by John Boston

Suspicions confirmed—this November Amazing names as Editor Barry N. Malzberg, who was listed last issue as Associate Editor. Sol Cohen is now merely the Publisher. Oddly, though, the editorial is by Harry Harrison, now listed as Associate Editor (though most likely gone). Go figure, or just say it’s more Sol Cohen chaos.

Johnny Bruck is back as the cover artist; this one (from Perry Rhodan #109, published in 1963) looks even more cliched and perfunctory than his earlier covers, making me wonder if they are really getting worse, or if I am just getting more tired of them.

by Johnny Bruck

“New” is sprinkled across the cover wherever possible to distract from the fact that once again, reprints dominate. Four new short stories take up 36 pages, just under 25% of the magazine. And the prize: “plus stories by: RAY BRADBURY (Winner of the Aviation Space Writers Association’s Top Award). . . .” Does Bradbury need that kind of boosting?

One of the new stories, interestingly, is a collaboration between Harlan Ellison and Samuel R. Delany. When Delany appeared with a novel excerpt in the issue before last, his name was misspelled about half the time; this issue, it’s misspelled “Delaney” everywhere—on the cover, on the contents page (twice), on the first page of the story, in the book review column. Well, small mercy, it’s spelled right in the blurb for the story.

There are worse production botches, discussed when I get to them.

Harrison’s editorial, Science Fiction and the Establishment, is superficial and banal: the Establishment doesn’t like SF, it’s a problem all over, but it’s starting to get better, someday it will be gone. The book review column continues interestingly but incestuously, with James Blish as William Atheling reviewing Larry Niven, and Samuel R. Delany reviewing Blish. Leon E. Stover contributes another in his “Science of Man” series, discussed below.

Despite all the above kvetching about the magazine’s presentation, the good news is that the new short stories are as interesting a batch as we’ve seen in Amazing for a while, and the reprints are all readable or better, unlike many of their predecessors.

Power of the Nail, by Harlan Ellison and Samuel R. Delany

Ellison and Delany’s Power of the Nail reads like what Ellison was publishing in the SF magazines around 1957, polished up by a smoother writer. Robert Zagaramendo and his wife Margret are Ecological Observers on the planet Saquetta, and boy howdy is Margret pissed: “You promised me better than this, somewhere.” Robert’s not too thrilled either, especially with Margret. Bickering is constant.

Saquetta features the Saquettes, mole-like aliens who are not at all cute, but have the interesting trait of being reincarnated when they die naturally, which is most of the time. But the vibrations of the “phase-antenna of the automatic ecology equipment” that the humans are burying in various locations draw the Saquettes away from their usual hideouts to places where they are vulnerable to attack by giant predatory birds, called molloks because that’s what the Saquettes scream when they’re being hunted.

by Dan Adkins

After further conflict with his wife, including a near-rape, Robert sets up “ecology equipment” near an especially large Saquette colony, complete with lurking molloks, and goes back later to find, as expected, hundreds of dead Saquettes. He builds little round coffins for them and nails them together, then goes back and tells Margret that they’re going home—and shortly, suffers a terrible and fatal punishment that is not clearly explained, though one may surmise it is related to the operation of the "automatic ecology equipment." (Compare David H. Keller's The Doorbell if you've ever read it.) In the moral universe of the story, it’s obviously because he decided to sacrifice hundreds of Saquettes in order to escape an emotionally intolerable situation.

It's a very vivid and readable story, which goes some way towards compensating for its ultimate obscurity. Three stars.

The Monsters, by David R. Bunch

The formerly prolific David R. Bunch, who has not appeared in Amazing since Sol Cohen took over, is back with The Monsters. It’s short as usual for Bunch, and on a familiar theme: the need to harden one’s small children against the brutalities of life by brutalizing them pre-emptively. (See Bunch’s earlier story A Small Miracle of Fishhooks and Straight Pins, Fantastic June 1961, and thence to Judith Merril’s annual “year’s best” volume.) Here, the threat the children are to be prepared for is a bit trite, but the writing is brisk and economical. Three stars.

Try Again, by Jack Wodhams

Jack Wodhams is new to me, though the Journeyer-in-Chief has not thought highly of his work in Analog. His Try Again is surprisingly good. Pyler, a psychiatrist, is having a session with the precocious five-year-old Tommy, who says he has lived before and remembers it. But this isn’t quite the same life as before, since with adult memories he acts differently the second time around. Tommy is much burdened by his knowledge of future events and the question whether he could do anything about them (it’s 1935, Mussolini has just invaded Ethiopia; and Tommy knows what comes later). Shortly he is kidnapped to Germany. An alternative history, even worse than the real one, is telegraphically unfolded. Tommy, who has disappeared from the plot after his interrogation, reappears at the terrible end. Four stars—maybe a bit crude, but powerful.

by Jeff Jones

The reading experience is undermined at the end by Amazing’s production values, or lack of them. The story stops on page 29 in the midst of a sentence with no “continued on” notice, and the reader is left to rummage through the magazine to find the rest of the text on page 138.

This Grand Carcass, by R.A. Lafferty

R.A. Lafferty’s This Grand Carcass is, typically, told in high Tall Tale mode, and it is also clearly a moral tale, though the precise moral may be a bit obscure. Mord comes to Juniper Tell offering to sell a device cheap that will allow Tell to “own the worlds.” So why is he selling it? He’s dying. Tell bites and is the new owner of Gahn, for Generalized Agenda Harmonizer Nucleus, which soon enough is outdoing and dominating all the other “general purpose machines.” Shortly, it is a full partner with Tell (in Tell and Gahn—get it?).

Before long, Tell, like Mord, is almost, er, gone, and Gahn (whose power inputs have been revealed as dummies) candidly admits: “I use you. I use human fuel. I establish symbiosis with you. I suck you out. I eat you up.” So Tell sells Gahn on to the next high-rolling sucker. Moral, did I say? Machines are the Devil? Anything that makes humans’ work too easy is damnation? Something along those lines, I’m sure. This is not one of Lafferty’s best; it is simultaneously obvious and vague and less deliciously absurd than Lafferty at his best. But it’s amusing enough, good for three stars.

The Dwarf, by Ray Bradbury

In Ray Bradbury’s The Dwarf (Fantastic, January/February 1954), Mr. Bigelow, a dwarf, visits the carnival daily, forks over his dime at the Mirror Maze, and heads straight for the mirror that makes him look large. Aimee, a carnival worker, hangs out in the booth with ticket-seller Ralph when her business is slow. She is sympathetic to Mr. Bigelow’s plight. Ralph isn’t, and makes fun of him, and of her. Aimee discovers that Mr. Bigelow makes a living writing detective stories, which reveal his inner torments. Ralph plays a nasty trick on him, proving that Ralph is nasty, which we already knew.

by Sanford Kossln

Rather abruptly, end of story. Or is it? There’s no “Continued on . . .” at the end. As with Try Again, I rummaged through the magazine, but found no loose piece of the story. So I checked the original 1954 Fantastic . . . and there’s an entire page of text at the end that is omitted from this reprinted version.

No rating, since the full text doesn’t actually appear in the magazine. It’s not one of Bradbury’s better stories to my taste, but it’s a whole lot better complete than truncated. Sheesh.

The Traveling Crag, by Theodore Sturgeon

The Traveling Crag, from the July 1951 Fantastic Adventures, is a silly confection by Theodore Sturgeon—a non-trivial category of his ouevre. On the other hand, silliness by Sturgeon is more palatable than that from less accomplished hands.

Cris is a literary agent with an assistant, Naome, who is obviously in love with him, though he is oblivious. Cris has received a story, The Traveling Crag, from an unknown, Sig Weiss, which “grabs you by the throat, shakes your bones, puts a heartbeat into your lymph ducts and finally slams you down, gasping, weak, and oh so happy,” and incidentally makes a lot of money fast. But Weiss sends no more stories. Cris visits to find out why, and the local storekeeper warns him, “Meanest bastard ever lived,” a judgment Weiss lives up to in the flesh.

by Lawrence (L. Sterne Stevens)

When Weiss finally submits another story at Cris’s urging, it begins: “Jets blasting, Bat Durston came screeching down through the atmosphere of Bbllzznaj, a tiny planet seven billion light-years from Sol.” This is the beginning of a notorious subscription ad that ran in Galaxy, headlined YOU’LL NEVER SEE IT IN GALAXY!, designed to distinguish Galaxy’s policy from that of lowbrow pulp magazines like . . . Fantastic Adventures and Amazing Stories. So to perpetrate this in-joke, Sturgeon must have convinced not only Galaxy editor H.L. Gold, but also Fantastic Adventures editor Howard Browne, to allow it.

But I digress. The point is that Weiss has turned in a bunch of crap, continuing his mean-bastard performance. Meanwhile, Cris meets Miss Tillie Moroney, who is offering a reward for an “authentic case of devil into saint,” and eventually tells him a story—“a science fiction plot”—about a humanoid race that has developed the ultimate weapon, one of which has apparently been lost on Earth for thousands of years. And she wants Cris to get Weiss to write another blockbuster story and then find out how and where he wrote it.

So Weiss produces another story that makes everyone cry, and Cris and Tillie head out to see him, but Naome the assistant contrives to get there first, and the ultimate weapon, a small object found after a rockslide, proves to have been the key to Weiss’s transformation, but it gets triggered, and one of Tillie’s blouse buttons emits communications from the humanoids, who explain to them all telepathically that the ultimate weapon was one that stops useless conflict, and now a reaction is propagating through the atmosphere to bring the weapon’s benefits to all the world (it’s science!), and by the way Naome has paired off with Weiss, and Nick with Tillie. “Outside, it was a greener world, and all over it the birds sang.”

It's all just Too Much, but rendered so smoothly as to disarm even the house misanthrope’s ire. Three stars for this feat of making fatuity charming.

He Who Shrank, by Henry Hasse

“Years, centuries, aeons, have fled past me in endless parade, leaving me unscathed, for I am deathless, and in all the universe alone of my kind. Universe? Strange how that convenient word leaps instantly to my mind from force of old habit. Universe? The merest expression of a puny idea in the minds of whose who cannot possibly conceive whereof they speak. The word is a mockery. Yet how glibly men utter it! How little do they realize the artificiality of the word!”

Yes! Rave on! Here is a fine specimen of the peak of cosmos-spanning rhetoric occasionally reached by early (pre-Campbell) SF, and what follows lives up to it in naïve grandeur. It is the first paragraph of He Who Shrank, by Henry Hasse, a novella from the August 1936 Amazing.

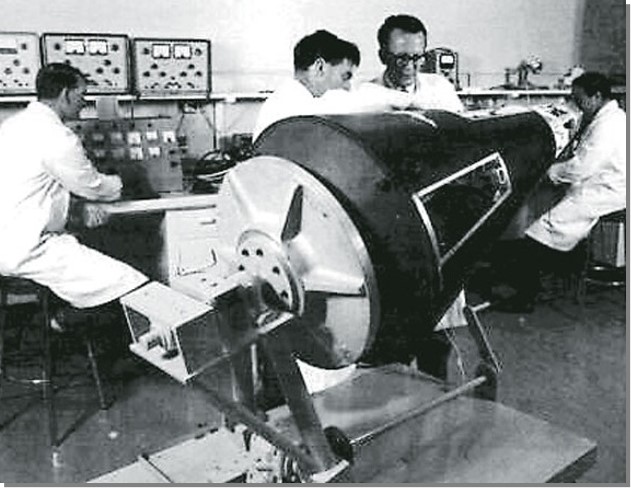

The plot is essentially that of The Man from the Atom run backwards. Atoms are solar systems and galaxies are molecules, and the Professor has devised a substance (called Shrinx!) that will reduce humans to subatomic dimensions so they can explore the sub-universes. When his unnamed assistant is unenthusiastic about making this one-way trip, the Prof stabs hin with the needle. As he shrinks, the Prof drops him onto a block of Rehyllium-X (sic!), where he descends into a microscopic scratch on its surface and is chased around by a germ, fearsomely portrayed by illustrator Morey.

by Leo Morey

Soon enough, our hero finds himself surrounded by luminous masses—nebulae!—and then, as he shrinks further, stars and planets. He alights on one occupied by gaseous intelligences, shrinks further to a planet of cave-dwellers, and then (in a powerful passage) to a planet of machines gone out of control. Their birdlike creators have fled to the world’s moon, as their mechanical heirs maniacally tear down the remains of their civilization and remake the world closer to their circuits’ desire.

Our hero continues downward, or smallward, through universes he cannot bring himself to recount except in the most summary form (“Suns dying . . . planets cold and dark and airless . . . last vestiges of once proud races struggling for a few more years of sustenance . . . [etc.]”) But then . . . he is mysteriously attracted to a tiny, distant spark of yellow, which on approach proves to be circled by planets including a tiny blue one that twinkles invitingly, so he approaches, descends, and finds himself in . . . Cleveland!

Well, actually, he lands in Lake Erie, flooding much of Cleveland as well as nearby Toledo. Upon attaining dry land, he is accosted by aircraft shooting at him, which he finds annoying. He is bundled into a vehicle and taken to Cleveland, to a building where scientists assemble to interrogate him, but are unable to understand his thoughts, though he can read theirs. He is not impressed by them, or humanity. He escapes and flees into the countryside, where he is drawn to an isolated house occupied by a writer, of science fiction of course, who is sufficiently enlightened to be capable of receiving his thought, and to whom the shrinking man tells his tale before continuing his apparently endless and by now wearisome voyage.

In one sense this is an odd story for Amazing to reprint, since it appeared in the 1946 anthology Adventures and Time and Space, edited by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas—one of the oldest stories in the book, and the only one from Amazing. That book is so well known that stories included in it are much more likely to be familiar to current Amazing readers than most of Sol Cohen’s other reprints. I read that anthology when I was a kid and wondered what this old-fashioned story based on scientific nonsense was doing in the company of Heinlein, Asimov, et al. But I’m younger than that now and can better appreciate its hokey majesty. Four stars, allowing for its age.

Henry Hasse (b. 1913) began publishing SF in 1933; this is his third published story. Aside from it, he is best known for collaborating with Ray Bradbury on a few minor early stories. None of his other work, which has appeared sporadically over the decades, has garnered the recognition that this story has.

One side note: This story presents a very early occurrence of what later was named Tuckerization, after its heavy use by Wilson Tucker: giving fictional characters the names of real members of the SF community. The Cleveland writer to whom the shrinking man tells his story is named Stanton Cobb Lentz, obviously a reference to Stanton A. Coblentz, a prolific SF writer mainly of the late ‘20s and ‘30s, whose work is nowadays most charitably described as quaint.

The Last Day, by Richard Matheson

by Robert Kay

In Richard Matheson’s The Last Day (Amazing, April/May 1953), the Sun is about to destroy Earth (it’s swollen and red and much too hot). Protagonist wakes up after the last night, which he and friends have spent in drunken, lustful, and/or senselessly destructive pursuits. He decides this approach to the end is unsatisfactory, and after wrestling with his conscience reluctantly heads to his parents’ house (shooting an attacker en route). He has avoided this visit for years because of his mother’s excessive piety. But on this final hot day, she’s cool, and they hang out waiting for the end. The editor blurbs: “Waxing philosophical is like waxing a floor; it is powerful easy to fall on your face while trying it.” Matheson does not. Four stars, mainly for keeping just on the right side of bathos as he renders the conventional sentiments.

Science of Man: War Is Peace, by Leon E. Stover

Leon E. Stover is back with another of his “Science of Man” articles, War Is Peace, written in his usual dogmatic style. He takes on the likes of Konrad Lorenz (of On Aggression), arguing that aggression is not a mode of behavior that we must sublimate or otherwise redirect, but a goal-directed extension of human social organization. He says: “The ethologists have nothing to offer that can improve on what Karl von Clauswitz said of war in the 19th century: that it is an extension of politics carried on by different means.” And he concludes: “There is no magic solution to be found in animal behavior studies, psychology, or biology. Do not be misled. The only solution is better politics. But we have to know that to want it.” Well, maybe—he has no suggestions for how we get there in practice. But Stover recounts much entertaining anthropological lore along the way.

Three stars.

Summing Up

Well, that wasn’t bad at all. The new material is lively and interesting, and even the reprints are all readable or better, with nothing grossly stupid or incompetent. Admittedly, that shouldn’t be the standard, but in Sol Cohen-world it does make a difference. This issue is a magazine that one might actually purchase for enjoyment and not as a duty, a change not to be sneezed at. Can it continue?

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[April 4, 1969] Hey, Mack! (April 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690331cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[November 30, 1968] Up, Up, and Around! (December 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681130cover.jpg?resize=575%2C372)

![[October 28, 1968] Impressive at first glance… (November 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681028cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[October 6, 1968] Snail on the Slope? (November 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/amz-1168-cover.png?resize=245%2C347)

![[September 16, 1968] Siriusly? (October 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680910cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[July 31, 1968] No easy answers (August 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680731cover-scaled.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[March 28, 1968] Design for effect (April 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680328cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[January 31, 1968] Too much and too little (February 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680131cover.jpg?resize=651%2C372)

![[December 4, 1967] Devaluation (<i>New Writings in SF-11</i> & <i>Beyond Infinity</i> December 1967)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Cover-Image.jpg?resize=672%2C372)

![[November 30, 1967] One door closes… (December 1967 <i>Analog</i> and Australia joins the Space Race!)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671130cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372)