[Today is the last day you can sign up for next year's Worldcon if you want to be able to nominate Hugo candidates! Sign up now!]

by Gideon Marcus

An argument for free trade?

Yesterday, Europe got a bit freer. The nations of Austria, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom–along with associate member, Finland, the constituents of the Europen Free Trade Association–removed all tarrifs on industrial goods sold between them. These countries comprise Europe's "Outer Seven", in contrast to the "Inner Six" of the European Economic Community. With this move, EFTA's economies may get a competitive boost against the traditional European powerhouses (France, West Germany, Benelux, and Italy).

The SF mag Analog is better suited to the EEC than EFTA. With editor John Campbell at the helm, who personally reads and approves every item chosen from the slush pile, and who has a distinctive style (to the say the least), the magazine has really gotten itself into a rut. Sometimes it manages to be good, but more often, as with this month, it's deadly dully. Read on, and you'll see what I mean.

The issue at hand

by Chesley Bonestell

Supernova, by Poul Anderson

by Kelly Freas

David Falkayn, protegé of Nicholas van Rijn, returns in yet another astronomically interesting but utterly dull adventure. This time, callow human Falkayn, and his trader team comprising the pacifist buddhist saurian, Adzel, the foul-mouthed racoon, Chee Lan, and the computer, Muddlehead, have visited a world about to be blasted by a nearby supernova. The planet, at about a Year 2000 level of technology, is riven into several regional powers, and a system-wide crime syndicate has nation-like power.

Falkayn is struggling with determining who their team should work with to build a planetary shield when the decision is taken out of his hands: Chee Lan is abducted by the system's equivalent of the mob. Falkayn's solution to his dilemma is supposed to be clever, but it feels obvious and uninspired.

Two stars.

A Criminal Act, by Harry Harrison

by Kelly Freas

Here's a piece inspired by the same Malthusian nightmare as the author's hit, Make Room, Make room. A fellow and his wife have had three kids, one more than the law allows. As a result, a kill-happy citizen is legally allowed to try to bump the dad off. It's a duel to the death, either result of which will keep the population stable.

Bob Sheckley could have made this work. Maybe. In another magazine.

Two stars.

Bring 'Em Back Alive!, by Lyle R. Hamilton

The nonfiction article this month is about wind tunnels, heat shields, and retrorockets. Not a bad topic, but Hamilton's overly breezy style doesn't quite work.

Three stars.

Amazon Planet (Part 2 of 3), by Mack Reynolds

by Kelly Freas

Last time around, author Reynolds took us back to the world of the United Planets, a loose galactic confederation of humans in which each planet is allowed whatever government, culture, demographics it likes. This time, the planet is Amazonia, ruled by women and with the cultural iconography of the famed Greek warrior women.

Guy Thomas was a mild-mannered trade entrepreneur hoping to stoke an iridium/columbum trade between Amazonia and Avalon. But at the end of the last installment, we discovered he was actually a secret agent. In Part 2, we find out he's a UP spy, sent when a man from Amazonia made an unprecedented escape from the planet and pleaded for refugee status. It seems there's a widespread masculine revolutionary movement.

Unfortunately for Thomas, he is quickly captured by the technologically superior Amazons and made to reveal his true identity: he is none other than Ronny Bronston, part of the mysterious Section G, whose explicit purpose is to topple regressive governments–in flagrant violation of the Federation's constitution. Under truth drugs, Bronston spills the beans. But before he can give further info, he is rescued by a member of his original escort party, a female soldier who has taken a shine to him.

Out of the frying pan and into the fire!

My nephew continues to rave about this series, whereas I find it mostly an excuse to discuss political theory interspersed with some boilerplate action sequences (which, to be fair, Reynolds has made a good career of).

Barely three stars and sinking.

The Old Shill Game, by H. B. Fyfe

by Kelly Freas

A robovendor is programmed to have an edge on his daily rounds at the concourse. With the aid of a team of robotic shills, it attracts the attentions of human commuters and makes a killing. Thus ensues a war between the robovendor's programming team and that of their competitors, each iteration making the android vending machine a bit smarter.

The road to Mike from The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is paved with capitalism.

There's a good idea here, but the execution is a bit muddled and the whole thing just not very satisfying. Two stars.

The Last Command, by Keith Laumer

by Kelly Freas

From one sapient robot to another: Keith Laumer returns with his answer to Saberhagen's Berserker series, only Laumer's Bolos are tanks rather than ships, and they apparently used to work for people rather than against them.

In this installment, a long-dead machine comes to life deep underground, nearly a century after its last conflict. Certain that it has been imprisoned by the enemy, it roars to life, slowly making its way toward a city that has sprouted since its deactivation. An old veteran of the old battle thinks he has the key to stopping this indestructible weapon of war.

It's a bit less polished than previous entries in the series, but I found the end touching.

Three stars.

Doing the math

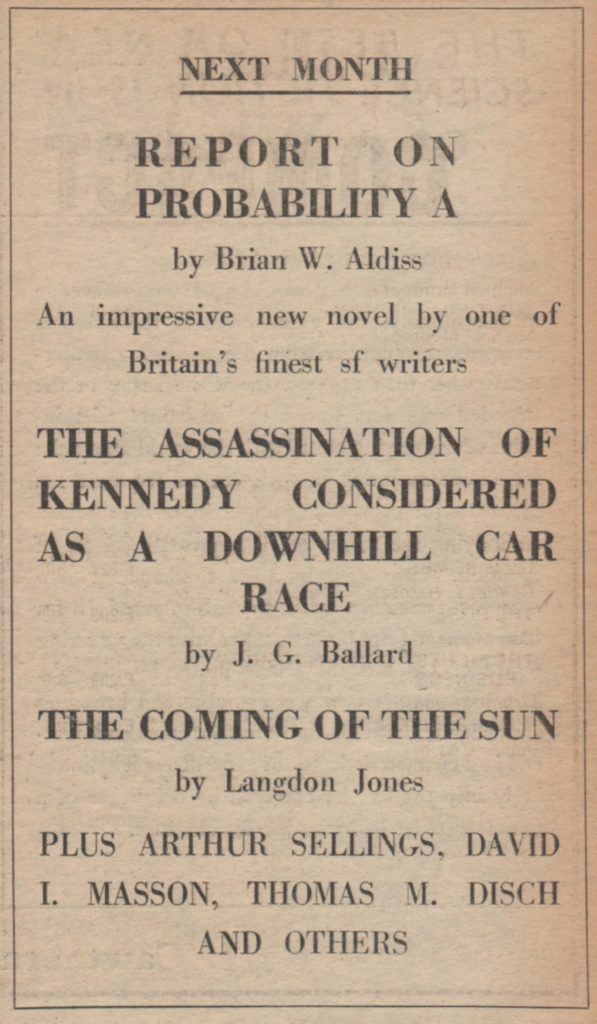

Running the Star-o-vac, I find Analog scored just 2.5 stars–the worst of the month! But this has been kind of a lousy month in general, so it's not certain that open trade is the answer. After all, the British mags, New Worlds (3.3), and Science Fantasy (2.9), are rumored to be on the edge of extinction. Fantastic (2.6) wasn't good this month, even with decades of reprints available. IF (2.8) was thoroughly mediocre. And while I liked Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.2), no one else seems to be enjoying the new serial.

On the other hand, there was exactly one story by a woman this month, and it was one of the best ones. Maybe, instead of free trade between the current magazine contributors, we need a campaign to tap the as yet fallow resource: women writers.

Crazy, I know, but it's a thought.

[Today is the last day you can sign up for next year's Worldcon if you want to be able to nominate Hugo candidates! Sign up now!]

![[December 31, 1966] Barriers to quality (January 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661231cover-672x372.jpg)

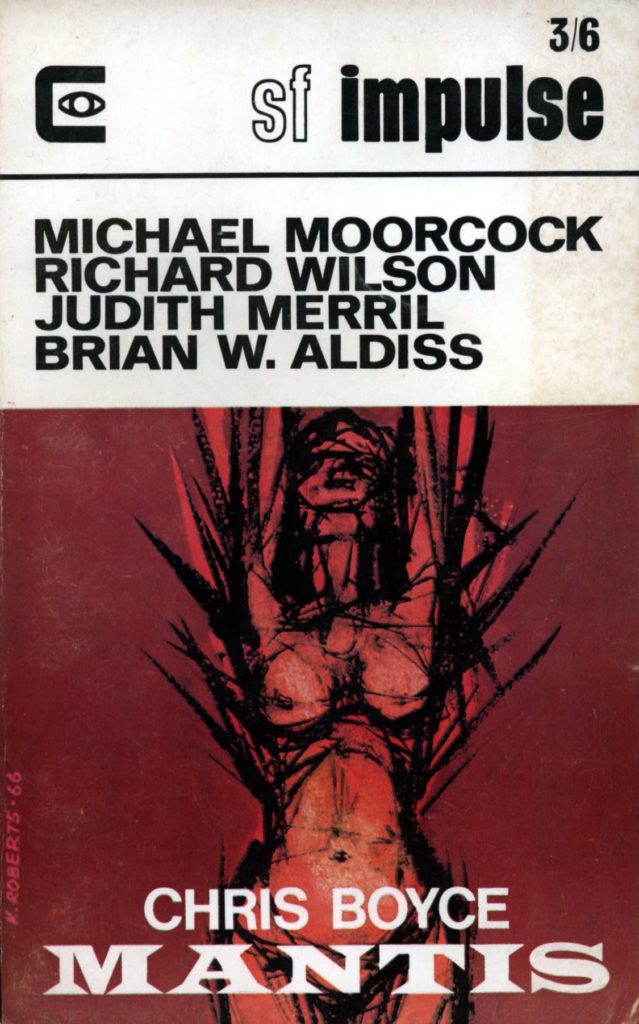

![[December 28, 1966] Ice Worlds, Telepathic Martian Mice and Echoes (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, January 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/New-Worlds-Impulse-Jan-67-1-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[December 26, 1966] Harvesting the Starfields (1966's Galactic Stars!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661226plough-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1966] Unquiet on the Romulan Front (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Balance of Terror")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661224title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 22, 1966] Who's In Charge Here? (<i>The Monitors</i> by Keith Laumer and <I>The Nevermore Affair</i> by Kate Wilhelm)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661222covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)

![[December 18, 1966] The Manchurian Colonel: <i>Space Patrol Orion</i>, Episode 7: "Invasion"](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Raumpatrouille-Orion_1499343747406665-672x372.jpg)

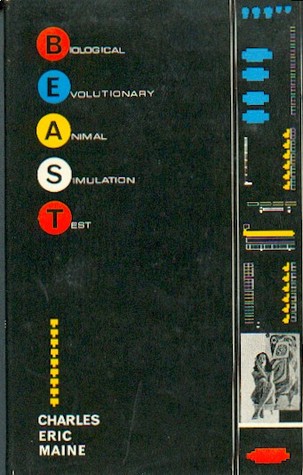

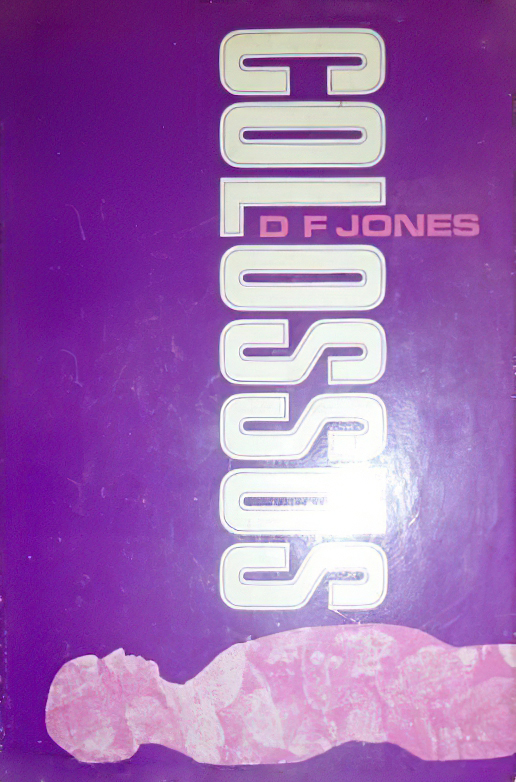

![[December 16, 1966] The God Slayers (two computer-themed novels)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661216covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 14, 1966] (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Conscience of the King)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661214title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 12, 1966] An Explosive Ending (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Power Of The Daleks [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661212assemblyline-672x372.jpg)