by Gideon Marcus

Boo!

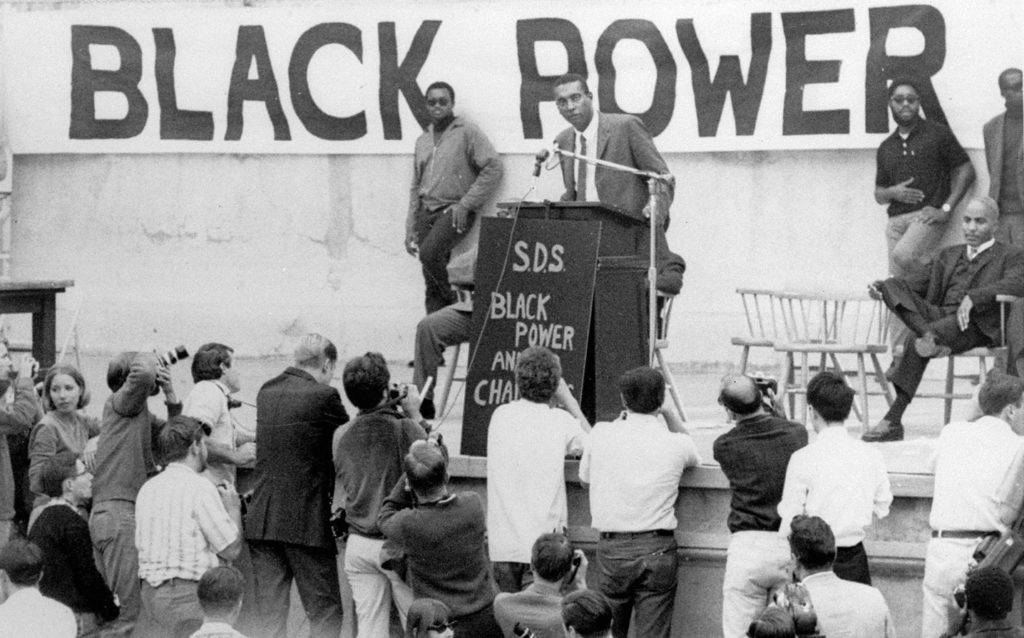

It's a scary world out there. If ever there was an appropriate time to be reminded of it, it's today, Halloween. These days, it's not the supernatural or the spooky that frightens the bejeezus out of us (though UFO sightings are at a record high). No, it's real-world issues like the ongoing, escalating war in Vietnam. Thousands of our boys have died over there, and there's no end in sight. The other day, Stokely Carmichael, head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, said he had no intention of fighting were he to be drafted. He's currently living with the Sword of Damocles of his latest physical fitness exam — will he be judged fit for duty? Is prison preferable to serving in an unjust war?

There are fears on the domestic front, too. Grocery prices have spiraled to ridiculous levels, and an organized army of housewives has picketed the stores in at least 15 cities across America. Can they effect change before basic foods get too expensive too afford?

I think all of this existential dread is why folks turn to fiction. I've now had several fans of my Kitra series note their appreciation that, while they find Kitra's adventures riveting, they take comfort in knowing that she and her crew will come out safe in the end. It's a reassurance they aren't finding in real life

I felt similarly reading the latest issue of Analog. Sometimes science fiction paints grim futures, even seeming to relish in the despondence of the characters who inhabit them (q.v. Harrison's overpopulation nightmare, Make Room! Make Room!). Such works are important. Cautionary tales are important. They show us potentialities to avoid. They challenge us to think. But sometimes, you just want an interesting story where you know things will all work out. Analog's editor John Campbell has given us two quite good ones this month (and some other stuff).

by Kelly Freas

Yay!

Quarantine World, by Murray Leinster

by Kelly Freas

Dr. Calhoun of the Med Service has reason to be suspicious. The planet Lanke is ostensibly perfectly healthy, yet the government is going out of its way to hide something from him. Moreover, Lanke's politicians are keenly interested in the public health specifically for its insuring the bottom line of their economy. It is thus with appropriate shock to all concerned that a plague-infested person, obviously an off-worlder, crashes Calhoun's reception. More shocking — the Lanke government insists Calhoun have nothing to do with the individual, who is shot by the authorities. When he performs a cursory examination of the corpse, he is summarily ejected from the planet.

Whereupon he contracts the deadly disease, and his trusty tormal, the antibodies-producing cat/monkey called Murgatroyd, is unable to synthesize a cure! Calhoun's only clue (and hope!) is the existence of a failed colony on the nearby planet of Delhi. Perhaps there he can solve the mystery of his illness before he…and the population of Linke…succumbs to it.

Murray Leinster is often called the dean of science fiction. He's been writing for decades, and sadly, the tape is starting to wear a little thin. He pads out his work a lot, and his characters mostly sound alike. There is a strange, juvenile character to his writing that feels out of place in Analog. Honestly, it may be less a matter of literary senility, and more that of bilking an extra hundred bucks from Campbell for the extra verbiage; writers are paid by the word, after all.

But.

It's a good story, highlighting several interesting social issues (capitalism uber alles, the treatment of criminals and political dissidents, the role of medicine). It's a great universe, one I've drawn inspiration from for my Kitra books. And Murgatroyd is an absolute joy to read about.

So, three stars.

Facts to Fit the Theory, by Christopher Anvil

by Kelly Freas

The human colony of Cyrene IV is about to be invaded by the rapacious Stath. Yet the Cyrenicans refuse to join the Terran Federation, which would protect them under the auspices of a non-aggression pact with the Stath. All attempts to coerce an application to the Federation are thwarted by increasingly improbable events, all of which point to some kind of religio-psychic interference on the part of the colonists.

Then the Stath arrive. Their attemps to be mean and nasty are also countered by freak occurrences, up to and including a planetary hurricane. They leave, tail between their legs. The human military officers are admonished to write up a full report, but to explain the chronology without invoking ESP.

Could there be a more archetypical Chris Anvil Analog story?

- Tongue-in-cheek? Check.

- Humans come out ahead? Check.

- Prominent figuring of psionics? Check.

- Authorities are stupid for not acknowleding the existence of psionics? Check.

- The Traveler sick of stories like this? Check and Check.

Two stars because it's readable, but please, no more. I beg you.

Dimensions, Anyone?, by John D. Clark, Ph.D.

A fascinating if abstruse piece from Dr. Clark. It's about the importance of a matching set of physical dimensions for rendering useful measurements. Forget the "English" system, and even the metric system isn't truly universal. Clark offers up one of his own, while describing the history of the ones we currently use.

Much denser than Asimov's stuff, but it was in my wheelhouse. Four stars.

Letter from a Higher Critic, by Stewart Robb

by Kelly Freas

In which folks in the 22nd Century, having lost most historical sources of the 19th and 20th Century, deem that World War 2 is too improbable to have occurred as recounted. The primary objection is that the names of all of the major players, from Roosevelt to Churchill to Adolph Hitler to Stalin, are too on-the-nose to represent real people.

Very slight stuff. Blink and you'll miss it. Read and you'll forget it.

Two stars.

Too Many Magicians (Part 4 of 4), by Randall Garrett

by John Schoenherr

And now we come to the end, both of the magazine, and of this most promising murder mystery serial from Randall Garrett. Good luck putting it down — it is a rollercoaster from the opening sequence, in which Lord D'Arcy has just dived into the Thames to rescue a bewitched woman, to the final scene, in which Chief Investigator for the Duke of Normandy identifies the culprit from among nine suspects.

It's a well-drawn whodunnit, weakened only by its separation into four parts (which the assured novelization will fix). The solution is plausible and (mostly) independently deducible. The guilty party makes sense. I appreciated the quantum mechanics element of the case, too; it is impossible to observe matters without affecting them. It makes this particular Lord D'arcy case quite dynamic. I also noted the homage to Twelve Angry Men in one scene.

Garrett has gotten much better at handling woman characters: Mary, Dowager Duchess of Cumberland, and Demoiselle Tia Einzig are nicely realized and pivotal players. Hard to believe this is the same fellow who wrote Queen Bee. For the same magazine!

So, five stars for this segment, four and a half for the story as a whole, and I won't be surprised if this gets a Hugo nod in New York next year!

Summing up: Two tricks and three treats

Setting aside the Anvil and the Robb, Analog really delivered the goods this month, providing a bubble of reassuring entertainment in a frightening era. Clocking in at 3.4 stars, it surpasses or ties with the other magazines this month except for the exceptional Science-Fantasy/Impulse (3.7 stars).

Technically, Fantastic (3.5 stars) was also better, but given that it was largely reprints, I don't know that it's a fair comparison. Of the all-new material mags, the order goes Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.4), New Worlds (3.1), IF (3), and Worlds of Tomorrow (2.3).

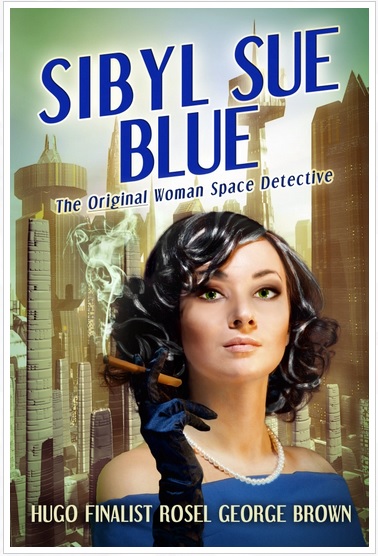

It was actually a great month for fiction. One could fill three whole magazines with all the four and five star stuff. Sadly, there was not a single woman-penned piece of fiction published in a pro mag with a November 1966 date.

And with that, the unpleasant real world intrudes again. Ah well. I managed to avoid it for most of an article. Maybe next month will bring happier news on this front.

[Actually, there's happier news right now! Sirena, the second book in The Kitra Saga, has been a smash hit, and I think you'll dig it, too. Buy a copy…you'll be supporting me and getting a great read at the same time!]

![[October 31, 1966] Respite from the horror (November 1966 <i>Analog Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661031cover-355x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1966] Return to Base (October 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 31, 1966] Dimmed lights (August 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660731cover-672x372.jpg)