by David Levinson

Dodging the issue

Conscription has been part of American military planning for a little over a century, and it’s never been popular. From the draft riots of the Civil War to young men burning their draft cards today, there has always been resistance. During the Civil War, wealthy men could hire substitutes to go in their stead, and during the First World War, selection was done by local draft boards, which were subject to local pressure and tended to draft the poor. The interwar period saw the introduction of the lottery system in an effort to overcome the inequities of the past, and, with a brief return to local draft boards during World War Two, it has persisted to today.

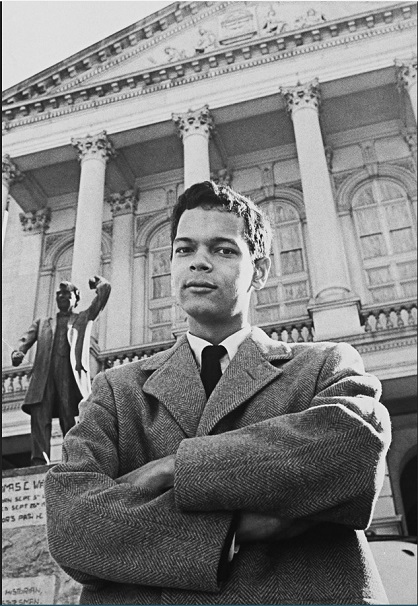

On January 6th, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee became the first Black civil rights organization to come out against the draft, citing the lack of freedom at home for so many and the fact that Blacks are over-represented. This statement gave the Georgia House of Representatives an excuse to refuse seating the newly elected Julian Bond. Mr. Bond is one of the founders of the SNCC and endorsed the statement issued by the group. He is probably also the most visible of the eleven Black men recently elected to the Georgia House. The claim was that by endorsing the opposition to the war and the draft, he could not swear to uphold the constitution of the United States.

Julian Bond outside the Georgia House. What possible objection could they have to him?

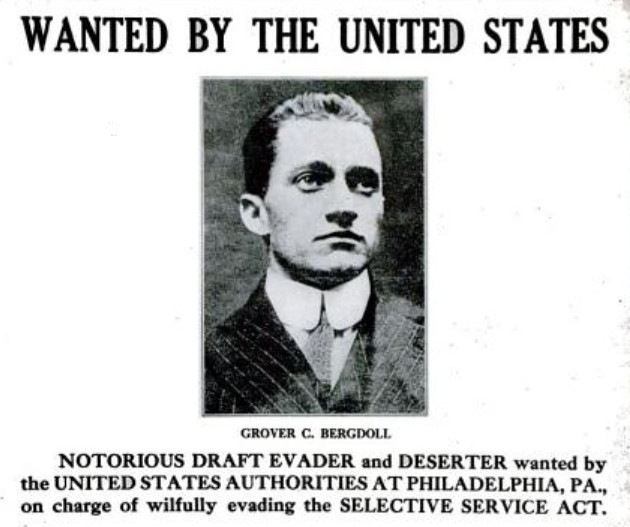

A long tradition

It is timely that, amid the draft protest furor, January 27th saw the death of Grover Cleveland Bergdoll, once known as America’s most notorious draft dodger (or 'slacker' as they were called during and after WWI). The scion of a wealthy Philadelphia brewing family, he enjoyed a playboy lifestyle before the war. He drove race cars and was one of the first people to learn to fly, even owning a Wright Model B. He registered for the draft, but failed to appear for a physical and was declared a deserter. He managed to stay on the run for two years, but was finally arrested in 1920 in his family home, with his mother waving a gun and threatening the authorities. Sentenced to five years, Bergdoll was released under guard to recover an alleged cache of gold, but he escaped and eventually made his way to Germany. There were two attempts to kidnap him, both ending disastrously for the would-be kidnappers. He married a German woman and settled down, though he made two extended trips back to America. He returned to the States for good with his family in 1939. Sentenced to serve the rest of his original term and an additional three years, he left prison in 1944 and moved to Virginia. He died of pneumonia, aged 72. He is survived by his ex-wife and eight children.

Bergdoll’s original wanted poster.

The issue at hand

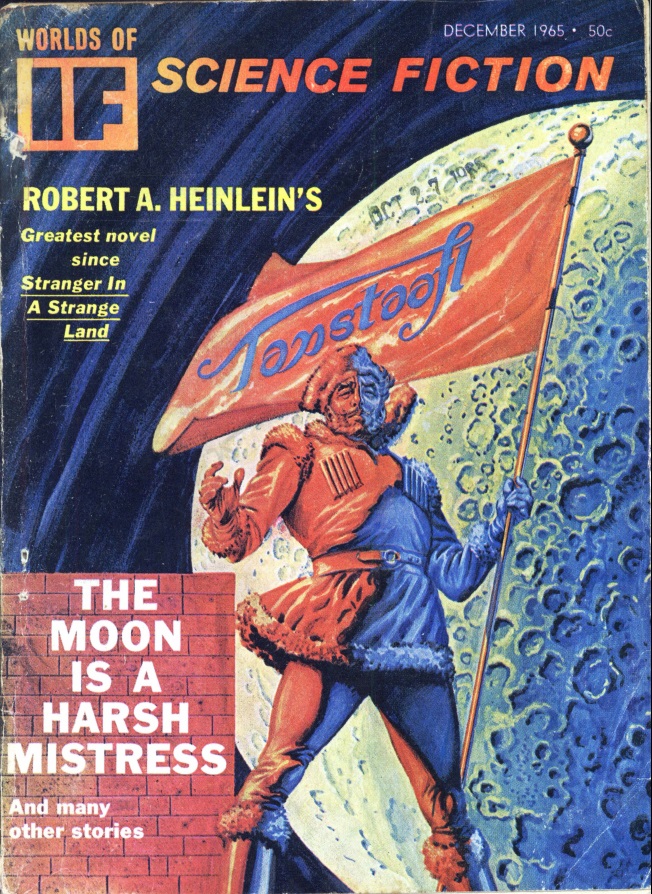

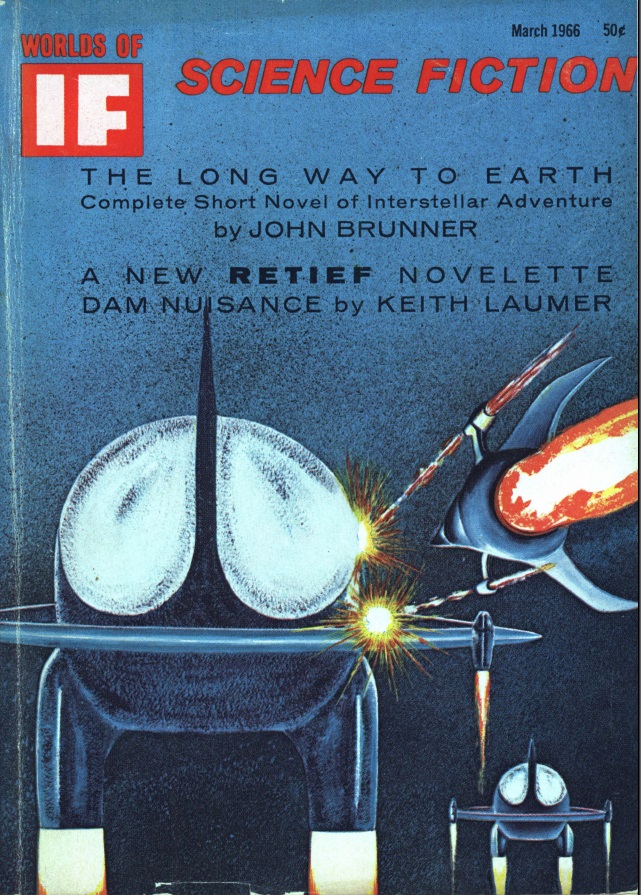

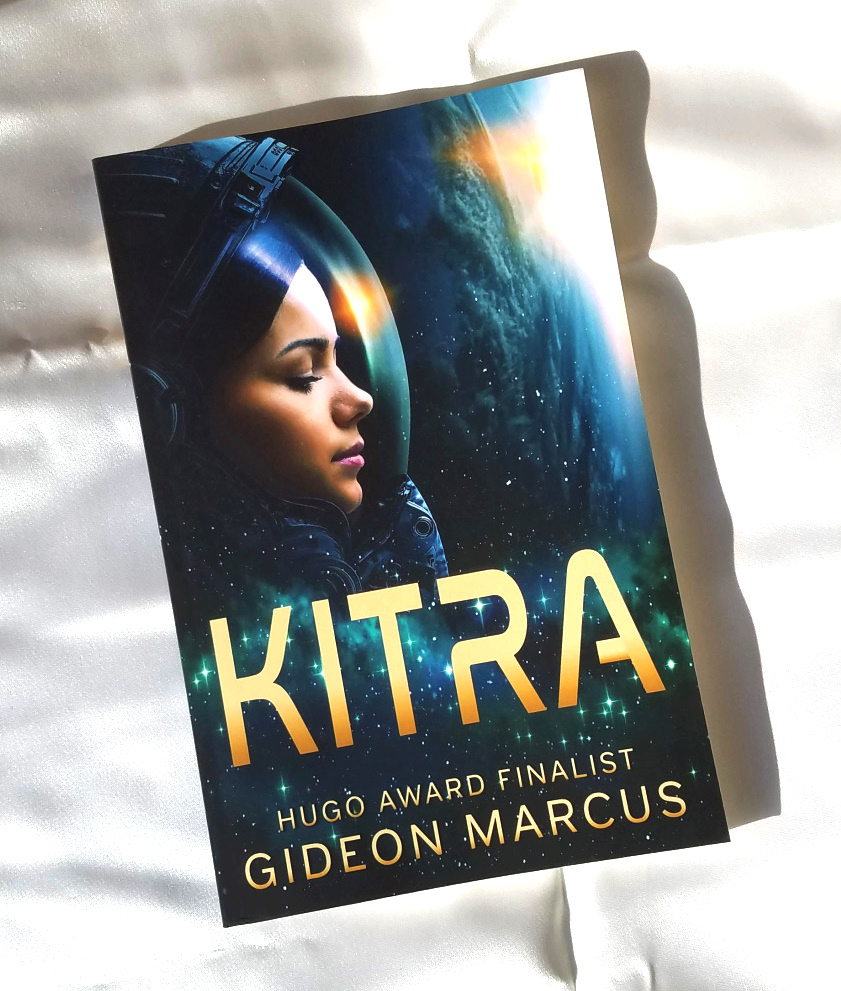

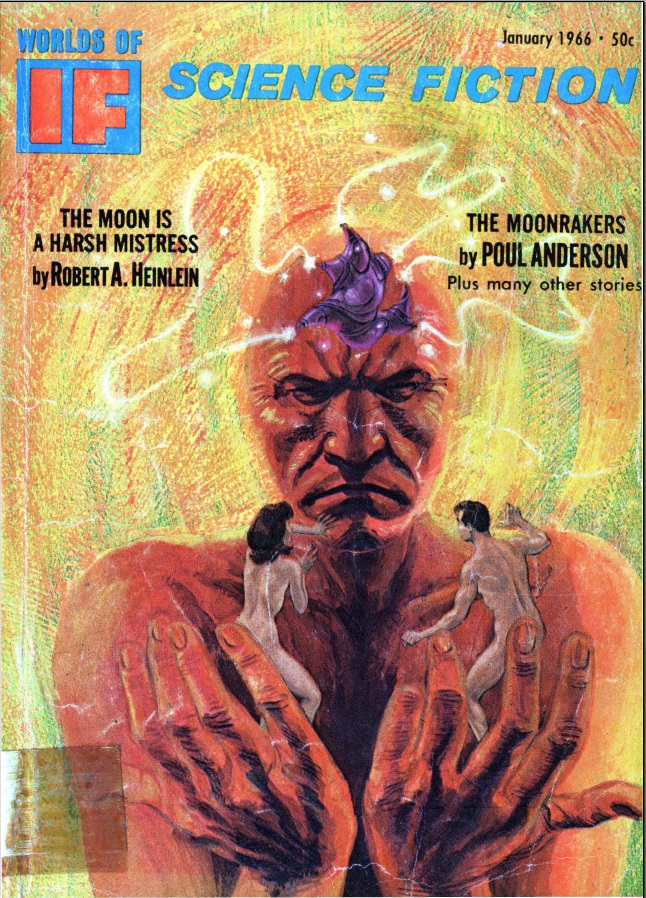

In the theme of this heightened era of military involvement (and lack thereof) this month’s IF plays host to several seasoned veterans, as well as the monthly new recruit. The stories range in quality from 1-A to not quite 4-F. The cover is even given to a story about a draft dodger, though one not one tenth as interesting as Grover Bergdoll.

A drab cover for a drab story. Art by Hector Castellon

The Long Way to Earth, by John Brunner

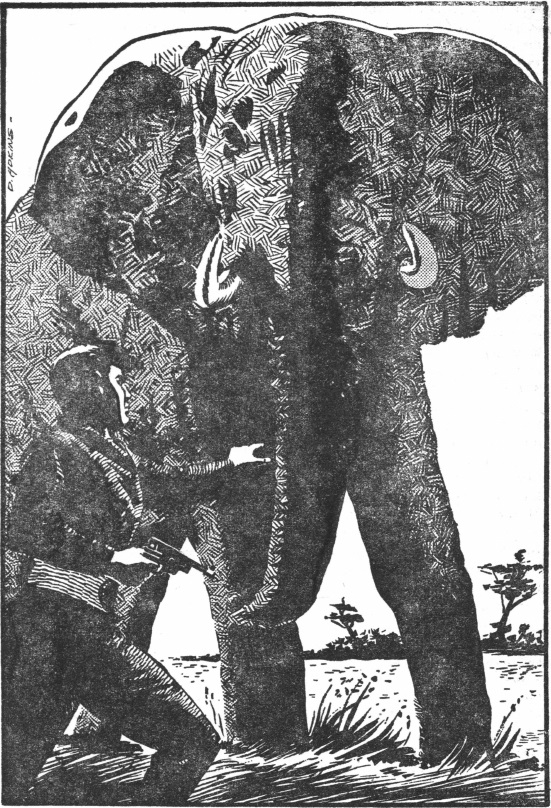

Kynance Foy has a problem. Armed with a degree in qua-space physics and an encyclopedic knowledge of interstellar commerce and law, she left Earth for the outer worlds to make her fortune. But the farther out she has gone, the harder it is for a Terran to find employment, and now she can’t even scrape up the price of a ticket home. Which is why the prospect of a job that pays nearly five times the going annual wage and offers repatriation at the end of the contract it too good to pass up. The catch is that she has to spend a year as the only person on a remote planet.

The man in charge of the project is only too happy to give her the job after she rebuffs his crude advances. It’s only on arrival that she discovers just how easy it is to breach her contract and be denied so much as passage off the planet, as has happened to every other person to hold the job. When a handful of her predecessors turn up, she knows that so much as acknowledging their existence will terminate her contract, but Kynance has a plan.

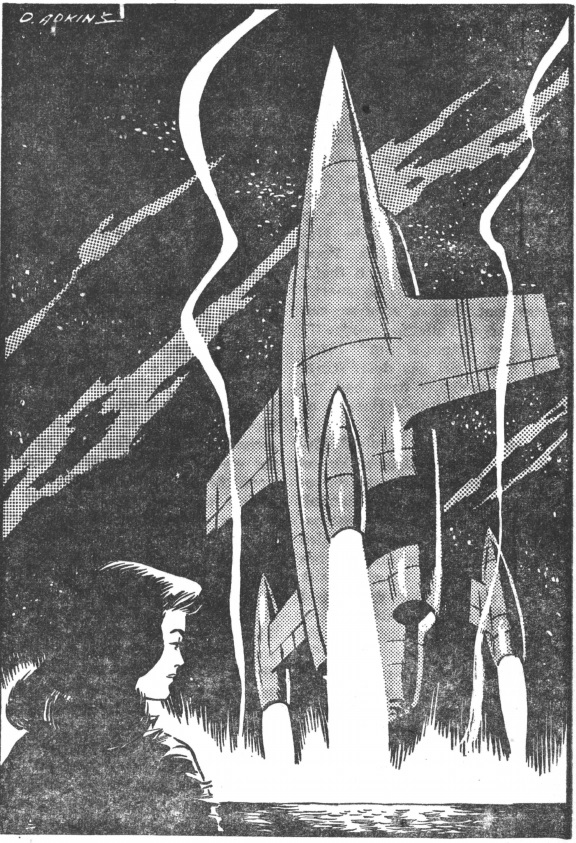

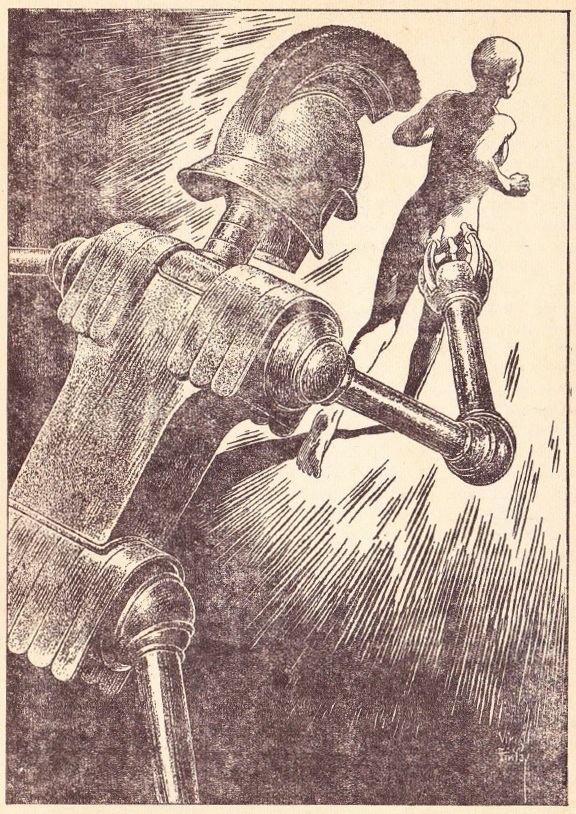

Executive Shuster is about to get the surprise of his life. Art by Adkins

This is a solid story: Brunner at his best writing a more traditional tale. Which is not quite as good as Brunner at his best when writing a more modern tale, but still good. Kudos for a woman protagonist who, while beautiful, gets by on her brains and is an active, driving force of the narrative. Three stars.

Ouled Nail, by H. H. Hollis

Our unnamed narrator runs into rocket jockey Gallegher in a New York bar. Galllegher works the Earth-Mars run, where a man spends months alone between planets and can go more than a little stir-crazy. He launches into a long tale of his friend Pick Pratt, who seems to have come up with a way to help spacers get over their stress.

Hollis is this month’s first time writer. This is something of a stereotypical science fiction bar tale, but I can’t say I enjoyed it much. Gallegher is an obnoxious narrator and the conclusion has holes you could fly a fleet of spaceships through. The Ouled Nail of the title are an Algerian tribe known for sending out their women to work as dancers and courtesans in the oases and towns near where they live. I had not heard of them before, so the best thing I can say for this story is that it sent me to the library to learn something. Two stars.

Dam Nuisance, by Keith Laumer

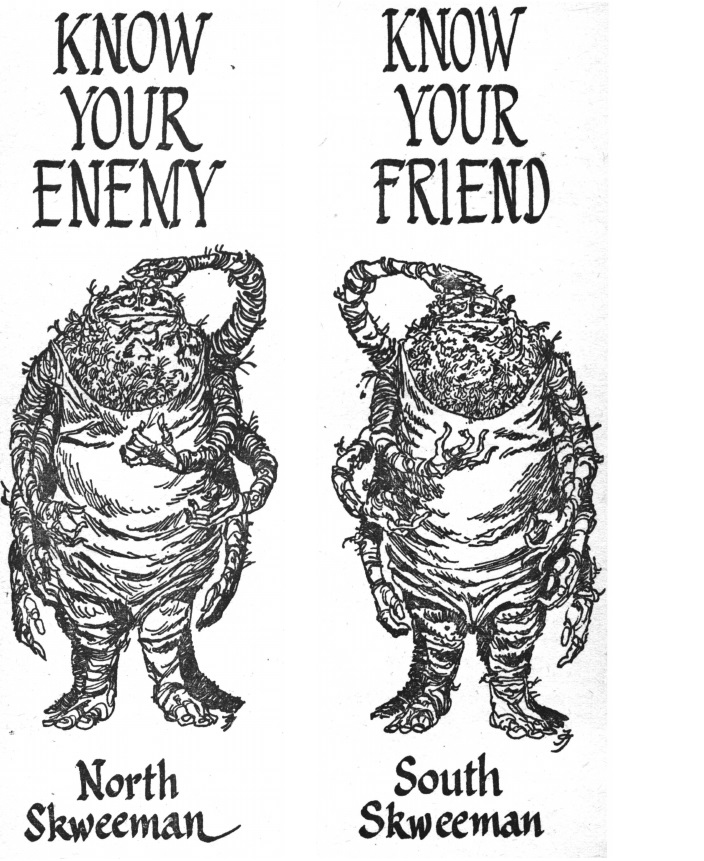

Retief is back. This time out, the CDT is supporting South Skweem, while the Groaci are backing North Skweem. Ambassador Treadwater is trying to come up with a grand public works project, but policy says it can’t be useful. Meanwhile, the Groaci are building a dam for North Skweem, one which is causing a drought in half of South Skweem and flooding the other half. To top things off Ben Magnan has disappeared while paying a courtesy call to the Groaci mission. As usual, it’s up to Retief to put everything to rights.

The differences are apparent to any right-thinking diplomat. Art by Gaughan

Even I am beginning to grow weary of Retief. Like a song that plays every single time you turn on the radio, it doesn’t matter how good it might be, it’s getting old. The worst part is the wasted opportunity. Laumer is clearly drawing on the situation in South-east Asia, with a bit of the Aswan Dam thrown in. That’s a set-up for biting satire – which we know he’s capable of writing – but instead we get a retread. Someone who’s never read a Retief story might enjoy this, but regular readers can only sigh over what might have been. A very low three stars.

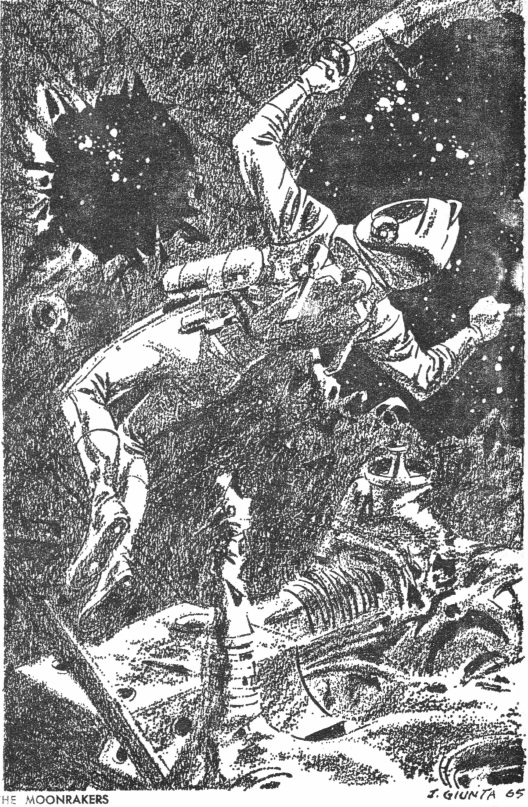

Draft Dodger, by Kenneth Bulmer

Hugo Lack has received his call-up notice to the Terran Space Navy. Desperate to avoid serving, he visits draft-dodging facilitator Jerky Jones, but about the only thing he can afford is an irreversible lobotomy. Lack is soon scooped up by the Navy and enters a dream-like, almost fugue state that sees him through boot camp and deployment. He winds up in the quartermaster corps in an out-of-the-way base, but one day the war comes to him.

What a dull, dull story. It’s not terribly engaging to begin with, but when Hugo enters his sleepwalking state, the narrative voice follows him. Bulmer is trying to say something about the way the military creates heroes and the ungrateful people back home, but mostly he perpetuates the idea that the only reason someone might not want to “do his duty” is cowardice. Two stars.

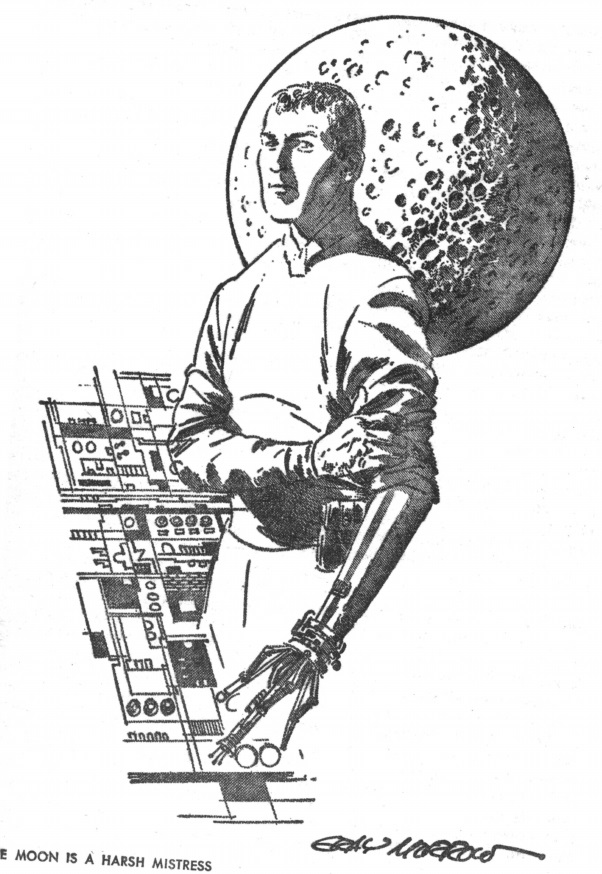

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (Part 4 of 5), by Robert A. Heinlein

Revolution has come to the Moon, and now it’s time for someone to travel to Earth and make the case for independence. After a harrowing journey in a cargo pod, Mannie and Prof arrive in India. They spend some time appearing before a supposedly new UN committee, but which is actually the committee overseeing the Lunar Authority. During an extended break, they go on a whirlwind tour of the Earth, with Mannie using ploys developed by Mike and Prof to drive wedges between various factions. Returning to India, they are presented a plan from the committee to turn all free Loonies (some 90% of the population) into client-employees. If they don’t like it, they can be repatriated to Earth, where most of them have never been and none can live comfortably.

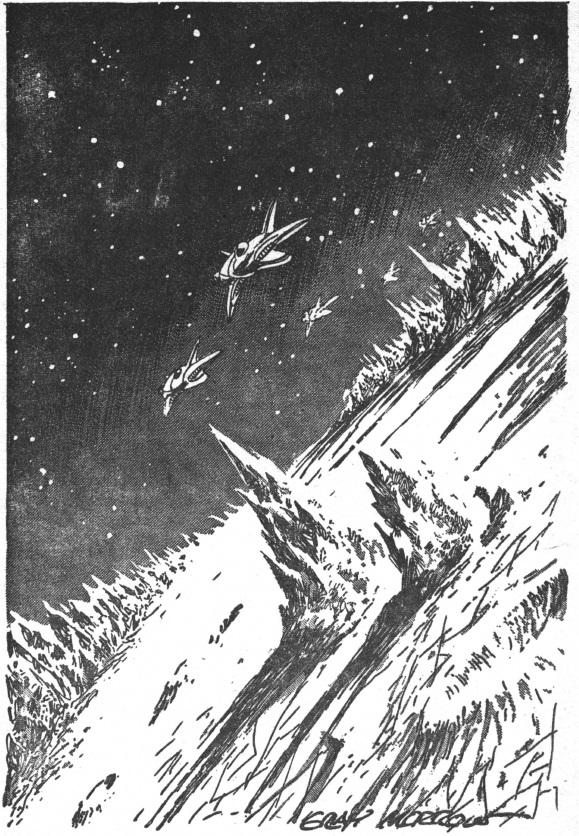

As the situation turns bad, Mannie and Prof make their escape, assisted by Stu and return to the Moon. The events of the trip make excellent propaganda to fire up the people, and there is now a duly elected government in place. With a bit of manipulation, Prof winds up as Prime Minister and Secretary of State, Wyoh is Speaker pro tem and Mannie is Minister of Defense. An embargo is imposed on the shipment of grain Earthside and a grain pod is fired at an unpopulated part of the Sahara to show that the Moon can defend itself. And then Earth invades. Troop ships sent on long orbits come in from the back of the Moon where Mike can’t see them. War has come to the Moon. To be concluded.

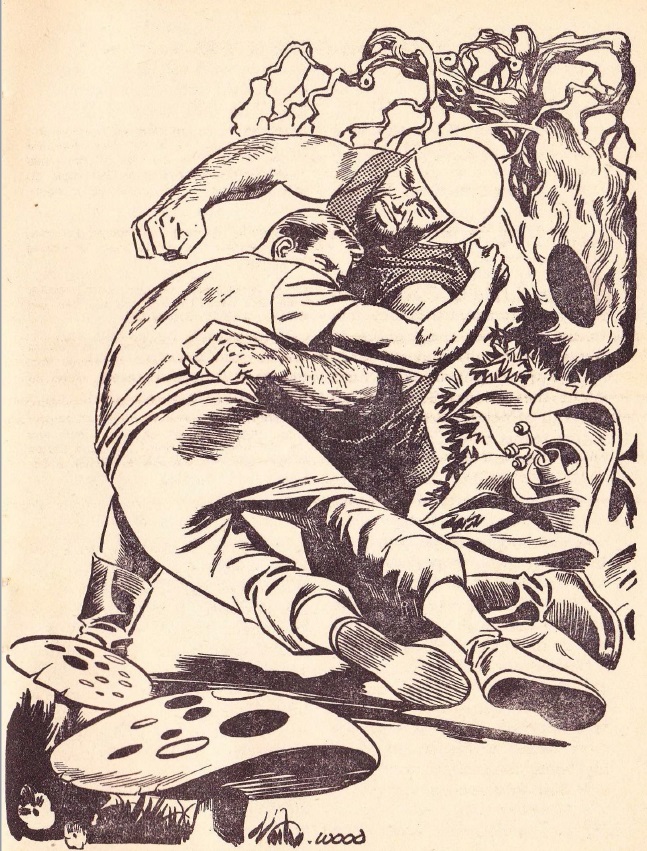

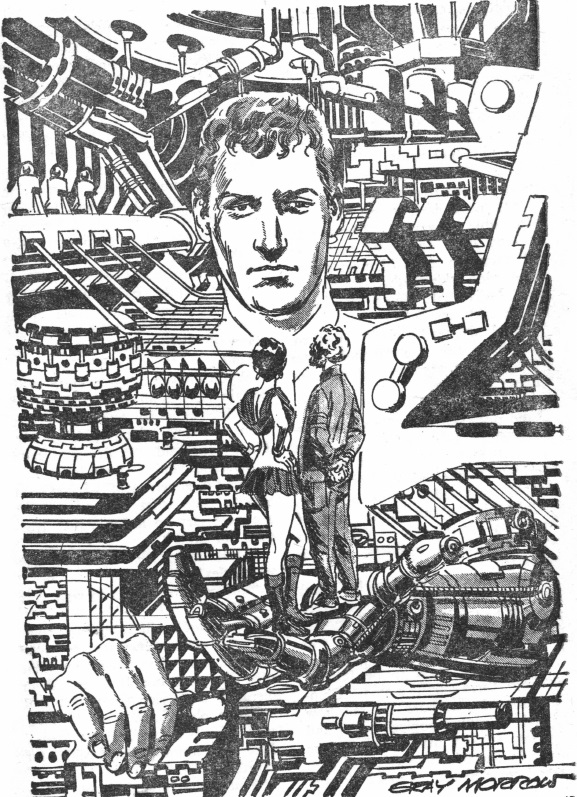

The Earth strikes back! Art by Morrow

Heinlein continues to excel. We get what is probably the most action we’ve seen, with the promise of more next time, but most of the story is committee meetings, back-room deals and political wrangling. And it’s still compelling! We do get one bit of pure Heinleinian didacticism when Prof trots out a parable of a man whose job is polishing the brass cannon on the courthouse lawn and one day quits his job, sells everything he has and buys his own cannon to go into business for himself. I understand Heinlein wanted to call this book The Brass Cannon. Fortunately, he was talked out of it. Anyway, four stars and I eagerly await the conclusion.

Summing Up

Once again, Heinlein shines out brightly. A couple of Journey writers have noted that there are two John Brunners: the exciting New Wave writer and the conventional writer for the American market. He’s managed to bridge the gap slightly this time, though he's still much closer to the second Brunner than the first. After that, it’s Laumer going through the motions and some sub-par filler. I have to say, that doesn’t fill me with a lot of confidence about what happens once the current serial ends.

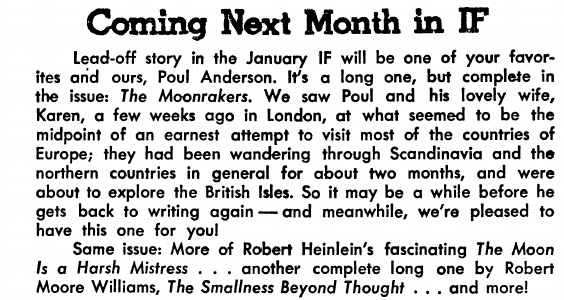

This seems like an unusual pairing, but it’s nice to see the return of Rosel Brown.

![[February 8, 1966] Feeling A Draft (March 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-641x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1966] Getting There Is Half The Fun (March 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n06_1966-03_Anon.Malefactor_0000-3.jpg)

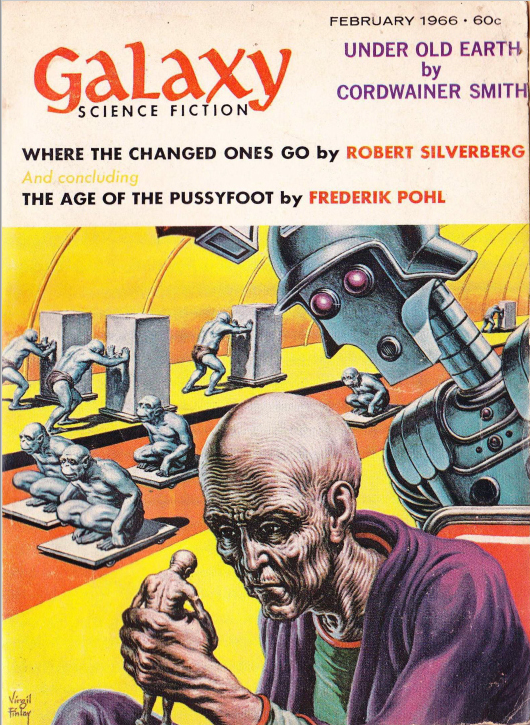

![[January 8, 1966] Seems like old times (February 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/660108cover-530x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

![[December 18, 1965] Bulges and Depressions (January 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651216cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 2, 1965] Superiority Complex (January 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IF-1966-01-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[November 16, 1965] Crime and Punishment (January 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n05_1966-01_dtsg0318.Anon_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1965] Doldrumming (December 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/amz-1265-cover-481x372.png)

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 2, 1965] Revolution! (December 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IF-1965-12-Cover-652x372.jpg)