by Victoria Silverwolf

Peace on Earth? No. Peace Above Earth? Maybe.

With the conflict in Vietnam growing ever more bloody, and tensions building between the Soviet Union and China, it seems that war is here to stay on this sad little planet. Dare we look to the skies for a way to escape this endless chaos?

Although humanity is just starting to take its first baby steps into the cosmos, some folks are trying to make sure that it will be filled with plowshares instead of swords. Late last month, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union signed the so-called Outer Space Treaty.

President Lyndon Baines Johnson shakes hands with Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin at the signing ceremony. Barely visible between them are British ambassador Sir Patrick Dean and American ambassador Arthur J. Goldberg. I think that's American Secretary of State Dean Rusk at the podium. Don't ask me who the other folks are.

The agreement is formally known as The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. That's quite a mouthful, but what does it mean?

In brief, it bans nuclear weapons in space; limits use of the Moon and other extraterrestrial bodies to peaceful purposes; and prevents any nation from claiming sovereignty over any region of space or any celestial body. Of course, only three countries have signed it so far, and any treaty is only a piece of paper, so we'll have to wait to see what really happens outside the atmosphere. Hope for the best.

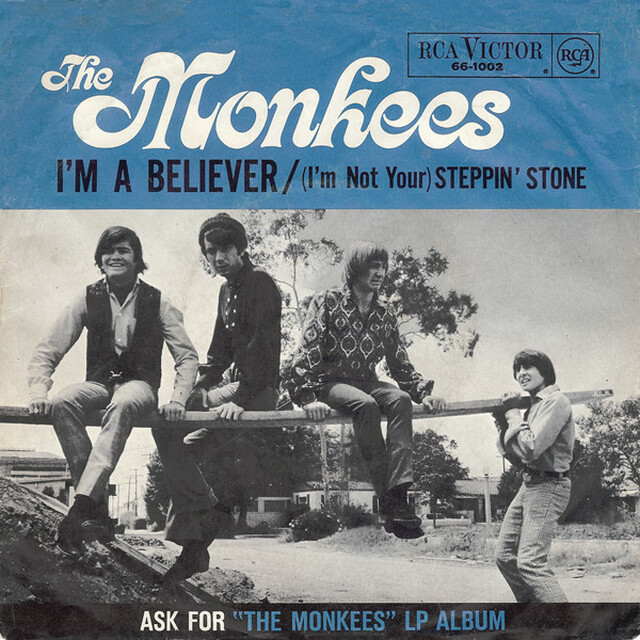

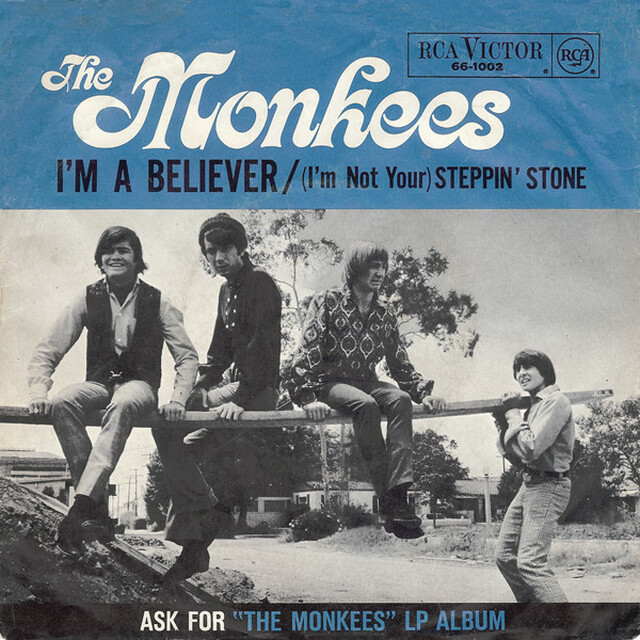

Monkeying Around With My Heart

Let's turn our backs on war and look for romance. Love songs are always popular, and the current Number One hit in the USA is no exception. The upbeat number I'm a Believer by the Monkees has been at the top of the charts since early January, and shows no signs of fading away.

And all this time I thought they were just a fictional band created for a television situation comedy.

Tales of Mars and Venus

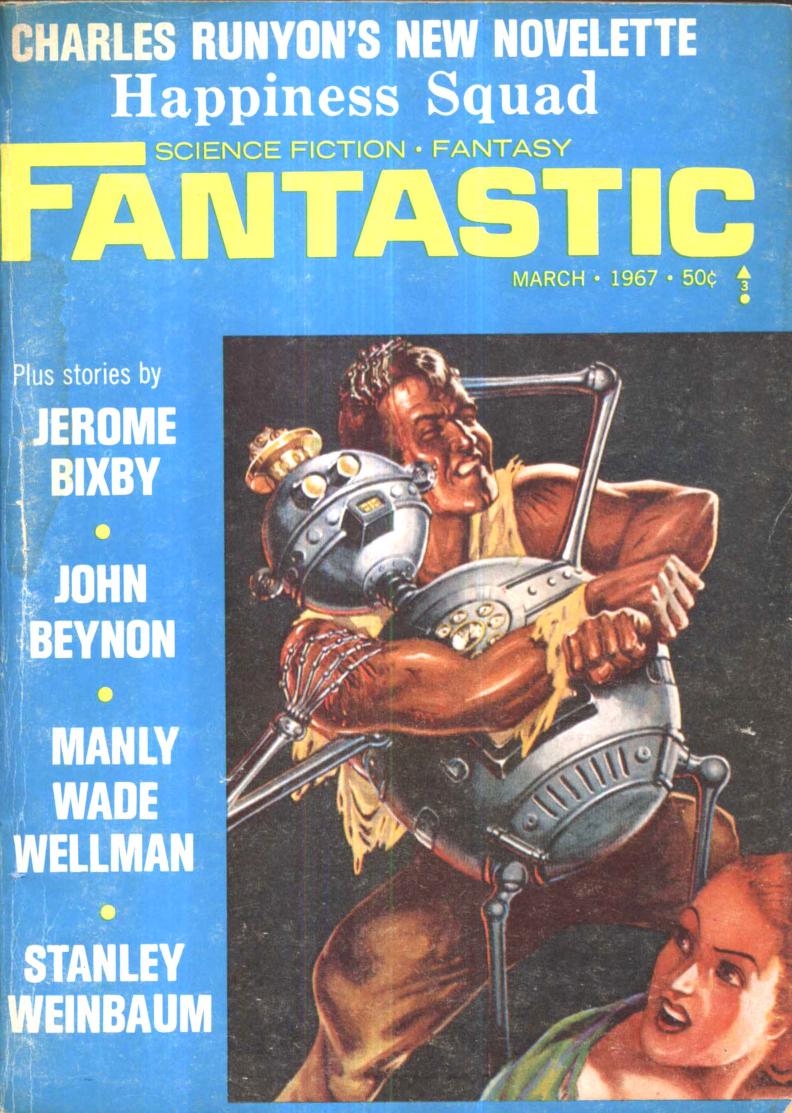

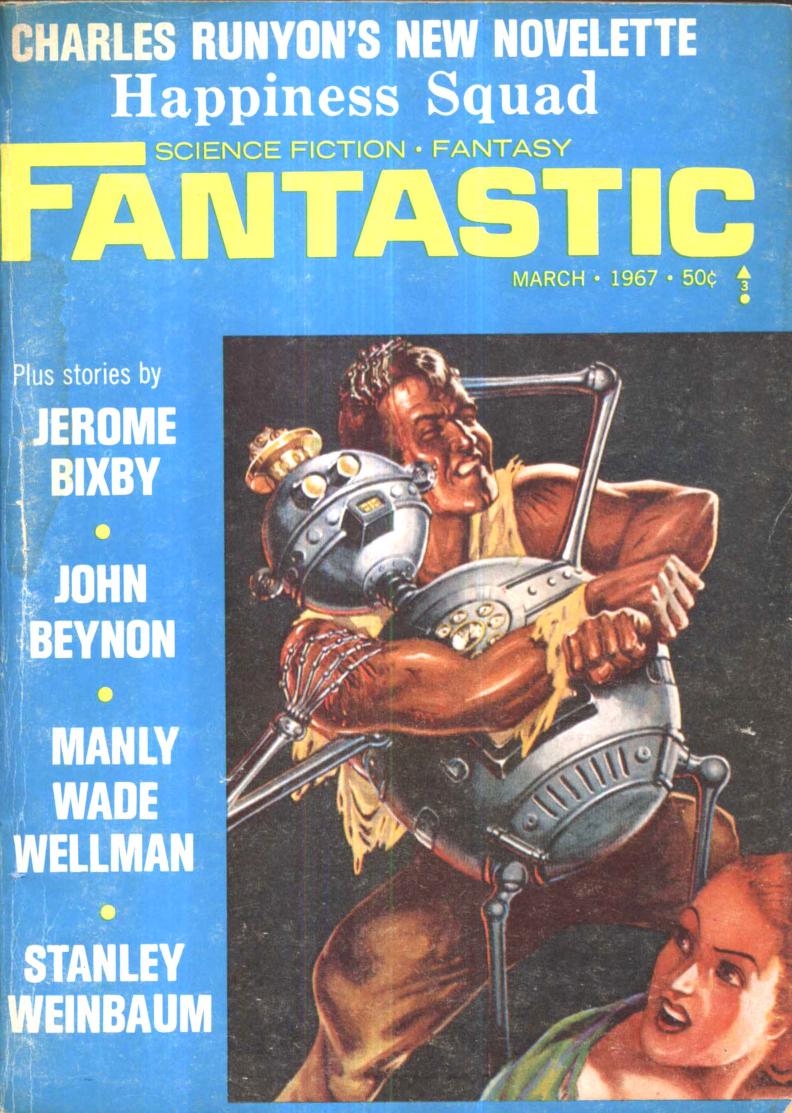

The latest issue of Fantastic is full of stories involving wars, both large and small, as well as amorous relationships between women and men. Sometimes both themes show up in the same yarn.

Cover art by Robert Fuqua.

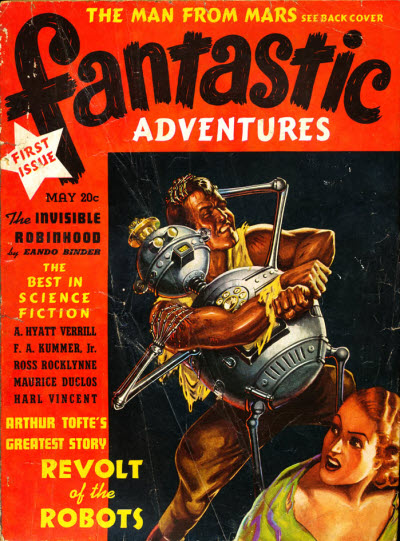

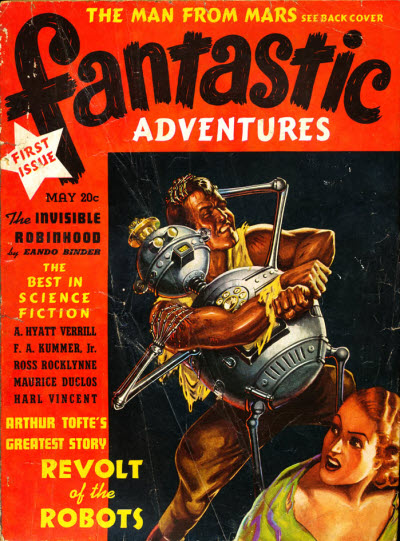

This issue, unsurprisingly, features one new story and a bunch of reprints. The cover illustration is also from an old magazine.

The May 1939 issue of Fantastic Adventures, to be exact.

Happiness Squad, by Charles W. Runyon

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

A personal war meets love gone very bad in the opening of the only original story in the magazine. A man places a timebomb in his wife's flying car, so it will explode during her flight to visit her mother. After this stark beginning, we learn something about this future world, and the man's place in it.

In the tradition of Aldous Huxley's famous novel Brave New World, this is a society bent on eliminating unhappiness through the use of drugs. It has also nearly wiped out the ability of human beings to perform acts of violence on each other, in a way reminiscent of the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange.

In addition to that, it also manipulates memories, in such a way that it can give people completely new identities. The uxoricidal protagonist accidentally discovers that he was once a brilliant plastic surgeon, who transformed an unattractive woman into a raving beauty. The woman, with the help of the man's rival, then altered his memory so that he imagines himself to be her loving husband.

Because of his programmed aversion to violence, the man sabotages all his attempts to kill the woman he blames for ruining his life. (Besides everything else, he also lost the woman he really loves, who had her memory altered in such a way that she now works in a brothel.) Unable to perform the murder himself, he hires one of the very few people who avoided the programming to do the dirty work. (This fellow was one of the rare folks born on Mars who survived a failed colony and escaped to Earth.)

The killer, the victim, and the man who hired him.

There's a twist ending that changes everything we thought we knew. Without giving too much away, I interpret the conclusion as implying yet another reversal, which the author leaves unwritten. I may be reading too much into this, but what remains unsaid is just as powerful as what is made explicit, I believe.

I have a hard time giving a fair rating to this very disturbing story. It's not exactly pleasant to read, but it held my attention from the beginning to the (incomplete?) end. It's nearly impossible to sympathize with any of the characters, even if they're not really responsible for the kind of people they've been manipulated into becoming. The subtle implications of the conclusion may just be in my imagination. In short, I think I like this story more than I should, if that makes any sense at all.

Four stars.

Shifting Seas, by Stanley G. Weinbaum

The April 1937 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this apocalyptic work from the pen of a pioneering author who died much too young.

Cover art by Leo Morey.

Gigantic volcanic explosions and earthquakes rip apart the isthmus of Central America, driving most of the land under the sea. Besides the immediate deaths of millions, this changes the flow of the Gulf Stream, so that much of Europe becomes much colder. The crisis alters political alliances. In particular, war between the United States and a desperate Europe, led by the sea power of the United Kingdom, seems imminent.

Illustration also by Leo Morey.

Besides war, we also have love. The protagonist is an American man engaged to a British woman. The impending conflict threatens to destroy their relationship, until the man comes up with a way to solve the problem without a clash of arms.

The premise is an interesting one, and I liked the way the author considered the political implications of a major change in world climate. The resolution may be a little too simple, and the narrative style a bit old-fashioned, but the story creates a decent sense of wonder.

Three stars.

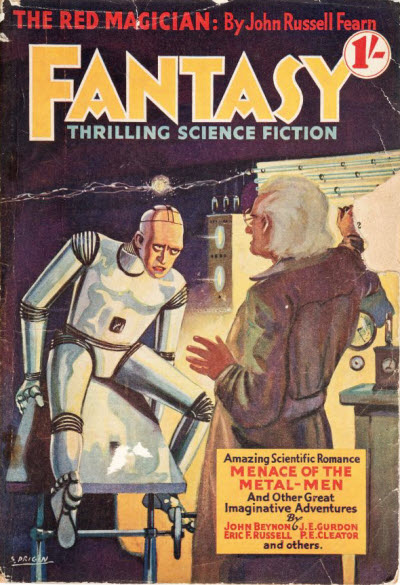

Judson's Annihilator, by John Beynon

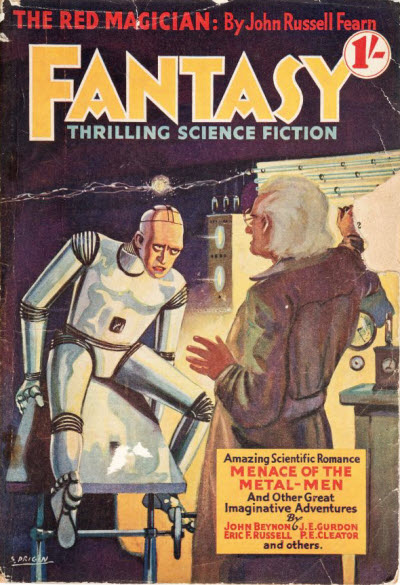

An author now better known as John Wyndham supplies this war story, which first appeared in a British publication under the title Beyond the Screen.

Cover art by Serge Drigin. This issue, number one of only three ever published, is dated 1938, without specifying the month.

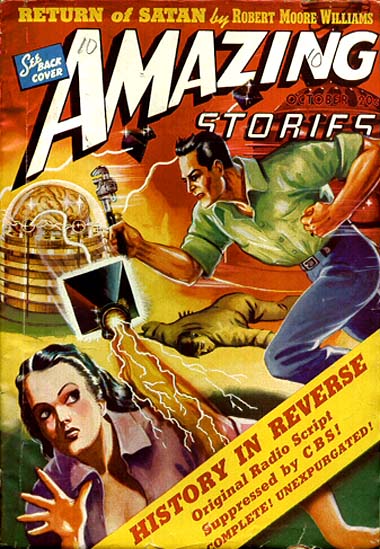

It was quickly reprinted in the October 1939 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Robert Fuqua.

In true Astounding/Analog style, a lone genius invents gizmos producing fields that make anything inside them disappear. When combined German and Italian forces send a huge number of planes to attack England, the devices cause the aircraft to vanish.

Illustration also by Robert Fuqua.

The inventor's sister falls into the field produced by one of the machines and disappears. The hero, in love with her, follows her into it. As the reader suspects by this point, the invention doesn't really destroy what passes through the field, but sends it somewhere else. The place turns out to be an England inhabited by a small number of people living in a primitive way. With the help of a local woman, the hero and his beloved escape from the clutches of the Germans who went through the field.

There's a nice little twist about where they've wound up that is mentioned in passing, but nothing much comes of it. The plot is pretty straightforward once the hero enters the field. I found the imaginary version of World War Two the most interesting part of the story. Other than that, it's a pretty typical science fiction adventure.

Three stars.

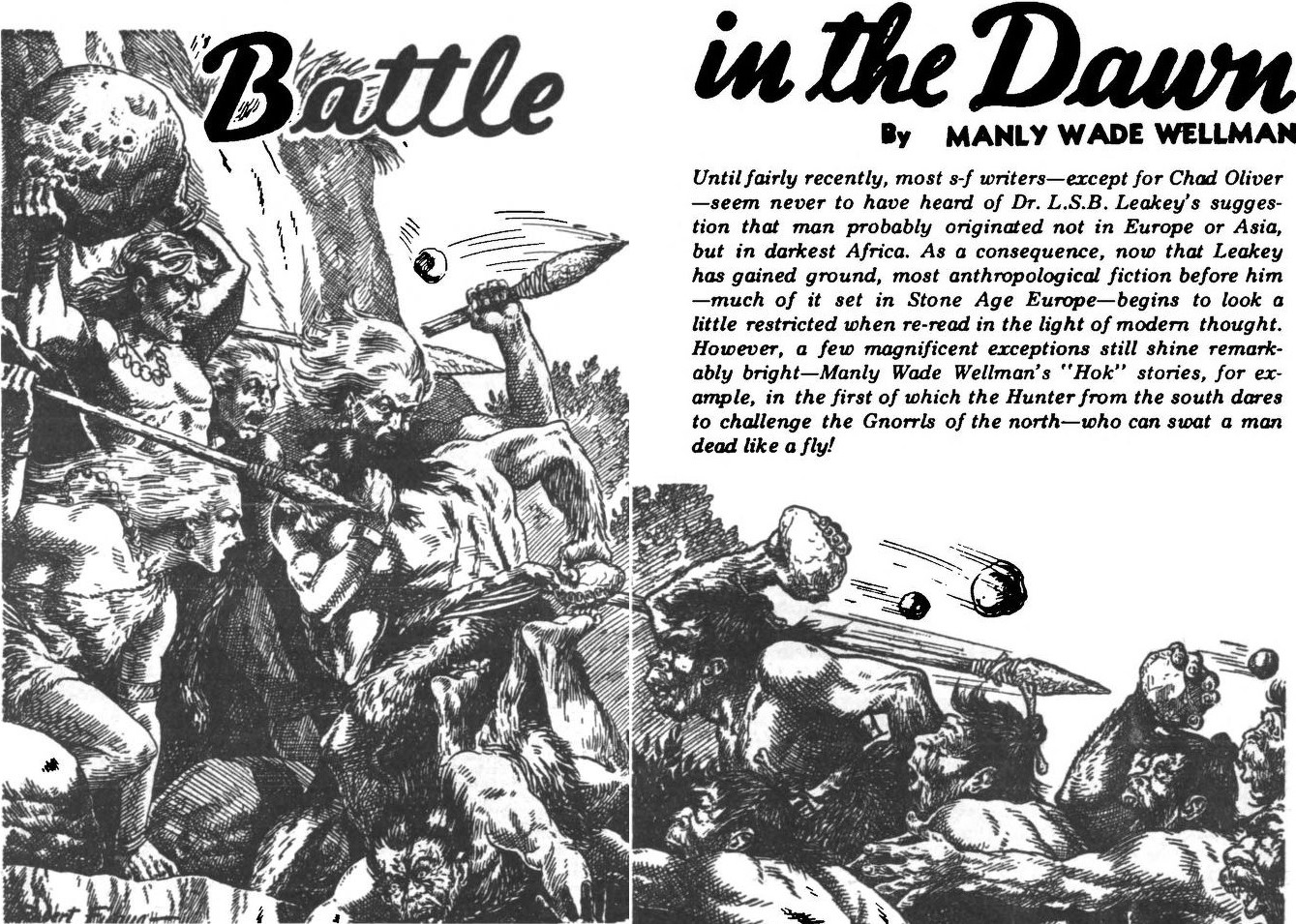

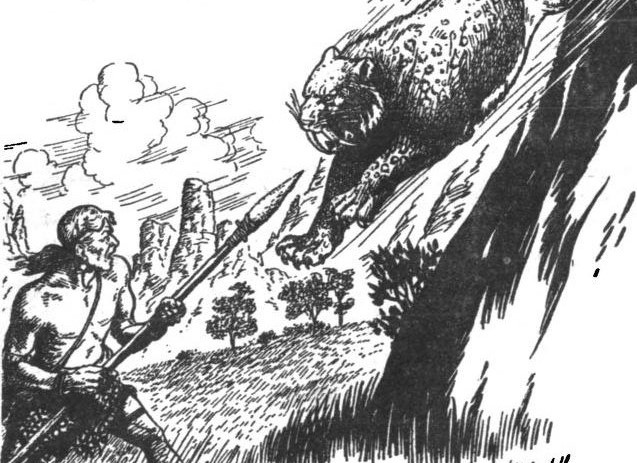

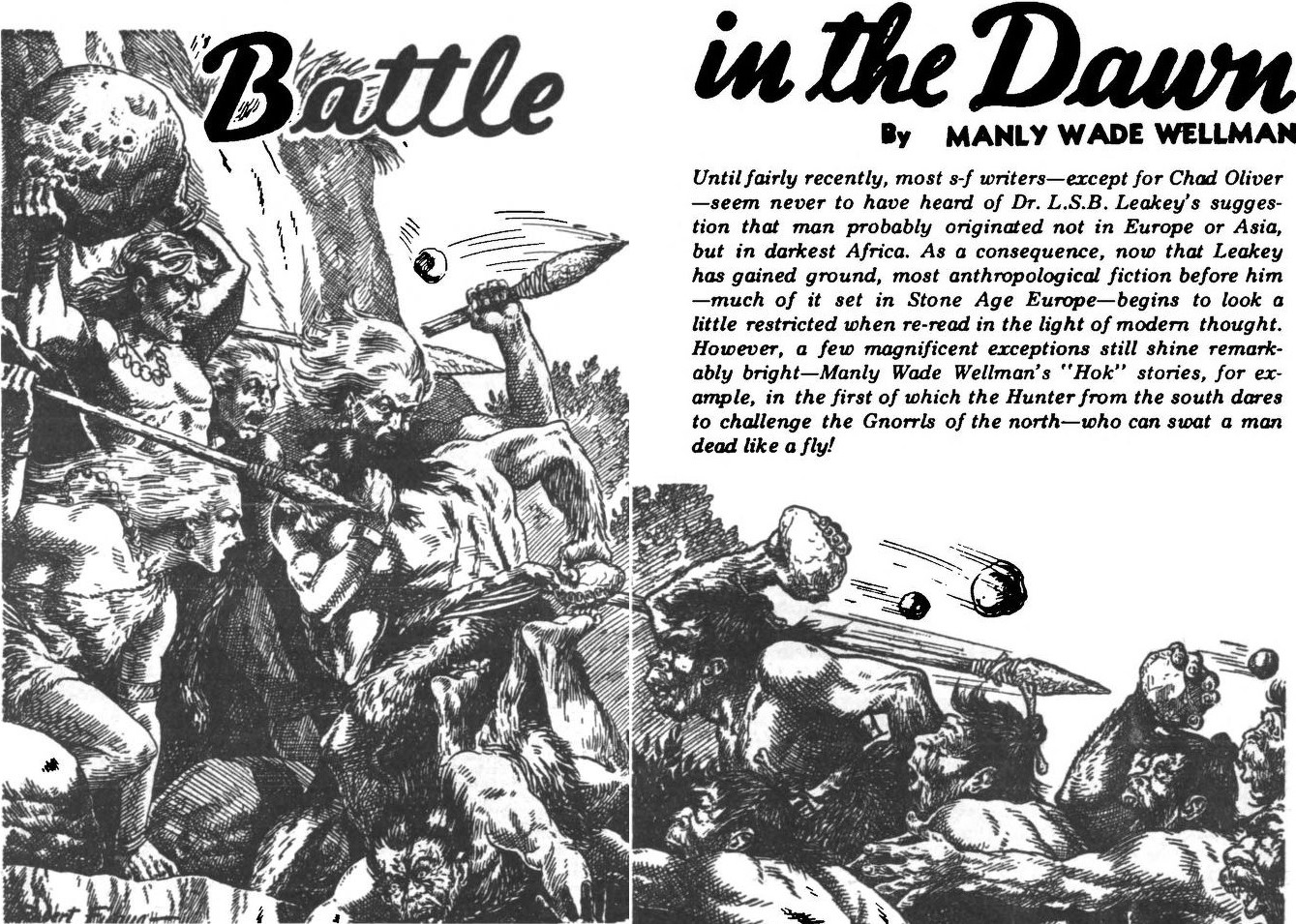

Battle in the Dawn, by Manly Wade Wellman

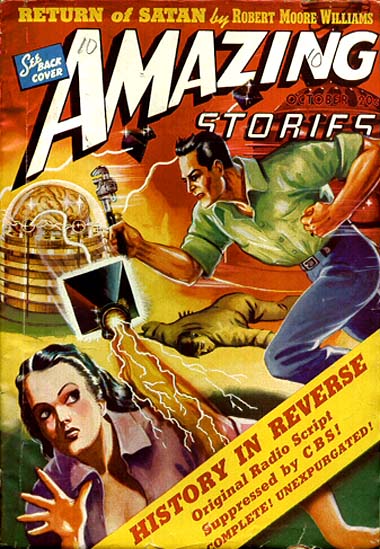

From the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories comes this vision of the remote past.

Cover art by Robert Fuqua again.

Apparently, this is the first of a series of stories about a caveman named Hok. In this tale, his tribe is moving to better hunting grounds when they run into Neanderthals. Contrary to what modern anthropologists think, these are bestial creatures, who attack the group of Homo sapiens and even kill a baby and eat it. Obviously, a war between the two species begins.

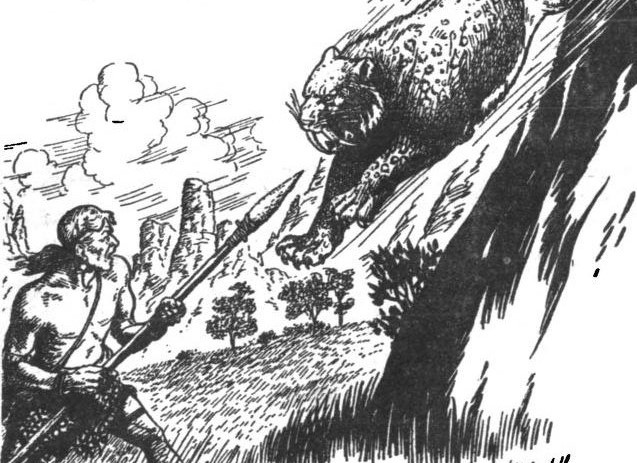

Illustrations also by the ubiquitous Robert Fuqua.

After an initial triumph over the subhumans, Hok steals a woman from a rival tribe of Homo Sapiens, in order to make her his mate. She objects, going so far as to threaten to kill herself if he doesn't let her go. Eventually, the first kiss in history makes the woman fall in love with her captor, and the two tribes unite against the Neanderthals.

Not to mention other challenges.

With nearly three decades of hindsight, it's easy to dismiss this story as a very inaccurate portrait of prehistory. It might better be thought of as a sword-and-sorcery yarn, without swords and without sorcery. The Neanderthals are monsters, the hero is a brave warrior with a beautiful woman to win, and so forth. As such, it's a fair example of the form.

Three stars.

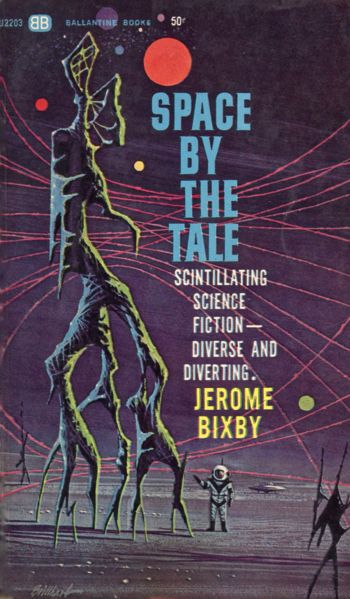

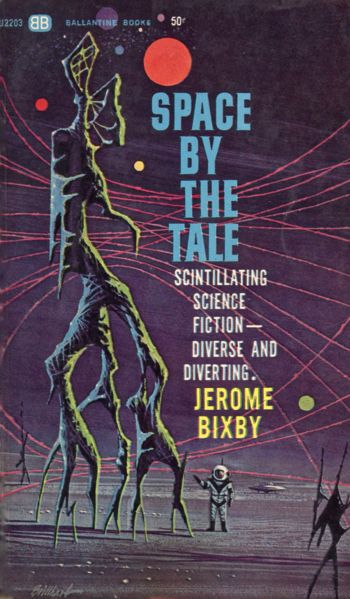

The Draw, by Jerome Bixby

The March 1954 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this tale of the Old West, where war often consisted of one man against another.

Cover art by Clarence Doore.

You may have already seen it in a paperback collection of the author's stories that came out a few years ago.

Cover art by Ralph Brillhart.

An onery teenager — we'd call him a juvenile delinquent these days — is an excellent marksman, but not good at all when it comes to pulling his pistol from his holster. This is the only factor that keeps him from becoming an infamous killer.

Illustrations by William Ashman.

Through sheer force of will, he develops the telekinetic ability to instantaneously transport his gun to his hand, making him the deadliest gunman around. After terrorizing the local townsfolk, he challenges the sheriff to a gunfight. As you'd expect, things don't go well for him.

A scene from Gunsmoke?

I don't have a lot to say about this story. The ending is somewhat anticlimactic, but there's nothing particularly wrong with it. The usual Western clichés are present, which may be inevitable.

Three stars.

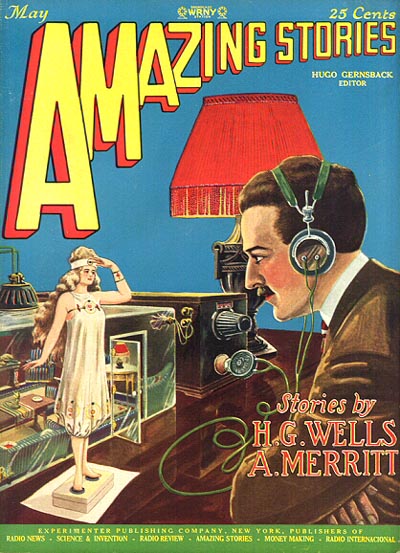

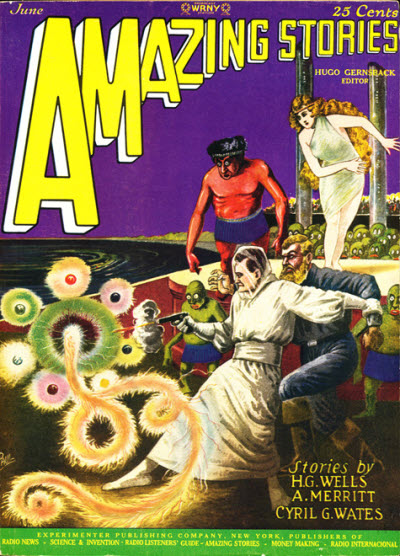

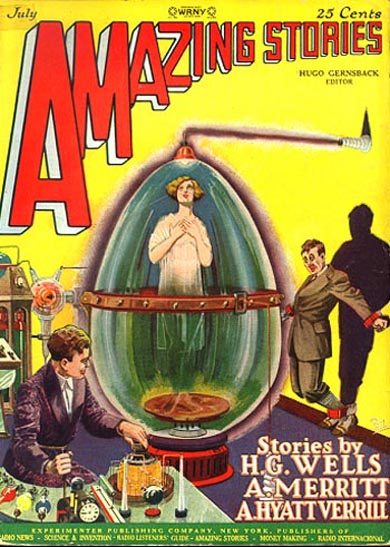

Masters of Fantasy: A. Merritt Illustrated, by Anonymous

The magazine ends with a few drawings by Frank R. Paul that accompanied a reprint of Abraham Merritt's 1919 fantasy novel The Moon Pool, which was serialized in Amazing Stories in the May, June, and July 1927 issues.

I guess this is the Moon Pool.

All cover art by Frank R. Paul as well.

I didn't notice the frog people at first.

I'm guessing this is a scene from The Moon Pool.

Is she doing the Twist?

Caution! Mad Scientist at Work!

What can I say? Three stars.

Fighting for Something to Love

In this magazine full of love and war, the stories were fair. Not that great, not that bad. I predict that Runyon's new novelette is going to produce strong reactions, both positive and negative. The reprints are likely to be less controversial.

As for the choice between the two great themes I've noted, it seems like an easy one.

Somebody came up with this catchy slogan a couple of years ago, and now you can get it on a poster.

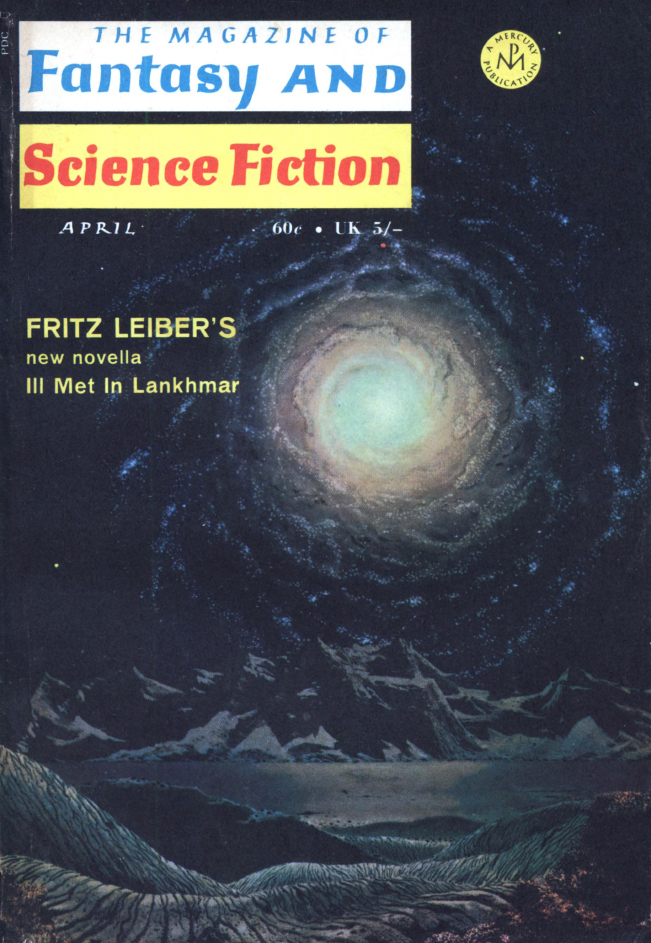

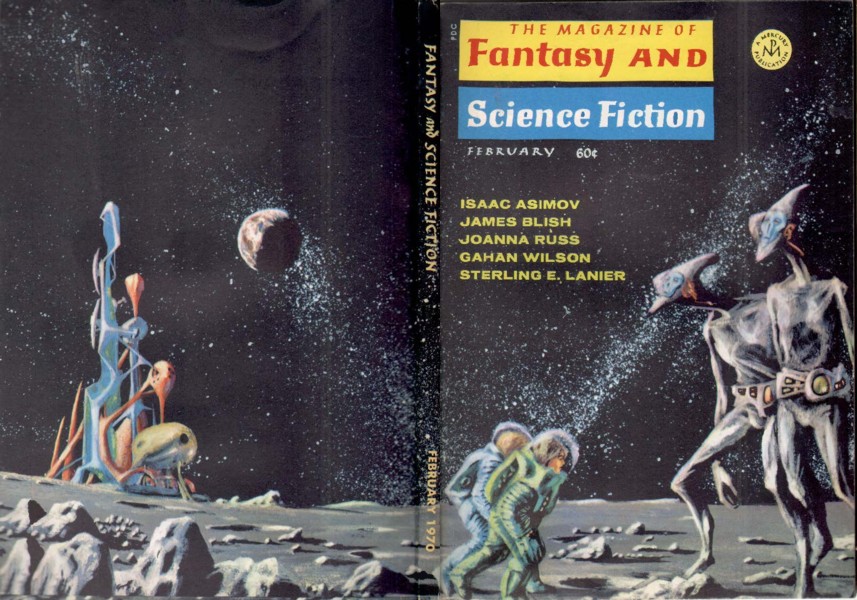

![[March 20, 1970] Here comes the sun (April 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700320fsfcover-651x372.jpg)

![[January 20, 1970] Jolly good Ffelowes (February 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700120fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 24, 1969] Flying and dragging (September 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690820fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1967] Transitions (May 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IF-Cover-1967-05-672x372.jpg)

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)