by Gideon Marcus

There's big news on both sides of the pole regarding a pair of recently ended space flights: Apollo 13 and Soyuz 9…

Continue reading [June 20, 1970] Gemini Too (the two-week flight of Soyuz 9)

by Gideon Marcus

There's big news on both sides of the pole regarding a pair of recently ended space flights: Apollo 13 and Soyuz 9…

Continue reading [June 20, 1970] Gemini Too (the two-week flight of Soyuz 9)

by Gideon Marcus

(Un?)Lucky Seven

In 1959, NASA unveiled the identities of the first seven astronauts—the folks who would fly the Mercury capsule into space. Over the course of two years, from 1961-1963, six of them rode a pillar of flame beyond the Earth's atmosphere, one at a time.

This month, the Soviets orbited seven cosmonauts at once.

Continue reading [October 22, 1969] Three for Three! (the flights of Soyuz 6, 7, and 8)

by Gideon Marcus

Sticking close to home

The last quarter of 1968 had the newsmen on tenterhooks. After the flight of Zond 5, many suspected the Russians would try for a flight around the Moon. Would they get there before the hastily rescheduled Apollo 8?

They did not, and now it seems they are taking a different tack, trying to progress in endeavors closer to home. On January 14, the Soviets launched Soyuz 4 into orbit carrying a single cosmonaut, Vladimir Shatalov. This was ho hum stuff—the putatively multi-man Soyuz was once again carrying a single occupant. Ah, but on the 16th, Soyuz 5 took off with cosmonauts Boris Volnyov, Aleksey Yeliseyev, and Evegenii Khrunov, the first three-seat flight since Voskhod 1, four years ago.

More than that, the two craft docked in orbit, the first time two piloted craft have managed the feat. Then Yeliseyev and Khrunov donned space suits, opened their hatch, and walked next door. They weren't visiting for a cup of borscht; they were there to stay, and they bore gifts: newspapers and letters from after Shatalov had taken off! The next day, Soyuz 4 landed with the two new passengers. As of this article's going to press, Volnyov should have landed his Soyuz 5—safely, I trust.

The Soviets are already beging to hail the mission as the construction of the first station in space, and there's no doubt that a lot of firsts have been scored. On the other hand, the two Soyuz craft were only linked for a few hours, and there was no easy way to get between the two craft. Really, they haven't done anything that couldn't have been done during our Gemini program.

That said, this may only be the beginning. Unlike Voskhod, which only comprised a couple of flights, there have been a number of Soyuz missions, both manned and unmanned, so it's probably only a matter of time before a truly ambitious trek is managed, perhaps a real space station.

What's more impressive? American boots on the Moon, or a permanent Soviet presence in near Earth orbit? You be the judge.

Mail's in!

The latest issue of F&SF offers a myriad of treats that are, in some ways, as exciting as today's space news. Let's dive in:

Another splurty cover by Russell FitzGerald

Attitudes, by James H. Schmitz

Azard is one of the Malatlo, the group of peaceniks who have divorced themselves from the Federation of the Hub. Years ago, the Malatlo were given their own planet, far away, but next door to the Raceels, an up-and-coming race, so that the separatists might not be too lonely.

Now war has destroyed both worlds, and Azard is being escorted by three representatives of the Federation to a new world. It's a magnanimous mission…so why is Azard contemplating the murder of his benefactors? And is all really what it seems?

I found the telling of the story a bit talky and stilted, and yet, when I was done, I found the thing stuck with me, some of the scenes vivid in the extreme. So, four stars for a fine opening piece.

by Gahan Wilson

The Cave, by Yevgeny Zamyatin

Per Sam Moskowitz' introduction, this is the tale of the end result of Communism as envisioned by a dissident writer in 1920 Leningrad. As winter sets in, an impoverished citizen in the "equal" society wrestles with the urge to steal wood from an advantaged neighbor. Soviet Marxism thus results in reversion to Stone Age sensibilities.

An interesting curiosity. Three stars.

Nightwalker, by Larry Brody

Frank Whalen is a super-spy with a secret: his body shoots off electricity at will. He also has a super suit, which confers stealth, but also has the annoying side effect of causing an all-over itch. This tale rather straightforwardly details an adventure Whalen has behind the Bamboo Curtain, and how he escapes from a Red Chinese jail.

Probably the first in an ongoing series, there's not really enough of Whalen yet to hang on to, character-wise. If you like superhero comics, you'll probably enjoy this one, in a superficial sort of way.

Three stars.

Dormant Soul, by Josephine Saxton

Saxton is an English author whose work generally fails to resonate with me, but this time, she channels her inner Pam Zoline with this beautiful, stream-of-consicousness story. It deals with a prematurely old widow struggling with inexplicable migraines, deep depression, and an uncaring medical system that seems tailor-made to perpetuate the problem with useless nostrums and a callous ear.

The solution? Wine and a bit of angelic help.

It's a beautiful, moving piece, and it was well on its way to five stars before the typically British, bummer ending. Still four stars.

Drool, by Vance Aandahl

Justice Stewart once observed (essentially) "I can't tell you what pornography is, but I know it when I see it." Aandahl proves that, "when correctly viewed, everything is lewd" (thank you Tom Lehrer) in this effective vignette.

Four stars.

Twin Sisters, by Doris Pitkin Buck

A short poem personifying the rain. I liked it. Four stars.

Pater One Pater Two, by Patrick Meadows

Two 21st Century disasters combine to doom the 24th Century: a doomsday weapon renders all of the Earth uninhabitable save for Greece and Asia Minor, and a birth control initiative backed by technology has gone awry, preventing all new births. It's up to Jacson and Marya from the island of Xios to topple the remnants of the past to save the future.

An interesting, innovative tale. Four stars.

Uncertain, Coy, and Hard to Please, by Isaac Asimov

For this piece, I felt it was important to have a female perspective—you'll understand why…

by Janice L. Newman

Asimov’s most recent “Science” article is on feminism. He never uses the word, but feminism is what it argues: that men and women are inherently equal, and that it is only cultural and artificial distinctions that keep them from being equal. It’s an excellent screed. For many women it would be a revelation, particularly if they have had no prior contact with feminist ideas.

Some might take exception to the description of the male/female relationship as slavemaster/slave, but I do not. For too long women have been considered property, unable to own anything: not money, not land, not their own work and discoveries, not even their own bodies. Even today a woman cannot open a checking account at the vast majority of banks without her husband’s or father’s signature. Consider how crippling this is for an independent person in modern society.

I can’t agree with every argument Asimov makes. While I concede that courtly love is an artificial construct, one need only look to the animal kingdom to find plenty of animals that mate for life, and which become despondent if one of the pair is removed. Nor can I dismiss fatherly love as purely cultural. Children look like their parents, after all, and men who cared for partners and offspring were more likely to have children that made it to adulthood.

However, these are minor quibbles. Overall the piece is well thought-out and logical and usually right, and I believe it should be required reading for all fen…indeed, all persons.

Including its author.

Asimov is well-known for groping women at conventions: grabbing their backsides or their frontsides, even seizing and kissing women who had approached him in the hope of getting an autograph. I am certain that he thinks such behavior is flattering–indeed, he lists the "smirk and the leer" as among the petty rewards of being a woman in today's society. I cannot speak for all women; likely some did feel flattered by such attentions. But having talked with some of his victims, I know that this was not so in many cases.

I have never met Asimov in person. Perhaps friends have deliberately kept me away from him at conventions to protect me. At this point, it seems increasingly unlikely that I will ever meet him. But if I ever do, I would like to say to him, “You, too, wield the power of the slavemaster. The very ‘silliness’ that you decry as an artificial defense mechanism is exactly what is coming into play when you kiss a woman and she blushes and laughs awkwardly. Hers is a conditioned response born, at its heart, out of fear.”

Perhaps it is not surprising that Asimov apparently can’t make the extra leap to apply his reasoning to his own behavior. As excellent and revelatory as this piece is, it seems to come entirely from Asimov’s mind without any discussion with actual women. In fact, it’s unlikely that he’s had much opportunity to see things from a ‘feminine perspective’, considering the vast majority of media is from a male point of view. Not surprising, but it is saddening and frustrating.

I don’t know if I could convince him that he is not exempt, that however unthreatening he may think himself, society nonetheless places the slavemaster’s whip firmly in his hand. But perhaps, someday, he can: I think the man capable of writing such an important feminist piece could learn from his own words.

Five stars.

by Gideon Marcus

After All the Dreaming Ends, by Gary Jennings

A simple boy meets girl episode in wartime, just before the boy is to ship off to the European Theater of Operations. Except the girl isn't there—she's dying in a hospital bed 25 years later. To sleep, perchance to dream…and what a beautiful, romantic dream.

A sweet, wistful piece. I'm a sucker for love stories. Five stars.

A pleasant recounting

Well now—not a clunker in the bunch, and some Star material to boot. Indeed, this is the first 4-star issue of F&SF in the history of our reviewing the magazine! That's exciting news in the skies above and on the ground, and definitely enough to keep us renewing our subscription—to F&SF AND Aviation Weekly.

This is reported to be the official Soyuz-3 mission patch. It was apparently intended to be worn by Cosmonaut Beregovoi or at least flown during the mission, however it ia not clear if it was actually used

This is reported to be the official Soyuz-3 mission patch. It was apparently intended to be worn by Cosmonaut Beregovoi or at least flown during the mission, however it ia not clear if it was actually used New Cosmonaut, New Spacecraft

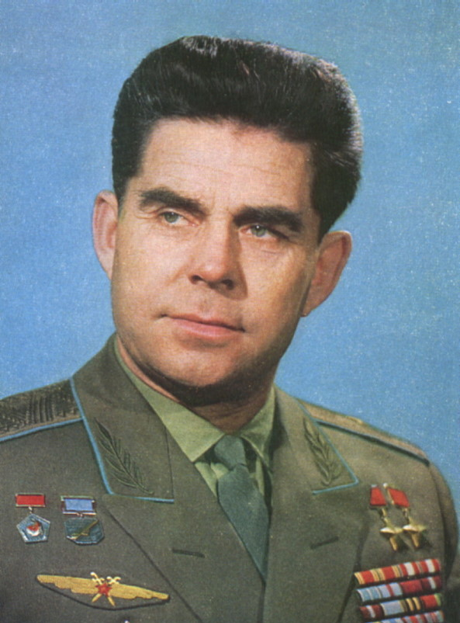

New Cosmonaut, New Spacecraft Although not previously known to be a member of the Soviet cosmonaut team, Col. Beregovoi is a distinguished World War Two veteran, who was awarded the decoration of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1944. After the war he became a test pilot and is said to have joined the cosmonaut team in 1964. At 47, Beregovoi now becomes the oldest person to make a spaceflight, taking the record away from 45-year-old Apollo-7 commander Capt. Wally Schirra only weeks after he achieved it.

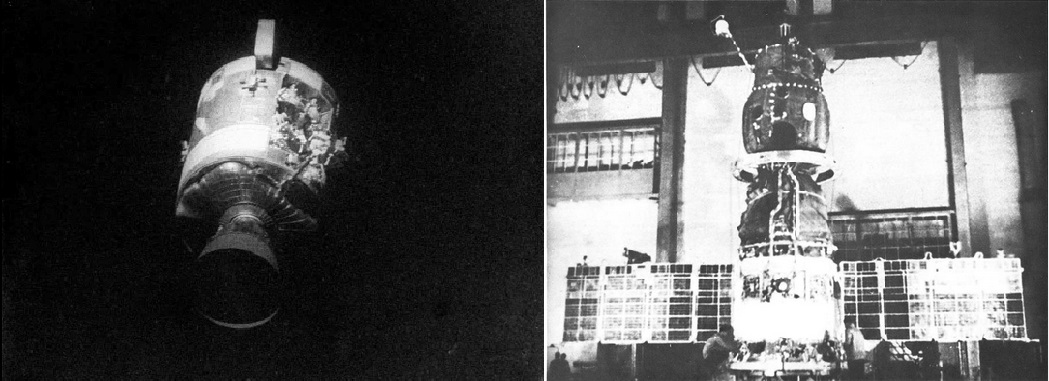

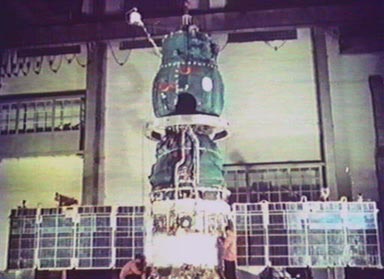

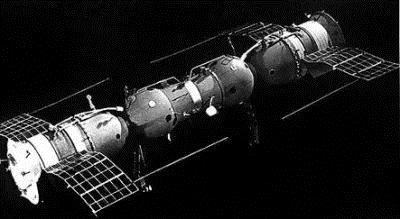

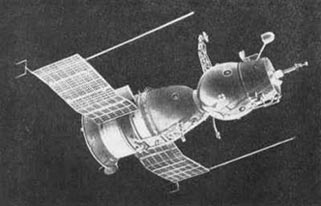

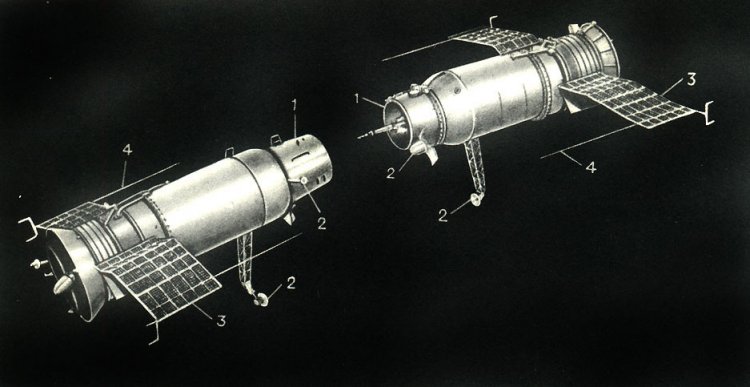

Although not previously known to be a member of the Soviet cosmonaut team, Col. Beregovoi is a distinguished World War Two veteran, who was awarded the decoration of Hero of the Soviet Union in 1944. After the war he became a test pilot and is said to have joined the cosmonaut team in 1964. At 47, Beregovoi now becomes the oldest person to make a spaceflight, taking the record away from 45-year-old Apollo-7 commander Capt. Wally Schirra only weeks after he achieved it. The few images of the Soyuz spacecraft available indicate that, unlike the Apollo Command Service Module, it has three sections: a ‘service module’ containing life-support and propulsion systems; and two other modules – one roughly bell-shaped and the other, attached to it, spherical – which both seem to be crew accommodation, given that press releases from the TASS newsagency have described the spacecraft as “two-roomed”.

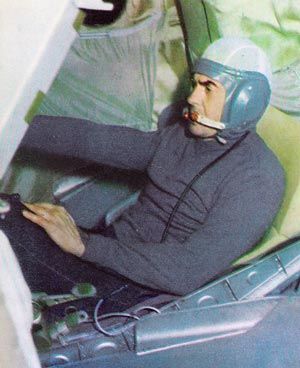

The few images of the Soyuz spacecraft available indicate that, unlike the Apollo Command Service Module, it has three sections: a ‘service module’ containing life-support and propulsion systems; and two other modules – one roughly bell-shaped and the other, attached to it, spherical – which both seem to be crew accommodation, given that press releases from the TASS newsagency have described the spacecraft as “two-roomed”.  Colonel Beregovoi during his training at Star City

Colonel Beregovoi during his training at Star City Cosmonaut Beregovoi on the launchpad, apparently alone

Cosmonaut Beregovoi on the launchpad, apparently alone Was an actual docking between Soyuz-2 and 3 planned, in addition to the rendezvous manoeuvres, with one or two additional crew members from Soyuz-3 transferring to the automated craft to return from orbit? Did the Soviets keep the presence of additional cosmonauts on Soyuz-3 secret to save face in the event that such a docking and crew transfer failed? Even if Beregovoi was alone in Soyuz-3, was it planned for him to dock with Soyuz-2 to demonstrate that a pilot could accomplish a manual docking, similar to the capabilities demonstrated by the crew of Apollo-7? TASS press releases about the mission were ambiguously worded and extremely light on detail, so – as usual with the Soviet space programme – it may be a very long time before we have answers to these questions.

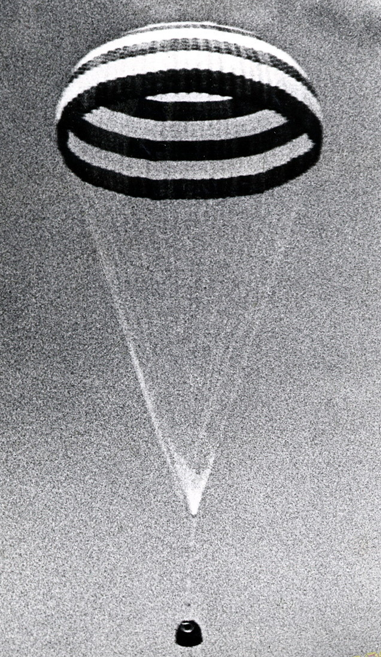

Was an actual docking between Soyuz-2 and 3 planned, in addition to the rendezvous manoeuvres, with one or two additional crew members from Soyuz-3 transferring to the automated craft to return from orbit? Did the Soviets keep the presence of additional cosmonauts on Soyuz-3 secret to save face in the event that such a docking and crew transfer failed? Even if Beregovoi was alone in Soyuz-3, was it planned for him to dock with Soyuz-2 to demonstrate that a pilot could accomplish a manual docking, similar to the capabilities demonstrated by the crew of Apollo-7? TASS press releases about the mission were ambiguously worded and extremely light on detail, so – as usual with the Soviet space programme – it may be a very long time before we have answers to these questions. Soyuz-2 was remotely commanded to return to Earth after just three days. In what was presumably another demonstration of the Soyuz spacecraft’s redesigned landing system, TASS reported that the spacecraft’s re-entry was slowed by parachutes and cushioned “with the use of a soft-landing system at the last stage”.

Soyuz-2 was remotely commanded to return to Earth after just three days. In what was presumably another demonstration of the Soyuz spacecraft’s redesigned landing system, TASS reported that the spacecraft’s re-entry was slowed by parachutes and cushioned “with the use of a soft-landing system at the last stage”. A still from the three-minute brodcast from Soyuz-3 showing Colonel Beregovoi

A still from the three-minute brodcast from Soyuz-3 showing Colonel Beregovoi

Following his safe return, Col. Beregovoi was flown to Moscow, where he received a red-carpet welcome, an instant promotion to Major-General and the award of the Order of Lenin. At the ceremony, the Soviet party leader, Mr Brezhnev, devoted most of his 15-minute speech to praise of the Soviet manned space programme, describing Soyuz-3 as a “complete success”. He said that the mission had brought nearer the day when “Man will not be the guest but the host of space”. He also offered a word of praise to the Apollo-7 astronauts, referring to them as “courageous”.

Following his safe return, Col. Beregovoi was flown to Moscow, where he received a red-carpet welcome, an instant promotion to Major-General and the award of the Order of Lenin. At the ceremony, the Soviet party leader, Mr Brezhnev, devoted most of his 15-minute speech to praise of the Soviet manned space programme, describing Soyuz-3 as a “complete success”. He said that the mission had brought nearer the day when “Man will not be the guest but the host of space”. He also offered a word of praise to the Apollo-7 astronauts, referring to them as “courageous”.  Prof. Sedov on an earlier visit to the United States in 1961 at the time of the USSR's first manned spaceflight

Prof. Sedov on an earlier visit to the United States in 1961 at the time of the USSR's first manned spaceflight Left: Former NASA Administrator James Webb speaking at the Apollo-7 awards event, at which he also received NASA's highest award. Right: After the formal ceremony, President Johnson

(second from left) chats with Apollo 7 astronauts Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham.

Left: Former NASA Administrator James Webb speaking at the Apollo-7 awards event, at which he also received NASA's highest award. Right: After the formal ceremony, President Johnson

(second from left) chats with Apollo 7 astronauts Schirra, Eisele and Cunningham.

by Gideon Marcus

Up and over

Just as America returned to space in a big way with this month's flight of Apollo 7, the Soviets have also recovered from their 1967 tragedy (Soyuz 1) with an impressive feat. Georgy Beregovoi, a rookie cosmonaut (ironically also the oldest man in space thus far, surpassing 45 year-old Wally Schirra by two years) has taken Soyuz 3 into orbit for a series of rendezvous and perhaps dockings (TASS is being vague on the issue) with the unmanned Soyuz 2.

Comrade Beregovoi in training

We've seen flights like this before, but this is the first time there has been a person involved. Many are calling this a harbinger of an impending lunar flight, though NASA is adamant that this particular flight won't go to the moon. Indeed, Dr. Ed Welsh, Secretary of the National Aeronautics and Space Council says Soyuz and September's Zond 5, which went around the moon, are completely different craft and the Russians aren't even close to fielding a lunar mission.

We'll have more on this flight in a few days. Stay tuned.

On the ground

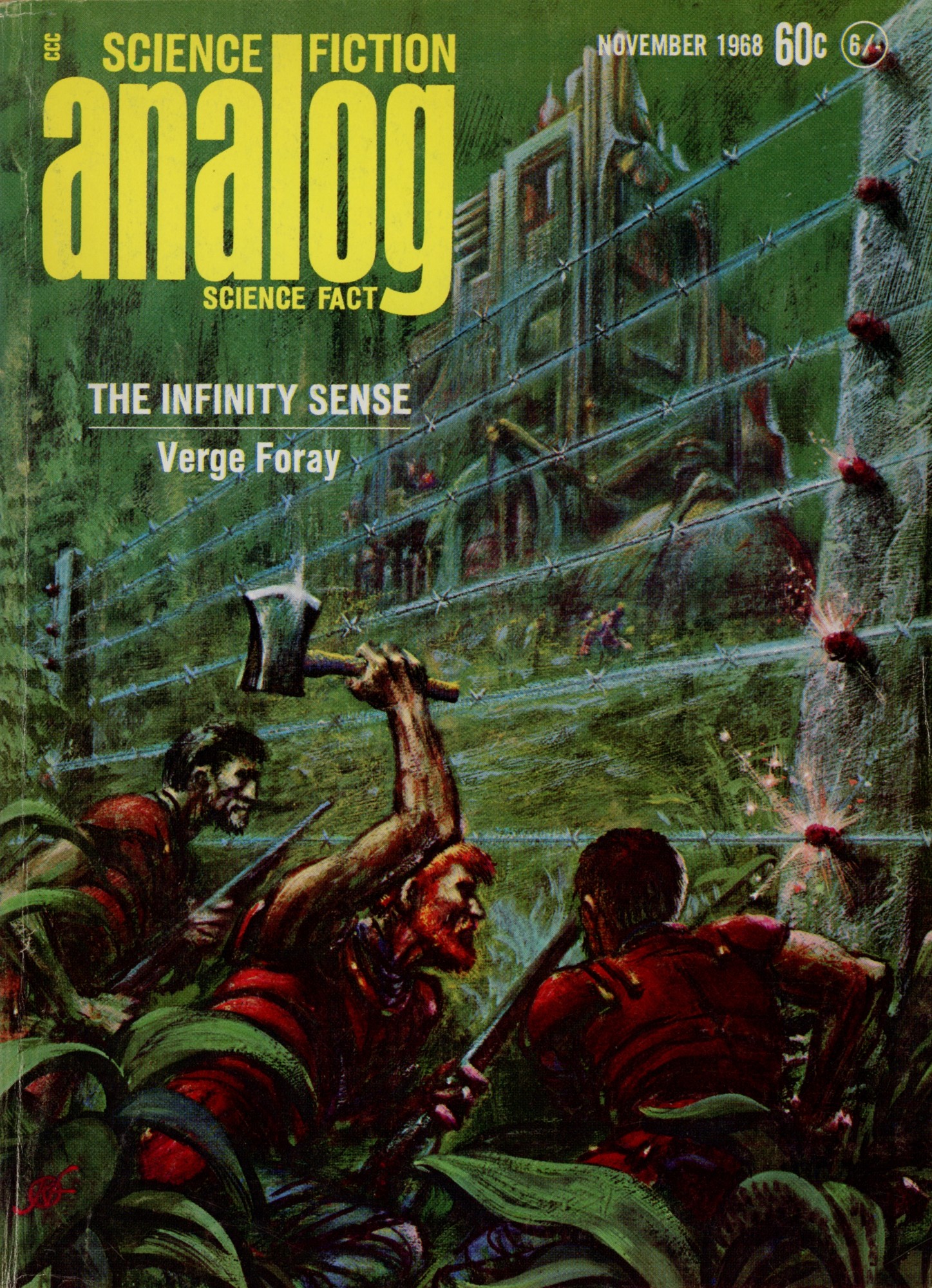

Like the flights of Soyuz 2 and 3, this month's Analog is outwardly impressive, but once you dig in, it's not so great.

by Kelly Freas

The Infinity Sense, by Verge Foray

by Kelly Freas

Centuries from now, after the fall of the Age of Science, humanity is divided into two camps: the "Olsaparns", who dwell in isolated technological camps and retain a semblance of the original technology and society, and the Novos—psionically adept savages who live in conservative Packs. One of the Pack members is Starn, who possesses a brand new ability that allows him to best even the telepathically and premonitionally blessed. He runs afoul of Nagister Nont, a highly adept, highly disagreeable trader, who kidnaps his wife.

After a raid on the Olsaparns leaves Starn close to death, the technologists remake him into something more machine than man, like Ted White's Android Avenger. The Olsaparns want Nont out of the picture, so they help Starn in his quest to defeat the mutant and get back his wife.

I have no fault with the writing, which is brisk and engaging. I take some issue with the pages of discussion on whether or not psi powers be linked with primitiveness, or the concept that humanity could regress to Pithecanthropy in a scant few generations (or the idea that evolution must be a road that one goes forward and backward on; I thought we gave up teleology last century). But I blazed through the novella in short order, so… four stars.

The Ultimate Danger, by W. Macfarlane

by Kelly Freas

In which Captain Lew Frizel takes a shipload of eggheads to a hallucinogenic planet. He is the only one who, more or less, keeps his head. The message appears to be that LSD can be employed by aliens to judge our character. Or something.

Three stars?

The Shots Felt 'Round the World, by Edward C. Walterscheid

This piece, on atomic tests, was much easier reading than Walterscheid's last article. Do you realize that we have detonated half a billion TNT tons worth of nuclear explosives since 1945? It's a wonder there's anything left of Nevada.

Four stars.

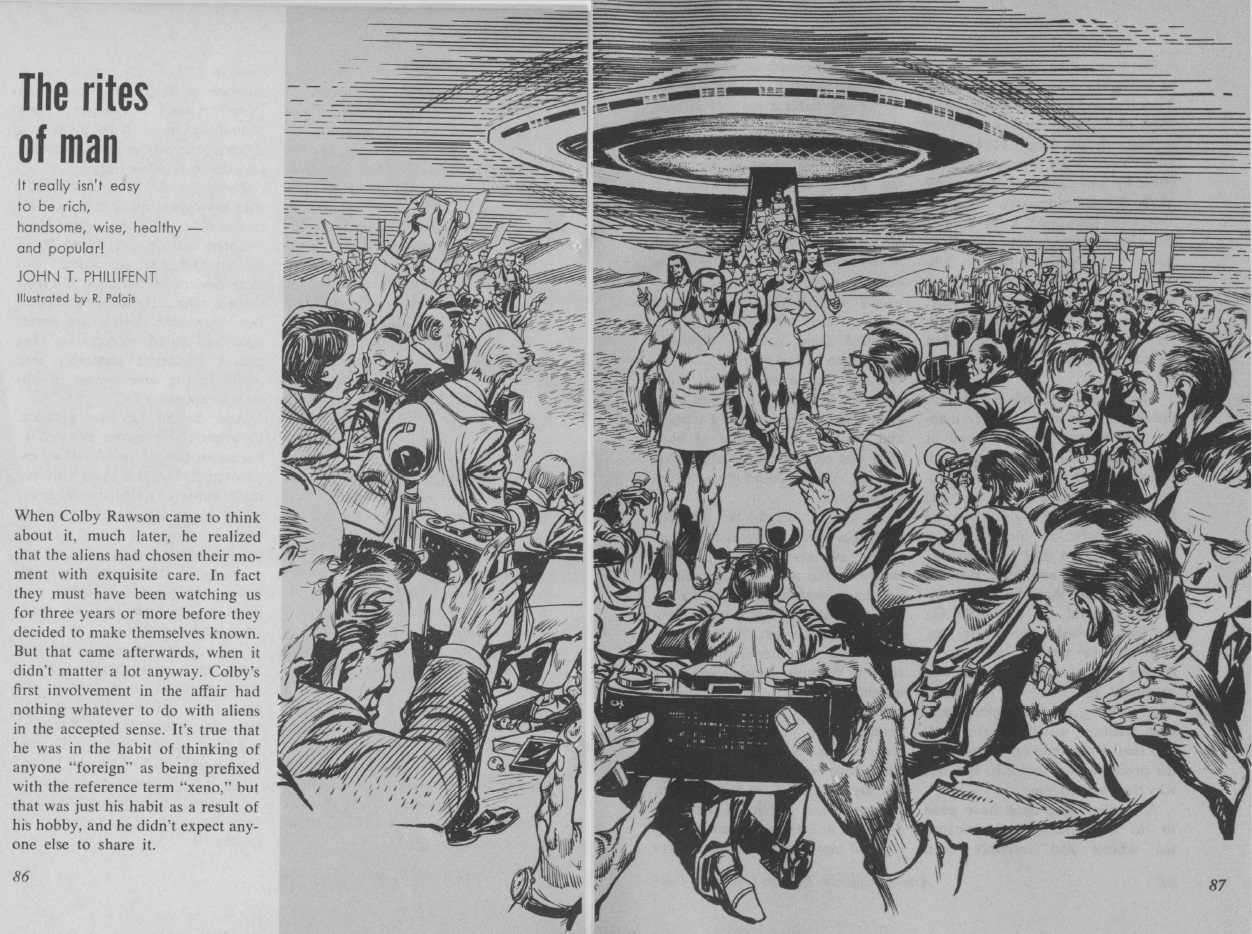

The Rites of Man, by John T. Phillifent

by Rudolph Palais

A scientist is working on rationalizing the art of interpersonal relations (because in Phillifent's universe, no one has invented sociology). About twenty pages into that effort, humanoid (really, human) aliens show up and ask to be allowed to compete in the Olympics. They do, but they lose on purpose so we won't hate them. Then we interbreed.

Possibly the dullest, most pointless story I've ever read in this magazine. One star.

The Alien Enemy, by Michael Karageorge

by Leo Summers

Humanity is a resilient creature, tough enough to tame any world. Except that planet Sibylla, with its poisonous soil, extreme axial tilt, thin atmosphere, temperature extremes, high gravity, and violent weather may actually be more than Terrans can handle. What does one do when a world is too minimal to sustain a colony? And what is the value of 10,000 settler lives against the teeming, impoverished billions of Earth?

This is a vividly written piece with some excellent astronomy. If I didn't know better, I'd say Poul Anderson is writing under a pseudonym. I felt the solution to the colonists' problem, though reasonable, was not sufficiently set up to be deduced. Also, I felt Karageorge missed the opportunity to make a more profound statement at the end than "well, humanity can lick almost all comers." I'd have preferred something on the point of colonization or the shifting of priorities on a racial scale.

Still, a high three stars.

Split Personality, by Jack Wodhams

by Kelly Freas

Mauger, a homicidal brute, agrees to be split in two for science instead of getting the chair. Instead of this resulting in two new individuals, it turns out that the two halves remain connected, the gestalt whole. Thus, Maugam can literally be in two places at once.

This is timely as the first interstellar drive has had teething troubles. Two test ships have gotten lost, unable to communicate with Earth. Now, half of Maugam can fly on the ship while the other stays home and reports, since telepathy, for some reason, is instant.

It's actually not a bad story, though it's really just a bunch of magic and coincidence. It works because Wodhams has set it up to work a certain way, not because this is any kind of realistic scientific extrapolation. Also, it's hard to work up any sympathy for a homicidal brute.

Three stars.

Doing the math

When everything is crunched together, we end up with Analog clocking in at exactly 3 stars—again, adequate, but vaguely disappointing. On the other hand, it's been something of a banner month in SF (provided you're not looking for female writers; they wrote less than 7% of the new fiction pieces published). Except for IF (2.6), every other outlet scored higher than 3. To wit:

New Worlds (3.1), Amazing (3.2), New Writings 13 (3.3), Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.4), and Galaxy (3.9).

The stuff worth reading (4/5 stars) would fill a whopping three magazines. Who says the science fiction magazine age is over?

by Kaye Dee

As I noted in my previous article, October was such a busy month for space activity that I had to hold over several items for this month. But November has already provided us with plenty of space news as well. Even though both American and Soviet manned spaceflight is currently on hold while the investigations into their respective accidents continue, preparations for putting astronauts and cosmonauts on the Moon are ongoing and the Moon race is still on!

“Oh, it’s terrific, the building’s shaking!”

Opening the door to human lunar exploration needs an immensely powerful booster, and the successful launch of Apollo-4 a few days ago on 9 November has demonstrated that NASA has a rocket that is up to the task. Although the Saturn 1B rocket intended to loft Apollo Earth-orbiting missions has already been tested, Apollo-4 (also designated SA-501) marked the first flight of a complete Saturn V lunar launcher.

The sheer power of the massive rocket took everyone by surprise. When Apollo-4 took off from Pad 39A at the John F. Kennedy Space Centre, the sound pressure waves it generated rattled the new Launch Control Centre, three miles from the launch pad, causing dust to fall from the ceiling onto the launch controllers’ consoles. At the nearby Press Centre, ceiling tiles fell from the roof. Reporting live from the site, Walter Cronkite described the experience: “… our building’s shaking here. Our building’s shaking! Oh, it’s terrific, the building’s shaking! This big blast window is shaking! We’re holding it with our hands! Look at that rocket go into the clouds at 3000 feet! … You can see it… you can see it… oh the roar is terrific!”

Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Centre at Kennedy Space Centre, under construction in early 1966. The Apollo-4 launch was controlled from here

Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Centre at Kennedy Space Centre, under construction in early 1966. The Apollo-4 launch was controlled from here

Could it be that the sound of a Saturn V launch is one of the loudest noises, natural or artificial, ever heard by human beings? (Apart, perhaps, from the explosion of an atomic bomb?) I hope I’ll get the opportunity to hear, and see, a Saturn V launch for myself at some point in the future.

The Power for the Glory

Developed by Dr. Wernher von Braun’s team at NASA’s George C. Marshall Space Flight Centre, everything about the Saturn V is impressive. The 363-foot vehicle weighs 3,000-tons and the thrust of its first-stage motors alone is 71 million pounds! No wonder it rattled buildings miles away at liftoff!

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The launcher consists of three stages. The Boeing-built S1-C first stage, when fully fuelled with RP-1 kerosene and liquid oxygen, has a total mass of 4,881,000 pounds. Its five F-1 engines are arranged so that the four outer engines are gimballed, enabling them to turn so they can steer the rocket, while the fifth is fixed in position in the centre. Constructed by North American Aviation and weighing 1,060,000 pounds, the S-II second stage has five Rocketdyne-built cryogenic J-2 engines, powered by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. They are arranged in a similar manner to the first stage engines, and also used for steering. The Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage has been built by the Douglas Aircraft Company and has a single J-2 engine using the same cryogenic fuel as the second stage. Fully fuelled, it weighs approximately 262,000 pounds. Guidance and telemetry systems for the rocket are contained within an instrument unit located on top of the third stage.

Soaring into the Future

This first Saturn V test flight has been tremendously important to the ultimate success of the Apollo programme, marking several necessary first steps: the first launch from Complex 39 at Cape Kennedy, built especially for Apollo; the first flight of the complete Apollo/Saturn V space vehicle; and the first test of Apollo Command Module’s performance re-entering the Earth's atmosphere at a velocity approximating that expected when returning from a lunar mission. In addition, the flight enabled testing of many modifications made to the Command Module in the wake of the January fire. This included the functioning of the thermal seals used in the new quick-release spacecraft hatch design.

Up, Up and Away!

Apollo-4 lifted off on schedule at 7am US Eastern time. Just 12 minutes later it successfully placed a Command and Service Module (CSM), weighing a record 278,885 pounds, into orbit 115 miles above the Earth. This is equivalent to the parking orbit that will be used during lunar missions to check out the spacecraft before it embarks for the Moon.

After two orbits, the third stage engine was re-ignited (itself another space first) to simulate the trans-lunar injection burn that will be used to send Apollo missions on their way to the Moon. This sent the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit with an apogee of 10,700 miles. Shortly afterwards, the CSM separated from the S-IVB stage and, after passing apogee, the Service Module engine was fired for 281 seconds to increase the re-entry speed to 36,639 feet per second, bringing the CSM into conditions simulating a return from the Moon.

An image of the Earth taken from an automatic camera on the Apollo-4 Command Module

After a successful re-entry, the Command Module splashed down approximately 10 miles from its target landing site in the North Pacific Ocean and was recovered by the aircraft carrier USS Bennington. The mission lasted just eight hours 36 minutes and 54 seconds (four minutes six seconds ahead of schedule!), but it successfully demonstrated all the major components of an Apollo mission, apart from the Lunar Module (which is still in development) that will make the actual landing on the Moon’s surface. In a special message of congratulations to the NASA team, President Johnson said the flight “symbolises the power this nation is harnessing for the peaceful exploration of space”.

Goodbye Lunar Orbiters…

While Apollo’s chariot was readied for its first test flight, NASA has continued its unmanned exploration of the Moon, to ensure a safe landing for the astronauts. In August, Gideon gave us an excellent summary of NASA’s Lunar Orbiter programme, the first three missions of which were designed to study potential Apollo landing sites. Lunar Orbiter-3, launched back in February this year, met its fate last month when the spacecraft was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface on 9 October. Despite the failure of its imaging system in March, Lunar Orbiter-3 was tracked from Earth for several months for lunar geodesy research and communication experiments. On 30 August, commands were sent to the spacecraft to circularise its orbit to 99 miles in order to simulate an Apollo trajectory.

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Each Lunar Orbiter mission has been de-orbited so that it will not become a navigation hazard to future manned Apollo spacecraft. Consequently, before its manoeuvring thrusters were depleted, Lunar Orbiter 3 was commanded on 9 October to impact on the Moon, hitting the lunar surface at 14 degrees 36 minutes North latitude and 91 degrees 42 minutes West longitude. Co-incidentally, Lunar Orbiter-4, which failed back in July and could not be controlled, decayed naturally from orbit and impacted on the Moon on 6 October. Lunar Orbiter-5, launched in August, remains in orbit.

…Hello Surveyor 6

A month after the demise of the Lunar Orbiters, NASA’s Surveyor-6 probe has made a much softer landing on the lunar surface, achieving a “spot on” touchdown in the rugged Sinus Medii (Central Bay – it’s in the centre of the Moon's visible hemisphere) on 10 November (Australian time; 9 November in the US). This region is a potential site for the first Apollo landing, but since it appeared to be cratered and rocky, mission planners needed to know if its geological structure (different to the ‘plains’ areas where earlier Surveyor missions have landed) could support the weight of a manned Lunar Module.

Only an hour after landing safely, Surveyor-6 was operational and sent back pictures of a lunar cliff about a mile from its landing point, which has been described as “the most rugged feature we have yet seen on the Moon”. The first panoramas from Surveyor indicate that the landing site is not as rough as anticipated, and seems suitable for an Apollo landing.

Deep Space Network stations in Australia are helping to support the Surveyor-6 mission, as well as Surveyor-5, that landed in the Mare Tranquilitatis (Sea of Tranquillity) in September and is still operational. Hopefully both spacecraft will survive the next lunar night, commencing two weeks from now. NASA plans to send one more Surveyor probe to the Moon, in January, so look out for a review of the completed Surveyor programme early next year.

Watching the Sun for Astronaut Safety

With the Sun moving towards its maximum activity late next year or early in 1969, and likely to still be very active when the Apollo landing missions are occurring (assuming that the programme resumes some time within the next 12 months), NASA has wasted no time in launching another spacecraft in its Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO) series, to help characterise the effects of solar activity in deep space. A NASA spokesman was recently quoted as saying that “A study of solar activity and its effect on Earth, aside from basic scientific interest, is necessary for a greater understanding of the space environment prior to manned flights to the Moon”.

OSO-4 under construction

OSO-4 under construction

Launched on 18 October, OSO-4 (also known as OSO-D) is the latest satellite developed under the leadership of Dr. Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first female executive, who is Chief of Astronomy and Solar Physics. The satellite is equipped to measure the direction and intensity of Ultraviolet, X-ray and Gamma radiation, not just from the Sun, but across the entire celestial sphere.

The OSO-4 spacecraft, like its predecessors, consists of a solar-cell covered “sail” section and a “wheel” section that spins about an axis perpendicular to the pointing direction of the sail. The sail carries a 75 pound payload of two instruments that are kept pointing on the centre of the Sun. The wheel carries a 100 pound payload of seven instruments and rotates once every two seconds. This rotation enables the instruments to scan the solar disc and atmosphere as well as other parts of the galaxy. The satellite’s extended arms give it greater axial stability.

Hopefully, OSO-4 will have a long lifespan, producing data as solar activity increases across the Sun’s cycle, and enhancing safety for the Apollo and Soviet crews who will venture beyond the protection of the van Allen belts on their way to the Moon.

What are the Soviets Up To?

The USSR has been remarkably quiet about its manned lunar programme. One could almost think that they had given up racing Apollo to the Moon, if not for the rumours and hints that constantly swirl around. Rumours abounded at the time of the tragically lost Soyuz-1 mission that it was intended to be a space spectacular, debuting in the Soyuz a new, much larger spacecraft which would participate in multiple rendezvous and docking manoeuvres, and possibly even crew transfers, with one or more other manned spacecraft.

Such a space feat has yet to occur, but the mysterious recent space missions of Cosmos-186 and 188 suggest that the Soviets have something of the sort in mind for the future, and are still quietly working to develop the techniques that they will need for lunar landing missions and/or a space station programme.

It Takes Two to Rendezvous

On 27 October, Cosmos-186 was launched into a low Earth orbit, with a perigee of 129 miles and an apogee of 146 miles and an orbital period of 88.7 minutes. Cosmos-187 was launched the following day, and there has been speculation that it was intended to be part of a rendezvous and docking demonstration with Cosmos-186 but was placed into an incorrect orbit. However, as is so often the case with Cosmos satellites, the Soviet authorities only described their missions as continuing studies of outer space and testing new systems, so the actual purpose of this mission remains a mystery.

A rare Soviet illustration of what is believed to be the Cosmos-186-188 docking

However, Cosmos-186 was joined by a companion on 30 October, when Cosmos-188 was placed into a very similar orbit with a separation of just 15 miles. This clearly demonstrates the precision with which the USSR can insert satellites into orbit. The two spacecraft then proceeded to perform the first fully automated space docking (unlike the manual dockings performed by Gemini missions from Gemini-8 onwards), just an hour after Cosmos-188 was launched. Soviet sources, and some electronic eavesdropping by the now-famous science class at Kettering Grammar School in England, using surprisingly unsophisticated equipment, indicate that Cosmos-186 was the ‘active’ partner in the docking. It used its onboard radar system to locate, approach and dock with the ‘passive’ Cosmos-188.

While the two spacecraft were mechanically docked, it seems that an electrical connection could not be made between them, and no other manoeuvres appear to have been carried out while Cosmos-186 and 188 were joined together. Perhaps there were technical issues surrounding the docking, but an onboard camera on Cosmos-186 did provide live (if rather low quality) television images of the rendezvous docking and separation, and some footage was publicly broadcast.

After three and a half hours docked together, the two satellites separated on command from the ground and continued to operate separately in orbit. Cosmos-186 made a soft-landing return to Earth on 31 October, lending credence to the speculations that it was testing out improvements to the Soyuz parachute system, while Cosmos-188 reportedly soft-landed on 2 November.

Speculating on Soviet Space Plans

Was Cosmos-186 a Soyuz-type vehicle, possibly testing out modifications made to prevent a recurrence of the re-entry parachute tangling that apparently led to the loss of Soyuz-1 and the death of Cosmonaut Komarov? Building on speculations from the time of the Soyuz-1 launch, there have even been suggestions that Cosmos-186, while unmanned, was a spacecraft large enough to hold a crew of five cosmonauts. There is also speculation that Cosmos-188 may have been the prototype of a new propulsion system for orbital operations. Does this mean, then, that the USSR is planning some kind of manned spaceflight feat in orbit to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Communist Revolution? Or that it will soon attempt a circumlunar flight, to reach the Moon ahead of the United States?

Whatever their future plans may be, the automated rendezvous and docking of two unmanned spacecraft in Earth orbit shows that the USSR’s space technology is still advancing rapidly. The joint Cosmos 186-188 mission proves that it is possible to launch small components and assemble them in space to make a larger structure, even without the assistance of astronauts. This means that massive rockets like the Saturn V might not be required to construct space stations in orbit, or even undertake lunar missions, if the project is designed around assembling the lunar spacecraft in Earth orbit. Has the Cosmos 186-188 mission therefore been a hint of what the USSR's Moon programme will look like, in contrast to Apollo? Only time will tell…

by Kaye Dee

Back in November last year, while writing about Gemini 12, I asked “where are the Russians?”, since there had not been a manned Soviet space mission since Voskhod 2, in March 1965. I didn't expect that when I finally came to write about the next Soviet space flight, it would be to report the first death to occur during a space mission: an incident as deeply shocking as the Apollo 1 fire just three months ago. Sadly, the return of Soviet manned spaceflight and the introduction of its new Soyuz spacecraft (the name means “Union” in Russian) has been mared by the death of its crew and the destruction of the spacecraft itself.

Re-entry Mishap

Early yesterday (25 April Australian time), after more than twelve hours of silence about the mission, the official Soviet newsagency TASS announced that Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov had been killed after the failure of the parachute on his Soyuz 1 spacecraft, following re-entry. As I write this, little is known about what actually happened, but it appears that the parachute lines became tangled in some way, preventing the chute from fully opening, so that the spacecraft smashed into the ground at high velocity. However, it is not clear whether Cosmonaut Komarov died before the spacecraft hit the ground, or whether he was killed on impact.

Newspaper article from the 25 April edition of The Canberra Times announcing the loss of Soyuz-1

New Spacecraft, Ambitious Mission

As is always the case with the USSR’s space programme, nothing was known about the Soviet Union’s latest space mission until it was safely in orbit. We now know that Soyuz 1 was the first flight of a new spacecraft, believed to be even bigger than the Voskhod, which, as we saw, could carry a crew of three. Moscow television has supposedly described the Soyuz as “huge”. Just as Mercury and Vostok, and Gemini and Voskhod, could be considered parallel programs, Soyuz is assumed to be the equivalent of Apollo, and part of the USSR’s Moon landing programme about which we know so little. Could the Soyuz be capable of carrying a crew of four, or even five cosmonauts?

Unconfirmed reports suggest that Soyuz 1 was intended to undertake a surprisingly ambitious mission for the shakedown flight of a new vehicle. The craft was apparently planned to rendezvous in orbit with at least one, and possibly two, other spacecraft, with between six and nine cosmonauts joining Komarov in space before the end of the mission. The low altitude of Komarov's orbits (the lowest to date in the Soviet manned programme), only 138 miles above the Earth, certainly hint that rendezvous and docking operations were included in the flight programme, as a low orbit conserves power resources. This would have been a significant spaceflight first indeed, especially if – as has also been rumoured – there were plans for a crew transfer between one of these other spacecraft and Soyuz 1.

Crew Transfers Planned?

The fact that Komarov was the only cosmonaut on board Soyuz 1 certainly gives the crew trasnfer rumour some credence, as cosmonauts from one or two other spacecraft could have transferred to Soyuz 1 to fill its empty crew couches. Of course, we have no idea whether this transfer would have taken place through a docking tunnel between two spacecraft, or via a spacewalk, since we know nothing about the Soyuz vehicle itself. However, unless the Soviet manned space programme has been conducting an equivalent to the Gemini programme in secret over the past two years, its cosmonauts have little rendezvous experience (apart from Vostok 3-4 and 5-6), no docking experience, and have conducted only one spacewalk, whereas NASA has firmly mastered these critical techniques needed for the Apollo Moon programme. Perhaps the USSR intended to start catching up by carrying out extensive practice of these techniques during this first Soyuz mission? Or perhaps they have largely ignored them because they are planning a completely different approach to their manned lunar programme?

The official photo of Cosmonaut Komarov, released when the Soyuz 1 mission was announced, shows him wearing a spacesuit similar to that worn by Cosmonaut Alexei Leonov when he made the world’s first spacewalk. This photo can be seen in the reproduction of the article from The Canberra Times, above. It offers an intriguing hint that Komarov himself was possibly intended to make a spacewalk, or swap into another spacecraft for his return to Earth. However, confusing the issue is the picture below, which shows Komarov walking to board Soyuz 1 wearing a flight suit (similar to the one he wore as commander of Voskhod 1) rather than a spacesuit.

Problems with the Soyuz Spacecraft?

So why didn’t this rumoured space feat take place? Soyuz 1 was launched on 23 April. No problems were publicly reported during the early orbits of the mission, and Cosmonaut Komarov sent greetings from space “to the hardworking Australian people”. In another message, he also slammed the Vietnam War, in which Australia is fighting alongside the United States and other allies, sending a propaganda broadcast from orbit: "My warm greetings to the courageous Vietnamese people, fighting with dedication against the bandit aggression of American imperialism for freedom and independence", he said.

So why didn’t this rumoured space feat take place? Soyuz 1 was launched on 23 April. No problems were publicly reported during the early orbits of the mission, and Cosmonaut Komarov sent greetings from space “to the hardworking Australian people”. In another message, he also slammed the Vietnam War, in which Australia is fighting alongside the United States and other allies, sending a propaganda broadcast from orbit: "My warm greetings to the courageous Vietnamese people, fighting with dedication against the bandit aggression of American imperialism for freedom and independence", he said.

Soyuz 1 returned from space on its 19th orbit, after just 27 hours in space. It seems unlikely that this was the intended mission duration if rendezvous/docking and spacewalks with multiple spacecraft were really planned. The shortness of the flight may therefore be an indication that there were problems with the spacecraft, which is not necessarily unexpected with the first flight of a new vehicle. No other spacecraft launched to rendezvous with Soyuz 1, so perhaps this aspect of the mission was abandoned when problems arose.

Reports from amateur space-trackers in Italy also claim that they picked up messages in which Komarov complained to the Soviet Mission Control that they were “guiding [him] wrongly” during re-entry. Whether problems with the Soyuz spacecraft in orbit were responsible for the parachute failure that caused Soyuz 1 to plummet to Earth is perhaps something that we may not know for decades, if ever, given the habitual secrecy of the Soviet space programme.

One of the few photos available showing what remained of Soyuz-1 after its imapct with the ground

Lost Cosmonaut

As commander of the earlier Voskhod 1 mission, Colonel Vladimir Komarov was one of the handful of Soviet cosmonauts already known to us in the West. At 40, he was the second oldest of the cosmonauts (after Voskhod 2 mission commander Pavel Belyayev) and the first cosmonaut to make two spaceflights. Said to be highly respected by his cosmonaut colleagues, Komarov overcame a heart murmur, similar to that which grounded Astronaut Donald K. "Deke" Slayton durng the Mercury programmme, and other medical issues to retain his place in the Soviet comsonaut team. He was

married with a 15-year old son and 9-year old daughter. Komarov's 38-year old wife wife, Valentina, has been quoted as saying that she did not even know her husband had been assigned to the Soyuz 1 flight until it was publicly announced after launch. The identity of the cosmonauts slated to fly the other other spacecraft due to be launched as part of Soyuz-1's mission is completeley unknown at this point.

Cosmoanut Komarov with his wife Valentina and daughter Irina

Accident or Incompetence?

Was the loss of Soyuz 1 and Cosmonaut Komarov’s death just a tragic accident? There are persistent rumours that the spacecraft was not actually ready to be flight tested, and that political pressure was brought to bear on the space programme to produce another significant achievement in advance of a major conference marking 50 years since the October Revolution. Another question that arises is whether or not the unexpected death in January 1966 of Chief Designer Sergei Korolev (whose identity was only revealed after he passed away), could have had any impact on the development of the Soyuz and its subsequent fatal first flight?

Was the loss of Soyuz 1 and Cosmonaut Komarov’s death just a tragic accident? There are persistent rumours that the spacecraft was not actually ready to be flight tested, and that political pressure was brought to bear on the space programme to produce another significant achievement in advance of a major conference marking 50 years since the October Revolution. Another question that arises is whether or not the unexpected death in January 1966 of Chief Designer Sergei Korolev (whose identity was only revealed after he passed away), could have had any impact on the development of the Soyuz and its subsequent fatal first flight?

Professor Sergei Korolev, the formerly anonymous Chief Designer of the Soviet space programme

An Honoured Hero

Like the lost crew of Apollo 1, Col. Komarov is a hero of the quest to explore space and has been posthumously awarded his second Hero of the Soviet Union medal and Order of Lenin. A Kremlin statement expressed the "profound grief" of the Soviet leadership at Komarov's death, and was signed by the Communist Party Central Committee, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet and the

Council of Ministers. A ten-minute public announcement of Komarov's loss on Moscow television showed the Soviet space monument and a black-bordered version of the official photo of Komarov wearing his spacesuit, while Moscow radio is said to have played sombre music. Komarov’s funeral will be held today, after which his ashes will be interred in the Kremlin Wall. The United States requested permission from the Soviet authorities for two astronauts to attend the funeral as a mark of respect, but disappointingly this was turned down.

Presumably the USSR will now launch an accident investigation similar to that being conducted by NASA to find the causes of the Apollo 1 fire, and will place the Soyuz programme into a hiatus until the invetsigation is complete. With both participants in the Moon race now investigating tragic accidents that have led to the loss of astronaut and cosmonaut lives, will the Moon race ever resume? Or will both programmes instead return to spaceflight with different goals? Only time will tell….