Our last two Journey shows were a gas! You can watch the kinescope reruns here).

You don't want to miss the next episode of The Journey Show, April 25 (tomorrow) at 1PM PDT featuring professional flautist Acacia Weber as the special musical guest serving up some groovy period tunes.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Can't Anybody Here Play This Game?

Sports history was made this month, with the first major league baseball game played indoors. It took place inside the newly completed Harris County Domed Stadium, located in Houston, Texas. The exhibition game between the Houston Astros and the New York Yankees took place before nearly fifty thousand fans, including the President of the United States. Fortunately for LBJ and other native sons of the Lone Star State, the home team won, two to one, after an exciting game lasting twelve innings.

There's something futuristic about a baseball diamond under a dome, isn't there?

So what's the fly in this athletic ointment? Well, the game was played at night, which disguised a serious flaw in the design of the stadium. During daylight hours, if the sun isn't blocked by clouds, the transparent panels covering the dome cause a lot of glare. Fielders can't see fly balls, leading to a whole bunch of errors. Oops.

Is This Music Or Comedy?

In yet another invasion of the American music charts by a British band, a bunch of fellows calling themselves Freddie and the Dreamers reached Number One with a cheerful, if undistinguished, pop song called I'm Telling You Now.

If you think they look a little silly here, wait until you see their act.

This superficial ditty would quickly fade from the memory of anybody listening to it on AM radio, or on a 45, I think. However, if you happen to catch the Dreamers performing live or on TV, I doubt if you'll forget the antics of Freddie, doing a bizarre dance that looks like something they made you do in PE class. The combination of the sound of the Beatles and the look of Jerry Lewis is disconcerting, to say the least.

Situation Normal; All Fouled Up

Given these missteps in the worlds of sports and music, it seems appropriate that many of the stories in the latest issue of Fantastic features situations that go from bad to worse. One of the paradoxes of literature is that misfortune can often make for enjoyable fiction. That's not always true, of course, so let's take a look and judge each effort on its merits.

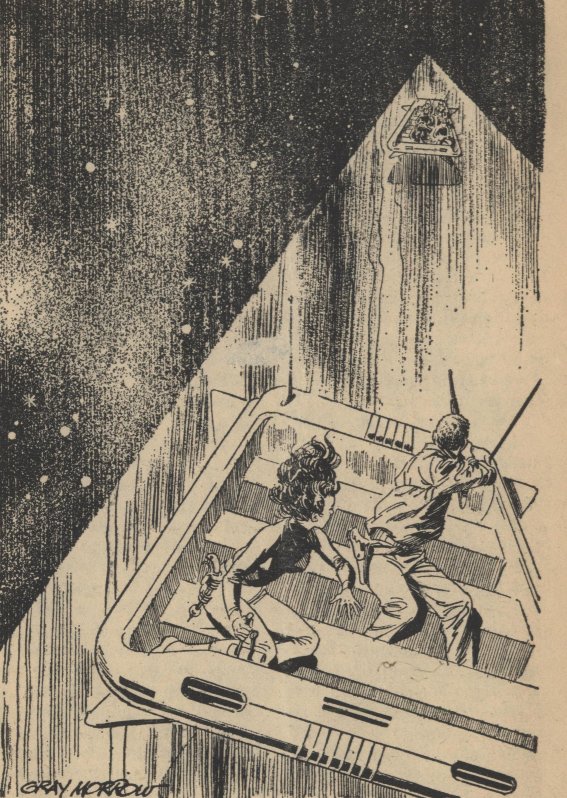

Cover art by Gray Morrow. I hope you like it, because there are no interior illustrations at all.

The Crib of Hell, by Arthur Pendragan

Speaking of foul-ups, the magazine starts off right away with a mistake. It's obvious that the last name of the creator of this gruesome horror story should be Pendragon, not Pendragan. How do I know? Well, for one thing, that version of the name appeared with a very similar tale in the April 1964 issue. For another, anyone familiar with the myths of Camelot knows that Pendragon is the correct spelling of King Arthur's surname. I don't know who's hiding behind this royal pseudonym, but he or she has more in common with H. P Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe than the Once and Future King.

New England, 1924. In the suggestively named town of Sabbathday, a doctor visits the mentally tortured inhabitant of an isolated mansion. (His role should be played by Vincent Price.) Since the death of his spinster sister, he's been charged with (dramatic pause) the Guardianship. It seems that his late father's second wife, named Ligea (an apparent allusion to Poe's short story Ligeia — another change in spelling!) was a witch. Just before her death, she gave birth to a deformed creature, kept locked up in the mansion. Ghastly events follow.

There aren't many surprises in this chiller. The reader is ready for the monster to appear long before it steps onto the stage. After a slow start, the action builds to a frenzied climax. The resemblance to a horror movie that I've hinted at above grows stronger at the ambiguous last scene, when there should be one of those The End (?) final credits that you get at the conclusion of some scare flicks.

Three stars.

Playmate, by David R. Bunch

We return to the dystopian world of Moderan, where things have gone badly many times before. In this disturbing future of endless automated warfare and people who have replaced most of their bodies with metal, a little girl receives a robot playmate. Her barely human father has other uses for it.

There's not really much plot to this grim little tale, other than the basic premise. The author's unique style, and what seems to be a sardonic look at the thin line between humans and machines, make up for this lack, to some extent.

Three stars.

The Other Side of Time (Part Two of Three), by Keith Laumer

It would be tedious for me to try to provide an accurate summary of the dizzying array of events that occurred in the first third of this novel. (Besides, I'm lazy.) Suffice to say that the narrator, after a ton of wild adventures in multiple alternate realities, is now in exile in yet another world, with much of his memory erased.

This is a place where Napoleon was triumphant, so the planet is dominated by the French Empire. Technology is at the level of steam engines and the early use of electricity, without the gizmo that allows folks to journey between different realities. Even though the narrator manages to regain his memory, with the help of a hypnotist who disguises herself as an old crone, it seems impossible for him to return to his home.

Or is it? In a desperate attempt to recreate the device he needs, the narrator and the hypnotist, now a loyal companion, travel to Rome, in search of this world's version of the scientist who invented it. After much effort, some of it on the comic side, he succeeds.

Or does he? It's out of the frying pan and into the fire, because now he's in a prehistoric world, full of dangerous beasts. Only the very end of this installment offers a hint as to how the narrator is going to get out of this mess.

After the breakneck pace of the first segment, this portion comes as something of a relief. A touch of comedy, when the narrator uses his wits rather his fists to get what he wants, is most welcome. The hypnotist is a very appealing character. She's intelligent, capable, and brave. There's a hint of romance between the two, but since the narrator is happily married in his own world, I assume this isn't going to continue. In any case, I liked this third a little better than the first one.

Four stars.

Terminal, by Ron Goulart

A writer better known for slapstick farce offers a much darker vision of the future than usual. A man finds himself in a home for the elderly run by robots. He's not old, so he knows he doesn't belong there, but parts of his memory are gone (just like in the Laumer.) The inefficient robots aren't any help at all, and things go very badly indeed.

Much of the story deals with the fellow's interactions with the other inhabitants of this hellish institution. These characters are sketched quickly, in effective and poignant ways. I was particularly taken with the man who just quotes poetry at random. The whole thing is a powerful, bitter satire of society's treatment of the elderly.

Four stars.

Miranda, by John Jakes

The time is the American Civil War. The place is Georgia, during Sherman's March to the Sea. A Union officer loses the rest of his outfit. Knocked unconscious when he falls from his horse, he wakes up in the plantation home of a woman whose husband was killed by the Yankees. She holds him prisoner, taunting him with the point of a saber and offering him poisoned wine. The officer sees strange, frightening apparitions, and learns the terrifying truth about the woman.

This is a fairly effective ghost story, with a convincing portrayal of the time and place. The author shows a gift for historical fiction, and he may not need supernatural elements to succeed in that genre.

Three stars.

Red Carpet Treatment, by Robert Lipsyte

There's not a lot to say about this two-page oddity. Passengers on an airplane hear an announcement that they're on their way to Heaven. The folks aboard the plane — a priest, a child and his mother, a young married couple, a rich man and his girlfriend, and so on — react in various ways. There's a slight, predictable twist at the end.

I suppose it's about the way we deal with the awareness of death. I'm not sure if it's supposed to be a joke or not.

Two stars.

Junkman, by Harold Stevens

Things are also going very wrong in this story, but this time the intent is strictly humorous. A series of brief vignettes throughout time show stuff getting all mixed up. There's a bowling ball in prehistoric times, a typewriter in the Dark Ages, etc. Eventually we figure out that a super-genius invented a time machine, and caused all the chaos. Since this is a time travel story, we've got a paradox at the end. I found it overlong and not very amusing.

One star.

I Think They Love Me, by Walter F. Moudy

At first, this seems to be a war story, as we witness a scarred veteran, too old for active service at the advanced age of twenty-four, lecture young recruits on the dangers they face. Pretty soon we figure out that these guys are the members of a rock 'n' roll band, and that the enemy consists of hordes of screaming teenage girls. As in just about every other story in this issue, things don't work out well.

I like this mordant satire of Beatlemania more than it deserves, maybe. Sure, the premise is silly, and mocking teen idols isn't the most original thing in the world. Yet somehow I found its mad logic compelling enough to go along with it.

Three stars.

Light At The End Of The Tunnel?

After reading about all these fictional mishaps and disasters, it may be tempting to be a little fatalistic about the state of fantastic fiction these days. On the other hand, although this issue has a couple of losers, there's also some decent reading to be had. I suppose it all depends on how you look at it.

A recent ad for what may be one of the late JFK's most important legacies.

![[April 24, 1965] Every Silver Lining Has A Cloud (May 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Fantastic_v14n05_1965-05_0000-2-672x340.jpg)

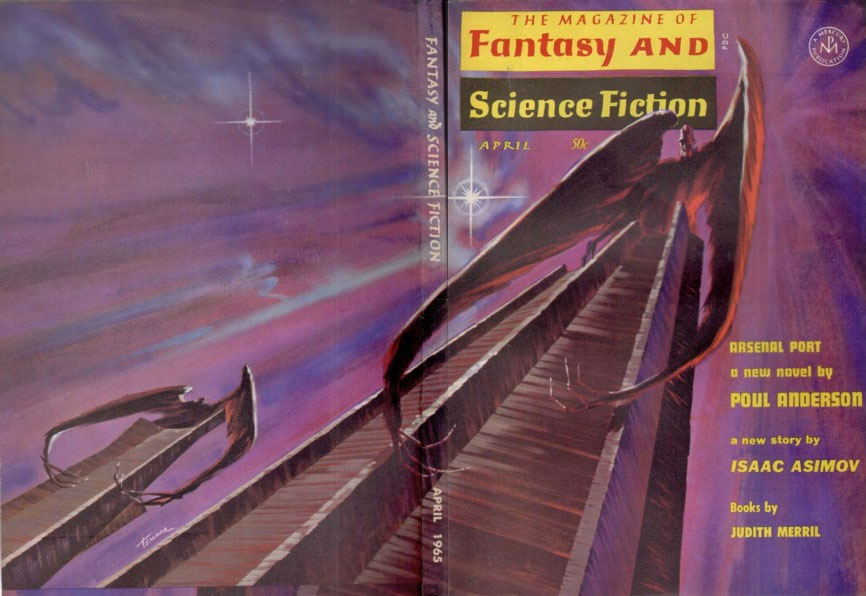

![[April 22, 1965] Cracker Jack issue (May 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650422cover-575x372.jpg)

![[April 18, 1965] The Doctor, the King and the Sultan (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Crusade)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650418cover-672x372.jpg)

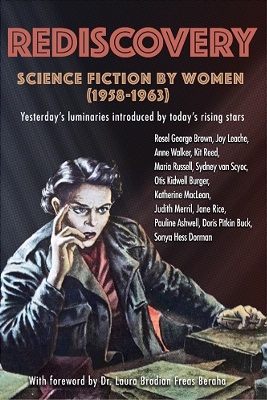

![[Apr. 16, 1965] The Second Sex in SFF, Part VIII](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650416cover-521x372.jpg)

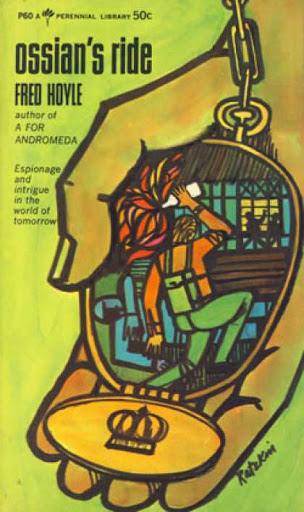

![[April 14, 1965] Furious Time Travel (April Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650414coversnew-672x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1965] Not Long Before the End (May 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650412cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 30, 1965] Suborbital Shots (April 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650330cover-598x372.jpg)

![[March 26, 1965] Digging Up the Past (April 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Fantastic_v14n04_1965-04_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

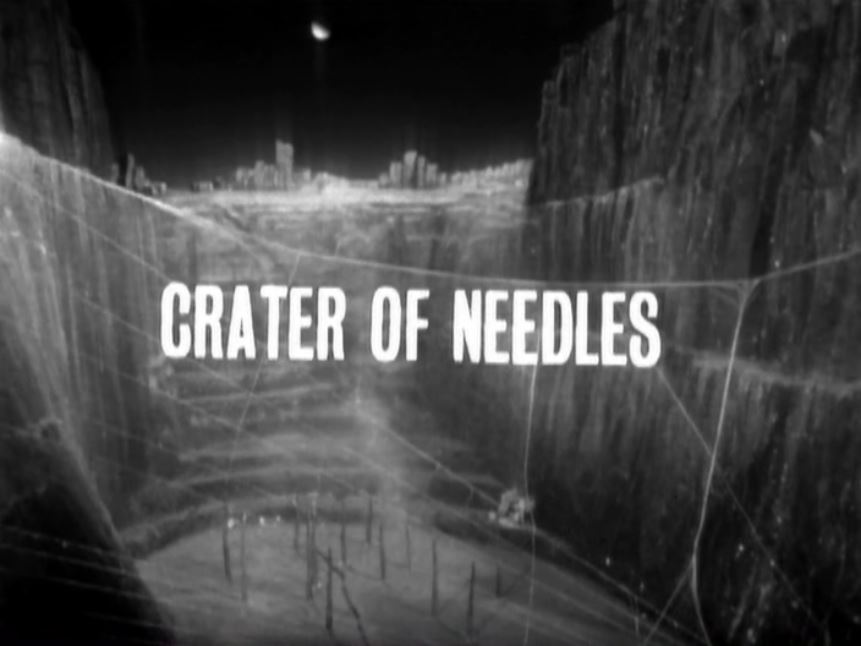

![[March 22, 1965] To Bee Or Not To Bee? (Doctor Who: The Web Planet [parts 4-6])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650322jellyfish-672x372.jpg)

![[Mar. 18, 1965] Per Aspera (April 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650318cover-672x372.jpg)