by Gideon Marcus

Of horses and streams

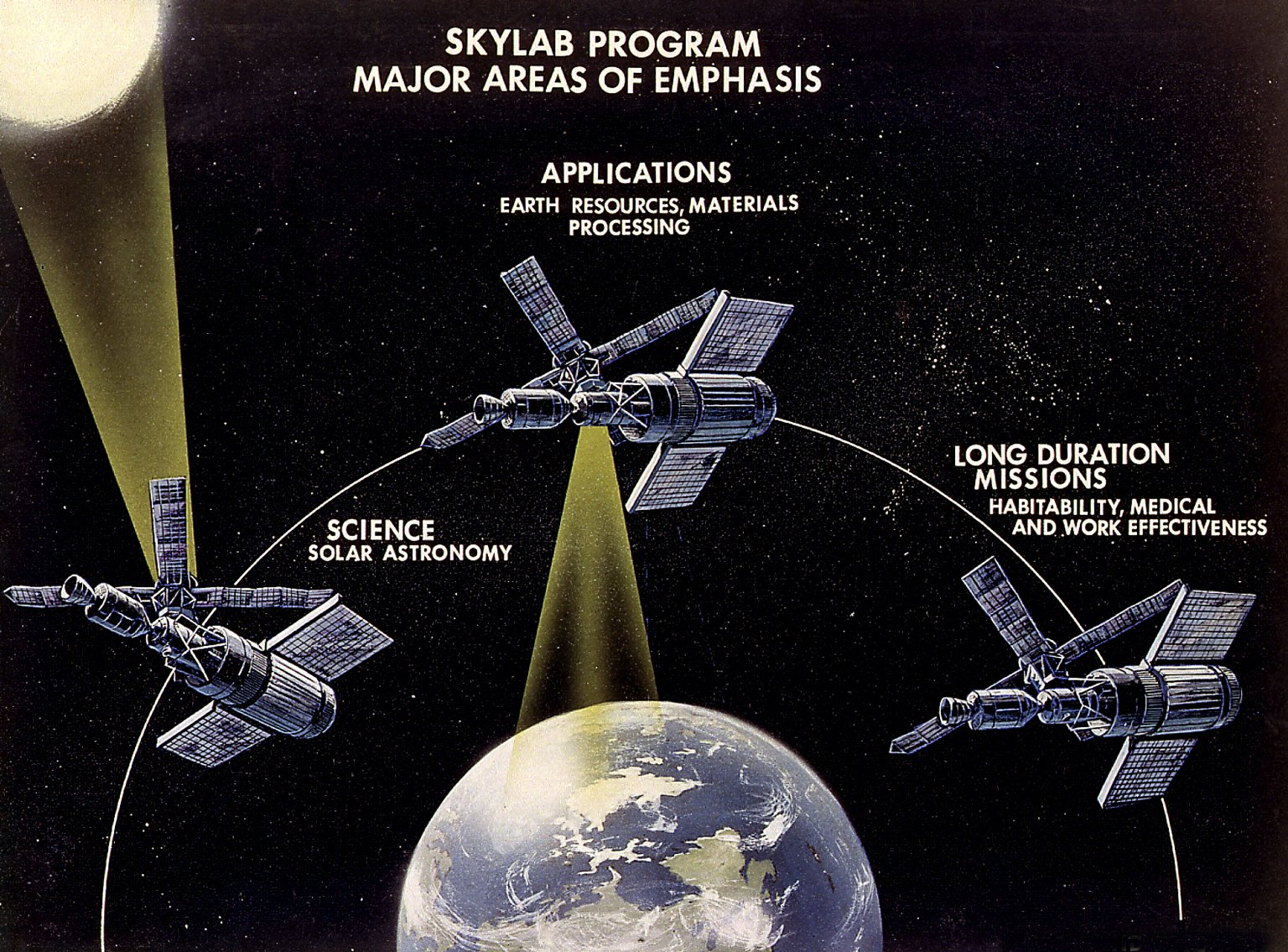

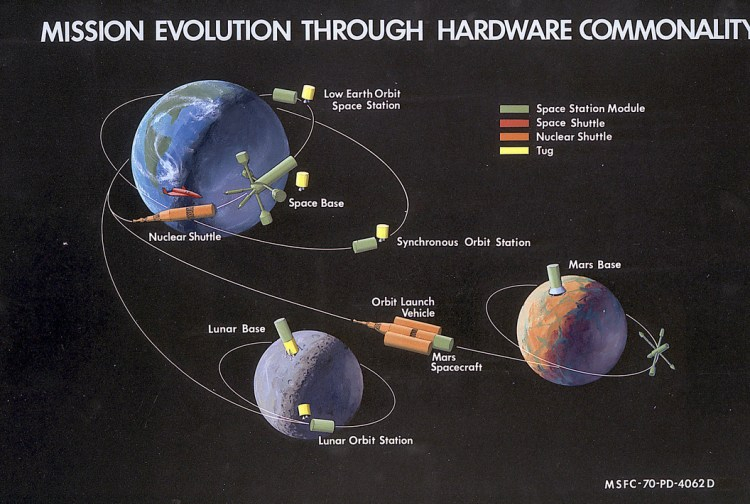

Tom Paine is trying the most desperate of Hail Mary passes. Aviation Weekly just published a piece that the NASA administrator is pitching the idea of an international space station with at least six astronauts from a number of countries, possibly even from behind the Iron Curtain, to be launched in the Bicentennial year of 1976.

The price? Diverting Apollos 15 and 19 to the Skylab program, scheduled to start in 1972, and shifting Apollos 17 and 18 to the new space station. As a result, only two more Apollo missions would fly to the Moon.

There's some logic to this—after all, the Soviets have given up on the Moon, and we've already been twice. Moreover, the Reds are now focusing on orbital space stations (if the recent Soyuz 9 flight and the prior triple Soyuz mission are any indication). Shouldn't we change course, too?

I have to think this idea a plan to save the Space Shuttle. With Senators Proxmire and Mondale sharpening their knives to gut the space agency's budget, Paine figures that the way to keep the next-generation orbital launch vehicle in business is to give it a fixed destination. After all, once the two Apollos have been used, the only way to get astronauts to the station will be on the Space Shuttle.

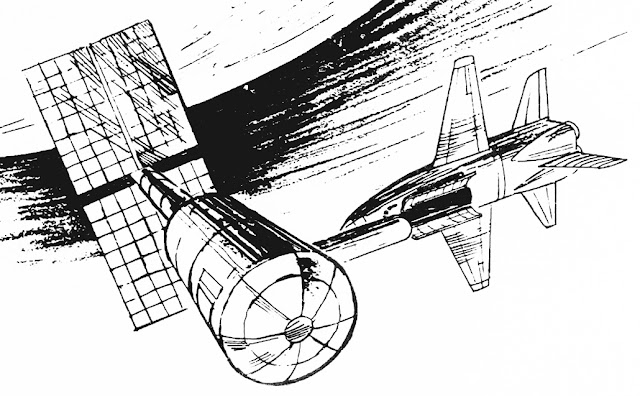

A Space Shuttle Orbiter docks with the NAR Phase B Space Station using a module deployed from its payload bay and linked to the docking port atop its crew cabin. Image credit: North American Rockwell. (text by David Portree)

The timing is awfully tight, though. The Shuttle won't be done until at least 1977, which means the station will have to lie fallow for a while until the vehicle is online. That's assuming the advanced station can even be developed and deployed in six years, which seems doubtful. Skylab is just an adapted Saturn V upper stage. This proposed station would probably be something entirely new.

In any event, it seems foolish to squander Kennedy's legacy and barely scratch the surface of the Moon, scientifically speaking, when an infrastructure for further exploration is already in place. Shifting course so rapidly stinks of desperation. As Walter Matthau once said, playing a gambler in an episode of Route 66, "Scared money always loses."

Of dolphins and dreams

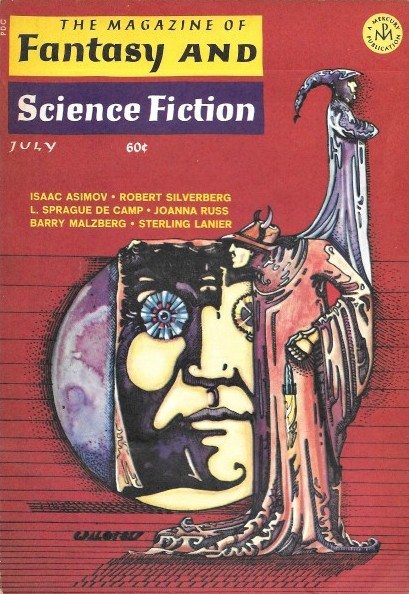

The realm of science isn't the only dubious one this month. Take a gander at the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction to see what I mean…

Cover by Bert Tanner

![[July 20, 1970] The Goat without Horns…among other things (August 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700720fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

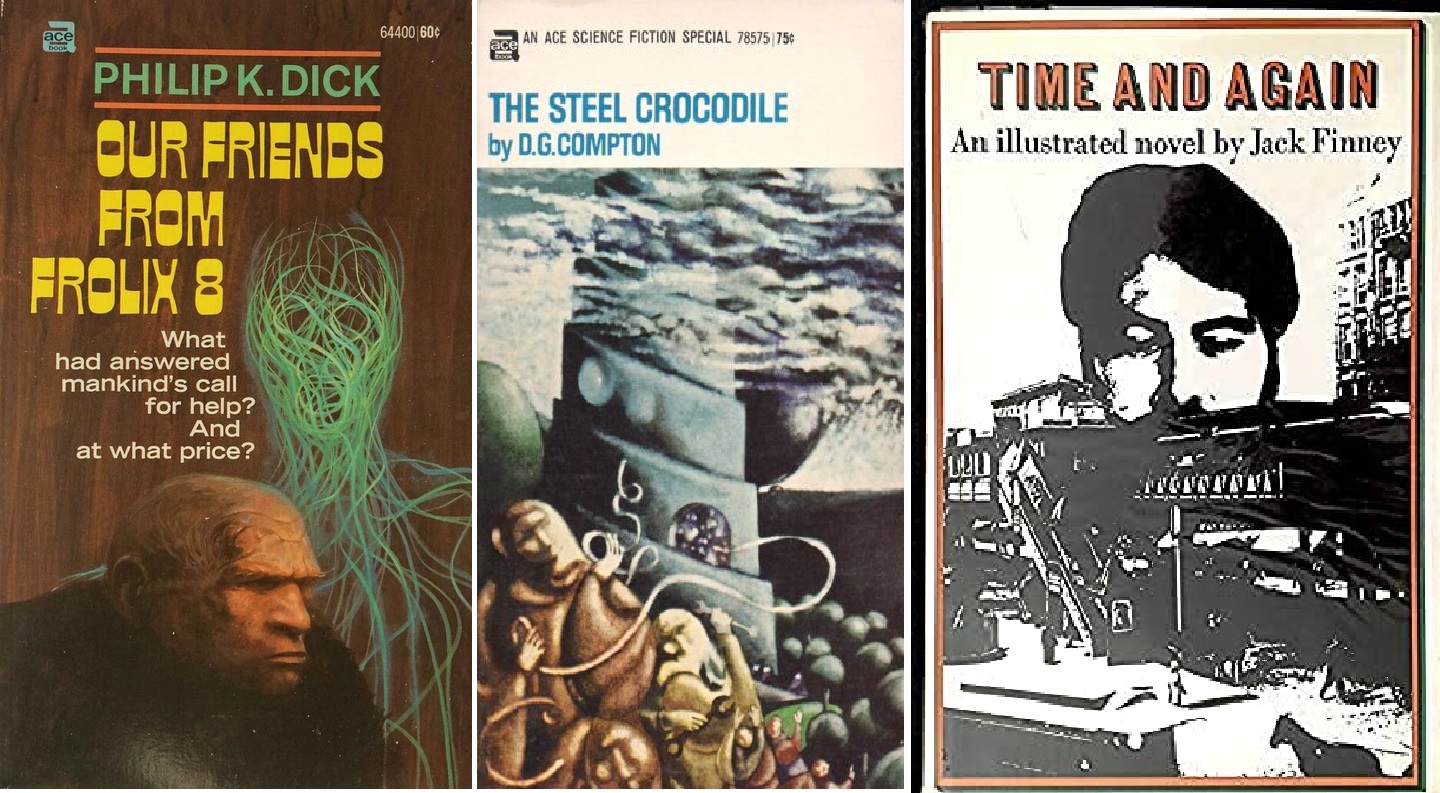

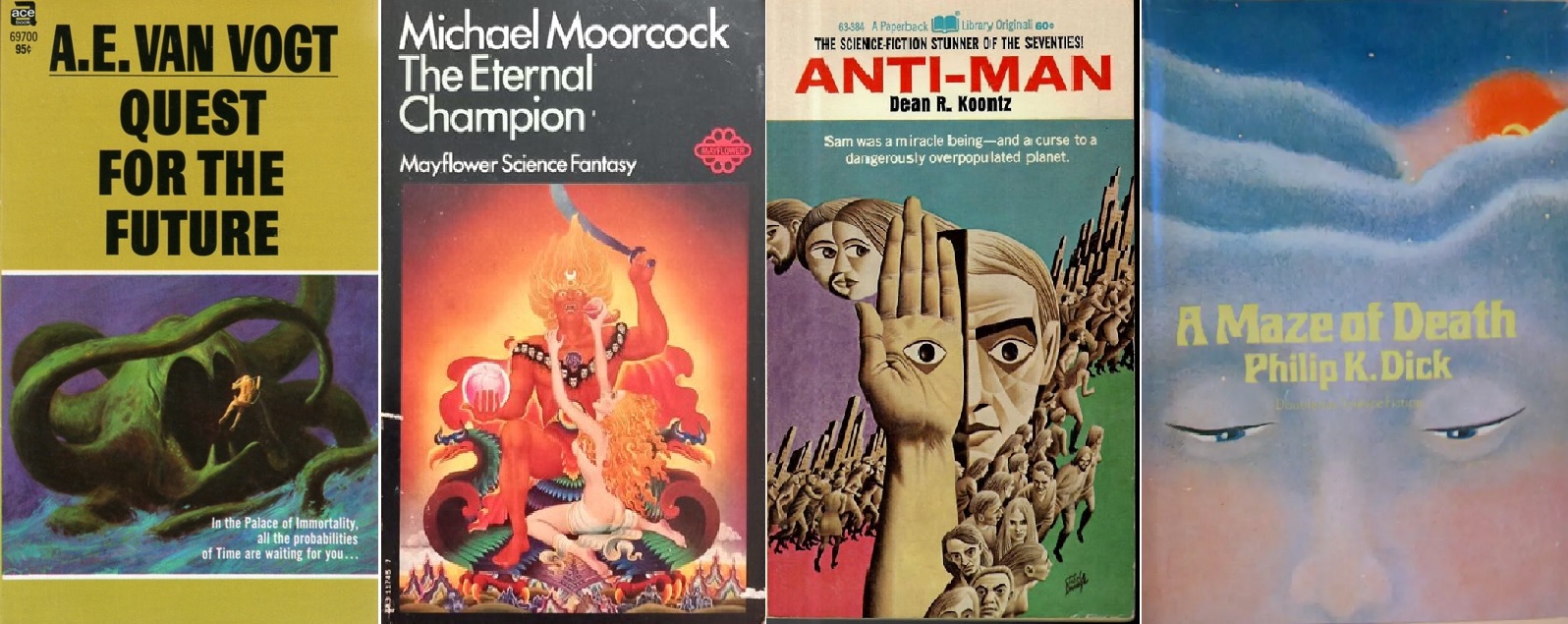

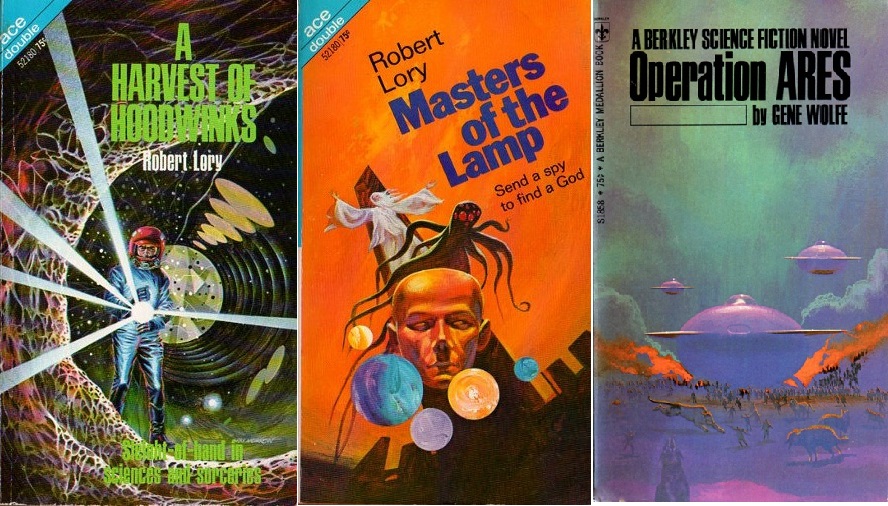

![[July 19, 1970] Dips in road (<i>Maze of Death</i>, <i>The Eternal Champion</i>…and others—July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700719covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1970] Two-star three step (July 1970 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700718covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1970] Journey Behind the Iron Curtain, Journey into Space](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/otherother-672x372.jpg)

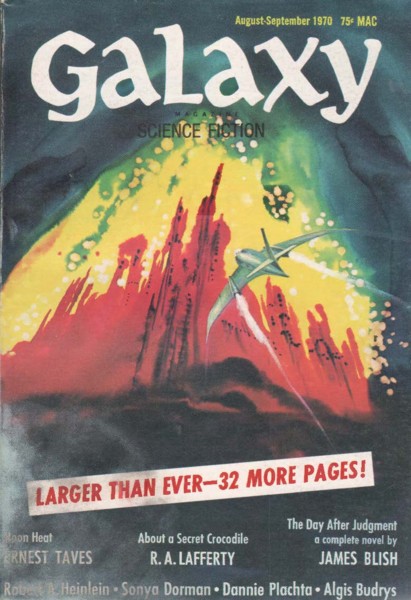

![[July 6, 1970] The Day After Judgment (August/September 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700708galaxycover-411x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Venture-1970-08-Cover-486x372.jpg)

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

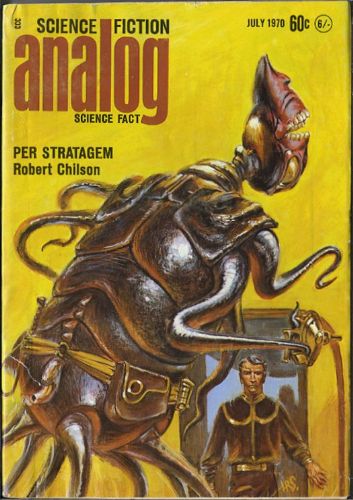

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

![[June 22, 1970] We’ll All Go Together When We Go (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Inferno [Parts 5-7])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700622doom-672x372.jpg)

![[June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/frolix-672x372.jpg)