by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

As we’re in that strange time between post-Christmas and pre-New Year I’m pleased to type that my copies of both New Worlds and SF Impulse have manged to arrive amidst all of the Christmas mail.

Thank you, postie!

And I am pleased that I actually got two magazines. The rumours of the magazines' decline are still about, although I have no further news. I am still hopeful that 1967 will see them continue. More news when I get it.

With that over, let’s start with New Worlds.

A Guest Editorial this month, from Mr. Brian W. Aldiss, no less. Clearly Mike’s taken time off, and Brian has stepped up – which means that the two issues this month have the Editorial-ship of Aldiss and Harrison. (Where have I seen those two names together before?)

Here Aldiss extols the virtues of the sf pioneer H. G. Wells. Shouldn’t be too surprising, though, as amongst his other many talents Brian is the Vice-President of the H. G. Wells Society, founded nearly 7 years ago. Moorcock last month said that they had hoped to run a piece on Wells’ centenary. I am assuming that this was the (delayed) piece.

It’s an expectedly congratulatory piece – Mr. Aldiss has come here to praise him, not bury him! – but as ever Brian’s writing is always lively and entertaining. There’s a good case made here to celebrate Wells.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

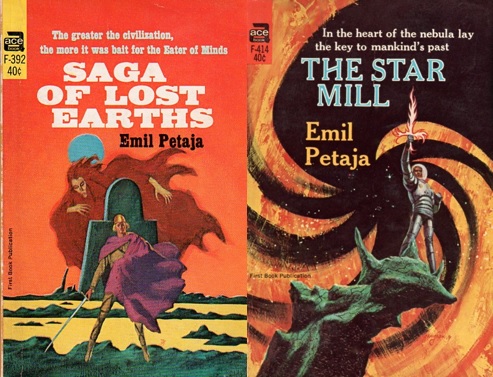

The Day of Forever, by J.G. Ballard

Another melancholic tale from Mr. Ballard. This one has Dying Earth vibes, described as “a world of Nordic gloom” as it posits a future where the Earth has stopped rotating. As a result, in the town of Columbine Sept-Heures, it is a never-ending twilight. This creates for the few survivors a dream-like setting and consequently there’s a lot of stuff here about dreams, or rather not-dreaming, in a surreal setting, as well as Ballard’s usual musings on entropy and time. Here Halliday meets odd characters and dreams of a woman he has seen. More of a mood piece than anything else, I feel. Not a lot happens but the prose is appropriately dream-like in this surreal situation. 4 out of 5.

Saint 505 , by John Clark

A new author to me, with an oddly-styled story of a glowing computer and its creation and management by a mad scientist. Almost poetry but not quite. 3 out of 5.

Sun Push, by Graham M. Hall

Trench warfare that wouldn’t be out of place in the First or Second World Wars – except that this one’s in Britain. Unremittingly grim, Private Time St. John Smith with his Battalion companions Eamus and Sergeant Trelawney fight their way across Southern England. Nasty things happen – “War’s a filthy business”, one of the characters says and that seems to be the main point of this story. To prove it there are a number of atrocities that occur here – for example, captured prisoners are put into brothels, sedated and forced to 'perform', amongst other indignities, something our shell-shocked characters accept and take advantage of. War is hell, etc etc. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Onto better stuff. Roberts continues to sell his fiction to the companion magazine of the one he is currently editing. As if this wasn’t enough interaction between the two magazines, the banner tells us that this story was inspired by New Worlds editor Mike Moorcock’s serial novel, The Ice Schooner, currently being serialised over at SF Impulse. So this is another ice-rimmed Fantasy, part Konrad Arflame, part Conan – or is it Elric? The aloof Coranda demands a dowry for her hand in marriage – a unicorn’s head. Rich suitors experience many hardships and not all survive, to win Coranda’s prize, at a cost.

Roberts' tale is grim and yet floridly written, and quite enjoyable, but borrowing Moorcock’s setting and being rather Edgar Rice Burroughs or Conan in style means that it is somewhat derivative. Nevertheless, an interesting alternative take on Moorcock’s idea that I actually enjoyed more than Moorcock’s this month. 4 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

I had to read that title more than once in order to type it! A story about life from the perspective of a cockroach that wakes up human. No explanation is given for this, but I quite liked it. It shows us that life can be just as weird if you are an insect instead of a human.

Memorable – not just for the title! 4 out of 5.

The Silver Needle, by George Macbeth

Another drug culture related tale but this time in the form of a poem, filled with sex and drug references, and perhaps designed to shock, provoke and amuse. Not as exciting as that summary suggests. 3 out of 5.

Echo Round His Bones (Part 2 of 2), by Thomas M Disch

Captain Hansard continues his life between matter transmitters. Having been rescued at the end of the last part by Bridgetta, the wife of Panofsky, the inventor of the transmitter, we begin this part surrounded by multiple Panlofsky’s and Bridgettas. It seems that every time someone passes through the “manmitter” (ugh) a copy, or echo, is made.

Hansard finds himself unable to go back to his previous world, but is instead offered marriage by Panofsky to one of the copies of his wife. This is not a Heinlein story, right? Or Doctor Strangelove? There are times when it seems very much so. There’s a lot of talk by Panofsky of religion, suicide and souls at this point. And, of course, all of the copies of Bridgetta are wonderful at what they do.

There’s also the pressing issue that the world is about to destroy itself in days… or rather worlds, for it is from Mars that the missiles are about to be launched. Remember – that was Hansard’s original mission, to take a message to Mars.

Confused yet? This is a story that seems to throw everything in at this stage, and as a result it didn’t quite work for me. Clever, yes. And complicated. But I did feel it was trying to spin too many plates at once at the end. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews

This month Judith Merril takes a step away from her reviewing in the Magazine of Fantasy & SF to review for us Brits. Here she mentions in some detail C. Maxwell Cade’s Other Worlds Than Ours, although as she puts it, “with a touch of my own professional bigotry” to be more impressed than she thought she would be.

James Cawthorn, more briefly, reviews Thomas Burnett Swann’s Day of the Minotaur, Cordwainer Smith’s Quest of the Three Worlds, Roger Zelazny’s The Dream Master, Poul Anderson’s The Corridors of Time and a non-fiction book on archaeology, Approach to Archaeology by Professor Stuart Piggott.

No Letters pages again this month. They all seem to be writing for SF Impulse instead (see below.)

Ballard of a Whaler , by J. Cawthorn

We’ve met James as an artist already this month as a reviewer, but here he is widening his repertoire for the magazine by writing a short tale which also makes use of Moorcock’s Ice Schooner setting. Its purpose isn’t really clear, other than to try and be funny. Who said SF readers don't have a sense of humour? Sigh. 2 out of 5.

Summing up New Worlds

In some ways we seem to have been put into a routine at New Worlds. It is little different from the last issue – more Disch, more Ballard, more Keith Roberts, the appearance of Aldiss…nothing wrong with that and the stories are generally good. Kit Reed’s is perhaps my favourite in this month’s issue. With all this homage to The Ice Schooner, it's almost as if echoes have been created from the original story! But it does feel a little like this issue could be the November issue just as easily. And so, as last month, a very good issue but not an outstanding one.

The Second Issue At Hand

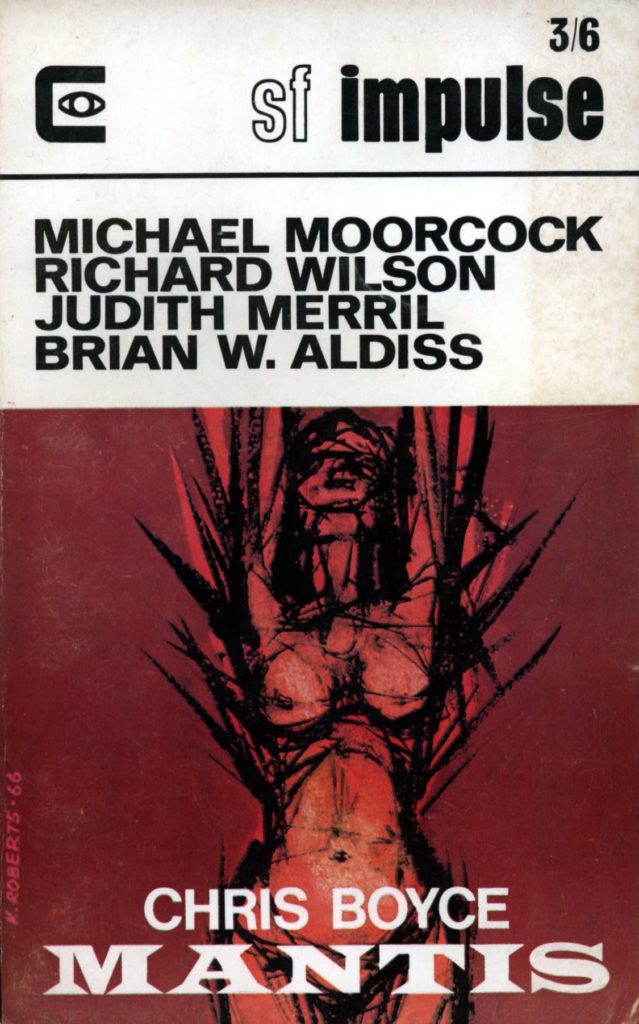

And now to SF Impulse. Oooh look: nakedness from Keith Roberts. Are we trying to be controversial? (See Letters pages, later.)

The Editorial is a return to that subject we’ve discussed many times before: What is Science Fiction? – before reviewing Gordon Dickson’s Mission to Universe. Harrison likes it.

Illustration by Keith Roberts

The return of Chris after his fair-but-not-terrific The Rig in the September issue. One again, fair-but-not-terrific, and certainly not as good as the magazine would have me believe. Far too much magazine space (32 pages!) is taken up with the story of sculptor Eric Summerscale, who finds himself being investigated by Condominium Security because his wife Ursula is suspected of being a spy for the Conclavists. Despite its attempt at breeziness, almost becoming a Robert Heinlein story, Mantis feels long, too long, to the point of dullness. Not a promising start; this one tries so hard and yet feels like filler. 3 out of 5.

Green Eyes by Richard Wilson

And then it gets worse, as the laboured Battle of the Sexes idea is continued by Richard. His first story in this series was Deserter in the first issue of Impulse in March and I felt that it was the weakest element of an otherwise strong issue. This is just as awful. The key character in this war is Phoebe, a man in women’s clothing. If it is meant to be funny, it is not. Otherwise, it is another laboured space filler, covering similar ground to Mantis. 2 out of 5.

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor this month continue the discussion of Sex in SF that E. C. Tubb started a couple of issues ago. Chris Hebron, who seems to be all over this issue, responds, as does New Worlds’ Assistant Editor Langdon Jones. The Editor (presumably Harrison, but could be just as easily Keith Roberts) points out at the end how pleased he is for the magazine to have its first real controversy. To me it feels like an attempt to generate mock outrage. Never have these magazines seemed more interchangeable.

Brian Aldiss reviews Thomas M Disch’s The Genocides

A long and thorough review of Disch’s novel. According to Aldiss, the book’s not perfect but there’s enough positives to make me want to read it.

Illustration by Keith Roberts – look, more boobs!

The Shrine of Temptation by Judith Merril

An anthropological story, telling of the strange culture seen by a scientific study through the native Lallayall (aka Lucky). It draws you in, this one. Reminds me a little of Chad Oliver’s writing, but with the usual high standard of Judith. Revelations abound! The first decent story of the issue. 4 out of 5.

Coincidence by Chris Hebron

Another returning author, and not just from his appearance in the Letters Pages this month. Chris was last seen in SF Impulse in October. It’s an epistolary tale, told through communication between two academic researchers. Like the Merril story, there are anthropological elements, although here we also have weird happenings that seem more like witchcraft, with strange images, sex fantasies and things only the narrator can see and hear. Fritz Leiber would like this one, I think. There’s mention of breasts in a vain attempt to grab my attention – this seems to be a theme this month! – and even shock me in a story that had trouble maintaining my interest. Can’t see the American magazines wanting this one, though. 3 out of 5.

Grutch by Pete Hammerton

Another story that is meant to be amusing (the banner says that it is “a delightfully funny episode from a new and zany talent”), but did not stir me. Some sort of sub-Dickensian style story in a science-fictional, future setting. Luke Varm claims to talk telepathically to mice from Mars who need his help to return home. As silly as it sounds, and once again, this one feels oversold. I am always wary of stories where I am told “this is funny”, because they rarely are. 2 out of 5.

Scary Illustration by Keith Roberts

The Ice Schooner (Part 3 of 3) by Michael Moorcock

Our journey across a frozen world with Konrad Arflame concludes this month. When we left it last month, Konrad and his group of Ulrica Ulsenn (who Konrad has secretly slept with), her arrogant husband Janek, Ulrica’s cousin Manfred and the harpoonist Long Lance Urquart were on the Ice Maiden, heading North to find the legendary New York and possibly the mystical Ice Mother. They were approaching an icebreak.

The boat survives, although there is increased tension as the boat nears volcanoes. Konrad is told by Ulrica that First Officer Petchnyoff and Janek Ulsenn plan to kill him. Before this can happen, though, the boat is attacked by barbarians. Petchnyoff is killed and Konrad is wounded. The weather turns foggier and colder, and the morale on the boat worsens but this changes when eventually the boat approaches New York.

However, the boat is damaged when it hits a wreck and there is another raid on the ship by the barbarians. In an attempt to escape the raiders, the boat is destroyed. The survivors are captured by barbarians riding polar bears and are taken to New York. They are told that the ice is melting. Urquart persuades the barbarians that Arflame should be taken to the Ice Mother’s court. For this, Urquart has made a deal to make a blood sacrifice to the Ice Mother. Manfred is castrated and eventually dies. Urquart is killed in combat by Arflane.

In New York they meet Peter Ballantine, who explains to them the origins of the city and how the people there have invented machinery to keep the ice at bay. Ulrica decides to stay, thinking that this is the future, whilst Konrad leaves alone to find the Ice Mother.

I still enjoyed the setting, though this part feels uneven and even a bit of a downer. Its melancholic nature signals that things must change and yet some cling to the traditions. Will Konrad find the Ice Mother? It looks like we’ll never know. 3 out of 5.

Summing up SF Impulse

A very middling kind of issue this month that seems to be filling space without any real impact, dominated by the dull and predictable Chris Boyce story. The Moorcock was fine but seemed to fizzle out a little, and the Merril was good, but overall this issue feels like it is trying too hard, filled with material that was at the bottom of the pile, or at least full of New Worlds cast-offs.

Summing up overall

After a run of SF Impulses that have been better, from my comments above it may be unsurprising, yet pleasing, for me to say that there’s no contest this month – New Worlds is by far the better issue, even when both magazines seem to be in some sort of slight slump.

Worrying signs aside, we do at least have something to look forward to: this is at the end of the New Worlds issue:

Until the next (forward, 1967!)…

![[December 28, 1966] Ice Worlds, Telepathic Martian Mice and Echoes (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, January 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/New-Worlds-Impulse-Jan-67-1-672x372.jpg)

![[December 26, 1966] Harvesting the Starfields (1966's Galactic Stars!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661226plough-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1966] Unquiet on the Romulan Front (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Balance of Terror")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661224title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 22, 1966] Who's In Charge Here? (<i>The Monitors</i> by Keith Laumer and <I>The Nevermore Affair</i> by Kate Wilhelm)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661222covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1966] Above and beyond (January 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i> and a space roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661220cover-656x372.jpg)

![[December 18, 1966] The Manchurian Colonel: <i>Space Patrol Orion</i>, Episode 7: "Invasion"](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Raumpatrouille-Orion_1499343747406665-672x372.jpg)

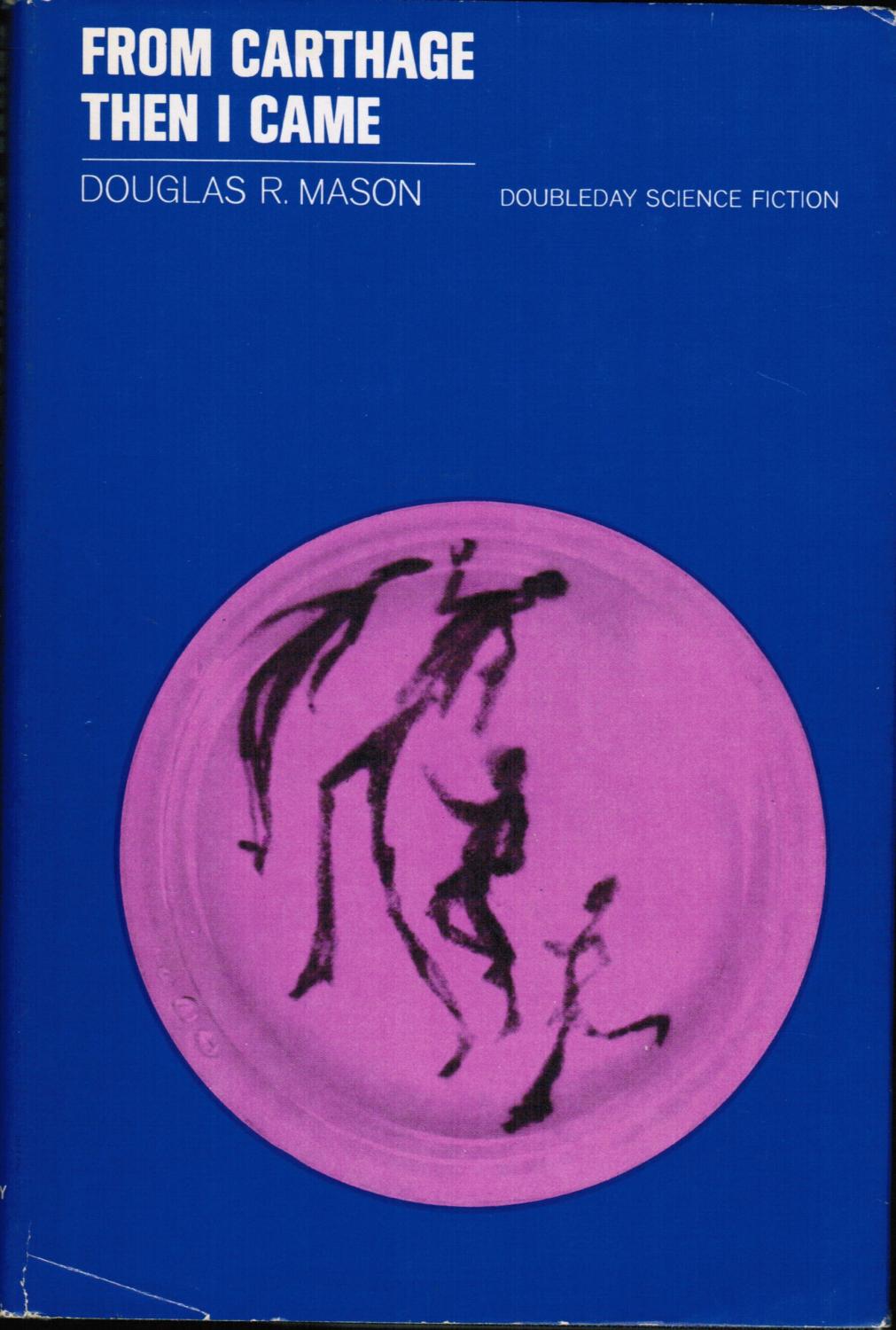

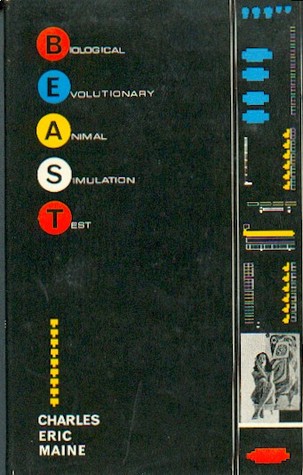

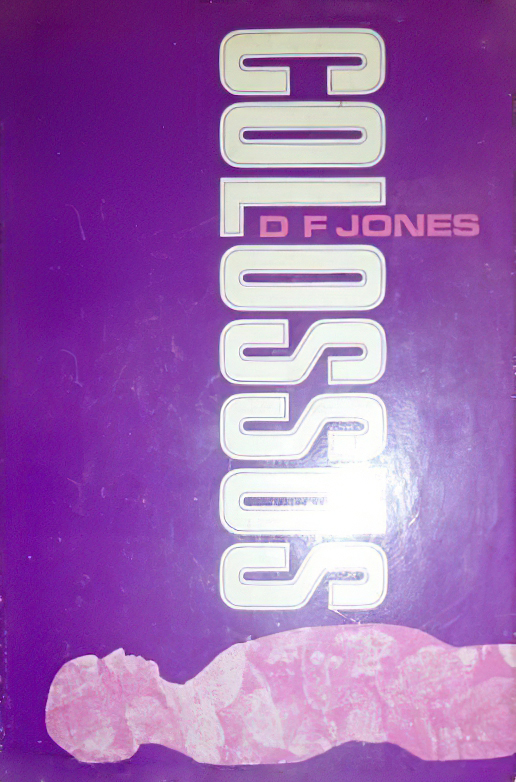

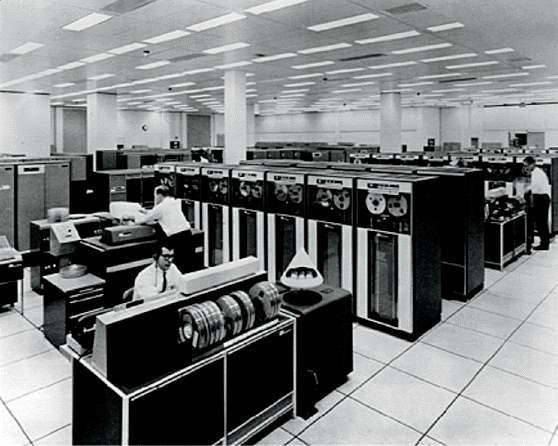

![[December 16, 1966] The God Slayers (two computer-themed novels)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661216covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 14, 1966] (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Conscience of the King)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661214title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 12, 1966] An Explosive Ending (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Power Of The Daleks [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661212assemblyline-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1966] Hot and Cold (December Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661210covers-672x372.jpg)