by Gideon Marcus

A Storm is Coming

"These are the times that try men's souls"

Thomas Paine

The times, they are a changing. If the post-Korea decade was a national honeymoon for the United States, then the tumult following Kennedy's assassination surely marks the dawn of a new era. To be sure, that decade of "good times" was secured in part on the back of many, be they Black, female, and otherwise. Nevertheless, it felt like we, as a country, were moving toward racial justice and equality, toward shared prosperity, toward peace in the world.

Not anymore. Where it seemed there might be rapprochement between East and West, now there is, once again, active American military involvement in Asia. Some 3,000 troops have been dispatched, and the USAF is taking an active role in the campaign rather than simply propping up our South Vietnamese allies (whomever is leading them this week).

The Chicago Tribune says the national mood is tilting in favor of this involvement, a recovery from dashed morale just a few weeks ago after several Viet Cong incursions. At the same time, the peace movement, which I wholly endorse, has also picked up steam, viz. the sit-in of 11 protesters at the White House last week. I take this as a hopeful sign.

Progress toward civil rights has been a matter of two steps forward followed by one backward. The "backlash" against newly won Black rights was in full display on March 7 when uniformed police brutally shut down a planned march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Quickly dubbed "Bloody Sunday," it was an adamant Southern rejection of the Negro's right to basic humanity.

Even Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s arrival on March 8 could not immediately change affairs, and an attempt made March 9 was blocked at the bridge out of town.

But the South has never lead this nation, not in the 1860s, nor in the 1960s. Those who saw this injustice were appalled, and this disgust reached the highest quarters of government. On March 13, President Johnson declared this restriction of free expression to be "a national tragedy", and on March 15, in an address to the jointly assembled Congress, announced sweeping Voting Rights legislation.

Yesterday, a federal judge set aside restrictions against the march. It will proceed as planned, starting as early as tomorrow or the next day. Again, a sign that we can make it through adversity to our dreams.

Weathering Through

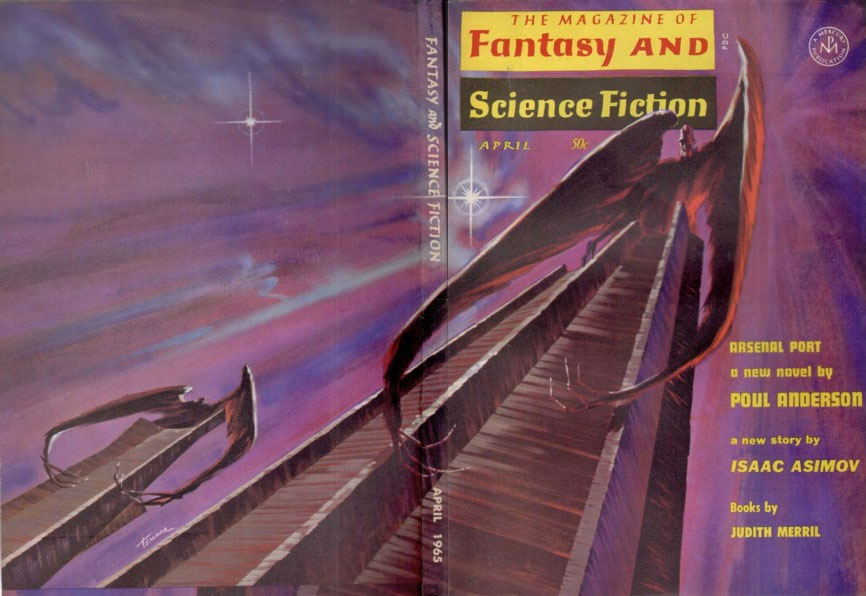

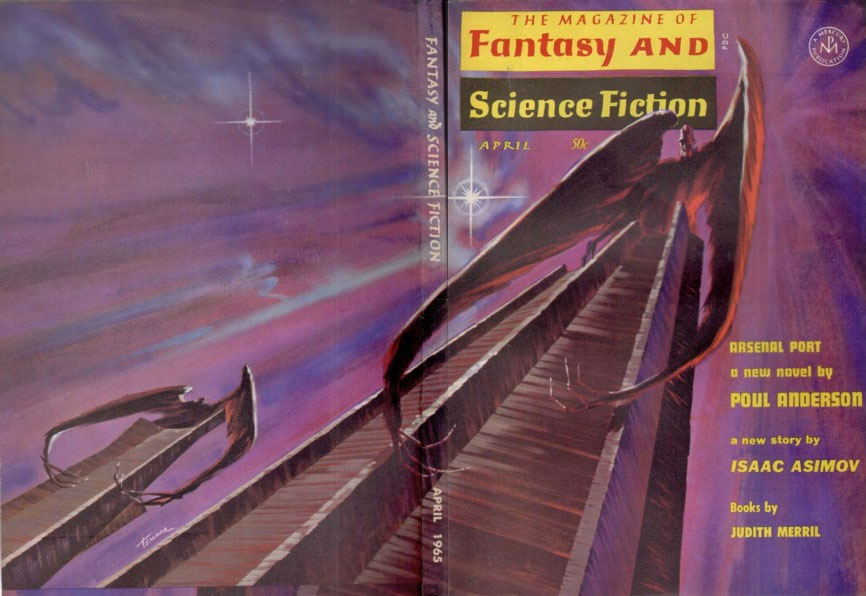

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction has had its own tribulations after a decade of unparalleled excellence under its first two editors. The Avram Davidson era, 1962-64, was something of a nadir for the proud publication. Now that the magazine's owner, Joe Ferman, has taken over the editorial helm (though there are rumors that it's his son, Ed, doing the work), the magazine seems to be pulling out of its nosedive. Come take a look at the latest issue:

by Bert Tanner

Arsenal Port, by Poul Anderson

Once again, Poul Anderson takes the cover with the continuation of the adventures of Gunnar Heim, last seen in January 1965's Marque and Reprisal. The retired space captain had obtained a letter of marque from the French government to harry the Alerion regime, which had taken the Terran planet of New Europe hostage after a short war. Off went Heim to space in the cruiser, Fox 2, along with a scurvy crew, and there the first story ended.

Port takes place on the environmentally hostile planet of Staurm, where Heim has stopped to obtain arms for the trek. Possessed of heavy gravity and a toxic atmosphere, not to mention carnivorous trees and insane battle robots, it is perhaps even more difficult a world than Harrison's Pyrrus.

Complicating matters is the arrival of Heim's ex-lover, a xenobiologist named Jocelyn, who rather pointedly rekindles the affair. But is her love sincere, or is it merely to sabotage Heim's mission in furtherance of the goals of the Peace Party?

On the one hand, this installment is beautifully written, and the depiction of Staurm's weird planetology is hard science fiction at its best. We get a bit more of Heim's background and some nice color on his executive crew, too. On the other hand, Port boils down to a fairly simple adventure trek and doesn't further the main plot. It's roughly analogous to the middle third of Heinlein's Have Spacesuit, Will Travel, which also featured in F&SF. It's enjoyable reading, but you could just as easily skip it.

I waver between three and four stars. I'm going to settle for a high three and wait for the outrage.

F&SF is now experimenting with cartoons. Here's one by Gahan Wilson. There will be others.

Keep Them Happy, by Robert Rohrer

In the future, the death penalty is retained; but in order to be as humane as possible, the condemned are made as happy as possible before the execution. The story begins with a convicted murderer being told he has been acquitted and can go free — before being killed by a blow to the head by Kincaid, the psychologist/executioner-in-chief. The rest of the tale involves a bitter widow who killed her husband for infidelity, and Kincaid, who undertakes to find out what it will take to make her happy.

I found Happy to be disturbing and not a little anti-woman. And, in the end, completely predictable.

It's decently written, however, so it gets a low two star rating.

F&SF by Ed Emshwiller

Imaginary Numbers in a Real Garden, by Gerald Jonas

Here's a cute poem that utilizes mathematical symbols to complete its rhymes. But I fail to see why one looks beyond the stars for complex numbers (you look in electric circuits) and in any event, "i" is the symbol that should have ended the piece.

Three stars.

Blind Date, by T. P. Caravan

Hapless lab assistant is catapulted to the future by a mad scientists, only to find himself immediately made part of festivities celebrating his trip through time.

This tale is the very definition of forgettable; twice, I had to refer to the magazine to remember what this rather goofy tale was about.

Two stars.

The History of Doctor Frost, by Roderic C. Hodgins

Ah, but here's a good one. Frost is a fresh take on the Deal with the Devil genre (indeed, it's stil possible!) On the threshold of making a vital mathematical discovery, Dr. Frost is visited by a servant of Satan who offers to guarantee the man's success if only he will surrender his intellect and abilities to the devil after his demise. Frost demurs and is given 24 hours to make his decision, which he uses to consult with, in turn, a Jesuit Priest, a psychologist, and a female friend. In the end, the decision is entirely Frost's.

It's rather beautifully done, an archetypical F&SF story. Four stars.

Lord Moon, by Jane Beauclerk

Jane Beauclerk is back with another tale set on the nameless world we were first introduced to in July 1964's We Serve the Star of Freedom. Said planet is inhabited by humaniform aliens under the authoritarian regime of the Stars, venerable scholar/tyrants each with their own specialties.

This story involves Lord Moon, a sort of knight, who sails to the lawless twelve thousand islands of Lorran hoping to free and marry the daughter of a Star held captive there. It is not until the end that we have any encounters with actual Terrans, and the whole story is told in a magical legend sort of way. Indeed, it is left an open question whether or not magic works, side-by-side with science, on this particular world.

It's an acquired taste, but I enjoyed it. Three stars, like the last one.

The Certainty of Uncertainty, by Isaac Asimov

Doc A offers up a non-fiction article on quantum mechanics. Such is always a bold decision as it is an abstruse topic that does not lend itself well to popularization. Indeed, Asimov runs into the same problem as everyone else: he doesn't end up explaining it very well.

Having taken quantum mechanics in college (it was very new stuff then), I can tell you that it's not that complicated or difficult to comprehend — provided you have a solid grounding in calculus and second-year physics. Without them, any explanation is just pointless analogy.

I'm not trying to be a snob, and the Good Doctor does do a good job of explaining how tiny things live in a universe of their own, increasingly different from our everyday world as the scale shrinks. But in the end, you're left with a lot of gee whiz stuff and not much understanding.

Three stars.

Eyes Do More Than See, by Isaac Asimov

F&SF's science columnist by-and-large gave up fiction writing with the launch of Sputnik. He still keeps his hand in, every so often, though. Eyes involves energy beings of the Trillionth Century, our long distant descendants, who decide to return to dabbling with physical forms…and quickly discover why they'd given it up.

Apparently, this short-short was originally rejected by Playboy. In any event, it displays a rarely seen poetic side of the author, but whether you'll find it moving or maudlin depends on your particular sensibilities.

I fall right in the middle. Three stars.

Aunt Millicent at the Races, by Len Guttridge

And last, here's a modern-day Welsh fairy tale about a boy whose aunt is transformed into a horse, and how the boy's father exploits the occurrence for financial gain.

Normally, this kind of silly plot would be too trivial to keep my interest, and no doubt played for laughs. Neither is the case. Guttridge's writing, so tight and evocative, so cinematically vivid, makes this my favorite piece of the issue. It misses five stars, but only just.

The Star of Hope

Yes, times are currently tumultuous, and things can often seem hopeless. It's important at junctures like these that we reflect on what's positive in our life, the power we have to make things better, and the security that comes of knowing that things that have gone bad can truly come 'round.

And that's something to celebrate!

New York's Saint Patrick's Day parade, yesterday

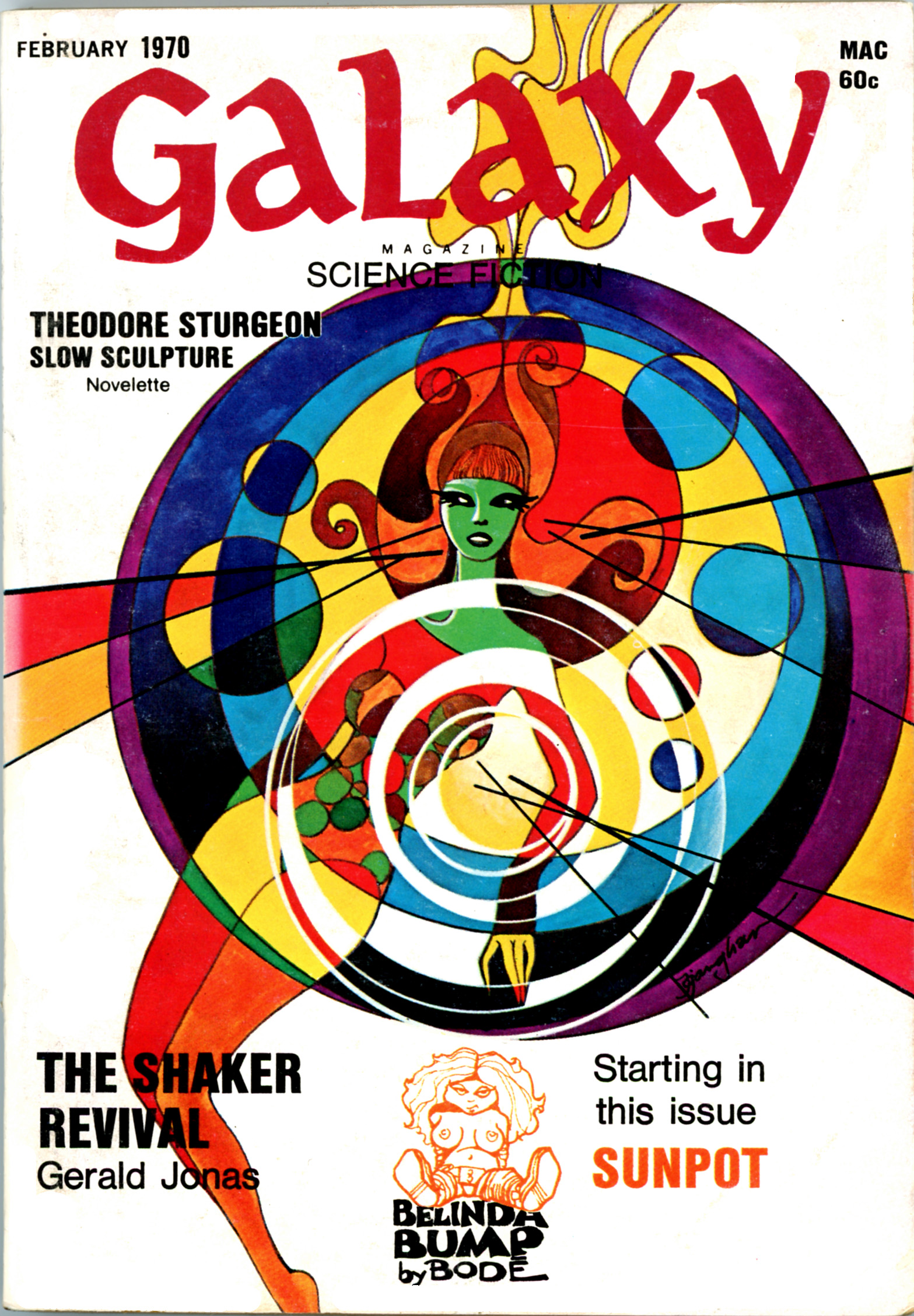

![[January 8, 1970] Slow Sculpture, Fast reading (the February 1970 <i>Galaxy Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700108galaxycover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1967] Field trips (June 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670520cover-449x372.jpg)

![[November 22, 1966] Ha ha. Very funny. (December 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661122cover-661x372.jpg)

![[Mar. 18, 1965] Per Aspera (April 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650318cover-672x372.jpg)