by Gideon Marcus

Summertime, and the living ain't easy

Our longest, hottest summer began early with the shooting of Bobby Kennedy. It heated up to the sound of Soviet bullets and tank treads in Czechoslovakia and reached a crescendo with the fiasco of a Democratic Convention in Chicago, shuddering in synchronicity with the quake in eastern Iran that killed 10,000. Meanwhile, radioactive rain from the French H-bomb test soaks Japan, Pete Seeger's daughter, Mika, has been in a Mexico City jail for two months (for participating in anti-police protests), and the 82 crew of the U.S.S. Pueblo are still locked up in North Korea (for participating in unauthorized offshore fishing exercises).

But, hey, thanks to the war in Vietnam, unemployment is at its lowest rate since Korea. And America has a new Queen, Miss Judith Ford, formerly Queen of Illinois.

Her "subjects" demonstrated a properly American sentiment toward the coronation. Spurred by a collective called the New York Radical Women, several hundred protesters tossed "beauty" accoutrements into the "freedom trash can": bras, girdles, high-heeled shoes, fake eyelashes, etc. So there was a bright spot, of sorts.

I wouldn't sent a knight out on a dog like this…

I apologize for coming off sour. It's not just the season. I've got a humdinger of a virus, and the latest issue of Galaxy is only making me feel worse.

by Douglas Chaffee

The Villains from Vega IV, by E. J. Gold and H. L. Gold

by Jack Gaughan

Fred Pohl, editor for Galaxy, likes to talk about how Gold, the founding editor for the magazine, was legendarily zealous with his red pen. Not a single story made it through the slush pile (or any other) without looking like it had been through a Prussian duel. Now, one could argue that there was merit to this approach: much of vintage Galaxy is superlative.

However, when Gold first submitted a story for an anthology Pohl was putting together, Fred could not help taking delight in a bit of revenge. He contrived to mark everything, even innocuous conjunctions and prepositions. When it was done, there was more red than black and white. The dedication this must have taken!

Reportedly, Gold called Pohl up, and said something to the effect of, "Fred, you're the editor, and I'll defer to your judgment, of course, but…Jesus!"

In any event, it couldn't be this story to which Fred was referring since Villains was co-written by both Gold and his son, Eugene (but not, as I initially thought from the initials, his wife, Evelyn). It's the silly story of Robert E. Li, President of Vega IV, who comes to Earth to find his young bride, who has run off to be in pictures. Andytec, a diffident young android, is dispatched to accompany him as bodyguard and detective.

There are some interesting concepts, like the Vegan tradition of 36 year olds marrying 18 year olds, who themselves find new partners upon reaching 36. At 54, one is then free to marry whomever one likes. And there's the Bird of Perdition, a chimerical creature biologically rooted into the heads of former criminals (including, surprisingly, the Vegan President). Semi-intelligent, they spout Poe-derivative prose when alarmed.

But all in all, the story is not funny enough, nor does it break enough ground (indeed, it feels vaguely like a washed out A Specter is Haunting Texas) to sustain its novelet length. One good bit, however:

"Turn that bloody thing off!" he shouted at me.

"Off, sir?" I said vacantly. "You can change channels and make it louder, but you can't turn it off. With the 3V off, what would there be to do? And it would be so lonely."

Two stars.

All the Myriad Ways, by Larry Niven

by Joe Wehrle, Jr.

Things look up a bit, as they always do, with Niven's latest. An L.A. cop is trying to decode the recent rash of murders and suicides, all spontaneous, few logically motivated. The timing suggests a connection with Crosstime, the company that just began producing vehicles that can transit parallel time tracks. In addition to bringing back marvels from other histories—worlds where the Confederacy won the Civil War, or where the planet has been bombed into searing radioactivity—it has also discovered a philosophical crisis. If everything that could ever be does exist somewhen, does anything you do really matter?

And would you kill/die to find out?

As usual, the value of the tale is in Niven's crisp telling. I particularly liked the revelation that the world our detective inhabits is not our Earth. There's not quite enough to the story to make it truly memorable. It's more of an idea-piece (or, per the author, an anti-idea piece; he doesn't buy the idea of parallel universes, nor does he appreciate their implications. This is the ad absurdum extension of the concept.)

Of course, I think there is a middle ground: probabilities do exist. Just because there are two options doesn't mean their chance of occurring is 50/50. Or as I tell folks, if I flip a coin, it's 50% likely it comes up heads or tails. But it's 100% likely the coin falls down rather than up.

So while there may be an infinity of universes, it would seem they would all remain confined to the possible, and the preponderance tend toward the probable. I could also see timelines sort of merging back together if they were close enough.

Anyway, a good story, and thought-provoking. Four stars.

Thyre Planet, by Kris Neville

by Dan Adkins

One day, an alien race called the Thyres all, suddenly, disappeared. They left behind an inhabitable world and a working, planetary teleportation booth grid. Of course, humans jumped at the chance to settle the planet.

The hitch: each use of the booth has an infinitesimal but non-zero chance of killing the traveler. Hundreds die each year. A Terran scientist is dispatched to solve the problem. Convinced it is tied to some abstruse physical law, he secures billions in funding to crash-start a Manhattan Project to rewrite cosmic law. The endeavor takes on a life of its own, ultimately eclipsing the original problem. Said problem remains unresolved until the end, and it turns out to be caused by something completely different.

I found this a deeply frustrating story. Is it a satire of scientific institutions? A cautionary tale advising us to look for simple explanations before complex ones? A screed against hasty colonization? it all muddles together without a satisfactory payoff. Maybe I read it wrong.

Two stars.

Homespinner, by Jack Wodhams

by Joe Wehrle, Jr.

Boy, this was a hard one to rate. It's about a fellow who lives in a future where houses can be done up in a day, rooms completely redecorated as quickly as one might, today, swap out a picture on the wall. Said fellow is annoyed that his wife keeps changing his home on a weekly basis. All he wants is some consistency in his life. Indeed, you can't help wondering why the couple are together at all, so incompatible they seem. The husband also seems awfully sexist, expecting his wife to stay at home and do virtually nothing but greet him cheerfully after work.

Of course, you'll figure out what's up with their relationship before it's revealed, and that bit is reasonably clever. The problem is, the getting there is repetitive and unpleasant. I get why, but I feel a more skilled author could have put it together better.

For some reason, however, I appreciate it enough to give it three stars.

Criminal in Utopia, by Mack Reynolds

by Brand

In yet another story exploring "People's Capitalism", the American welfare state of the 1980s, a citizen embarks on a crime spree to improve his lot. After all, in a system where everyone is supposed to be equal, the only way to get ahead is to cheat.

The question is: in an economy where income is strictly tied to each person, and all transactions are electronicized and trackable, can a person get more than he deserves?

As usual for Reynolds, a mildly diverting story and some very interesting technologies. Three stars.

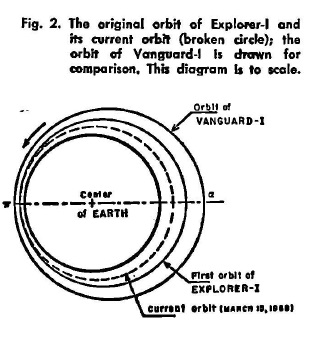

For Your Information: The Orbit of Explorer-1, by Willy Ley

Despite the sexy subject matter (I dig space stuff), this piece on…well…the orbit of Explorer-1…is pretty dull stuff. I think Ley's heart just isn't in these articles very often anymore.

Three stars.

I Bring You Hands, by Colin Kapp

by Virgil Finlay

A rather amoral fellow is a Hands merchant. These are tape-programmable, robotic hands that can do a physical task an infinite number of times. Perfect for replacing assembly line workers, tailors, cooks, you name it. Along the way, the salesman has an affair with one of the workers whose job he causes to be roboticized. The end is not a pleasant one for the Hands dealer.

I had a lot of hopes for this story. I thought it was going to make some sort of statement about mechanization, the ensuing unemployment, and how society adapts to change. Instead, it was all thrown away for a cheap, obvious, macabre finish.

Two stars.

A Visit to Cleveland General, by Sydney J. Van Scyoc

by Jack Gaughan

Two brothers were in an air-car accident. Just one emerged. So why does Albin have trouble distinguishing himself from the deceased Deon? Why does he need to take a pill every morning "for memory"? And what are those aerosols Miss Kling, the nurse at Cleveland General, keeps spraying to affect everyone's mood and recollection? Particularly in surgery, where body parts are shuffled into various people, muddling the identifies of donor and recipient?

Visit is a decent enough piece, thematically and literally, though you'll guess what's going on very quickly. Scientifically, it makes no lick of sense.

Three stars.

The Warbots, by Larry S. Todd

by Todd

You'd think I would be quite keen on a fictional history of legged assault vehicles. This one, however, is both too goofy and far too long to scratch that itch.

Two stars.

Behind the Sandrat Hoax, by Christopher Anvil

by Safrani

My first thought upon reaching this final piece was, "Oh, great—a Chris Anvil epistolary story."

And that thought was justified.

It's about how a prospector on New Venus discovers that eating the raw stomach of a desert rat allows the consumer to digest water from grass, but the proud scientific community doesn't like the way the research is done and impedes progress. All of the scientists are made of straw, you see.

I was surprised not to find this in Analog—I guess sometimes things are too lousy even for Campbell. On the other hand, Campbell gets the credit for tainting Anvil so that he's now worthless wherever he publishes.

One star.

Dimmer than a thousand squibs

2.4 stars. Not only is that dismal, but recall that an issue of Galaxy is half-again as long as a normal mag.

There's a reason I paused for breath halfway to tear through The Weathermonger (and that is a good read!) Anyway, all things pass, and summer's only got five days left to it. Surely next season will see an improvement, yes?

![[September 16, 1968] Siriusly? (October 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/680910cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1968] Froth and Frippery (July 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680610cover-653x372.jpg)