and “[t]he Gorn simply might have been trying to protect themselves.”

The makeshift gun works. Crouching over the Gorn with the alien's own chipped obsidian blade, Kirk decides to spare his life, thus surprising and delighting this week’s all powerful watcher species. Back on his ship, Captain Kirk feels proud of himself for declining to kill the Gorn captain, ending the episode with a warm smile.

The plot of "Arena" hinges on the myth of empty land, the 19th and 20th century colonialist theory that whole sections of our human world were uninhabited before Europeans arrived. Many of us descended from Europeans learned this myth in our homes and schools. Many people who lived in those lands since time immemorial learned of this myth at the muzzle of European guns.

To give a specific example, let’s consider a childhood book of my mother’s: American First: One Hundred Stories from Our Own History by Lawton B. Evans (1920). The first chapter (“Leif, The Lucky”) tells the story of Leif Erickson arriving and finding a land full of bounty, the kind of place a sensualist like Dr McCoy would enjoy: it is full of grapes and food and sturdy wood. It continues to tell the story of his brother, Thorwald, who arrives expecting a lush and welcoming land but instead, “Indians attacked his party one night, and killed Thorwald with a poisoned arrow.”

I can almost imagine Thorwald asking his crew: “Why did they do it? Why?”

Because, as the Gorn captain said, Leif and his Norsemen were the invaders. The land they came to was not empty, just as Cestus 3 was not empty. And just as Captain Kirk explained to (if he did not quite convince) his first officer, sometimes people protect themselves by cutting invaders off at the pass; in both this week’s episode and America First's first chapter, that tactic worked. At least for a time.

The stories in America First continue, from “Daniel Boone” and his handmade weapons to “Dewey At Manila Bay” and his hoards of coal. They share elements of this week’s episode: an initial erasure of indigenous people; coveting of resources; exploitation of those resources; horror at violence done to invaders (while remaining silent on violence done to those invaded); and finally, a pat ending that makes the reader feel good about his and her ancestors’ role in the story.

I read and watch science fiction to be given more than patness and comfort. I want us not only to reach for the stars, but reach into our own hearts, to give us tools to understand our complex histories, and sit with the realities of the violence that underpins many of our histories. I want to see our heroes do more than fight their way out of problems.

I am glad the episode takes a stab at addressing the "empty land" myth, and at the same time disappointed that its hero does not. In the end, Captain Kirk seems to have some realization of the Gorn captain’s perspective, but the episode ended before we saw any true change of heart. I want to see real attempts at understanding the “alien” perspective for longer than the time it takes to put down a knife.

Three stars.

A Weak Echo

by Erica Frank

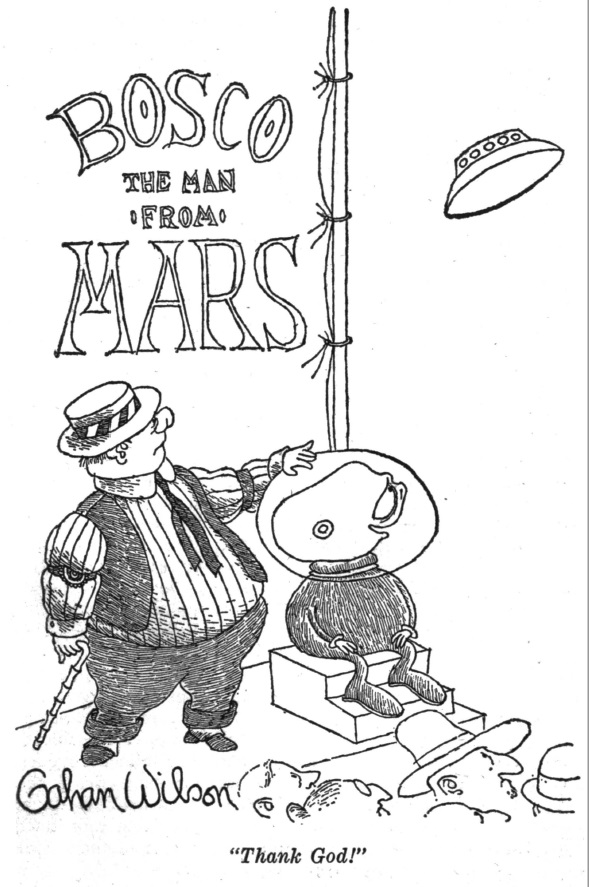

This episode was obviously inspired by Frederick Brown’s 1944 story, “Arena.” In both stories, aliens have attacked human settlements and space battles follow. In both, a near-omnipotent being interferes, reducing the conflicts to a single contest: One representative of each, placed on a barren world, instructed to fight. The godlike entity will then remove the loser’s contingent.

The two stories have some crucial differences, however.

Most importantly: In the original, the human is naked. (The alien probably is, but it looks like a giant red beach ball.) In the Star Trek episode, Kirk is not only not naked, his shirt doesn’t even get torn. (Despite fighting an alien with fangs and claws! Did the budget department object to constantly replacing his uniforms?)

In the original, the stakes were much larger: The nameless cosmic entity will eliminate the loser’s entire species; in Trek, “the Metron” only says he will destroy the loser’s ship. (He seems annoyed that they’ve brought their petty squabble to his region of space.) Brown’s “Arena” mentioned prior battles, skirmishes leading toward a full-scale war. In Trek, this is the first time they’ve met, which makes Kirk’s instant hostility seem arbitrary and contrived.

Just last week, Kirk insisted they were peaceful explorers, not warriors. Now he’s jumped to “alien invaders seeking conquest—kill them all” without considering any other options. He chases the alien ship, ignoring Spock’s requests for diplomacy, pushing the Enterprise nearly to breaking… until the Metron stops both ships and places both captains in their arena.

Brown’s human protagonist—Carson—and his alien are separated by an invisible force field, unable to attack each other directly. Their battle involves wits and endurance, not brute strength. Kirk throws rocks.

Unlike Kirk, Carson attempts to negotiate peace with his enemy; it “replies” with a mental wave of hatred and bloodlust. Unlike the Gorn, there will be no diplomatic relations in the future. Instead, Carson must find a way to kill his enemy—with the entire human race as the stakes of the battle.

I won’t ruin the story for you, but the result is predictable. The question is not “who wins,” but “how?” In this, it is again much like the Star Trek episode: We do not wonder whether Kirk (and his ship) will be destroyed, but how they will prevail.

The original is much more satisfying than the Trek episode. Carson’s explorations and growing understanding of his situation make sense; Kirk has more resources but ignores technological options (including fire) until his rocks fail to kill.

However, this episode of Trek was not without points of interest: the Gorn was an intriguing alien, and the Metrons use their immense powers to enforce peace in their area; they don’t treat “less advanced” species like toys for their amusement. I hope to see both of them again.

Three stars, even though Kirk remained fully clothed throughout.

Will the real civilization please stand up.

by Andrea Castaneda

This episode exemplifies what happens when a good idea isn’t executed well. I appreciated how this "Arena" explored the idea of barbarism vs civilization. But the way the storyline unfolded left me with some conflicting messages.

Throughout the episode, we’re presented with three different tiers of civilized society: the allegedly barbaric Gorns, the more rational Humans, and highly advanced Metrons.

When the Gorns are introduced, they're framed as violent aliens who attacked Cestus III unprovoked and showed no mercy. Then we have the humans of the Starship Enterprise, who we can identify as the more rational species. But as Captain Kirk's desire for vengeance shows, we can be prone to our own bloodthirsty tendencies. Then we have the Metrons, a species so advanced, they command the laws of physics at will. And while they claim to be the epitome of what a truly civilized world looks like, they still deemed a trial by combat the best course of action rather than, say, a civil trial (even Trelane offered a trial!) But then again, had they chosen that option, we'd have been robbed the spectacle of Bill Shatner fighting a man in a rubber lizard suit.

I was particularly struck when, after much rock throwing, a brief chemistry lesson, and lots of underwhelming stunt choreography, Kirk finally defeats his opponent. The impressed Metron suddenly shows up (dressed as if a cherub from a renaissance painting appeared on the cover of Vogue) to commend Kirk on his display of mercy, yet in the same breath offers to destroy the Gorns anyway!

At this point, I wondered whether the Metrons were really as advanced as they claimed. After all, by declaring the crews of both ships guilty by association, they could have potentially killed many innocent lives. At least with Captain Kirk, who had much more emotional investment in the outcome, he realized when to hold back.

I suppose the moral this episode left me with is that no society, no matter how advanced, is immune to the perils of barbarism.

Three stars.

Fight or Flight

by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

I have to say that I’m really enjoying Star Trek so far. “Arena” isn’t the best episode for reasons that others have already expressed, but the last few episodes of Star Trek have left me with questions of what the Enterprise’s goals are in seeking out new life and civilizations.

We’ve seen that Kirk takes exploration seriously in “The Galileo Seven”. He stops to explore a quasar while transporting lifesaving medicine to a waypoint for a colony in need. He’s battled and bluffed his way through confrontations in space and has also shown prowess in hand-to-hand combat, but are humans exploring the galaxy just to get into fights? It’s understandable that conflicts are sometimes unavoidable, but at times, it seems as though Kirk is just looking for a reason to arm his photon torpedoes. I’m not saying that it’s unheard of for explorers to be capable of defending themselves, but it does seem a bit odd that Kirk’s approach to alien life tends to be confrontational and aggressive.

Kirk goes boldly where no man has gone before, but when does bold become brash? Seeking out new life seems dishonest when it often results in unnecessary conflict. He’s almost immediately opposed to General Trelane’s behavior in “The Squire of Gothos” and now, without asking any questions, he immediately chases after a fleeing ship with the intent to destroy it. To be fair, they did destroy a colony full of seemingly innocent people, but if Enterprise’s role is mainly to explore the galaxy, it’s not clear based on Kirk’s actions. At no point did the Enterprise's captain even try to communicate with the Gorn. Initiative was left to the other party, who reached out to him, explained his viewpoint, even offered his version of mercy.

I think Kirk just got lucky in the end. It made no sense for him to spare the Gorn and there was little indication that he should. What bothers me is that it’s yet another arbitrary standard enforced by a supposedly morally superior alien. Kirk’s mettle was subjectively assessed to be passable using a lousy test that was barely passable in its own right. This would have been a more interesting episode if Kirk’s mercy was rewarded with peace between humans and Gorn rather than a heavy-handed pat on the head by an almighty alien. Good boy, Kirk. You’ve shown mercy. If only there was another way a superior alien could coax a human into showing mercy than a gladiatorial contest.

3 Stars

Ineffective effects

by Janice L. Newman

Thus far, Star Trek has proven itself a cut above just about all other science fiction shows currently playing in the USA. The stories are often sophisticated, the alien menaces sympathetic, there are questions of morality and nuanced plotlines that you simply do not get in, say, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. The special effects, too, are often innovative and surprisingly convincing. The ship made of lights in "The Corbomite Maneuver" stands out, but even effects used across multiple episodes like the glitter of the transporter or the beam of a phaser just work, never jarring the viewer out of the story with how fake they seem. The salt monster in "The Man Trap", despite being the quintessential ‘man in a suit’, managed to be scary rather than ridiculous, and the bulbous-headed alien in "The Corbomite Maneuver" looked fake because, in a brilliant twist, it was.

"Arena" proved to be a disappointment in this, well, arena.

The first half of the episode is interesting. The ‘warzone’ that Captain Kirk and several of his crew find themselves in works well enough, using explosions combined with clever light effects similar to those used for the phasers. However, when Kirk is sent to confront the ‘Gorn’, we encounter one of the first special effects that threw me out of the story entirely.

The Gorn is a man in a suit. It’s a very good suit: well-designed and detailed. It’s clearly meant to be intimidating, with lots of teeth, faceted eyes, and big muscles. Unfortunately, it’s painfully obvious that the poor person inside the suit can barely move. The Gorn is slow, lumbering, and stiff. I can handwave some of this away. Maybe the Gorn’s planet has different gravity, or properties that give its particular bodily development an evolutionary advantage. Yet when Kirk fights the Gorn almost in slow-motion, giving time for the Gorn to swing back, I couldn’t help but immediately be reminded of every cheesy children’s sci-fi show and every low-budget sci-fi movie where a man in a suit tries to be convincingly scary.

They did their best. Kirk uses his speed to his advantage, darting around the rocks while the Gorn plods after him, convinced its superior strength will win in the end. It should be compelling, but as much as I wanted to, I couldn’t engage with it. I just couldn’t see the Gorn as anything but a man-in-a-suit.

There’s also the point that a supposedly advanced race that ostensibly values mercy and peace set up this “Arena” with the components of gunpowder and other tools available such that the two leaders can brutally kill each other, with the lives of their respective crews hanging in the balance. But others have already made that point.

Three stars.

Nothing if not consistent

by Gideon Marcus

I'm going to be the contrary one today. Everyone else, for various reasons, has given "Arena" some flavor of three stars. I'm going to give it a lot more.

Jessica makes a valid point. The episode neatly brings up the "empty land" myth. But unlike Jessica, I feel the showrunners did their job. Indeed, they did it twice. For it is not just Gorn land that was trespassed, but that of the Metrons. If the Gorns (and by extension, the Skraelings of Vinland) are justified, then surely the Metrons are also justified in whatever actions they want to take to rid their space of the noisome invaders. That their morals don't necessarily match ours is not surprising; "advanced" is a loaded term. Kirk and the Gorn were the equivalent of two roly-polies unwanted in a garden. The Metrons simply put the two of them in a little dish to see what would happen.

Personally, I don't believe the Metrons ever intended to kill anyone (or let anyone die), similar to Balok in "The Corbomite Maneuver". They were just having fun and teaching us a lesson at the same time: Don't barge into unknown space without knocking.

As for Kirk being a lousy diplomat, point conceded. But his actions are nothing if not consistent. In "Balance of Terror", he dithered over engaging the Romulans despite a crystal clear course of action. In "Arena" he is determined not to make that same mistake again even though, as Mr. Spock points out, the circumstances are not necessarily the same.

And Mr. Spock, what a gem you are. In "The Galileo Seven", he consistently finds solutions that result in the least loss of intelligent life, regardless of species. Here he tries repeatedly to do so again, to the point that he is curtly silenced on the bridge by the captain.

We are frequently given to believe that Kirk is a brilliant commanding officer, someone to be admired. But more and more, Star Trek is showing us who we really should root for. Not the headstrong captain who is starting to favor his guns to his communicator, certainly not the overemotional McCoy, who seems to exist only to tease Spock about being an alien. No, it is the cool, rational (if not always "logical" in the way Jessica would define the term!) Mr. Spock. And maybe Mr. Sulu. He was pretty nifty this episode, too.

And Uhura. That officer's got some good pipes on her.

Four and a half stars.

It looks like the Enterprise is going to meet Major Nelson this week!

Come join us tonight at 8:30 PM (Eastern and Pacific). Here's the invitation!

![[July 4, 1970] Coming Attractions (<em>The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One</em>, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Astounding_v33n05_1944-07_AK_0000-440x372.jpg)

![[January 26, 1967] Cold-blooded murder (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Arena")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670126title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1966] Past? Imperfect. Future? Tense. (March 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fantastic_v15n04_1966-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

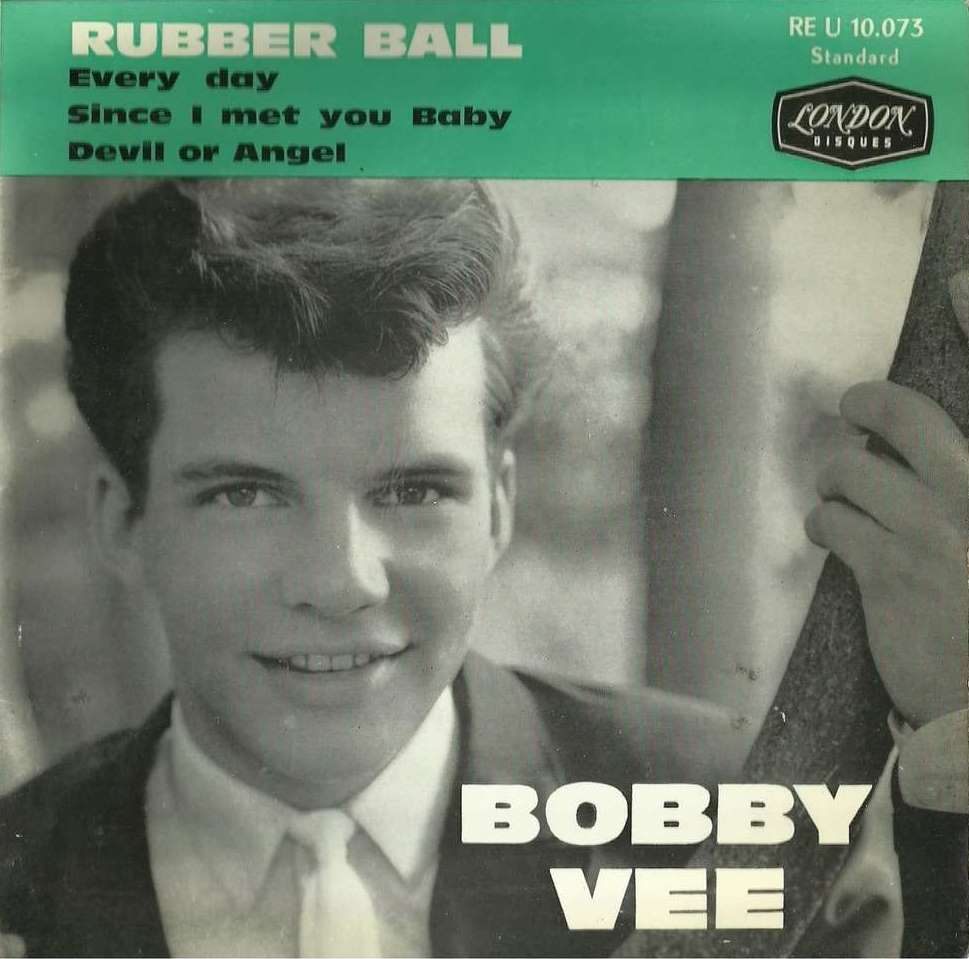

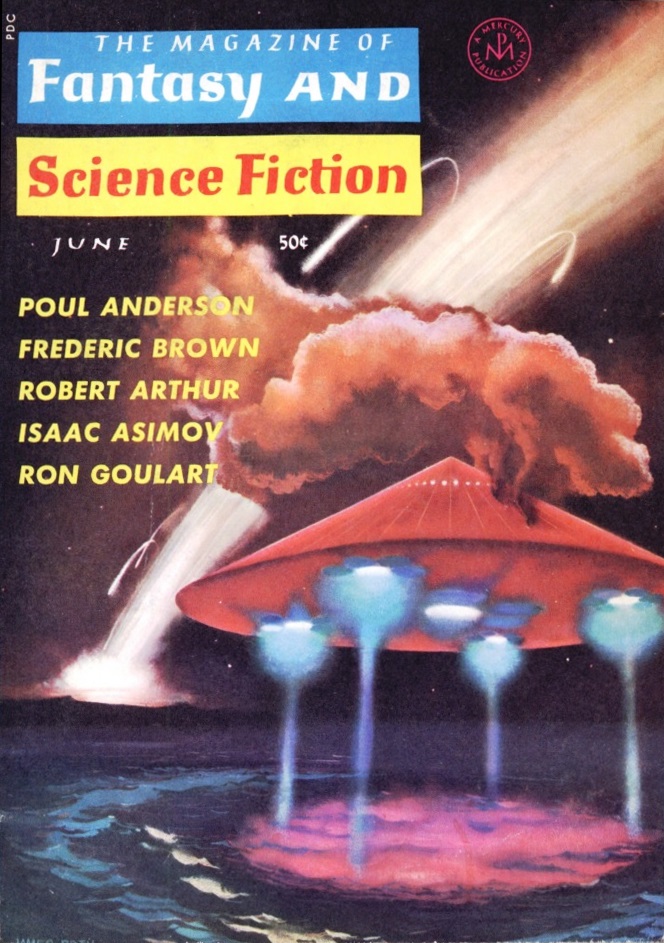

![[May 18, 1965] Rubber Ball (or Skip the End) (June 1965 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650518cover-664x372.jpg)