Seven years ago, the Journey published an article on the Women Pioneers of Space Science. At long last, Kaye offers a much-needed update, this time focusing on the women who helped make Apollo 11's trip to the Moon possible…

by Kaye Dee

Classical literature tells us that the god Apollo was associated with the Nine Muses, the goddesses who inspired the arts, literature and science.

Our modern Apollo program also has its Muses – trailblazing women working behind the scenes in critical areas of the programme. They deserve to be better known, not just for their own impressive careers to date, but also as role models, inspiring girls and young women who might be interested in science, technology, engineering, mathematics or medicine, but are diverted away from them by the prevailing view that careers in these areas are for men, not women.

The famous ‘Dance of Apollo and the Muses’ by the Italian architect and painter, Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi

The famous ‘Dance of Apollo and the Muses’ by the Italian architect and painter, Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi

As someone who has had to contend with these stereotypes myself, trying to establish a career in the space sector in Australia, I thought it might be interesting this month to delve into the stories of four of the women working behind the scenes in the Apollo programme: modern-day daughters of Urania, the Muse of Astronomy, Mathematics and the “exact sciences”.

The “Return to Earth” Specialist: Frances “Poppy” Northcutt

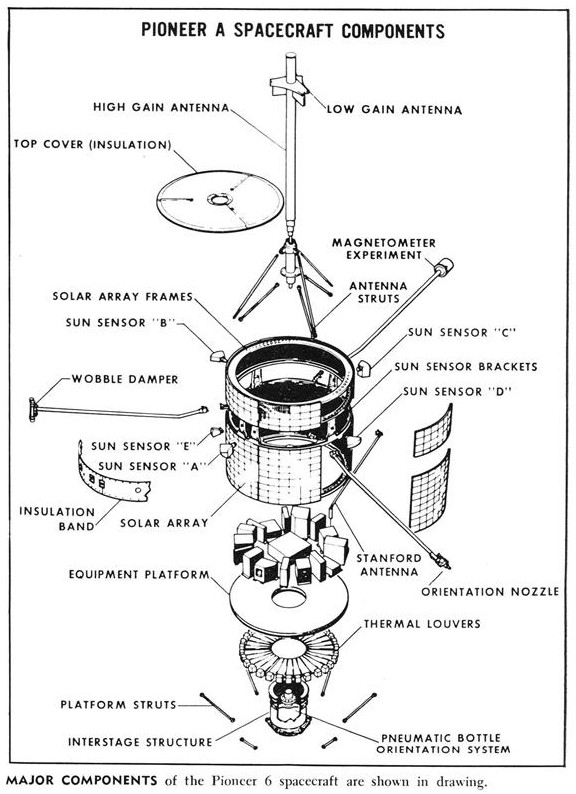

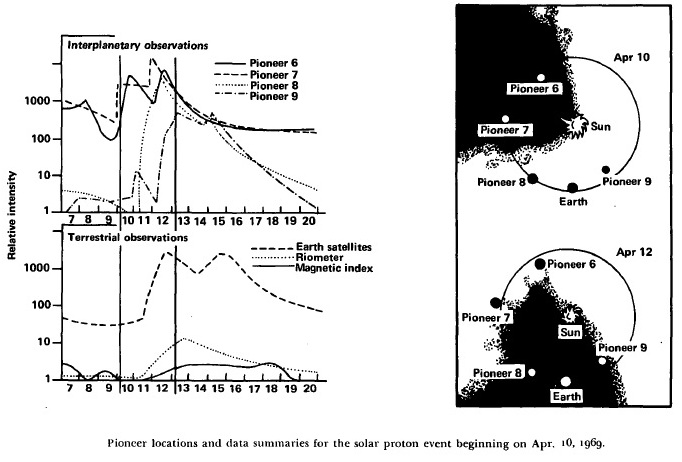

Every aspect of a lunar voyage involves moving objects – the Apollo spacecraft, the Earth and the Moon. Calculating the trajectories required for an Apollo mission to meet and go into orbit around the Moon at a particular date and time, is a mind-bending feat. But getting astronauts safely home from the Moon is even more important!

NASA’s specialist in the incredibly complex and precise calculations required to determine the optimal trajectories for the return to Earth from the Moon, minimising fuel and flight time, is Miss Frances Northcutt, who goes by the nickname “Poppy”. She is, perhaps, the only one of these ladies that you might have heard of (at least those of you in the United States), as she was such a “curiosity” during the press and television coverage of the Apollo-8 mission that she has been interviewed many times (and more on this below).

Born in 1943, Miss Northcutt earned a mathematics degree from the University of Texas, then commenced working at TRW in 1965 as a “computress”! Yes, that was her actual job title, although in Australia we’d have just called her a "computer" (a term applied here and in Britain to both men and women doing this kind of intensive calculating work). Miss Northcutt was placed at NASA’s Langley Research Centre, calculating spacecraft trajectories for the Gemini missions. She proved to be so talented in this area that within just six months TRW promoted her to engineering work with its Return to Earth task force, helping to design the computer programmes and flight trajectories to return an Apollo spacecraft from lunar orbit to Earth.

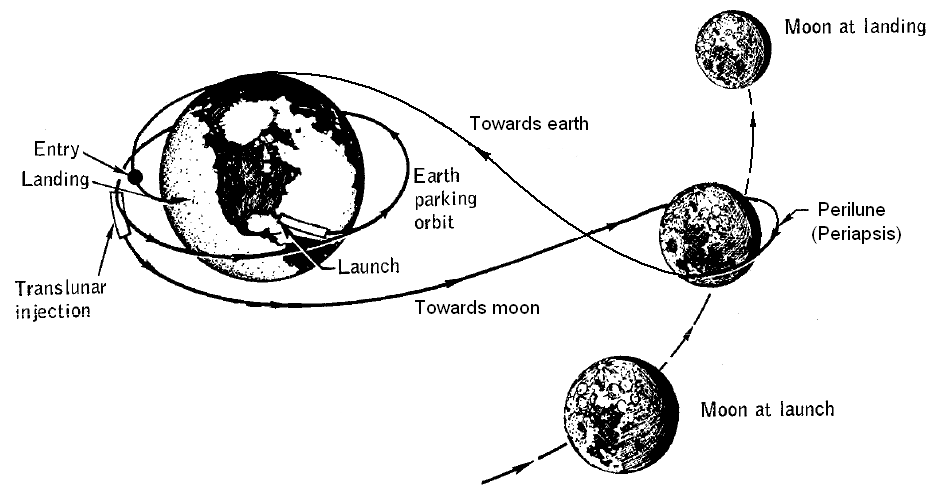

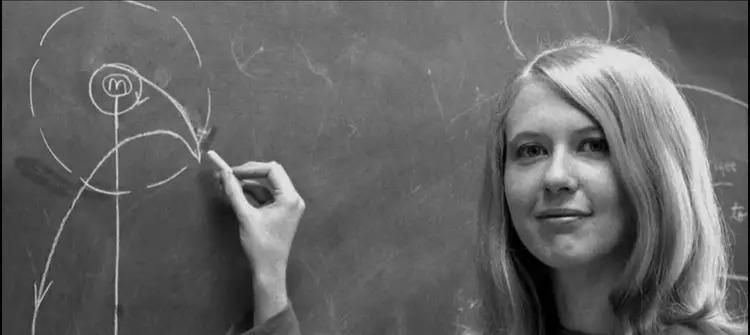

A simplified version of the Apollo lunar free return flight trajectories

A simplified version of the Apollo lunar free return flight trajectories

Poppy Northcutt became the first woman to work in this type of role and was soon undertaking the intricate calculations involved in enabling the Apollo astronauts to travel around the Moon and come safely home. The Moon’s lower gravity changes parameters such as fuel usage, as well as the timing of manoeuvres, so the calculations are particularly tricky. Poppy identified mistakes in NASA’s original trajectory plan, performing calculations that reduced the amount of fuel used to swing around the Moon.

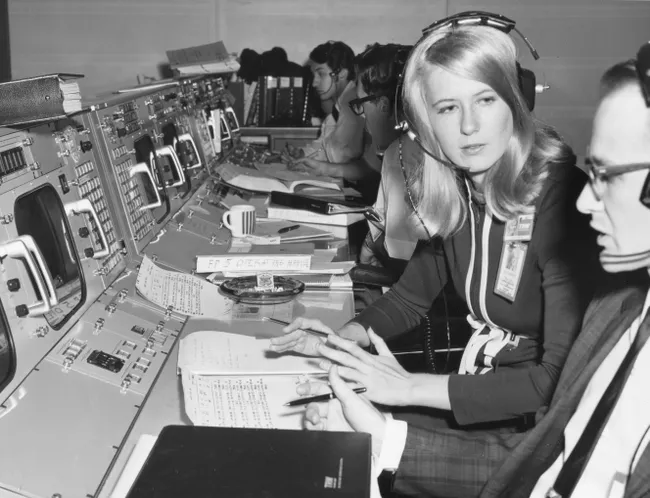

When NASA decided that Apollo-8 would become a lunar orbiting mission, the task force team, including Miss Northcutt, moved to Mission Control to instruct the flight controllers on the trajectory calculations and be available to make real-time calculations and course corrections in the event of unexpected incidents during the flight. Assigned to Mission Control's Mission Planning and Analysis room, Miss Northcutt and her team have been an integral part of Apollo-8, 10 and 11 and are now preparing for Apollo-12. She is the only female engineer in the teams that work in the backrooms of Mission Control in Houston, providing support to the flight controllers.

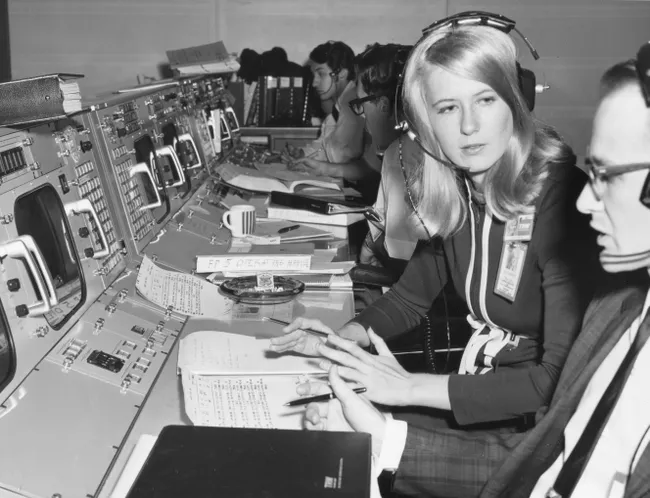

Poppy Northcutt working in the Mission Control support room during Apollo-8

Poppy Northcutt working in the Mission Control support room during Apollo-8

Working Like a Man (but not being paid like one!)

“Computresses” in Miss Northcutt’s original position are classed as “hourly workers”, with their wages capped at working 54 hours per week (in other words, five nine-hour days). Their male counterparts were not only paid more (as we all know, female workers are generally paid between about half and two-thirds of the wages for a man doing the same job), they were also on salaries and paid overtime.

As an ambitious young woman, Miss Northcutt quickly realised that to earn the respect of her male colleagues and be considered a peer, she would have to work the same long hours they did – even if this meant that she was essentially working 10 or more hours a week for no pay!

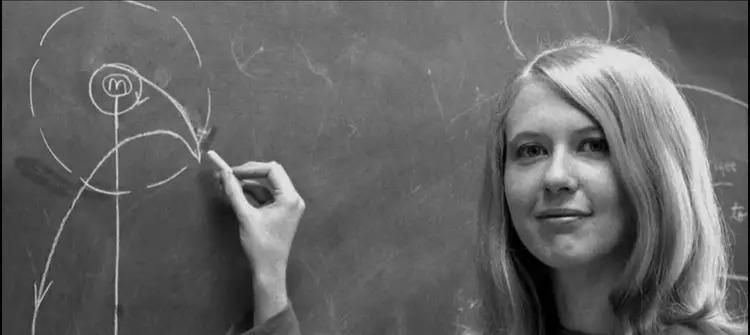

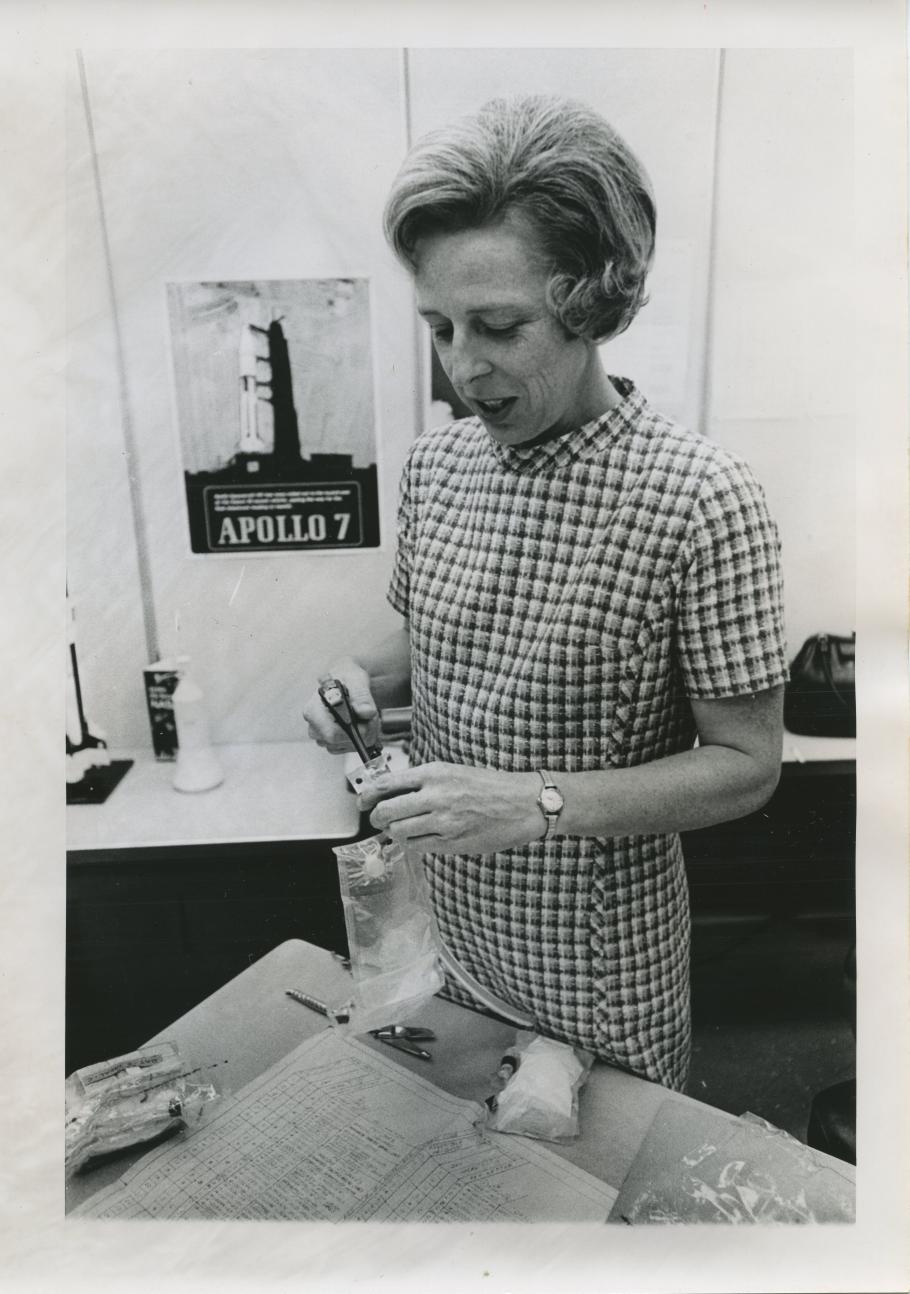

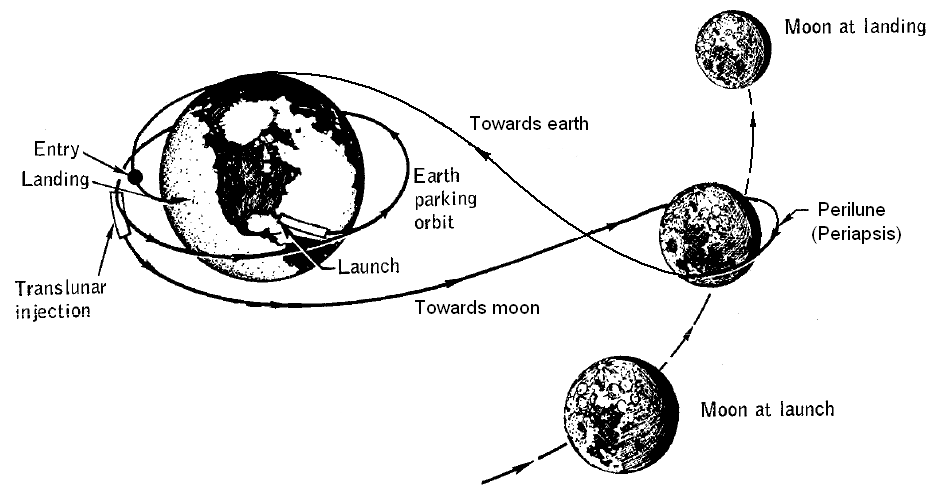

A NASA promotional photo of Miss Northcutt at work in March this year. She presents herself as a diligent professional

A NASA promotional photo of Miss Northcutt at work in March this year. She presents herself as a diligent professional

Her talent and diligence paid off with her promotion to engineer, but, ironically, even though she was still being paid less than her male colleagues, Miss Northcutt tells the story that there was no normal mechanism to approve the pay rise she received with this jump from Computress! Her manager had to keep scheduling the highest possible raise as frequently as he could to bring her up to the full female rate of her new salary.

During Apollo missions, when shifts last around 12 to 13 hours a day in Mission Control, Miss Northcutt usually commences her duty shifts for each mission around the time that the Apollo spacecraft, coasting towards the Moon, prepares to enter the lunar sphere of gravitational influence. During lunar orbit insertion she stands by to assist with new calculations, in the event of an emergency abort, and she reports for duty at Mission Control every day of the lunar phase of the mission and until the astronauts have returned safely to the Earth's sphere of influence. No one can say Poppy Northcutt isn’t pulling her weight, just like a man!

Sexism, Celebrity and Activism

As the only female engineer in Mission Control during the Apollo-8 mission, Miss Northcutt was such a “curiosity” that she received a lot of attention from journalists. While much of this coverage was not seen in Australia, from what I have heard from friends in America, I understand that many of the questions that she received were quite sexist – and even silly.

Miss Northcutt is a very pretty woman and dresses fashionably, so apparently ABC reporter Jules Bergman thought it was more important to ask about her potential to distract her male colleagues from the mission, than to ask about her crucial role: “How much attention do men in Mission Control pay to a pretty girl wearing miniskirts?” Would they have asked a male flight controller if the suit he was wearing turned the heads of the typing pool?! I gather that she gave him a polite brush off response.

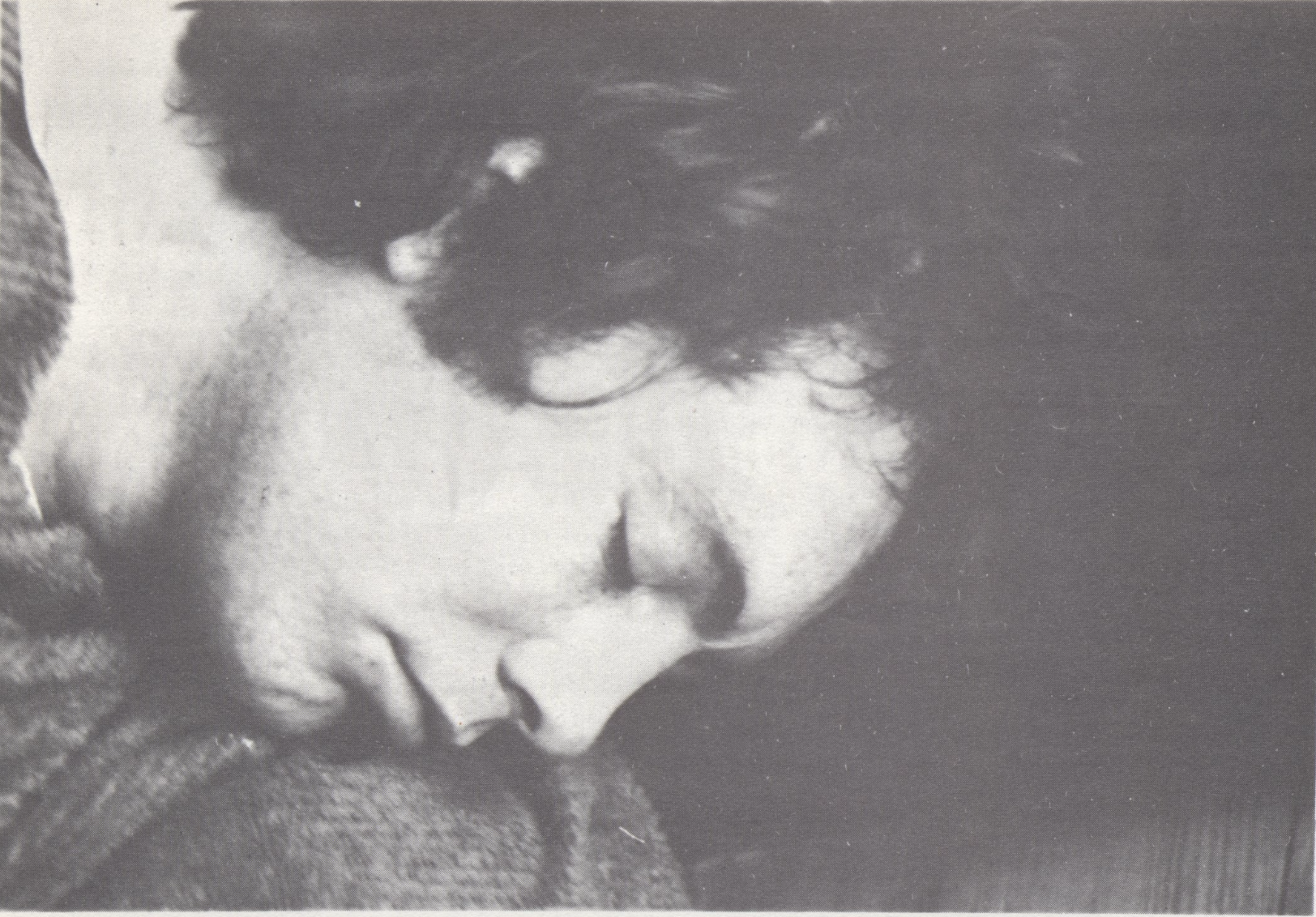

A friend in the US took this photo from her television screen, giving me a glimpse of Mr. Bergman's interview with Miss Northcutt

A friend in the US took this photo from her television screen, giving me a glimpse of Mr. Bergman's interview with Miss Northcutt

It is bad enough when reporters focus on her appearance and ask her such inane questions, while she operates at the level of her male colleagues, for far less monetary reward. But Miss Northcutt has also reported an instance in which she discovered that the other flight engineers were covertly watching her on a video feed, from a camera trained on her while she was conducting equipment flight tests.

As a result of her personal experiences with sexism, Miss Northcutt has become a strong advocate for women’s rights, and has joined the feminist National Organisation for Women. Even in her early days at TRW, she worked to improve the company’s affirmative action and pregnancy leave policies. “As the first and only woman in Mission Control, the attention I have received has increased my awareness of how limited women’s opportunities are”, she has said. “I’m aware of the issues that are emerging. Working in this environment I can see the discrimination against women.”

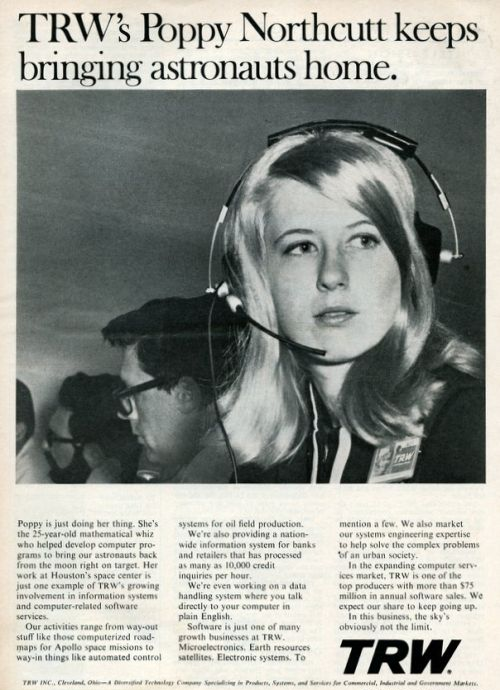

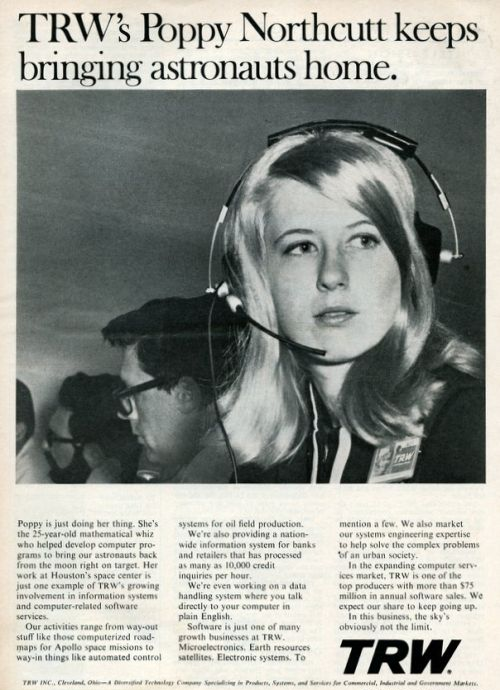

TRW is happy to use Miss Northcutt's minor celebrity to promote itself, but not happy enough to pay her the same salary as her male colleagues!

TRW is happy to use Miss Northcutt's minor celebrity to promote itself, but not happy enough to pay her the same salary as her male colleagues!

However, while she is not pleased that much of the attention she has received has been focussed on her appearance, or treating her as a rare exception to the male-dominated world of spaceflight, Miss Northcutt has said that she recognises that being a woman visibly occupying a critical position in the space programme does send a very positive message to women and girls: a career in science and technology is possible if you want it – and are prepared to work for it!

Miss Northcutt has received letters and fan mail from around the world (including several marriage proposals, it seems!) She has said that she is motivated to continue to advocate for women’s rights in the workplace by the letters she has received from young women, who have said how much she has inspired them.

Whoever Heard of a “Software Engineer”? Margaret Hamilton

The Apollo missions not only need precise trajectories for their lunar voyages – they also need software for their onboard flight computers, which control so many aspects of the flight. If you’re not familiar with this term, “software” describes the mathematical programmes that tell a computer how to carry out its tasks, and a “software engineer” applies the engineering design process to develop software for those different tasks.

The Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming is Mrs. Margaret Hamilton Lickly, who prefers to be known professionally as Margaret Hamilton.I've heard that women in the United States who prefer not to be categorised by their marital status, are now starting to use the designation "Ms.". I don't know if Margaret Hamilton is using this new honorific, but it seems to me appropriate to apply it to her in this article.

33-year-old Ms. Hamilton is another woman playing a crucial role in NASA’s lunar program. Not only is she a pioneer in software engineering, she even coined the term!

Like Miss Northcutt, Ms. Hamilton is also a mathematician, having studied at the University of Michigan and Earlham College. Shortly after graduating in 1958, she married her first husband, James Hamilton, and taught high school mathematics and French, before taking a job in the Meteorology Department at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of technology (MIT) in 1959, a few months before the birth of her daughter.

Ms. Hamilton developed software for predicting weather, and in 1961 she moved to MIT’s Lincoln Lab for the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) Project, adapting weather prediction software into a programme used by the U.S. Air Force to search for potential enemy aircraft. At the Lab, she was the first person to get a particularly difficult programme, which no-one had been able to get to run, to actually work! While working on SAGE, Ms. Hamilton began to take an interest in software reliability, which would pay dividends during Apollo-11’s lunar landing.

A Calculated Move

When Margaret Hamilton learned about the Apollo project in 1965, she wanted to become involved in the lunar programme, and moved to the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, which was developing the Apollo Guidance Computer. She was the first programmer hired for the Apollo work project at MIT and has led the team responsible for creating the on-board flight software for both the Apollo Command and Lunar Modules. She also serves as Director of the Software Engineering Division at the Instrumentation Laboratory.

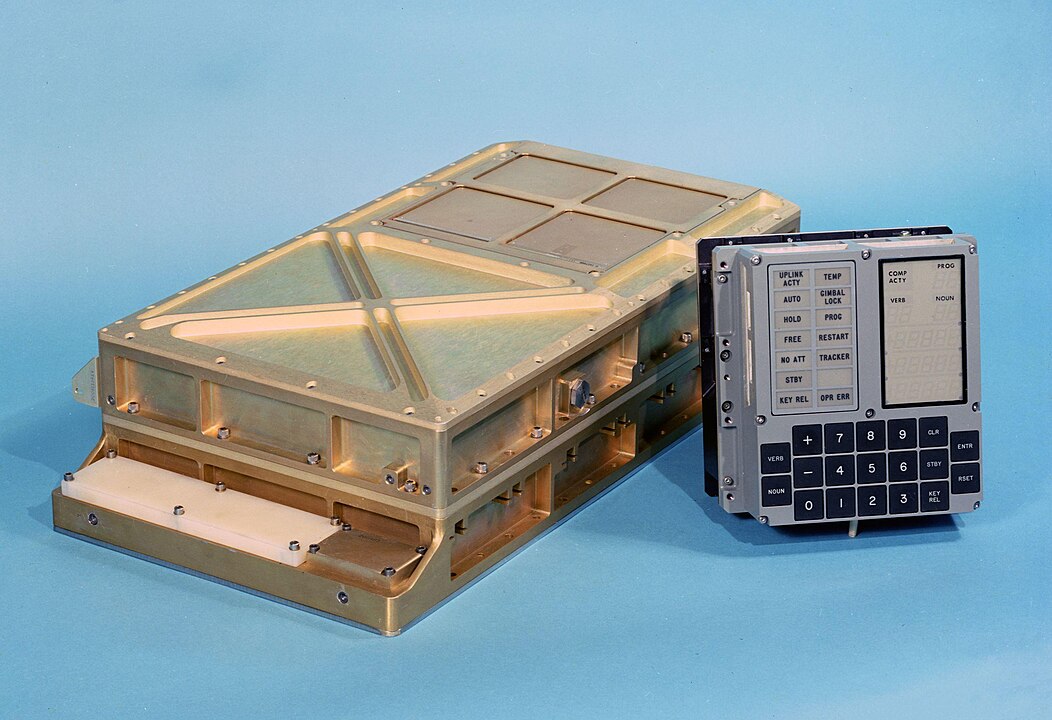

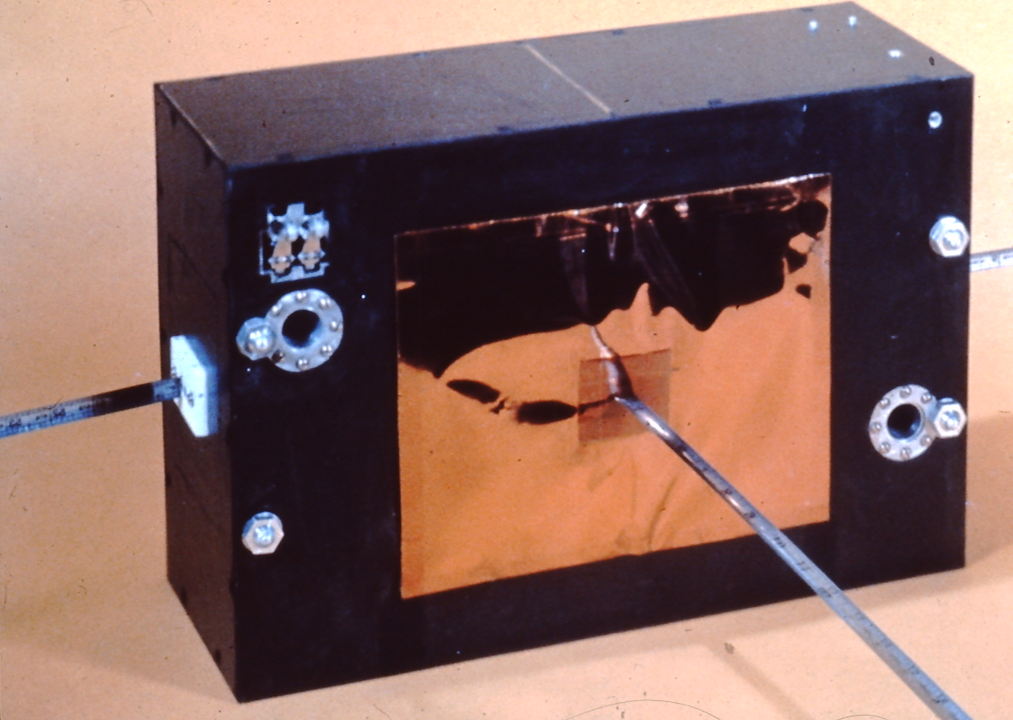

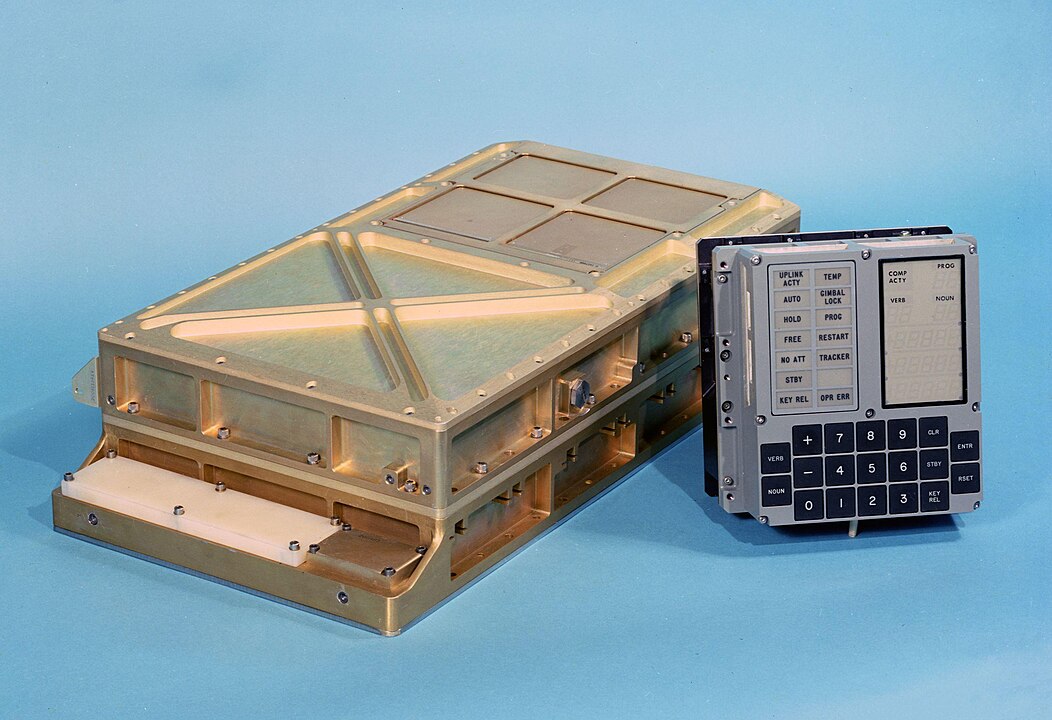

The Apollo Guidance Computer was installed on both the Command and Service Modules. Astronauts communicated with it using a numeric display and keyboard

The Apollo Guidance Computer was installed on both the Command and Service Modules. Astronauts communicated with it using a numeric display and keyboard

While working on the Apollo software, Ms. Hamilton felt that it was necessary to give software development the same legitimacy as other engineering disciplines. In 1966, she therefore coined the term “software engineering” to distinguish software development from other areas of engineering. She believes that this encourages respect for the new field, as well as respect for its practitioners.

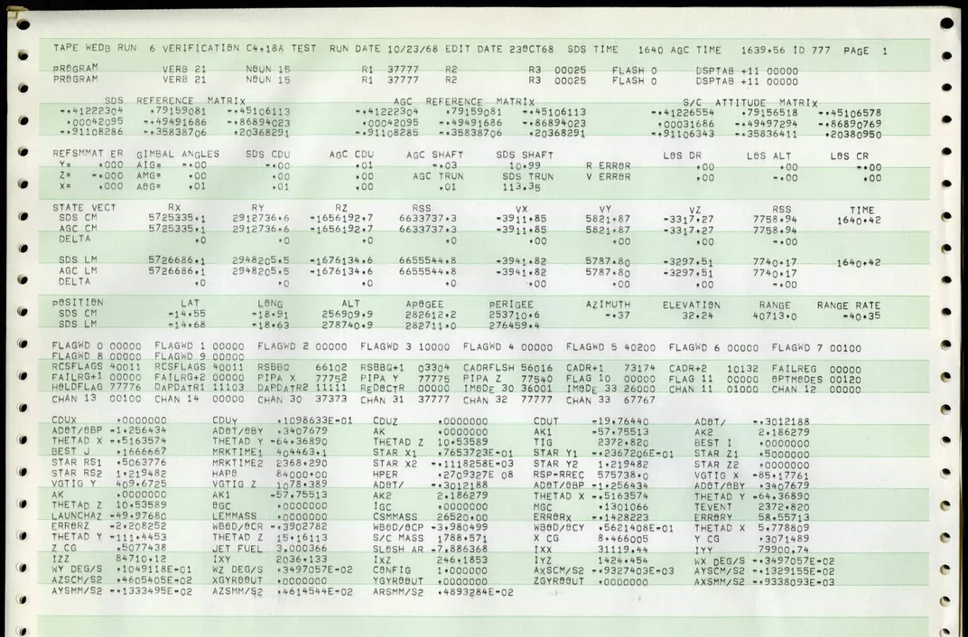

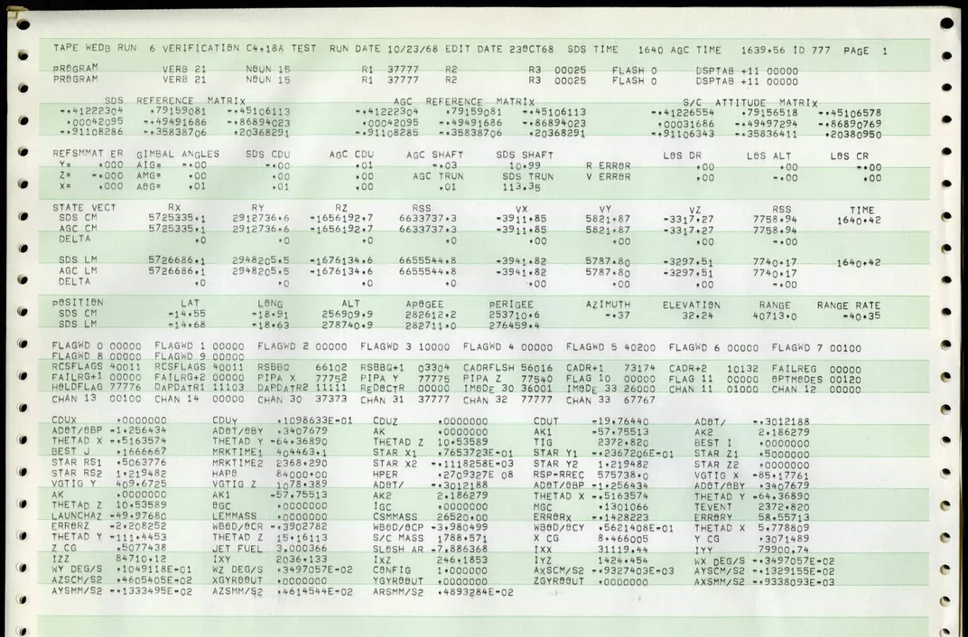

A page from the software for the Apollo Guidance Computer

A page from the software for the Apollo Guidance Computer

On one occasion when her young daughter was visiting the lab, the little girl pushed a simulator button that made the system crash. Ms. Hamilton realised immediately that the mistake was one that an astronaut could make. While Ms. Hamilton has said that she works in a relationship of "mutual respect" with her colleagues, when she recommended adjusting the software to address the issue, she was told: “Astronauts are trained never to make a mistake.” Yet during Apollo-8, astronaut Jim Lovell made the exact same error that her young daughter had!

While Ms. Hamilton’s team was able to rapidly correct the problem, for future Apollo missions protection was built into the software to prevent a recurrence. With her interest in software reliability, Margaret Hamilton insisted that the Apollo system should be error-proof. To achieve this goal, she developed a programme referred to as Priority Displays, that recognises error messages and forces the computer to prioritise the most important tasks, also alerting the astronauts to the situation.

In Part 2 of my series of Apollo-11 articles, we saw how, during the descent to the Moon’s surface, the Lunar Module’s computer began flashing error messages, which could have resulted in Mission Control aborting the landing. However, the Priority Displays programme gave Guidance Officer Bales and his support team confidence that the computer would perform as it should despite the data input overloads that it was experiencing, and that the landing could proceed.

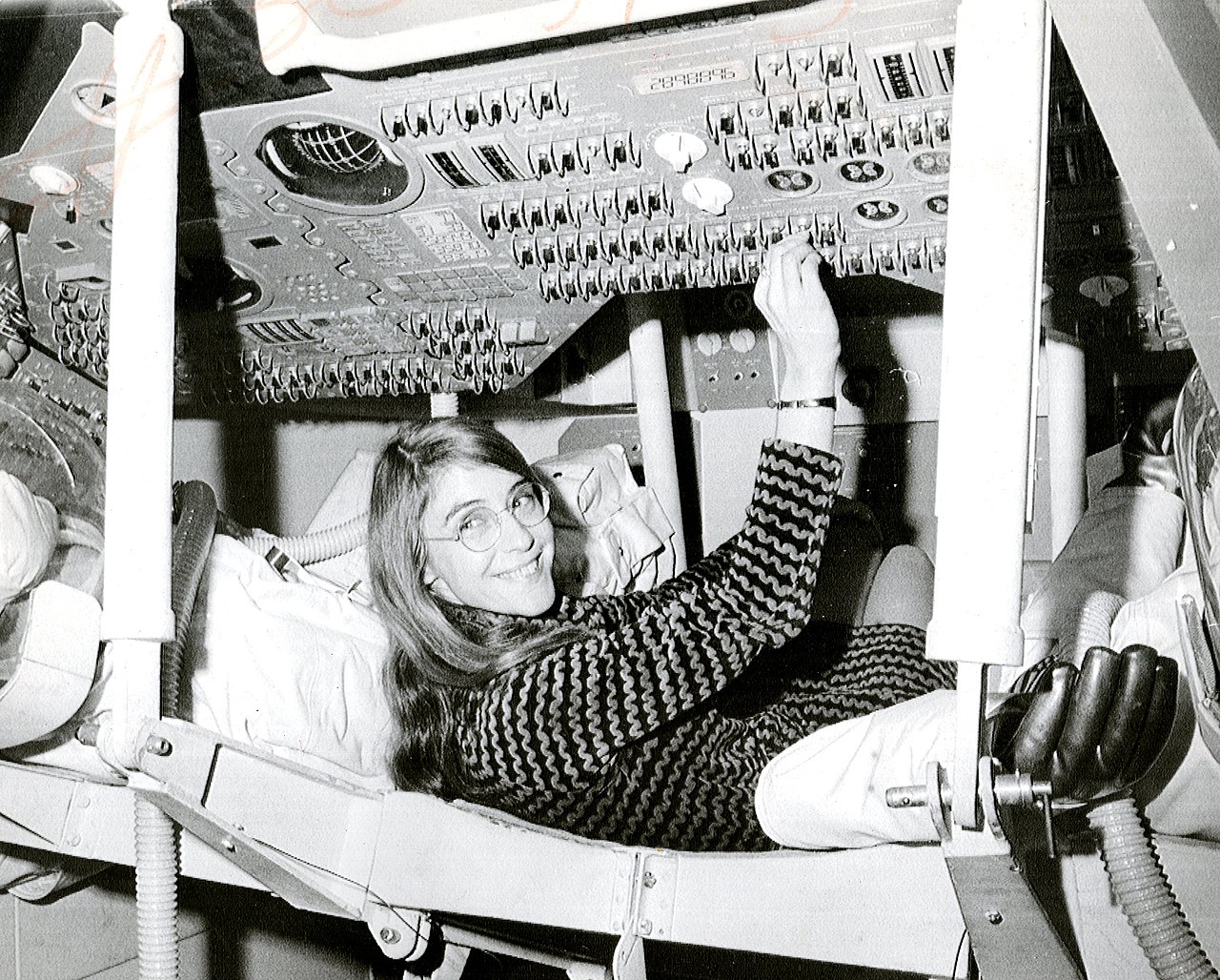

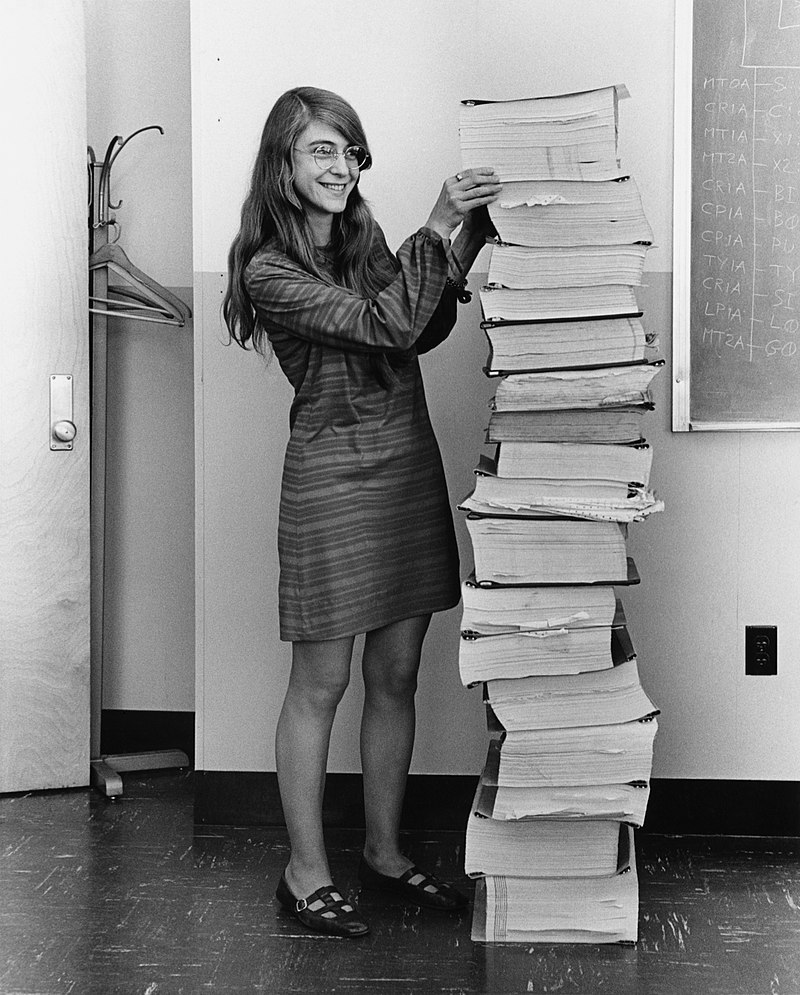

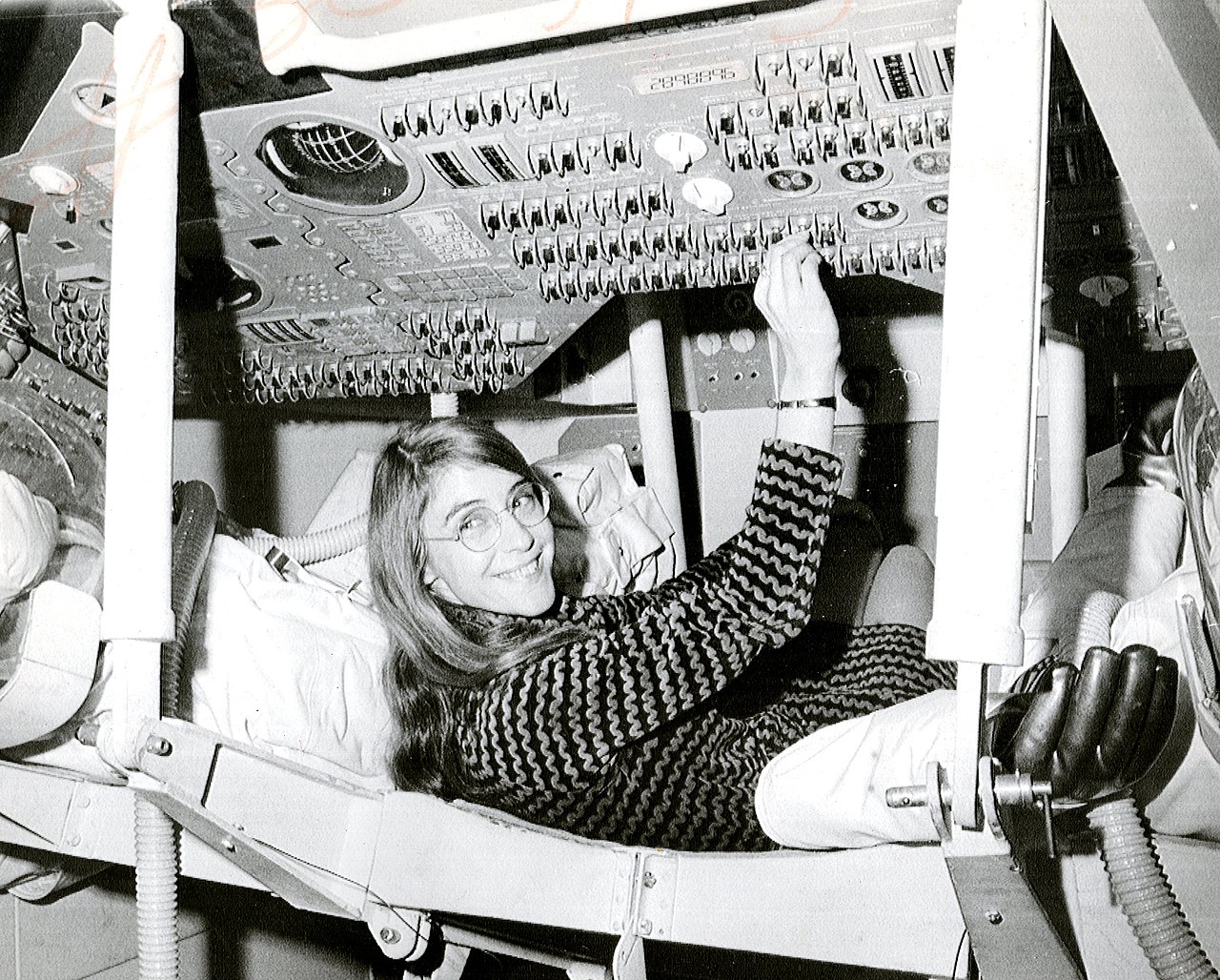

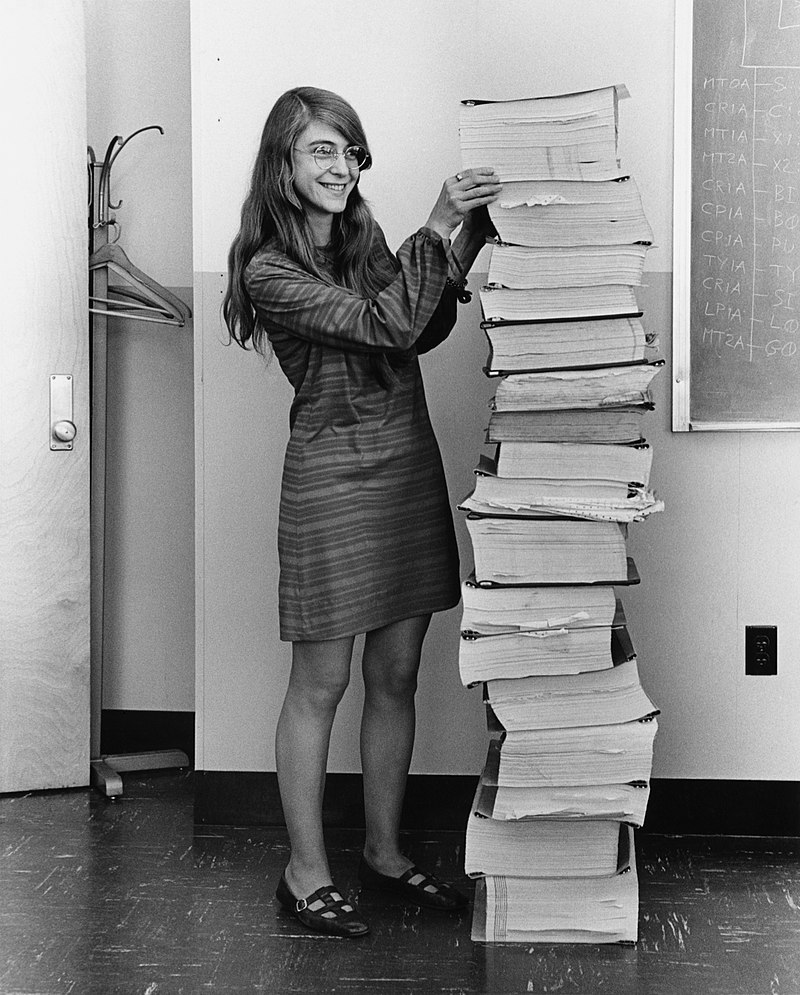

Ms. Hamilton with this year's printout of the entire Apollo Guidance Computer software

Ms. Hamilton with this year's printout of the entire Apollo Guidance Computer software

Ms. Hamilton and her 100-strong team continue to work on developing and refining the Apollo flight software, and I’m sure that they will contribute to whatever future spaceflight projects NASA develops, stemming from Vice-president Agnew’s recently-delivered Space Task Group report to President Nixon.

“I’ve Got Rocket Fuel in my Blood”: JoAnn Morgan

Mission safety and reliability are, of course, critical, but Apollo-11 could not even have made the historic lunar landing if the mission had been unable to launch in the first place! When Apollo-11 lifted off, there was one lone woman in the launch firing team at Kennedy Space Centre’s (KSC) Launch Control Centre, who helped to ensure that would happen – Instrumentation Controller JoAnn Morgan.

JoAnn Morgan watching the lift-off of Apollo-11 from her station in Launch Control

JoAnn Morgan watching the lift-off of Apollo-11 from her station in Launch Control

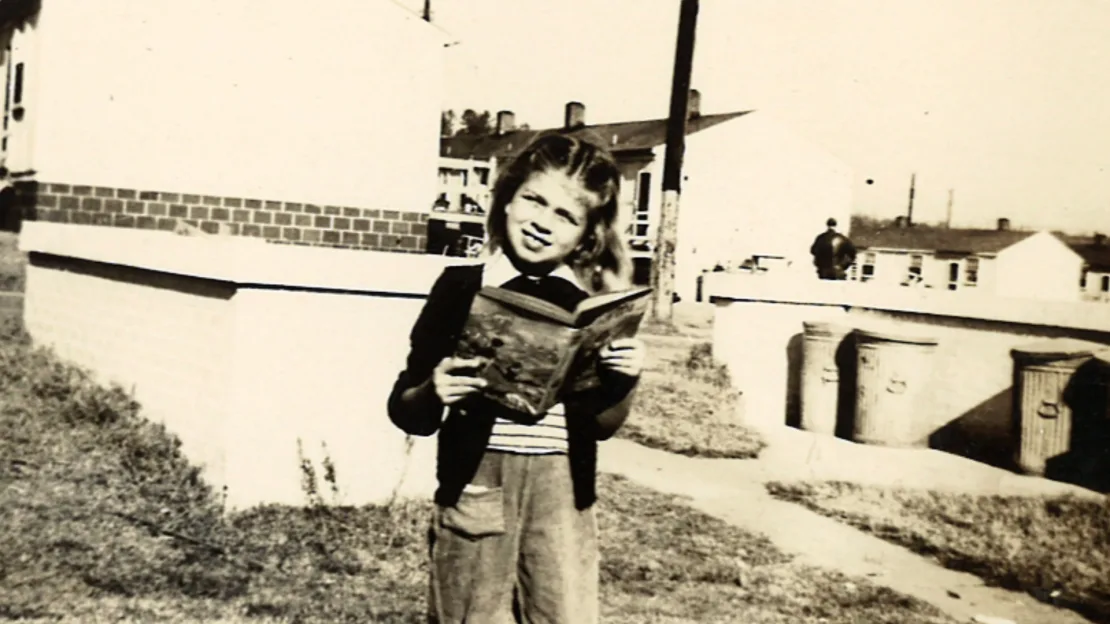

Mrs. Morgan, who was born in December 1940, has described herself as a “precocious little kid” who loved mathematics, science and music, and wanted to become a piano teacher. However, after her family moved to Florida from Alabama, she was inspired by the launch of the first American satellite, Explorer-1, in January 1958, and its significant discovery of the Van Allen Radiation Belts. It was the “opportunity for new knowledge” that space exploration represented that filled the teenager with a desire to be part of the new space programme.

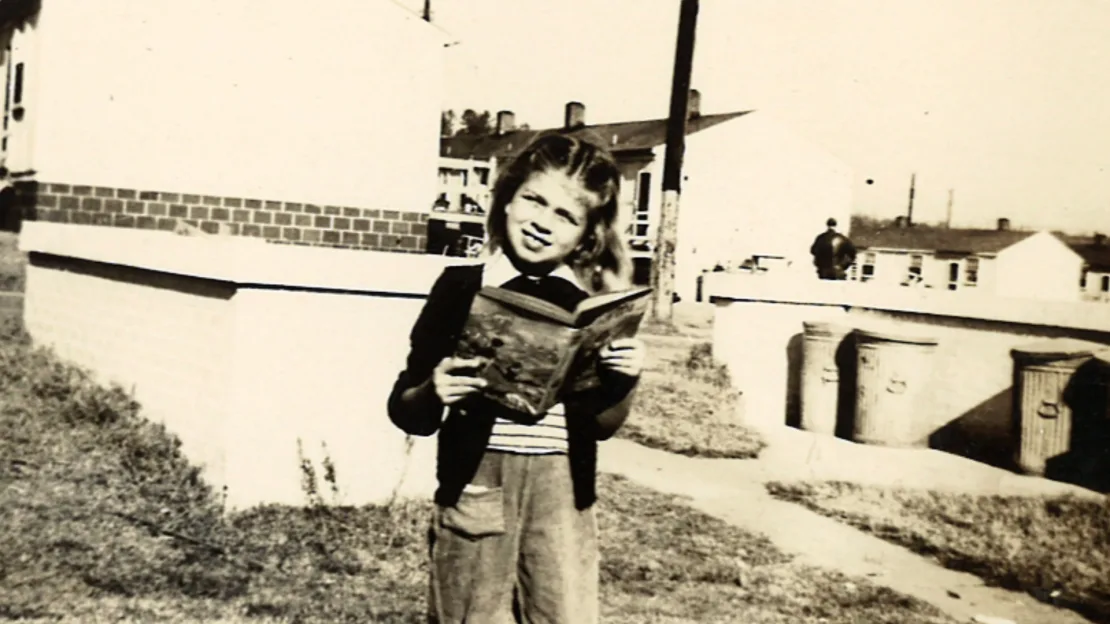

Young JoAnn with one of her favourite books. As a child she loved to read and play with her chemistry set

Young JoAnn with one of her favourite books. As a child she loved to read and play with her chemistry set

Soon after, JoAnn saw an advertisement for two (US) Summer student internship positions, as Engineer’s Aides with the Army Ballistic Missile Agency at Cape Canaveral. As we know, job openings are often advertised separately for males and females, but this ad only referred to “students” (not “boys”), so she took the chance, decided to apply, and was successful thanks to her strong marks in science and mathematics.

So, at just 17, JoAnn Hardin, as she was then, began working as a University of Florida trainee for the Army at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. “I graduated from high school on the weekend and went to work for the Army on Monday. I worked on my first launch on Friday night” is how Mrs. Morgan describes the beginning of her NASA career. The Army programme she was working with became part of NASA when it was established in October 1958.

Supportive Male Mentors

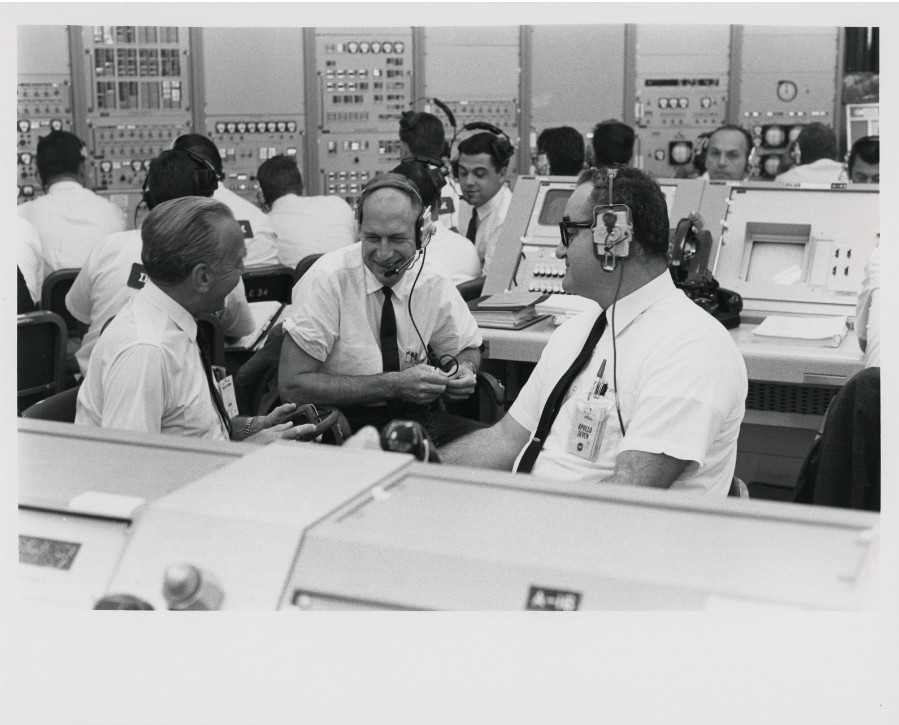

While undertaking her degree in mathematics at Jacksonville State University, Mrs. Morgan continued her Summer internships with the NASA team launching rockets at Cape Canaveral. The young student’s potential did not go unnoticed, and she acknowledges that she received significant support in furthering her career from several senior NASA personnel, including Dr. Wernher von Braun, the chief architect of the Saturn V rocket, Dr. Kurt Debus, the first director of Kennedy Space Centre and Mr. Rocco Petrone, Director of Launch Operations at KSC.

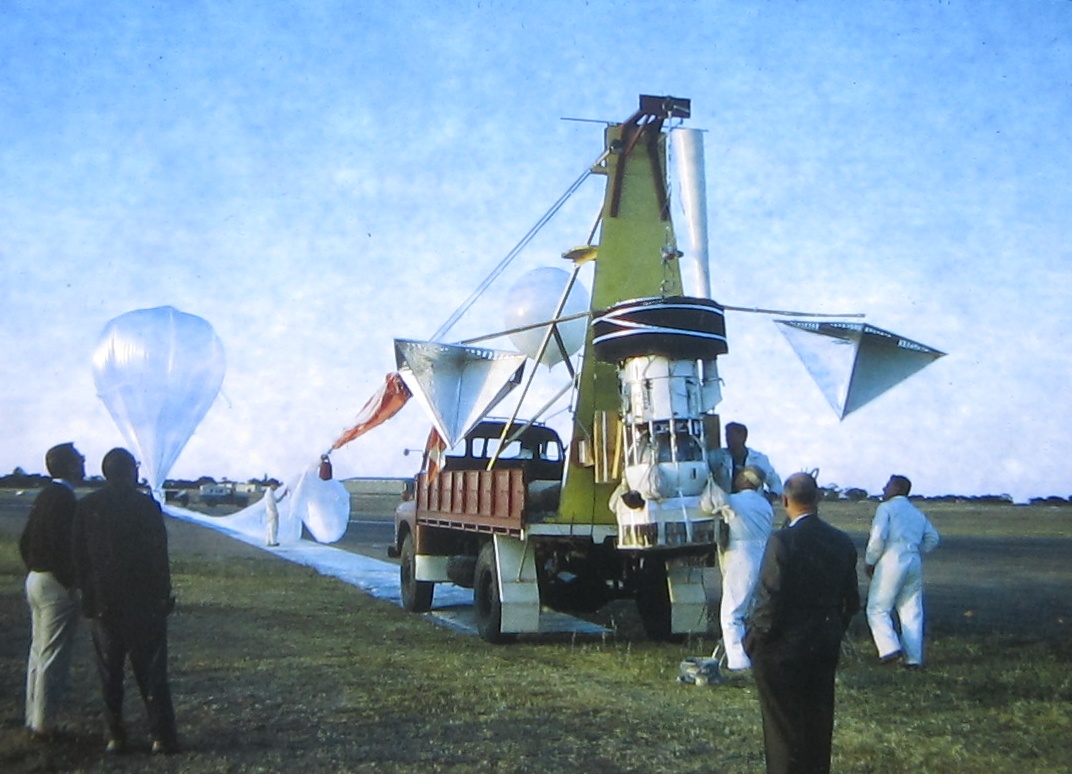

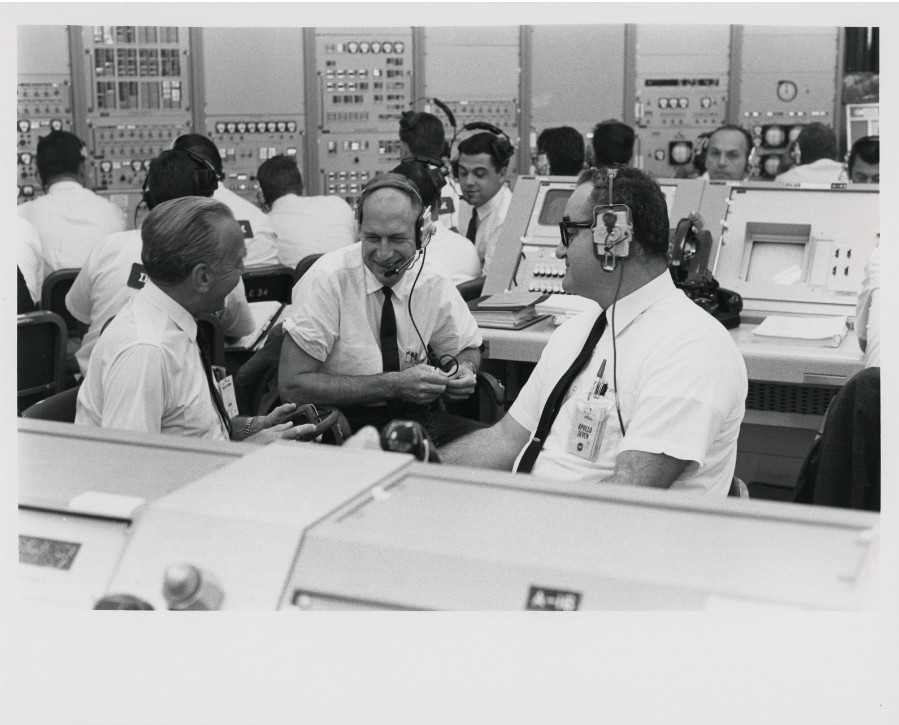

Mentors Kurt Debus, left, and Rocco Petrone, right, during the Apollo 7 flight readiness test in the blockhouse at Complex 34

Mentors Kurt Debus, left, and Rocco Petrone, right, during the Apollo 7 flight readiness test in the blockhouse at Complex 34

Dr. Debus provided Mrs. Morgan with a pathway to becoming an engineer, and she gained certification as a Measurement and Instrumentation Engineer and a Data Systems Engineer, which enabled her to be employed as a Junior Engineer on the launch team. “It was just meant to be for me to be in the launching business,” she says. “I’ve got rocket fuel in my blood.”

As a young woman joining an all-male group, Mrs. Morgan was fortunate that (unbeknownst to her at the time) her immediate supervisor, Mr. Jim White, insisted that the men on the launch team address her professionally, not be “familiar”, and reportedly told them that “You don’t ask an engineer to make the coffee”! (Which, of course, is often a task that falls to the women in any office).

Professional Disrespect

Despite Mr. White’s efforts to create an environment of respect for his first female engineer, Mrs. Morgan has still described experiencing sexism and harassment, treatment similar to the experiences of Miss Northcutt. With no female restrooms in the launch blockhouses at Cape Canaveral, when she needs to use the restroom, she has to ask a security guard to clear out the men’s room so that she can enter. She has reported receiving obscene phone calls at her station (which disappointingly could only have come from colleagues).

However, like Miss Northcutt, while she has said that she sometimes feels a sense of loneliness as the only woman in the team, Mrs. Morgan “wants to do the best job she can” and works the same long hours as her male colleagues. In 1967, as the Apollo programme was ramping up, her dedication to her work had tragic consequences. The stress and long hours of her job contributed to her miscarrying and losing her first child.

The crowded interior of the blockhouse at Launch Complex 34, where Mrs. Morgan has often worked

The crowded interior of the blockhouse at Launch Complex 34, where Mrs. Morgan has often worked

Perhaps the most shocking example of professional disrespect and harassment (which could be considered an assault) that Mrs. Morgan has experienced was during a test being conducted at the blockhouse for Pad 34, where the first Apollo missions were set to be launched. When preparing to acquire some test results, she was actually struck on the back by a test supervisor, who aggressively told her that “We don’t have women in here!” She had to appeal to her own supervisor, Mr. Karl Sendler (who developed the launch processing systems for the Apollo programme) to confirm that she could remain. He told her to disregard the test supervisor and continue with her work (though it’s not clear if any action was taken against the offending supervisor).

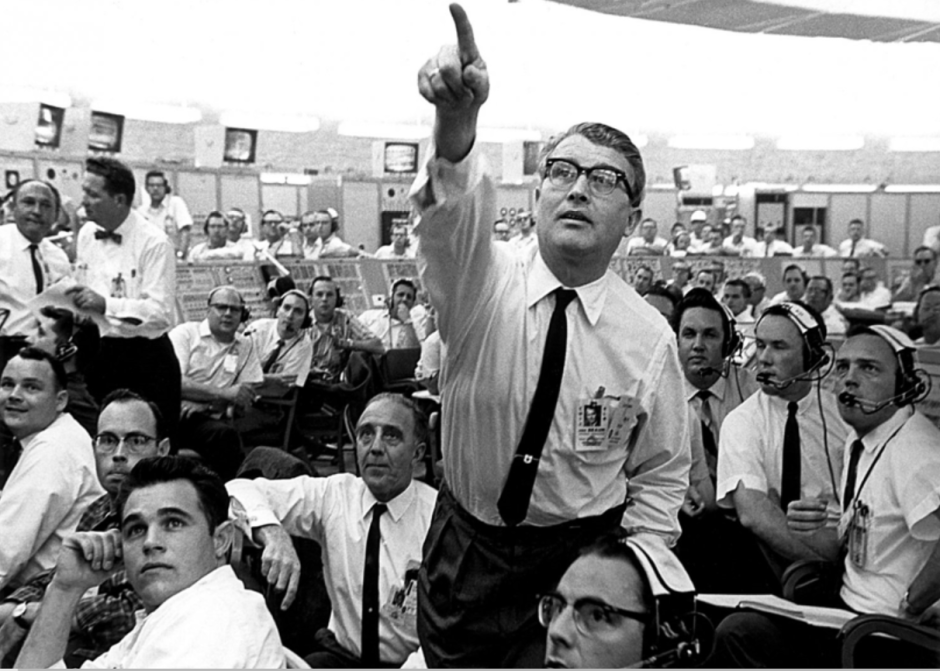

On Console for Apollo-11

The unpleasant incident with the test supervisor prompted many of Mrs. Morgan’s colleagues and senior managers to come forward in expressing acceptance and respect for her as part of the team. Nevertheless, even though she has worked launches for Mercury, Gemini and Apollo, received an achievement award for her work during the activation of Apollo Launch Complex 39, and been promoted to a senior engineer, Mrs. Morgan has frequently found herself rostered for the inconvenient evening shifts. Since her husband is a school teacher and band-leader, this hasn’t always allowed them a lot of time to be together.

Until Apollo-11, Mrs. Morgan was also not selected to be part of the firing room personnel for a launch, usually being stationed at a telemetry facility, a display room or a tracking site for launch. She found this very disappointing, as she always wanted to feel the vibrations from a launch that her colleagues described.

But her desire to experience the incredible shockwave vibrations of a Saturn-V lift-off was finally achieved with the launch of Apollo-11. Recognising that Mrs. Morgan is his best communicator, Mr. Sendler quietly obtained permission from Dr. Debus for her to be the Instrumentation Controller on the console in the firing room for Apollo 11! (This achievement also had the bonus of working day shifts, so that she has been able to spend more time with her husband).

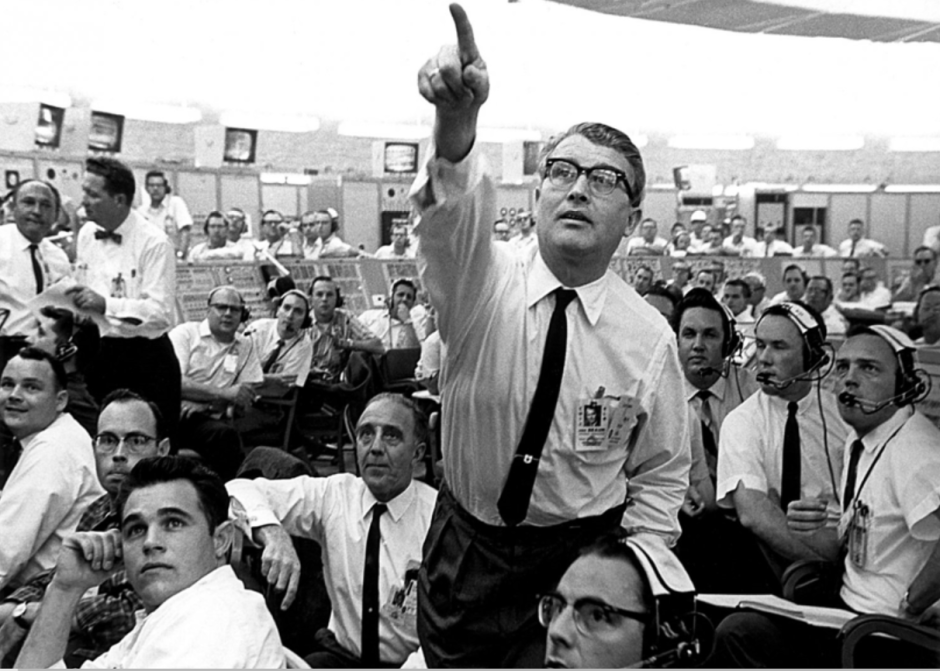

Can you spot the lone woman in a sea of men? In this picture of the Launch Control firing room during Apollo-11, Mrs. Morgan is in the third row, just to the left of centre.

Can you spot the lone woman in a sea of men? In this picture of the Launch Control firing room during Apollo-11, Mrs. Morgan is in the third row, just to the left of centre.

A successful launch is critical to each mission and Mrs. Morgan believes that her prime role in the launch of the historic mission will help to further her career within NASA. Although she has not received the same level of press and television attention as Miss Northcutt, she does hope that even the photos of her in Launch Control – a lone woman in a sea of men – will help to inspire young women to aspire to careers in the space programme, so that, at some time in the future, photos like the ones she is in now “won’t exist anymore.”

Making Packed Lunches for Astronauts: Rita Rapp

You could say that the astronauts are the most fragile component of each Apollo mission. Nutrition is important in keeping crews healthy and functioning during a flight, so space food has to be as appetising as possible, within the constraints of spaceflight and the weightless environment – especially as missions to the Moon, and future space stations and lunar bases will keep astronauts in space for longer and longer periods.

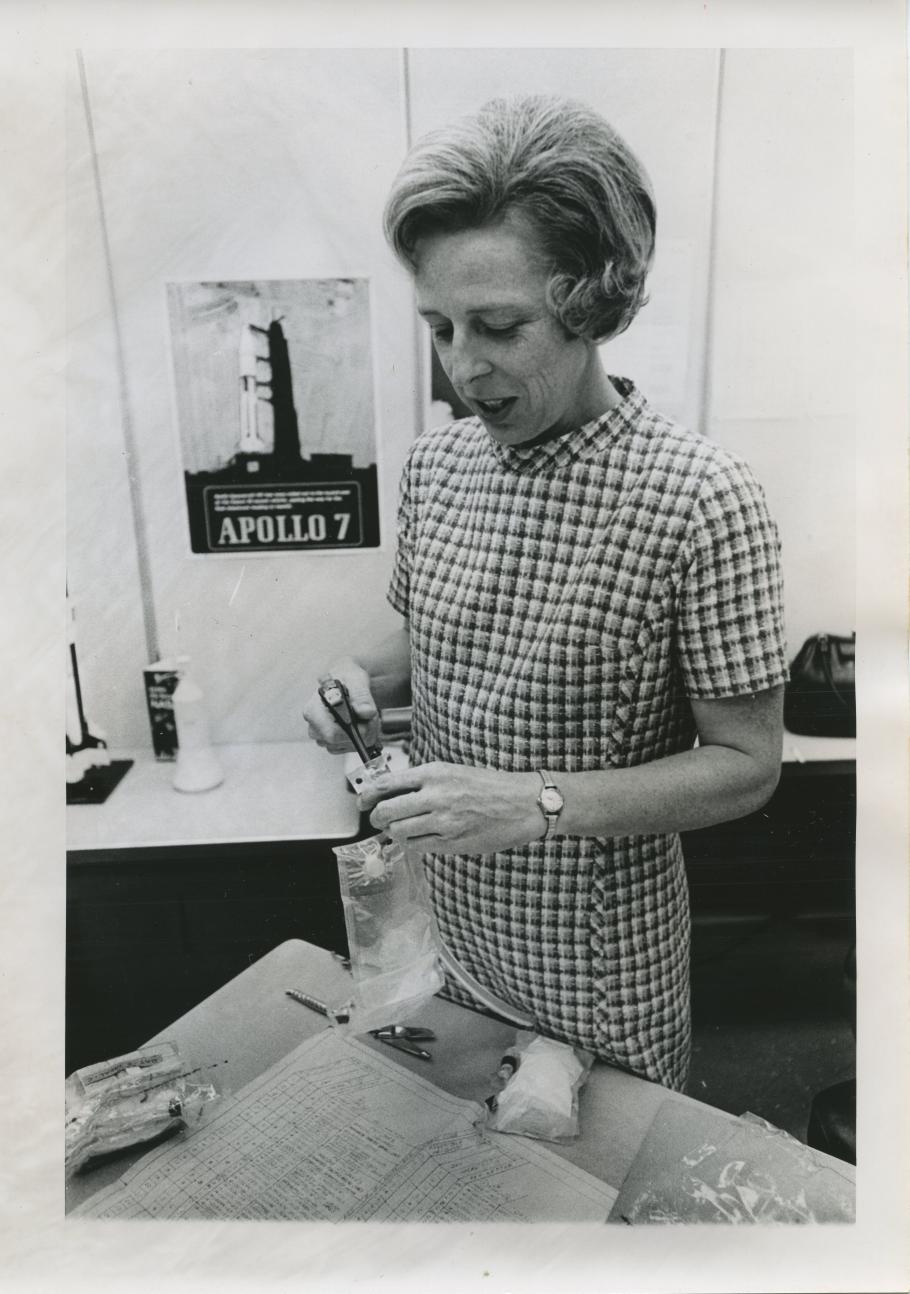

Physiologist Miss Rita Rapp, head of the Apollo Food Systems team, has been looking after the astronauts' bodies – and stomachs – since she joined NASA in 1960. For the Apollo programme, she has developed the space food and food stowage system designed to keep the astronauts supplied with the right mix of calories, vitamins, and nutrients to enable them to function well in space. One of her goals has been to ensure that crews have something worth eating during their spaceflights.

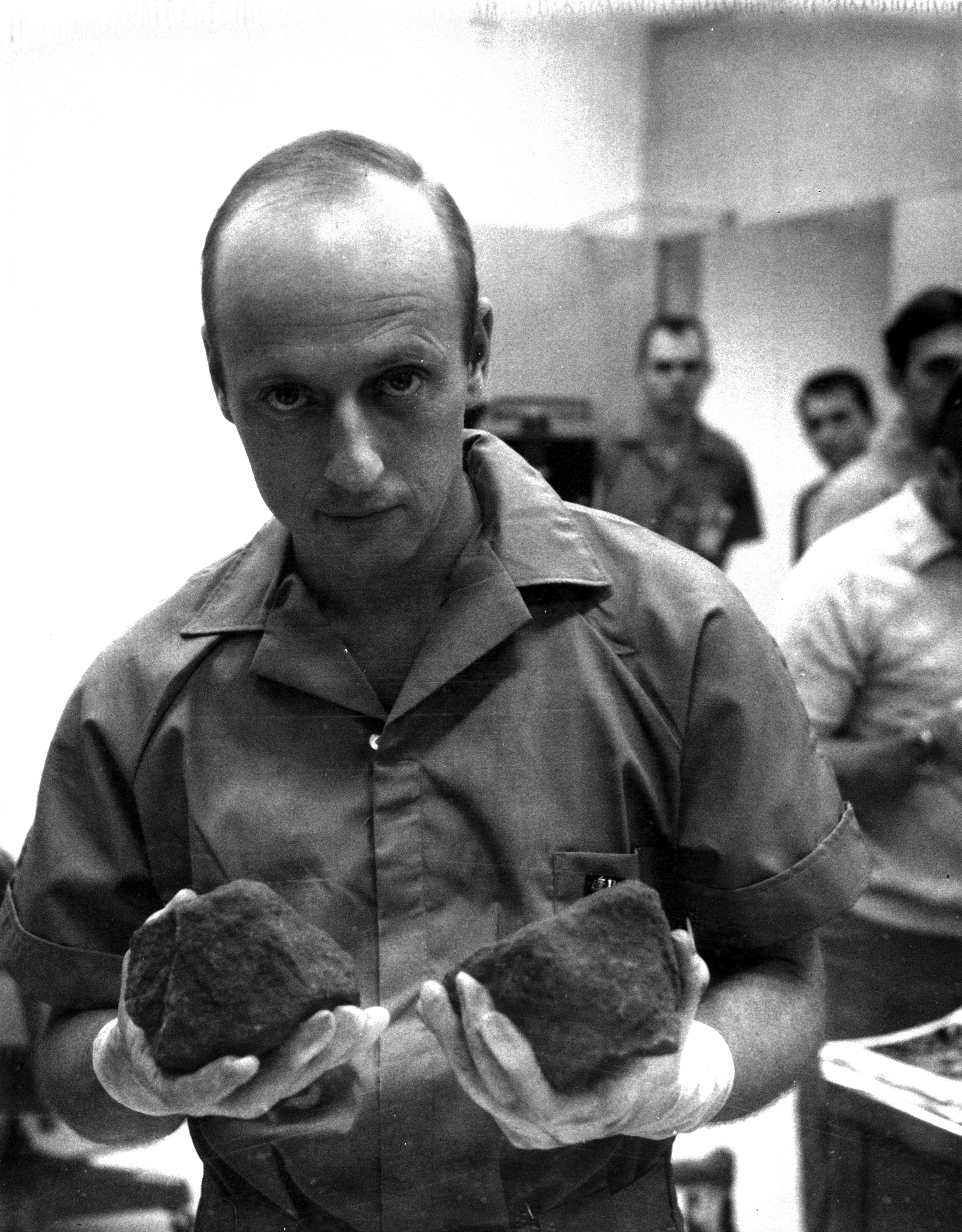

Rita Rapp with some of her space food innovations that have greatly improved the space food menu for Apollo astronauts

Rita Rapp with some of her space food innovations that have greatly improved the space food menu for Apollo astronauts

Born in 1928, Miss Rapp studied science at the University of Dayton and then took a Master’s in anatomy at the St. Louis University Graduate School of Medicine. She was one of the first women to enrol in this school. Graduating in 1953, she took a position in the Aeromedical laboratories at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, where she began assessing the effects of high g-forces on the human body, especially the blood and renal systems, using centrifuge systems.

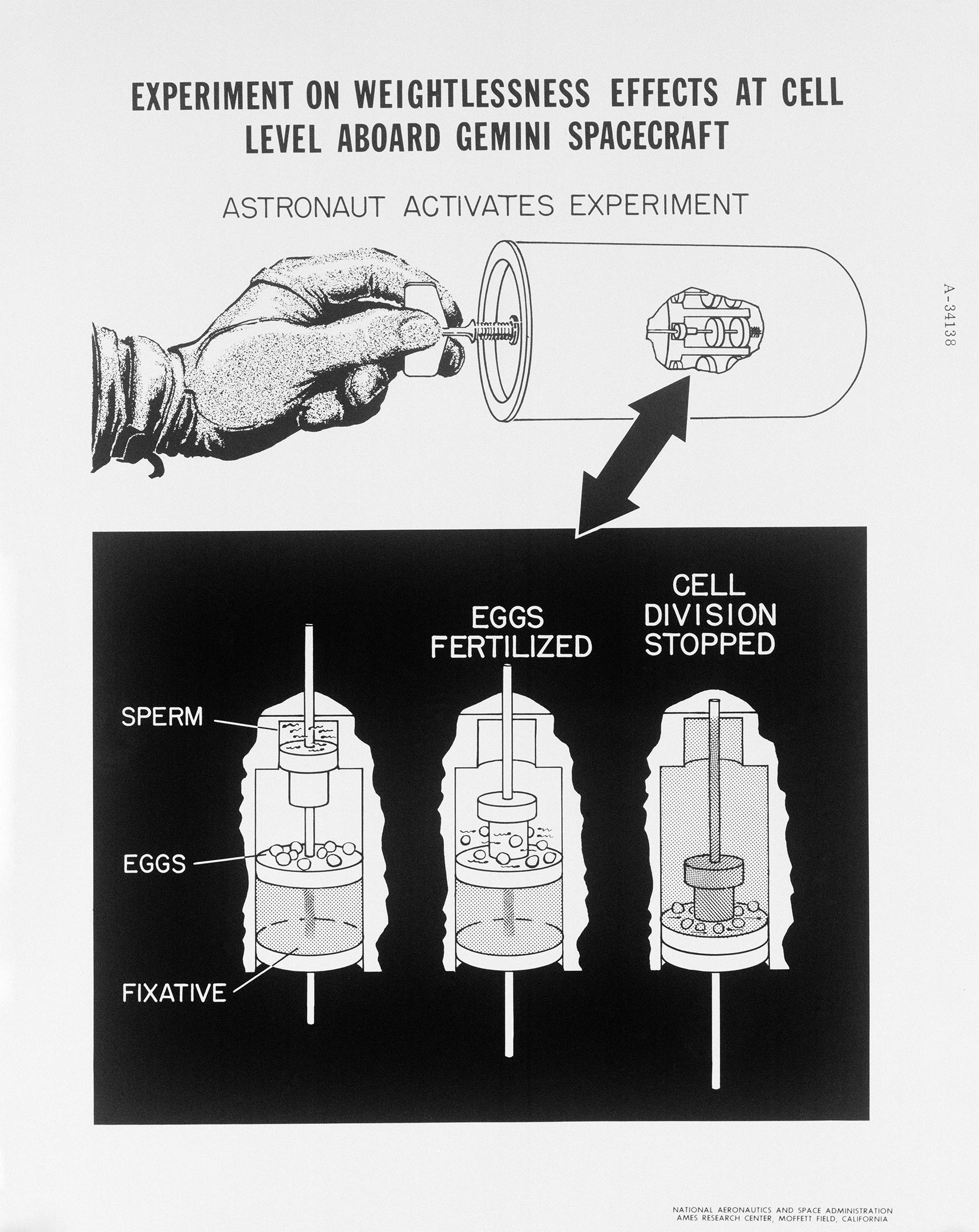

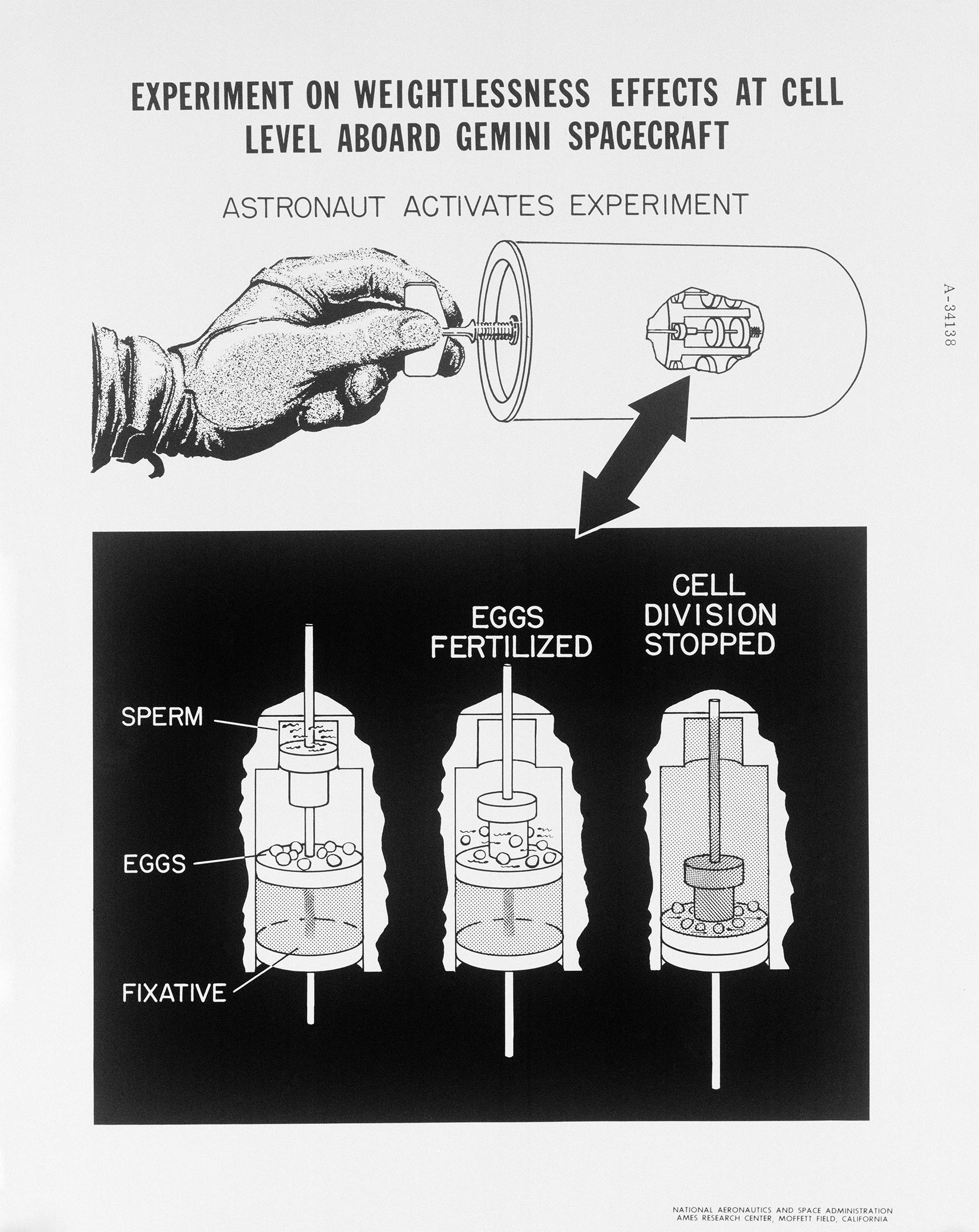

In 1960 Miss Rapp joined NASA’s Space Task Group preparing for the Mercury manned spaceflight programme, later transferring to the Manned Spacecraft Centre in Houston. For the Mercury program, she continued her work on centrifugal effects on the human body. She also designed the first elastic exercisers for Mercury and Gemini missions, devised biological experiments for the astronauts to conduct in-flight, and developed the Gemini medical kit.

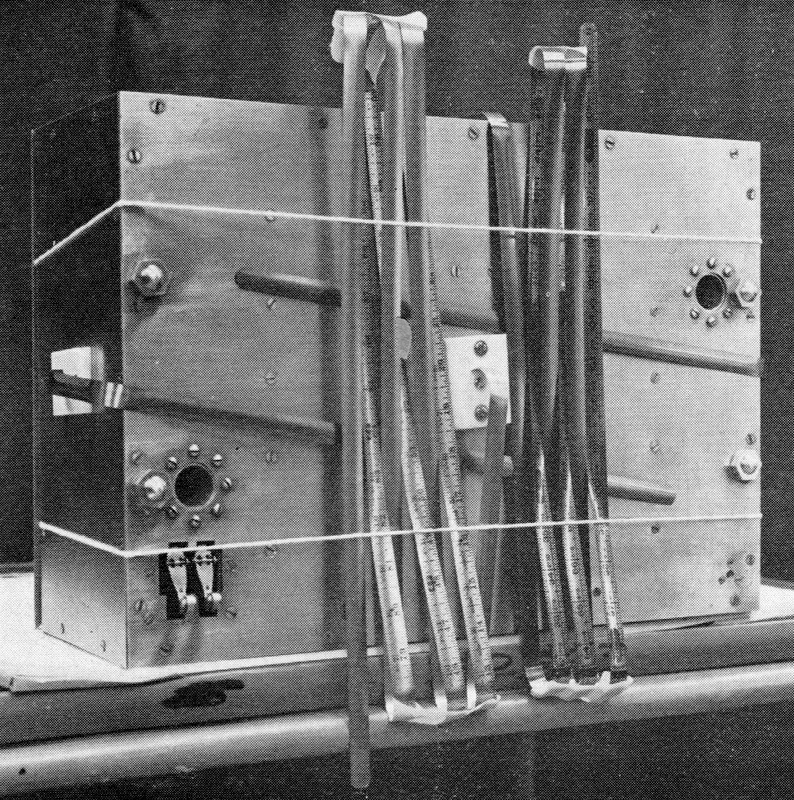

The first Gemini biological experiment, designed by Miss Rapp

The first Gemini biological experiment, designed by Miss Rapp

From Aeromedicine to Space Food

In 1966, as the Apollo programme was ramping up, Miss Rapp joined the Apollo Food Systems team. Although she has continued to work on space health and hygiene projects, in her new role her primary focus became looking at systems for storing food onboard the Apollo spacecraft. Working with dieticians, and commercial companies, she has investigated the ways space food could be packaged and prepared, and become the main interface between NASA’s Food Lab and the astronauts.

Although she tries to use as much commercially available food as possible, Miss Rapp and her team are also continually experimenting with new recipes in the food lab, gradually replacing the earlier “tubes and cubes” style of space food used in Mercury and Gemini with meals that are closer to an everyday eating experience.

She has developed improved means of food preservation, such as dehydration, thermostabilisation, irradiation and moisture control, which allows for a wider range of foods to be suitable for spaceflight, and I have no doubt these useful technologies will find their way into commercial food preparation and onto our supermarket shelves in the not-too-distant future.

Working with the Whirlpool Corporation, Miss Rapp has developed new forms of food packaging for Apollo, such as the spoon bowls, “wet packs” and cans for thermostabilised food. These containers enable astronauts to eat with more conventional utensils, instead of sucking food out of a tube or plastic bag. Creating a more natural, homelike eating experience is good for the astronauts’ morale and psychological health during missions. You can discover more about Miss Rapp's space food developments in my articles on the various Apollo missions.

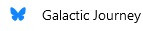

Miss Rapp takes great pride in providing the Apollo crews with the flavours and comforts of home. “I like to feed them what they like, because I want them healthy and happy,” she says. She takes note of their individual food preferences, often devises new recipes and prepares the individual meals of each Apollo astronaut separately. Her home-made sugar cookies, that she bakes herself, are a special favourite of Apollo crews, and additional supplies are included as snacks in the onboard food pantries of the Command and Lunar Modules. She also likes to provide the crews with special food “surprises”, such as the turkey dinner enjoyed by the Apollo-8 crew in lunar orbit on Christmas Eve last year.

Just the Beginning

The women of Apollo who I’ve discussed in this article are trailblazers for women’s participation in mathematics, engineering, and other technical aspects of spaceflight. While they are not the only women in professional roles in the space sector, female participation in space careers, and in science, engineering, and technology more generally, is still very low.

I hope that by highlighting the exciting Apollo-related careers of the four women above, it will plant a seed in the minds of young girls reading the Journey that they, too, can aspire to careers in scientific and technological fields that are generally thought of only as careers for men. I also hope that growing levels of female participation in the workforce, together with feminist activism, will eventually consign the sexism, discrimination and harassment that women working in all careers experience at present, to the history books—though I won’t hold my breath on it happening any time soon.

Cover of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre's in-house magazine, marking the launch of ITOS-1/TIROS-M and Australis-OSCAR-5

Cover of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre's in-house magazine, marking the launch of ITOS-1/TIROS-M and Australis-OSCAR-5 The MUAS student team with the engineering model of Australia's first amateur radio satellite

The MUAS student team with the engineering model of Australia's first amateur radio satellite Nimbus satellite image of the western half of Australia received by MUAS for the weather bureau

Nimbus satellite image of the western half of Australia received by MUAS for the weather bureau Carpenter's steel tape was used to make AO-5's flexible antennae, seen here folded in launch configuration. Notice the inch markings on the tape!

Carpenter's steel tape was used to make AO-5's flexible antennae, seen here folded in launch configuration. Notice the inch markings on the tape!

A selection of local newspaper cuttings following AO-5's launch. There was plenty of interest here in Australia.

A selection of local newspaper cuttings following AO-5's launch. There was plenty of interest here in Australia.

![[February 20, 1970] Fun-nee enough… (<i>OSCAR 5</i> and the March 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700220coverfsf-631x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1970] Both sides now (February 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700131analogcover-631x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1969] Stars above, stars at hand (January 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691220fsfcover-406x372.jpg)

![[December 6, 1969] Here comes the Sun (and Moon) — Orbiting Solar Observatory, Apollo, ESRO, and Explorer 41!](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691206oso6a-637x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1969] From the Earth to the Moon…and back (Apollo 12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691126crew-672x372.jpg)

![[November 24, 1969] The Wind That Shakes The Snottygobbles O: New Worlds December 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/NW12-cover-672x372.png)

The Clangers, I love them all

The Clangers, I love them all Cover of New Worlds for December 1969

Cover of New Worlds for December 1969 Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann One of the better collages

One of the better collages Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann Photo by Roy Cornwall

Photo by Roy Cornwall Advert for John and Yoko's Wedding Album, because I can.

Advert for John and Yoko's Wedding Album, because I can.

![[October 24, 1969] How sweet it isn't (November 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691024fsfcover-639x372.jpg)

![[October 22, 1969] Three for Three! (the flights of Soyuz 6, 7, and 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691022soyuzthree-672x372.jpg)

![[September 28, 1969] Apollo’s New Muses (Women Behind the Scenes in the Apollo Programme)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Apollo-Northcutt-Apollo-8-650x372.png)

![[August 31, 1969] Over (and under) the Moon (September 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690831analogcover-659x372.jpg)