by Gideon Marcus

My World and Welcome to It

Have you ever found that if you read too much Harlan Ellison, you end up sounding like the guy? That same glib, hip, outraged polemic dripping with occasional yiddish and modisms. It's cool for a while, but it ultimately gets a little tiresome.

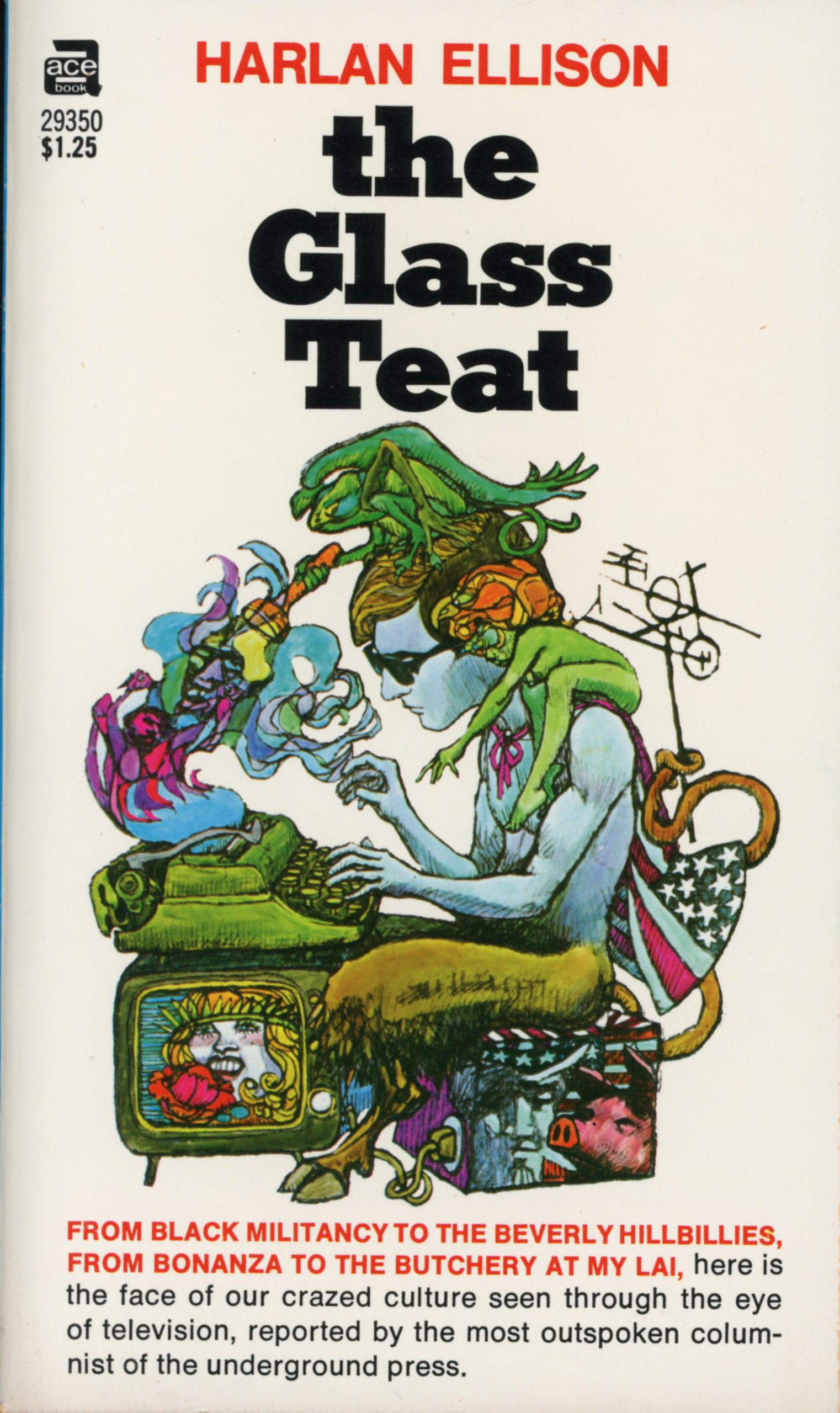

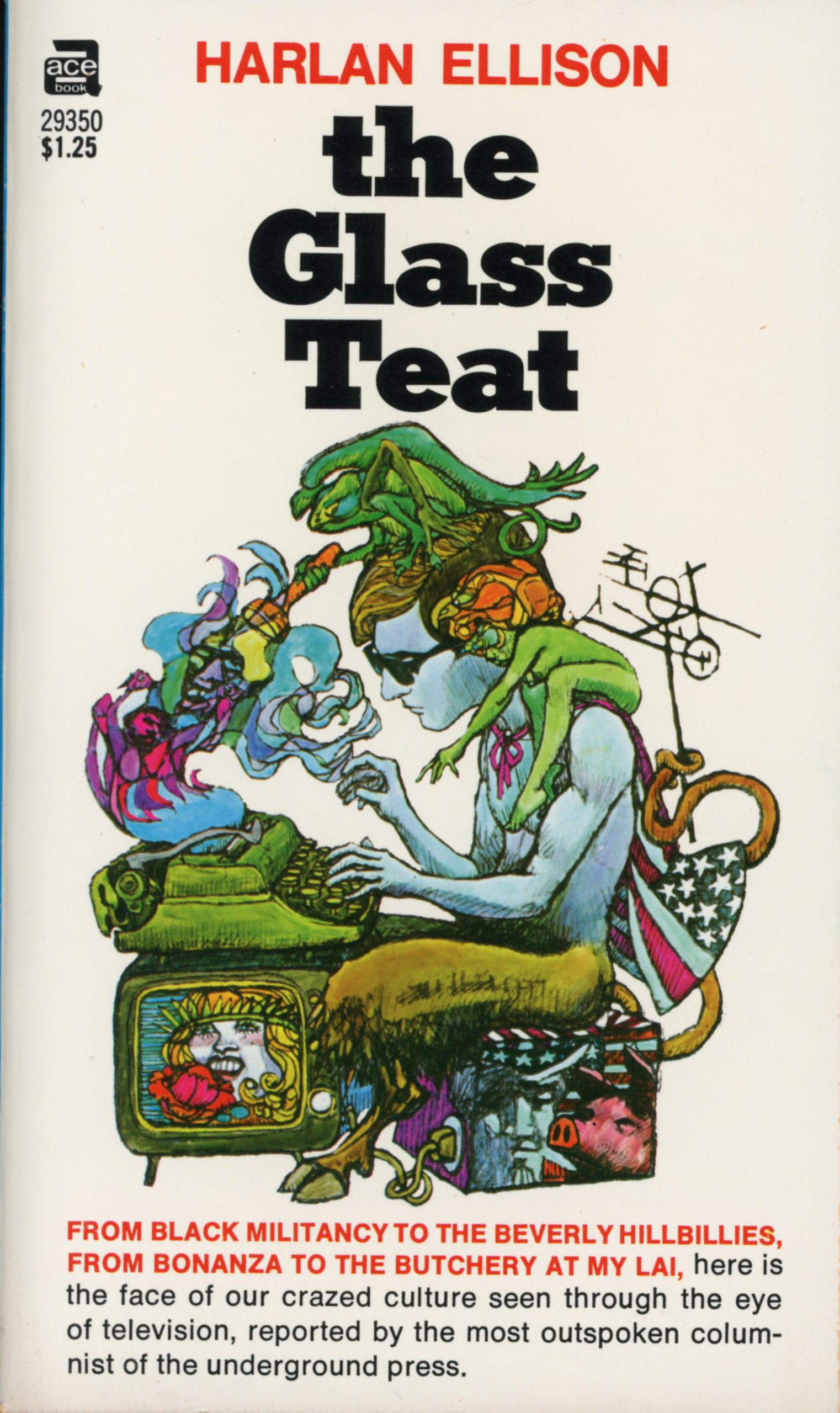

That's why it's a good idea, kiddies, to sample his latest collection, The Glass Teat, a little at a time. Otherwise, you might find yourself with acid in the belly and fire at your typing fingers.

Unlike the Ellison books we've reviewed before here at the Journey, Teat is a wholly unique animal—a collection of articles Harlan wrote for The Los Angeles Free Press (the "Freep") as its TV columnist from September 1968 to January 1970. For the most part, these are not reviews; Harlan was not hired as a critic of individual shows, but the whole small screen zeitgeist. And because the subject that most interests Harlan (just ahead of skirts and social justice) is Harlan, the column serves as a kind of memoir, the travel diary of a TV writer. Hey, write what you know, right?

Interestingly, though I consider myself something of an Ellison devotee (it's a love-hate relationship, but no one can argue the fellow can't compose), I found out about his latest opus in a roundabout fashion. Dig, I was reading the June 1970 issue of Yandro, wherein I found a delightful column by Liz Fishman. It's worth reading—you can write the Coulsons to see if they can get you a back issue, assuming the mimeo stencils and their cantankerous Gestetner is up for another run.

Long story short, after being accosted by a lech who puts Laugh-In's Tyrone F. Horneigh to shame, Liz was saved by a sunny "Matisse painting come to life". They got along just fine until said savior noticed what Liz was reading. It was "sho-nuff a dirty book." That is to say, it was by Ellison, and it had the typical blue phrases that punctuate his writing. The kind of shit you'd never find in my work.

Well, upon learning about Harlan's new book and its unusual nature, I scoured the bookstores of San Diego and managed to come up with a used, hardly touched, copy. Its spine was as smooth as a chiropractor's nightmare. As a result, I didn't get much off the cover price, but I don't mind supporting local business.

Land of the Giants

Cover by Leo and Diane Dillon

So open the cover, and what have we got?

Continue reading [August 4, 1970] Through the Wasteland (Harlan Ellison's the Glass Teat) →

![[August 6, 1970] A Spooky Spook: <i>Larry Brent</i> by Dan Shocker](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/sgk_na_019-390x372.jpg)

![[August 4, 1970] Through the Wasteland (Harlan Ellison's <i>the Glass Teat</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700804teatcover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1970] Fimbulsommer (September-October 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/IF-1970-09-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The Nixons participating in Earth Day.

The Nixons participating in Earth Day. Suggested by “Fimbulsommer.” Art by Gaughan.

Suggested by “Fimbulsommer.” Art by Gaughan.![[July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28,1970] Cinemascope: Cry Me A River (Cry of the Banshee) and Games in Goatskin (Dionysus in ‘69)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700728posters-492x372.jpg)

![[July 26, 1970] "The Hearts of Men" and Women (June and July "Gay Pride" Protests)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Screenshot-2025-07-23-at-12.41.34 AM-e1753269732819-542x372.png)

![[July 24, 1970] They’ve All Come To Look For America (<i>Green Lantern co-starring Green Arrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/GAGL8-672x372.jpg)

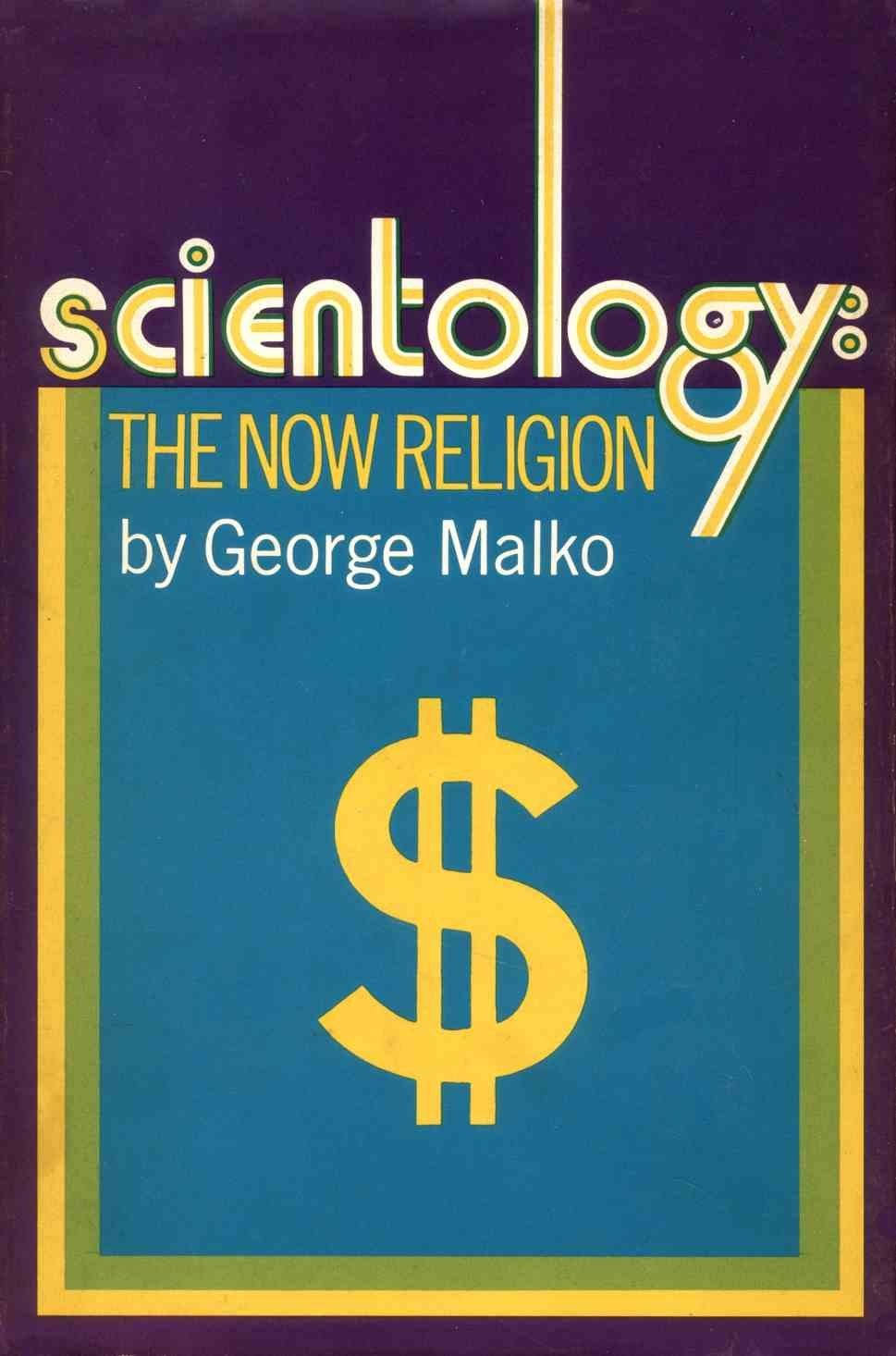

![[July 22, 1970] Solace for Your Trillion-Year-Old Spirit (George Malko's <i>Scientology: The Now Religion</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Scientology-672x372.png)

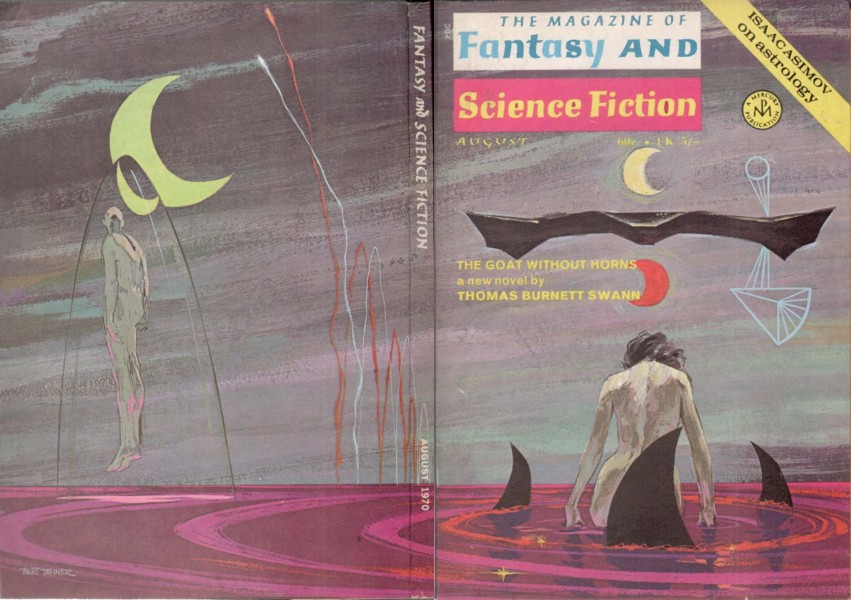

![[July 20, 1970] The Goat without Horns…among other things (August 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700720fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 19, 1970] Dips in road (<i>Maze of Death</i>, <i>The Eternal Champion</i>…and others—July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700719covers-672x372.jpg)