by John Boston

Hope Springs Eternal

. . . but, as Groucho Marx might put it, hope springs can get rusty, too.

The June Amazing on its face presents bad news and good news. In the first category is the beginning of a new two-part serial by Murray Leinster, generically titled Stopover in Space. One can only hope (that word again!) that there is more to it than the empty blather of Killer Ship from last year.

by James B. Settles

All the shorter stories are reprints. But two of them are by very reputable authors, Arthur C. Clarke and Henry Kuttner, taken from the magazine’s ambitious false spring of 1953-54 (the Renascence), and two others are from the immediately post-Ray Palmer times (the Liminal Period), by writers who later made pretty good names for themselves, Walter M. Miller, Jr., and Kris Neville. The fifth is the last published story by G. Peyton Wertenbaker, who commendably learned to write after the fiascoes of The Man from the Atom and its sequel.

Of course the Clarke and Kuttner stories are not exactly rediscoveries. Clarke’s Encounter in the Dawn, retitled Expedition to Earth, was the title story of the first collection of his stories, published by Ballantine in 1953 and pretty widely known. Kuttner’s Or Else was the lead story in his collection Ahead of Time, also from Ballantine in 1953. It was anthologized in the UK in Edmund Crispin’s first Best SF volume, and reprinted again in last year’s The Best of Kuttner from the UK’s Mayflower Books. These stories will probably be familiar to those well read in SF.

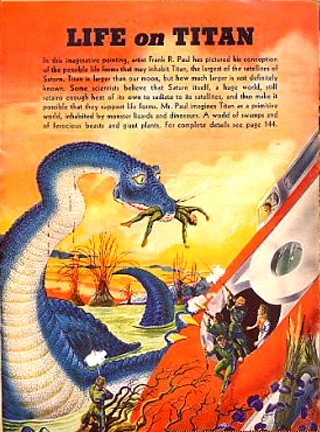

The rest of the package is as usual: another inanely self-serving editorial by editor Ross and a few letters mostly praising the reprint policy, though one of the correspondents also says don’t overdo it with the reprints, it’s time for more Robert F. Young and Ensign De Ruyter. He appears to be serious. The cover, simultaneously dull and busy, is reprinted from the back cover of the July 1942 Amazing. It’s called Satellite Space Ship Station, and artist James B. Settles provides a rather pedestrian view of space travel.

Stopover in Space (Part 1 of 2), by Murray Leinster

by Gray Morrow

As is my habit, I will hold off reading or commenting on the serial until I have both installments. I am struggling to reserve judgment, but can’t fail to notice that the same egregious padding that so distinguished, or extinguished, last year’s Killer Ship shows up in the first paragraph here: “Scott ran into the situation on a supposedly almost-routine tour of duty on Checkpoint Lambda. It was to be his first actual independent command as a Space Patrol commissioned officer. Otherwise the affairs of the galaxy seemed to be proceeding in a completely ordinary fashion. On a large scale, suns burned in emptiness, novas flamed, and comets went bumbling around their highly elliptical orbits just as usual.”

If This Be Utopia, by Kris Neville

First after the serial is Kris Neville’s If This Be Utopia, from the May 1950 issue, a slightly heavy-handed satire about a regimented future in which everyone is assigned to a job and pressured mercilessly to perform, and those who don’t measure up—or are made examples of by their superiors—get demoted to worse fates. Our hero is a middle manager who is cracking under the stress and taking it out on his underlings until his superiors take it out on him. It’s a bit too obvious, but still decently done. Three stars.

Encounter in the Dawn, by Arthur C. Clarke

Encounter in the Dawn, from the June-July 1953 issue, is fairly typical for Clarke, a sort of lecture-demonstration of the stuff of SF and his understanding of the cosmos, without too much in the way of plot. But that’s OK. Clarke’s writing skill and his restrained sentimentality about the vastness of the universe and the depths of time carry the reader along. He’s the antithesis of Ray Palmer’s policy of “Gimme bang-bang.”

This one begins: “It was in the last days of the Empire,” which is threatened by an unspecified “shadow that lay across civilization.” Three regular guys of the Galactic Survey, continuing their quest for knowledge despite the doom overhanging their homes, arrive at a new solar system and land on what is obviously Earth. They take a look around and befriend Yaan, a primitive human or proto-human, with gifts of game killed by their robot. They get the call to come home for the Empire’s last stand, leave Yaan a few high-tech gifts like a flashlight, and take off. Tragedy looms over them, but life and intelligence will go on. Three stars.

Or Else, by Henry Kuttner

Kuttner’s Or Else (August-September 1953 issue) is well done also, as one would expect, but there’s not much to it. A couple of Mexican subsistence farmers are shooting at each other, contesting the ownership of the only source of water in their valley. An alien drops in by flying saucer, demonstrates various superpowers, says his race has appointed themselves peacekeepers of the solar system, and Miguel and Fernandez have to stop trying to kill each other because violence is wrong. They agree and shake hands, the alien buzzes off, and they start shooting again because there’s still only one water hole in the valley.

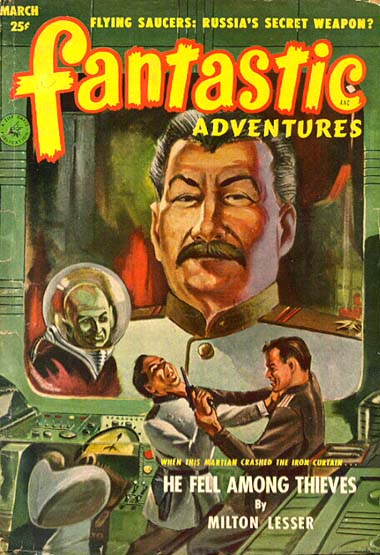

by Dick Francis

Profound, huh? While SF may occasionally contribute to the global dialogue on war and peace, this one is best described as chewing less than it purports to bite off. It also relies on cartoony ethnic stereotyping—but then everything in the story is pretty cartoony, and Kuttner at least lends the viewpoint character, Miguel, some shrewdness. Thinking the alien is really a norteamericano, he says, “First you will bring peace, and then you will take our oil and precious minerals.” Two stars for execution, not much for substance.

Secret of the Death Dome, by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s first published SF story, Secret of the Death Dome (January 1951 issue), is another kettle of sweat altogether, the kind of thing you’d expect to find in a magazine whose cover depicts a hairy-chested guy wrestling with a crocodile.

The Martians have landed, and how: they have plunked down a large and impervious dome in the desert (actually, a couple of feet above it), where they engage in cryptic communication, and snatch anyone who comes too near and vivisect them. One guy came back without his legs. The newly wed Barney came back without his genitals, falling off his horse and dying on arrival. (The Martians are surveilled by the military on horseback.)

by B. Edmund Swiatek

This makes Jerry mad. Barney was his best friend and Barney’s new wife was Jerry’s old flame. So Jerry, who can’t sleep, saddles up and heads out, to do . . . what? He has no idea. The Martians scare his horse away, and he hears from base that when it came back riderless, Betty—the widowed Mrs. Barney—took it and is on her way. So he heads toward the dome and crawls under it looking for a way in.

You can guess the rest. He’s captured, gets control of the situation through brains and guts, rescues the by then-captured Betty, sowing death and destruction among the Martians all the way, learns why they are here (the secret of the title, including what the Martians wanted with Barney's genitalia), and drives them away forever. Whew! The details don’t matter. At the end, the just-bereaved Betty tells Jerry not to contact her—“. . . for a couple of months, anyway,” the back of her neck flushing as she turns away.

The style is consistent with the content, cynical tough-guy-isms all the way down. For example, when the colonel gets the call that Barney has returned, he sends Jerry to check things out. “Jerry was just a sergeant, but there wasn’t any need for brass. Death is for privates.” And so on. Two stars for this testosterone-soaked epic.

Elaine’s Tomb, by G. Peyton Wertenbaker

G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s Elaine’s Tomb, from the Winter 1931 Amazing Stories Quarterly, is, in its quaint way, the best of this issue’s short fiction, and a vast improvement over his earlier work. Alan, the narrator, teaches at a small college and falls in love with Elaine, one of his students. Of course he doesn’t do anything about it, and hares off to Egypt with his colleague Weber who has a line on some ancient temples hardly anybody else knows about. He confesses his romantic situation to Weber en route. In a temple, there’s a preserved ancient Egyptian king, and a carved curse against anybody who molests him. Alan touches the recumbent body, and shortly comes down with a fever that shows no sign of abating. But Weber has found the secret of suspended animation, and promises to put Alan under at the moment of death, and revive him when he finds the secret of life, which must be around the temple somewhere, and unite him with Elaine.

by Leo Morey

Alan awakens, and it’s the far future, Wellsian variant, populated by people who have forgotten most of the know-how of civilization; the machines take care of them, and when one breaks down, they just put another one in its place. They live pleasant lives and some of them even write books. In one of these, Alan learns of Elaine’s Tomb, up north near what used to be called Chicago, in the frozen barbarian-populated wastes. Turns out Weber couldn’t revive him, but he could suspend Elaine to wait for him. Further adventures and reunion (or union, in this case) follow.

The story is archaic in attitude but modern in its plain style, well imagined and visualized without wasted verbiage, with enough plot to sustain its 40-page length, and altogether a pleasure to read. Am I really going to give this antique four stars, as I did with another of Wertenbaker’s late stories, The Chamber of Life? Guess so.

Summing Up

So, hope fulfilled—admittedly, to expectations lowered by experience. That's because editor Ross this time selected modern stories, plus an older one that is written in a modern style and not centered around the cranky crotchets of bygone decades, unlike some earlier selections I would prefer not to name. The result is mostly pretty readable, with a couple of stories better than that, and nothing bloody awful. But the specter of the Leinster serial still looms over the next issue. We shall proceed with trepidation.

If you want to hear some great modern tunes, then tune in to KGJ, our radio station! Nothing but the newest hits!

![[May 8, 1966] A Respite (June 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510amz-0666-cover-575x372.png)

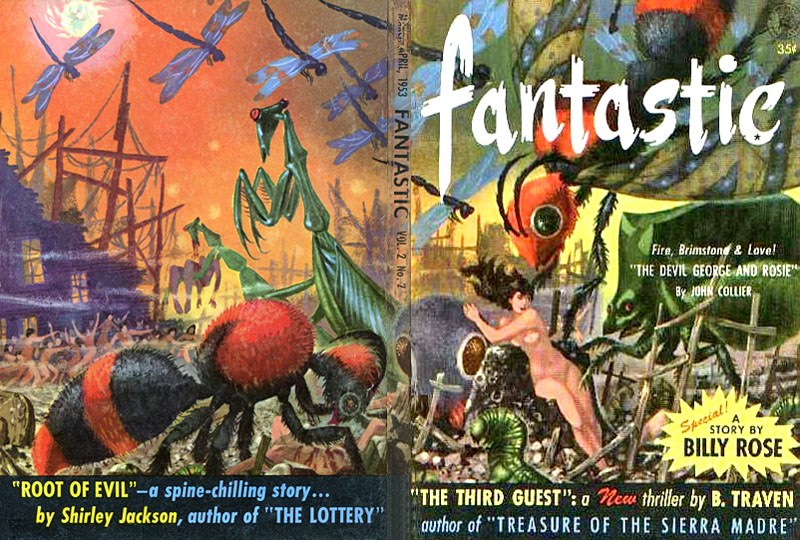

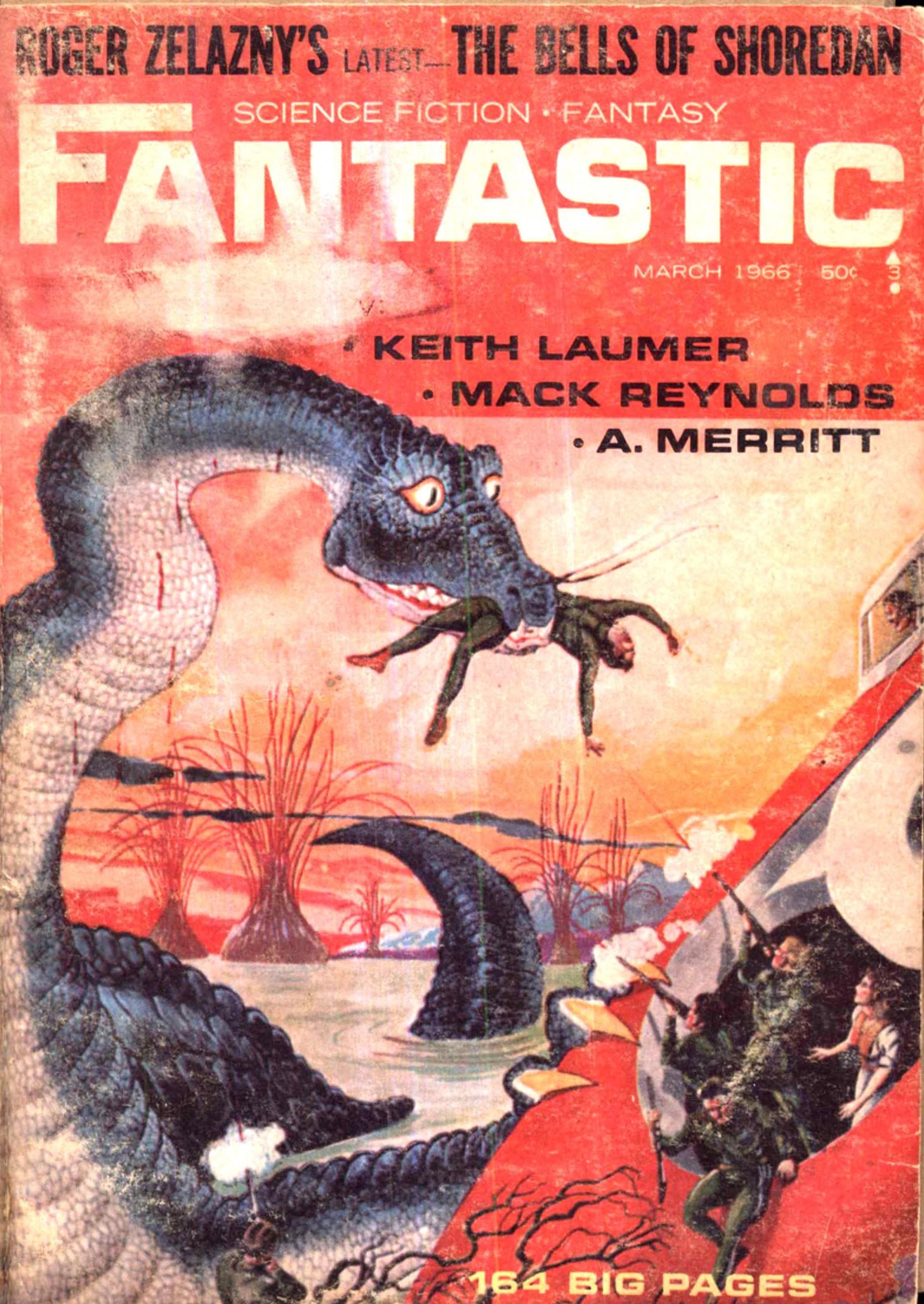

![[April 8, 1966] Search Parties (May 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Fantastic_v15n05_1966-05_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

![[March 14, 1966] Random Numbers (May 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n07_1966-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

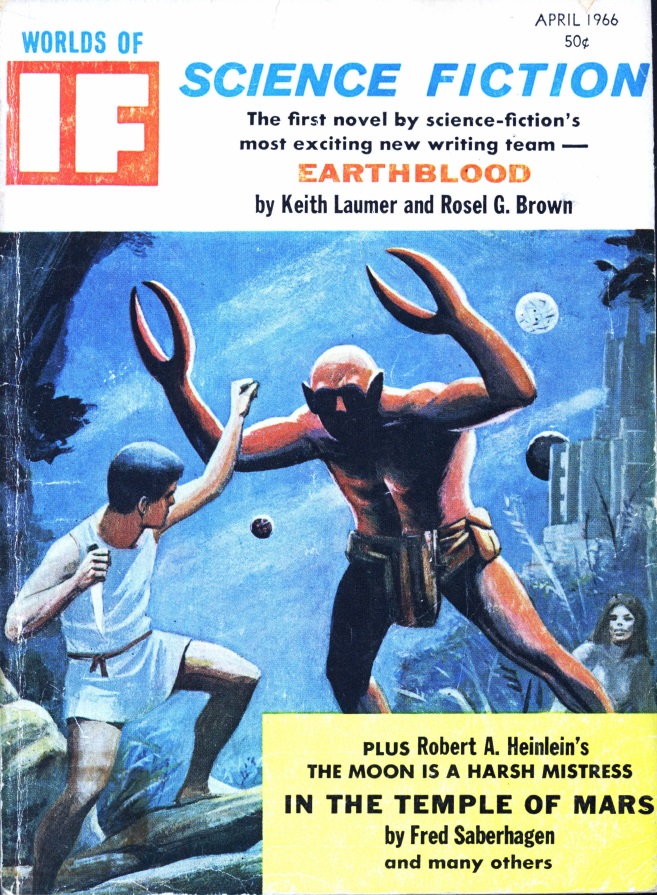

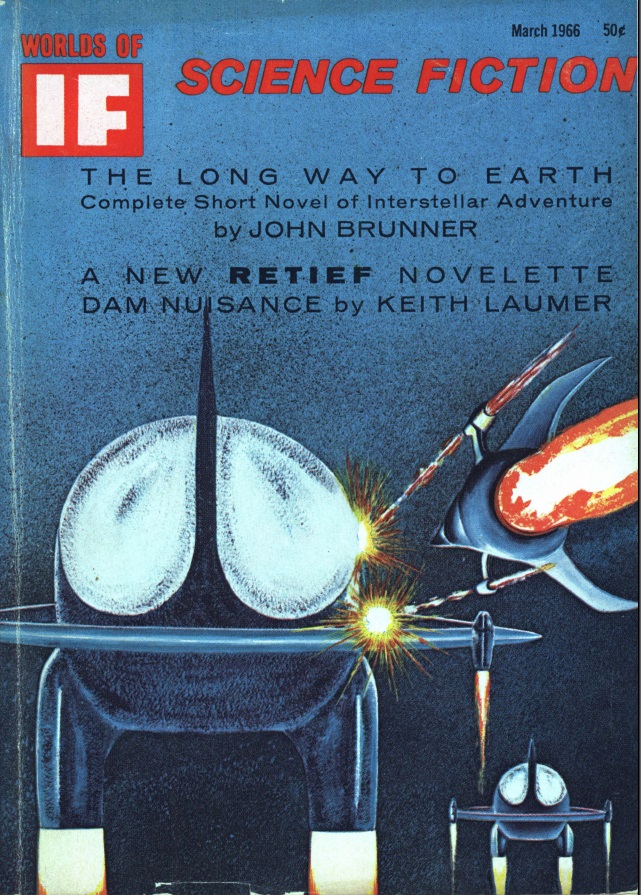

![[March 2, 1966] Words and Pictures (April 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-1-657x372.jpg)

![[February 18, 1966] Fixing up the old place (March 1966 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/660218cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1966] Past? Imperfect. Future? Tense. (March 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fantastic_v15n04_1966-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1966] Feeling A Draft (March 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-641x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1966] Getting There Is Half The Fun (March 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n06_1966-03_Anon.Malefactor_0000-3.jpg)

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

![[December 14, 1965] Expect the Unexpected (January 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fantastic_v15n03_1966-01_0000-3-672x372.jpg)