by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

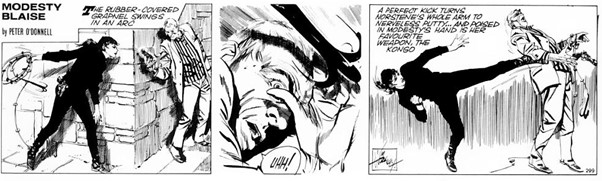

Never let it be said that Science Fiction is always lightweight stuff. Both magazines are tackling big issues this month.

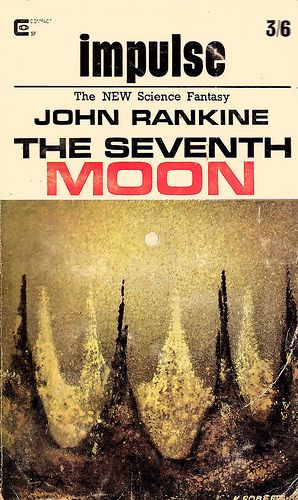

We’re back to fuzzy covers in this month's Impulse – don’t forget, “The NEW Science Fantasy”. It’s OK but not the best. It’s another Keith Roberts, more of which in a minute.

The Editorial this month has the Editor Kyril still meditating over the genre. Readers still like stories about other humans, he suggests – it is rare for humans to like stories that are truly alien – presumably a response to the Merril story started last month and concluding in this. (More later.)

To this month’s actual stories.

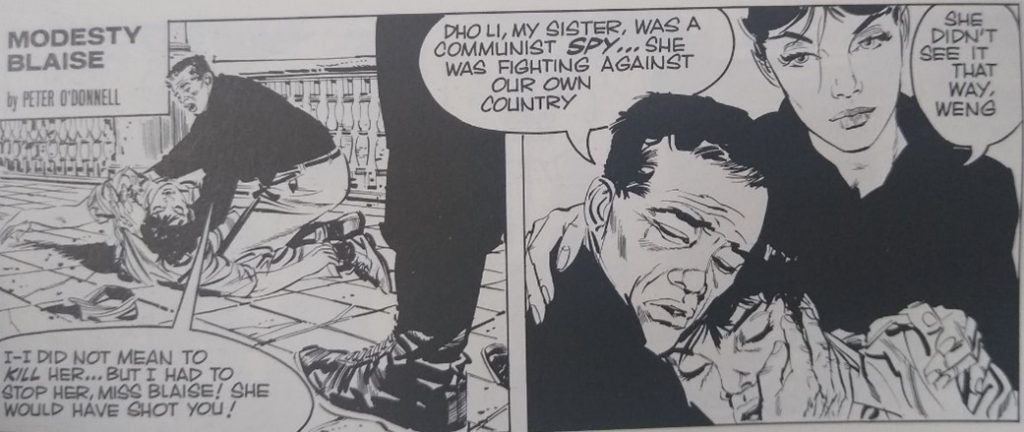

Seventh Moon , by John Rankine

A debut author, I think. When spaceship Interstellar Two-Nine goes missing on its approach to the ‘polite’ planet of Bromius, Dag Fletcher of the Inter-Galactic Organisation goes to investigate. With such a set-up, I suspect that this will become an ongoing series of some sort. It’s typical Space Opera and paradoxically remarkably mundane, even down to the repeated descriptions of how gorgeous all the women are, with the exception of the lead female character, who is deliberately annoying. 3 out of 5.

Pavane: Brother John, by Keith Roberts

In this third story from Roberts’ alternate History, where Elizabeth I was assassinated in 1588, we are given the chance to see the effect of religion upon this alternate life. As this is a world dominated by the Roman Catholic faith, it is an interesting perspective on what we have read so far.

Brother John is an Adhelmian monk who is given the task of recording, for the benefit of Rome, all stages in the proceedings of The Court of Father Hieronymous, Witchfinder in General to Pope John. He begins to dare to question the practices of the Church during a version of the Inquisition, and is so affected by what he sees that he begins to lead a revolt against the Church. The ending is rather enigmatic, in that in a crowd of acolytes Brother John experiences a vision showing an alternate future, a more positive one than that experienced by the masses. Leaving on a boat to Rome, the boat capsizes with no one to be found. This development of this series continues to impress.

Well, it’s taken a bit longer than it has in our world, but it seems that some sort of religious reformation is beginning. It’ll be interesting to see where this social upheaval leads, and I’ll read the next story to see if this idea evolves further. 4 out of 5.

The Pace That Kills by Alistair Bevan

From an alternative past to an alternate future, though from the same writer, because Alistair is actually Keith Roberts, who we have just read!

The two stories however couldn’t be more different. The Pace That Kills is evidently inspired by the newly introduced 70-miles-per-hour speed limit on Britain’s motorways. It is a world where this obsession with speed is taken to its limit. The government have politicized speed limits and uses black boxes in the vehicles to control speed in most people’s vehicles, but rebellious types adapt their vehicles, deliberately race each other and flagrantly ignore the limits.

Johnny Morris and his friend Tinker are witness to a seemingly fatal accident. They rescue a girl and meet the officious Masterwarden of Sector Twelve in West London, Horace J. Bigge. Afterwards, we discover that they work for Peter Hanssen, the leader of the Driver Party, for there is an ongoing political war between the Motorists, known as Drivers, and the Pedestrians, called Peds.

The survivor of the accident, Moira Alice Kelly, is taken to hospital, interrogated by Bigge and sentenced to torture and death. Despite Nanssen’s wishes, Morris and Tinker decide to attempt a rescue. It doesn’t go well, but Moira is released. Bigge is also captured and there follows a bizarre interrogation after which Bigge is set free, but dies by being run down on the road. Moira enthusiastically explains how she became a motor addict to Nanssen. They begin a relationship, only to find that Kelly is an undercover Warden. The story finished unconvincingly.

This is a really mixed-up story. Part adventure, part satire, in the end it is not a good example of either. It is generally uneven in pace and plot, veering between unsubtle satire and making a serious point. There’s a huge clumsy dollop of ‘telling’ the reader things in the middle as well.

Generally, things are usually ramped up to excess throughout this overlong story, which diminishes it overall. Difficult to believe that these two stories are from the same writer, which may be the point of the pseudonym. 2 out of 5.

The Run by Chris Priest

Something to freshen the palate a little now. This is a debut story in Impulse from someone who has made quite a name for himself through his critical comments in recent months – it was Chris that Kyril wrote an open letter response to in his editorial of Science Fantasy back in January. He is also currently a regular critic in the British Science Fiction Association’s in-house magazine, Vector.

With this in mind, it is interesting to read some of Chris’s fiction rather than his critical work. It is OK but nothing special. Senator Robbins, driving in his car, is summoned back to his base in an emergency. As he gets closer to the headquarters the journey becomes increasingly fraught as the road is surrounded by angry jeering teenagers known as Juvies.

Clearly tapping into the feeling of unease that many older people have about teenagers of today, the gist of the story is that the Juvies are going to take over the world, incite rioting and basically destroy law and order, and that this is the start of the revolution. There’s some nice touches, but the ending is annoyingly enigmatic. This is clearly a beginner’s work, but I’d be interested to see more of this from Chris. 3 out of 5.

Cry Martian, by Peter L Cave

A story of little Timmy who tells his mother that he has found a Martian camp whilst playing out in the woods. The twist in this brief story is that he is on Mars. Short but fairly effective, if forgettable.

3 out of 5.

Homecalling (Part 2 of 2) by Judith Merril

Back to the second and final part of Judith Merril’s story. Last time we found nine-year old Dee and her younger brother Petey stranded on a planet and taken in by the insect-like Lady Daydanda.

In this second part we read of further attempts to communicate and understand each other. Dee learns to translate the thoughts Daydanda is telepathically putting in her head. In return, Daydanda learns more about the humans. When Dee and Petey return to their rocket, Dee allows one of Daydanda’s sons to enter the burned-out spaceship with them, and through the son Daydanda can communicate further. She discovers what ‘machines’ are, that the place they are in is ‘a spaceship’ and that it can travel to places beyond their world.

Daydanda’s concern for the children and willingness to care for them is made more difficult by Dee’s seemingly illogical desire to be with her Mother. The aliens eventually are allowed access to the cockpit where both of her parents are dead, and much of the last part of the story shows us Daydanda’s logical, if erroneous, reasoning for why Dee does not want to see her Mother dead in the Spaceship. Intriguingly, the ending feels rather creepy, although I suspect the idea is meant to be a happy one, where Petey and Dee are willingly left in the presence of the Mother – for now.

As I said last month, even though there are issues of this being a reprint, it is a great story. Merril’s description of the aliens, and the thought processes they go through to make their decisions and choices is wonderful – but, of course, really it is the humans who are the aliens. 4 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

Mainly novellas again this month. The Merril finishes well, and may be the best thing in the magazine, although I am still annoyed about it being a reprint. I continued to enjoy the Pavane series, although I know that it is not for everyone and this latest installment will not change that view, I’m afraid. It’s intriguing to read Chris Priest’s fiction as opposed to his letter-writing. But then we have what even Kyril referred to last month as “typically Bonfiglioni space-fillers”.

I’m almost tempted to add the Rankine here as one, though that may be uncharitable. It’s OK, if just… boring. The Cave story Cry Martian tells us an old trope in a new way – but nothing new, there. However, The Pace that Kills is just awful. I suspect it has been there a while waiting to be used as “space-filler”.

So: a mixture of good and bad this month, leading to a lower-than-average, certainly of late, issue. With the dominance of new Associate Editor Keith Roberts this month, this may be a little worrying.

Onto this month’s New Worlds

The Second Issue At Hand

In contrast to Impulse, Mike Moorcock has opted for shorter stories with more variety this month. He’s also promised to tackle that perennial (and most touchy!) topic of religion.

In the Editorial, Moorcock warms up by tackling the topic of the supernatural. He refers to a new book about it, quoting its point that the supernatural may be connected to the natural, or normal, in a person’s mind, and that Ballard and Philip K. Dick write about this in different ways. The final paragraphs suggest we should see more sf incorporating drugs to explore this new territory.

My issue with this is that you may need to take drugs to understand such stories. As I don’t partake – beyond the odd cup of tea! – such stories tend to leave me cold.

And talking of stories, to the stories!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

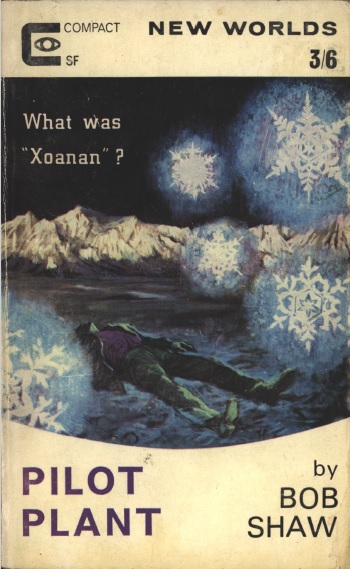

Pilot Plant by Bob Shaw

Here’s the welcome return of Bob Shaw, last seen in these pages back in October 1965 with …And Isles Where Good Men Lie.

Whilst involved in an aeroplane test flight accident, aerospace engineer Tony Garnett hears a voice say, “Get me out of here Xoanon.” When he is recovering in hospital, he tries to work out who Xoanon is and where the voice came from. He contacts his deputy Ian Dermott to cancel the firm’s current project, a flying wing for civil aviation. Four months later, Garnett is back to work but finds that, despite his wishes, work has been continued in secret. His attempt to meet a worker involved in the project is unsuccessful – the man faints – but Garnett finds that the poor unconscious worker has recently been sent away on a special training course.

He takes his nurse Janice Vickers away on a weekend but really goes to find the place in Harlech, Wales, where this training course has been held. As Garnett gets near he realises he has been there before but has strangely forgotten about it. The date with Janice doesn’t go well, and Garnett ends up in Janice’s chalet whilst she ends up in his. This is a fatal mistake, as during the night there is an explosion in Garnett’s chalet where he would have been sleeping and Janice dies. The last words she mumbles to Tony are also about Xoanon.

Things now get stranger. Garnett is told by the police that the explosion was caused by a meteorite strike. After being interrogated by the police Garnett returns to the factory where he is told that a wing is being built for a customer by the name of Xoanon, who is one of a group of extraterrestrials. They wish to use the wing to collect something lost off the coast of Wales.

Dermott tells Tony that he has been manipulated by Xoanon from the start, but the accident meant that a metal plate was put in his skull which broke the contact between him and Xoanon. Garnett is shot by Dermott. Surviving this, Tony captures a test plane about to take off and attempts to rendezvous with Xoanon’s spaceship hidden in the upper atmosphere.

Tony meets Xoanon, who in Bond-villain fashion explains all to Garnett. Garnett also meets Janice again, because – surprise, surprise! – she wasn’t killed, but is now in the body of an alien. Tony decides not to return to Earth.

It’s good to see Bob back, but this is relatively mediocre stuff. The setting’s good, the prose too, but the plot got wilder and wilder until it lost credibility for me. The ending is particularly weak, as there are elements seemingly key to the plot that are not explained – do the aliens retrieve their device? – and the abrupt end of the story means that we do not find what happens next.

I think Bob’s trying to write a contemporary thriller with a science-fictional element, but it didn’t quite work. 3 out of 5.

The Ultimate Artist, by Richard A. Gordon

We’ve met Gordon before with his story A Question of Culture back in Science Fantasy in December 1965. We’re treading similar ideas here, as this story is about what happens when an Artist named Zacharias decides to retire. The story is told by a narrator who has spent much of their life following Zacharias as he travels across the galaxy. When Zacharias performs for the last time, there are consequences for the narrator.

There’s some nice descriptions of what it is like to be enraptured by a performance. It is about the joy of the experience and fan-worship. Rather like seeing The Beatles or The Rolling Stones as they retire, I guess. 3 out of 5.

Rumpelstiltskin, by Daphne Castell

Daphne has been popping up with some regularity in New Worlds of late. This time she retells the old fairytale of a princess locked away in a tower from the perspective of Rumpelstiltskin. Well written but not really memorable. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Unification Day, by George Collyn

George Collyn was last seen in last month’s issue waxing lyrical over the work of Kurt Vonnegut. Here we’re seeing his fiction. I quite liked the set-up of this one, in an alternate history where Britain has been unified with France. This is emphasised by the point that although the story is set in Scotland, there’s lots of wine, pastries and Camembert around!

The narrator tells us of what happens when he and his wife go to stay with his posher brother-in-law for the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of Unification Day. As the narrator is an advovate of English Home Rule and the brother-in-law is a Francophile, as you might expect it doesn’t go well. Much of the story here shows us how the British are treated as underdogs and lesser citizens, how the language is down-graded in society and British culture is derided. The consequence of this is the story-teller is determined to continue his fight in the future. An interesting version of the traditional Scottish – English independence debate, which makes valid points, but then doesn’t seem to go anywhere. 3 out of 5.

Secret Weapon by E. C. Tubb

The return of an old-school regular. Students from different planets begin at an Earth academy. Armitage is an unpleasant student who finds it difficult to fit in, and reacts violently to what he sees. He graduates – eventually. However, the reason for his behaviour is revealed at the end of the story.

This is a story with an almost Heinlein-like tone, which may wrongfoot the reader. It doesn’t show humans in a good light, though. Nicely written, even if it is a one-trick kind of tale. 3 out of 5.

Fountaineer, by David Newton

This month’s lyrical story, about a fountain in a village in Italy and its creator. Lots of lush prose which otherwise has little point. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

Fifth Person Singular, by Peter Tate

A story of awareness from different perspectives. An alien shows us his perception of his world. When he meets Ahn, he then discovers that there is more than one way of looking at things. Appropriately inner space, this one. A romance that takes navel-gazing to another dimension. 3 out of 5.

A Man Like Prometheus, by Bob Parkinson

A more typical romance story now. A space pioneer returns from “Out There” to meet Rosamund, his Earthbound love, after their careers and a genetic disorder have kept them apart. I like what the writer is trying to do here – romance in a SCIENCE FICTION magazine?! The problem is that it’s not that well done and comes across as somewhat mawkish and maudlin. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

Girl, by Michael Butterworth

A person visits an old barn filled with ancient and decaying artifacts. Lots of descriptions of things in a dream-like state. The twist in the tale is that this story is after some sort of an apocalypse which they have caused. Lots of lyrical allegory which tries to mean more than it does. 3 out of 5.

Clean Slate, by Ralph Nicholas

Stranded, John Sumpter attempts to fix a broken-down spaceship without help or spare parts. It seems impossible. Expecting the end, Sumpter and his friend Orlando swap tales about their pasts. They experience some kind of cosmic event, which allows them to fix their ship and go home. Unconvincing. 3 out of 5.

A Different Kick – Or How to Get High Without Going into Orbit, by John Brunner

After last month’s strange serial, here’s John Brunner in non-fiction mode. This is an abridged transcript of an address given by Brunner at the London Worldcon last year. It was mentioned by both editors after the event as a landmark speech and caused a bit of a stir at the Worldcon, I gather. I assume for that reason it is given here.

Reading it, I can see why. Brunner examines what sf readers like and don’t like about non-sf novels, and how non-sf writers have managed to be successful in the genre. It’s well thought out and makes valid points using lots of references to different author’s work. At the end Brunner echoes Moorcock’s ideas that sf needs to move away from its pulp origins and be something new and different if it is to inspire and succeed in the future. A “Look forward, not back” kinda thing. It is well done, but is nothing new to regular readers.

Letters and Book Reviews

Assistant Editor Langdon Jones tackles one book in depth this month – Dreams and Dreaming by Norman MacKenzie. The reason given for this is that it gives the reader an insight into Fantasy writing by explaining the workings of the inner mind. Really though it seems to be a justification for all those stories we are currently reading about visions and dream-states – there’s some in this month’s issue, for example.

James Colvin (aka Mike Moorcock, don’t forget!) covers a number of story collections in some detail. The Best from Fantasy & SF Volumes 11 and 13 come out of this dissection pretty well, although Colvin feels that Volume 11 is better than Volume 13. By contrast, Lloyd Biggle’s All the Colours of Darkness is “a weary book”. Walter M Miller’s Conditionally Human collects three “above average” novellas from the fifties. Daniel F Galouye’s latest, The Lost Perception, is “unsuccessful”.

After being absent for a while, the Letters pages this month are very entertaining, as Moorcock answers criticism of his "attack" on religion in his Editorial of Issue 158 (January 1966). Too long to quote, but the responses on both sides are fulsome and interesting.

Summing up New Worlds

Once again Moorcock has gone for breadth rather than depth here this month. This means that there’s more to like and the range of material is good, but overall the issue feels a little underwhelming. The much-vaunted Bob Shaw story disappointed, for example. There’s nothing here that is not entertaining, but at the same time there’s not a lot here worth remembering.

Summing up overall

Once again, we have the two magazines showing different aspects of the genre. Whereas Impulse has gone for less stories and more depth, New Worlds impresses with its range.

This makes the choice difficult in that we are rather comparing oranges with apples. It also doesn’t help that neither magazine truly impresses this month. They are not bad, it is just that we’ve had better from both editors. Each issue has its own disappointment.

In the end I’ve opted for Impulse as the better, although I could easily see other readers opt for New Worlds, for the reasons I have given above.

With all this talk of religion, I see the title of John Baxter's novel in next month's New Worlds with a certain degree of irony…

Should be interesting! Until the next…

![[May 10, 1966] Rocky Jaunts (June 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1966] A Respite (June 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510amz-0666-cover-575x372.png)

![[May 6, 1966] Blaise-ing Wreckage (<i>Modesty Blaise</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/MB16.jpg)

![[May 2, 1966] By Any Other Name (June 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IF-1966-06-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1966] Ormazd and Ahriman (May 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 26, 1966] Inner Space, Romance and Religion <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, May 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Impulse-NW-May-1966-619x372.jpg)

![[April 24, 1966] Playtime’s Over (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Celestial Toymaker)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660424thetoymaker-672x372.jpg)

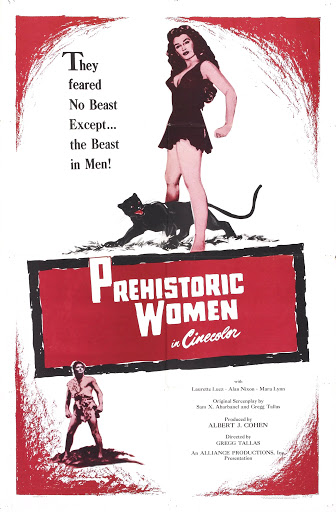

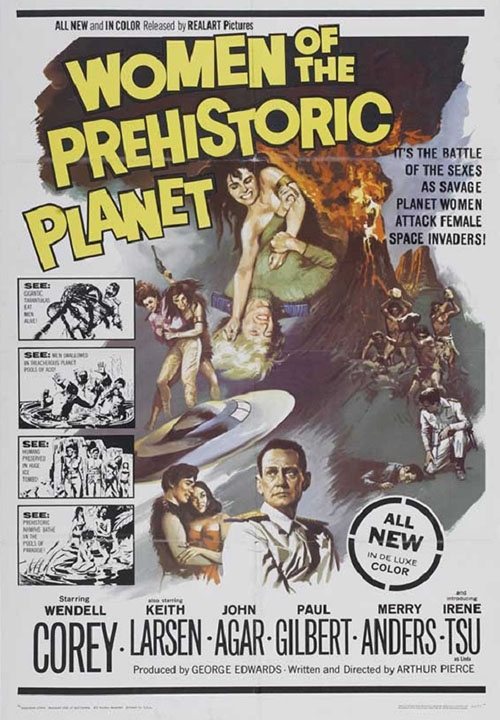

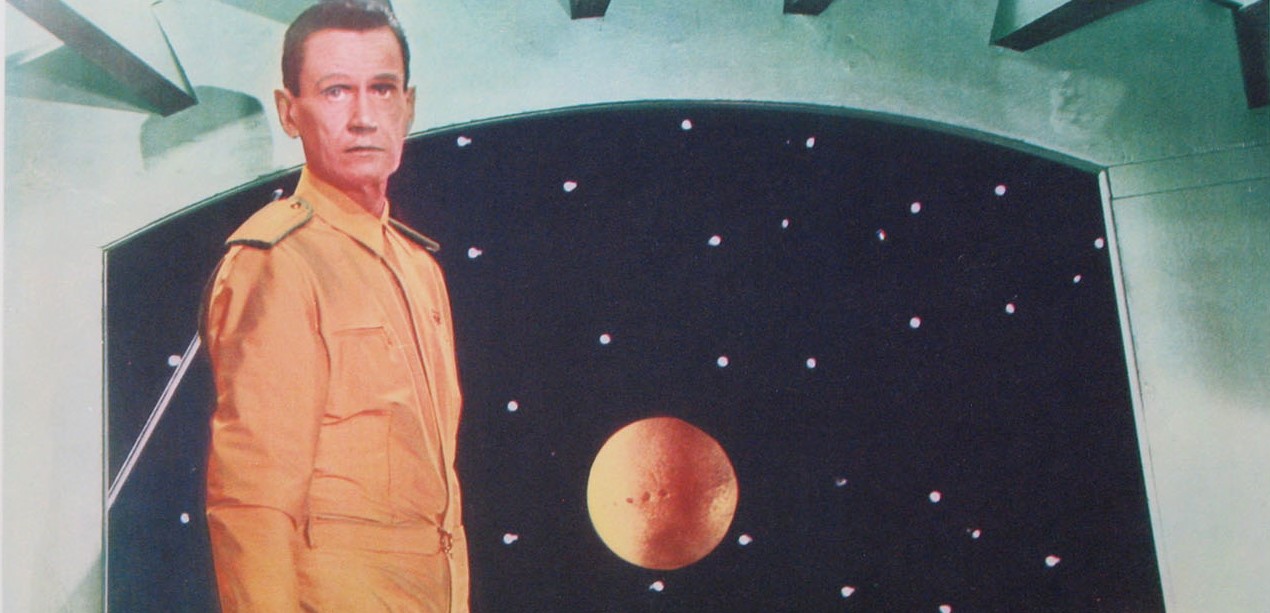

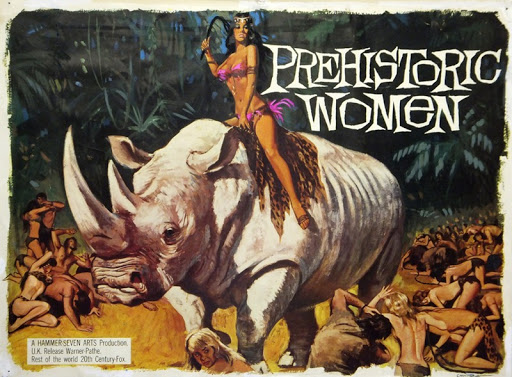

![[April 22, 1966] No Man's Land (<i>Women of the Prehistoric Planet</i> and Further Female Filled Fantasy Films)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/women_of_prehistoric_planet_1966-3.jpg)

![[April 18, 1966] Rocannon and the Kar-Chee](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/660418books-512x372.jpg)