by Victoria Silverwolf

Keep Watching the Skies!

The good citizens of Michigan were recently reminded of the warning I've quoted above, from 1951's The Thing from Another World (a loose cinematic adaptation of John W. Campbell's 1938 novella Who Goes There?).

Father and son describe what they saw.

Folks in Washtenaw County (just look for the city of Ann Arbor on the map, and you're smack dab in the middle of it) reported seeing strange lights in the sky last month. Supposedly, a UFO even landed in a swampy area near the tiny community of Dexter Township.

Looks like a classic flying saucer to me.

About one hundred people witnessed these phenomena. Naturally, the federal government got involved. They sent astronomer J. Allen Hynek to the area to check things out. Reportedly, he thinks at least some of the sightings can be explained as swamp gas. One politician isn't so sure.

Note that the article uses the phrase marsh gas. One person's swamp is another person's marsh, I suppose.

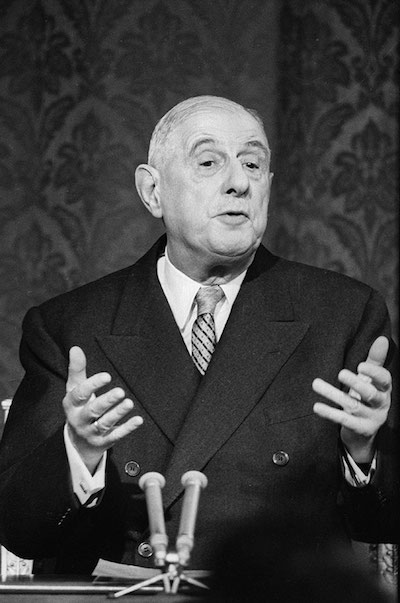

Gerald R. Ford is a United States Congressman from the Grand Rapids district of Michigan, so this situation strikes close to home for him. (He's a Republican, and the Minority Leader of the House of Representatives. Maybe this event will make him famous.)

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

Here's a picture of Representative Ford and wife Betty on a recent fishing trip, so you'll recognize him if his face shows up in the news in times to come.

It Makes a Fellow Proud to Be a Soldier

While some Americans are tracking down UFO's, others are searching for ways to justify their nation's involvement in the conflict in Vietnam. As a counterpoint to the many demonstrations against the war, a patriotic song celebrating the heroism of the Army Special Forces has been at the top of the charts for several weeks. The Ballad of the Green Berets, sung by Sergeant Barry Sadler, seems to have struck just the right note with many conservative music lovers.

Personally, I prefer the Tom Lehrer song I have alluded to above.

Hunting Through the Pages

Meanwhile, I've been searching for good reading. Take, for example, the latest issue of Fantastic. Fittingly, many of the stories feature characters who are on quests of one kind or another.

Art by Frank R. Paul.

(I might add that I had to search through piles of old pulp magazines to find the original source of the magazine's cover art. It turned out to be the back cover of the September 1944 issue of Amazing Stories.)

Confused? We'll get to an explanation of this weird scene later in the issue.

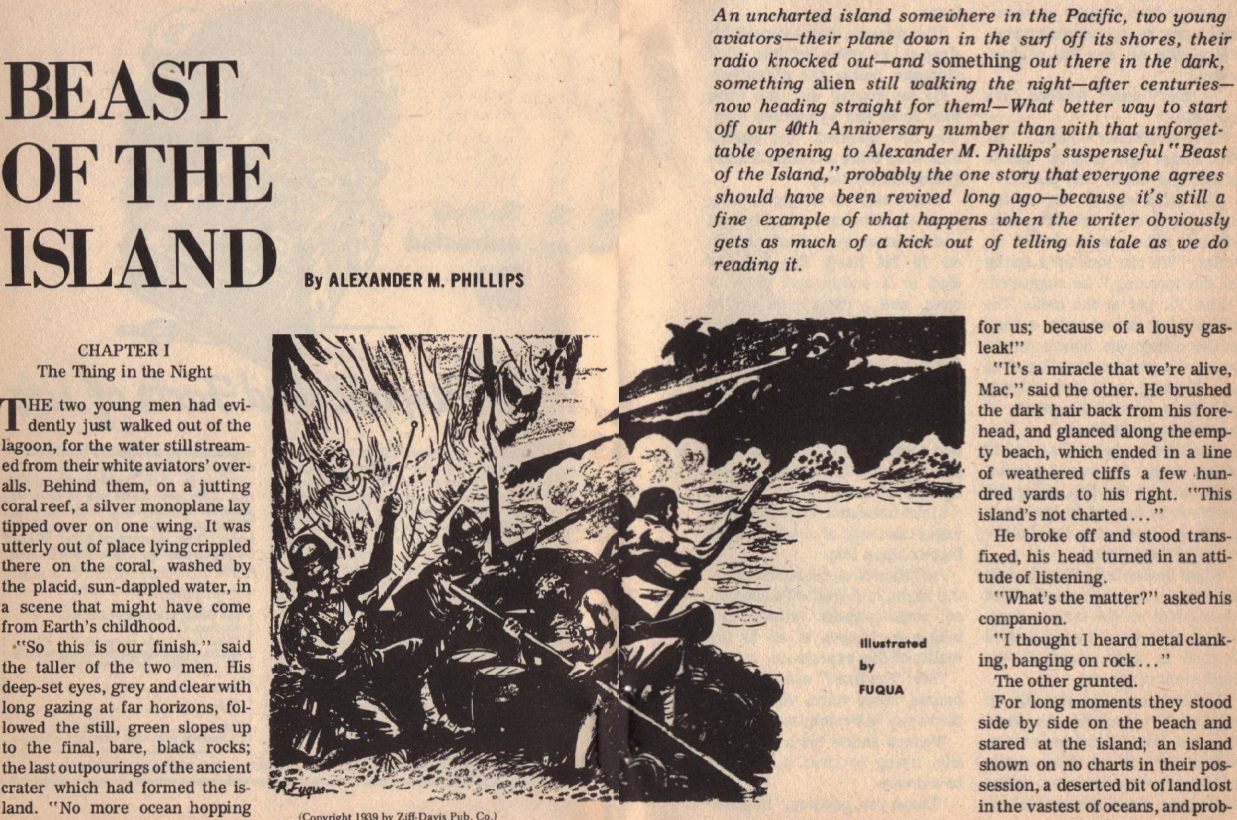

The Phoenix and the Mirror, by Avram Davidson

Let's begin our journey with a new novella from the former editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

The author's introductory note explains that the ancient Roman poet Virgil, author of the Aeneid, was depicted as a sorcerer in legends of the Middle Ages. (Davidson prefers the spelling Vergil, which I will use for the name of the fictional character in this story. He also prefers nigromancer to necromancer and Renascence to Renaissance, but that's typical erudite eccentricity on his part.) He also notes that this tale is the first part of a series to be called Vergil Magus.

Anyway, we begin in medias res, with Vergil trying to escape from an underground labyrinth full of malevolent manticores. (These are not the lion-scorpions of myth, but something more like large, clever weasels.) He manages to get out, winding up at the palace of an aristocrat with magical powers. She forces him to undertake the extremely difficult quest of creating a very special enchanted mirror, so she can see where in the world her daughter might be. He can't say no, because she steals one of his souls.

You read that right. People in this world have more than one soul, it seems. Losing one isn't fatal, but it seems to be so traumatic an event that Vergil feels compelled to undertake the nearly impossible task. He has to obtain unrefined tin and copper ore from the far ends of the known world, and then form the mirror through a long and laborious process. After many struggles, with the help of his alchemist sidekick, he manages to complete this onerous undertaking.

The mirror in use.

That isn't the end of his troubles, however. After instantly falling in love with the daughter after one glimpse in the mirror, he treks through desert wastelands, with an enigmatic Phoenician at his side, to rescue her from a Cyclops.

The lady and the cyclops.

This isn't the typical brutal, dimwitted Cyclops from mythology, but an intelligent, even sensitive creature. Multiple plot twists follow, and we find out why a phoenix is mentioned in the title.

Davidson keeps his baroque writing style under control here, and the plot is cleverly crafted. The background, which is kind of a mixture of the ancient world and the Middle Ages, with a strong dose of pure fantasy, is unique and interesting. Some readers may be impatient with several pages describing in great detail the exact method of creating the mirror, but I found it fascinating.

My one major complaint is that Vergil's lengthy and dangerous voyage to obtain copper ore is skipped over almost entirely, related in just a few sentences of flashback. I would like to learn more about his adventures there. Maybe Davidson plans to expand this novella into a novel, as authors of science fiction and fantasy often do. Otherwise, I greatly enjoyed this witty and imaginative excursion into a past that never existed.

Four stars.

Seven Came Back, by Clifford D. Simak

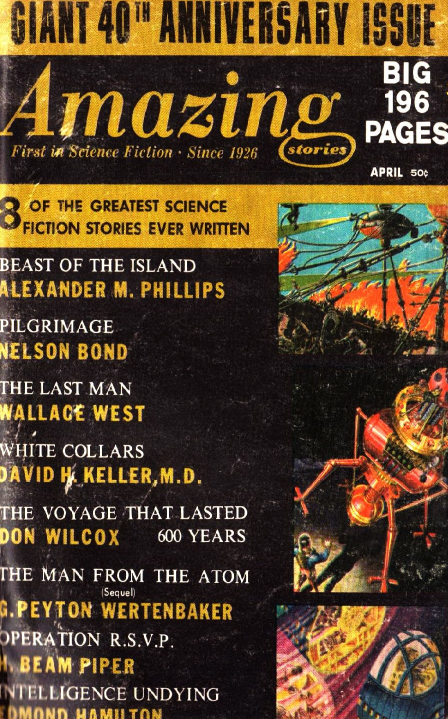

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

As usual, the rest of the magazine is filled up with reprints. Let's start with a tale from the pages of the October 1950 issue of Amazing Stories.

Illustrations by Arthur Hutah.

The setting is Mars, the favorite world of SF writers. Like many fictional versions of the red planet, this is a place where humans can survive without spacesuits. It's still a very dangerous environment, however, with all sorts of deadly creatures living in the endless desert.

The protagonist is on a quest to find the fabled lost city of the nearly extinct Martians. He hires a couple of tough guys to guide him through the wasteland. As we'll see, this turns out to be a big mistake.

Six Martians show up at their camp. It seems that they're the last of their kind, and they think that the men can lead them to a seventh. The Martians have seven sexes, you see, and this is their last chance to reproduce. (That must certainly make things complicated.)

If the humans help them out, they'll take them to the city, which is supposed to be full of fabulous treasures. The two roughnecks take off on their own, leaving the protagonist alone in the deadly desert.

Things get a lot stranger after this, and I don't want to give too much away. Suffice to say that the main character manages to survive, wins an unexpected ally, and has a mystical experience at the city.

The lost Martian city.

At first, I thought this was more or less a science fiction Western, with the hero heading for a showdown with the no-good polecats who left him to die. I have to admit that the plot went in completely unexpected directions. I'm still pondering the meaning of the ending. The author mixes space adventure with his usual warmth and concern for all living things and a touch of Bradbury's magical Mars.

Four stars.

The Third Guest, by B. Traven

The mysterious author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre offers a fable of life and death that appeared in the March-April 1953 issue of Fantastic.

Cover art by Richard Powers.

Like everything else about the author, the provenance of this story is puzzling. As far as I have been able to determine, it was written under the title The Healer, was first published in German in 1950 as Macario, and somehow wound up with its current title when it showed up in Fantastic.

Illustrations by Tom O'Sullivan.

One of the few facts known about the author is that he — or she? — lives in Mexico, the setting for most of his — or her? — fiction. This tale is no exception. It takes place when the region was still known as New Spain, during the colonial period.

Macario, a dirt-poor woodcutter, barely manages to feed himself, his wife, and their many children. For most of his life, his greatest dream has been to eat an entire roast turkey by himself. Over several years, his wife saves the tiny payments she receives for doing chores for slightly less poverty-stricken folks. She buys a turkey, prepares it exquisitely, and presents it to her husband, telling him to go into the woods and devour it alone.

Before he can enjoy the delicious feast, however, three strange visitors show up. The first is a sinister fellow, richly dressed. He offers Macario enormous wealth for a share of the turkey. Macario refuses.

The first guest.

The second one is poorly dressed, gentle, and saintly. Despite his kindly manner, Macario again refuses to share his meal. The visitor blesses him anyway.

The second guest.

The third guest, as the title suggests, is the one most vital to the plot. Macario knows he cannot refuse this cadaverous figure, so he at least manages to keep half of the turkey for himself. In exchange, the guest gives him an elixir that will cure all ills, but only if the visitor chooses who will live and who will die. The rest of the story follows Macario as he wins a reputation as a great healer. A summons from the Viceroy of New Spain, whose child is dying, leads to a final confrontation with the third guest.

This is a remarkable fantasy, with the simplicity of a folktale but the sophistication of great literature. It appeared in The Best American Short Stories 1954 (edited by Martha Foley), so I'm not alone in my opinion. It was even made into a Mexican movie in 1960, which you might be able to catch at your local arthouse cinema, if you don't mind subtitles.

Five stars.

The Tanner of Kiev, by Wallace West

The last time we met this author, it was with a reprint of the antifeminist dystopia The Last Man, to which my esteemed colleague John Boston awarded one star. Even if we ignore that story's political stance, it's poorly written. Will this tale, from the October 1944 issue of Fantastic Adventures, be any better? It could hardly be worse.

Cover art by J. Allen St. John.

The first thing to keep in mind is that this is a story about World War Two, written and published during the height of the conflict. You have to expect Our Side to be heroic Good Guys, and Their Side to be sadistic Bad Guys. In particular, the Soviets are definitely on the side of the angels here.

Illustrations by Malcolm Smith.

The hero parachutes behind enemy lines in Nazi-occupied Ukraine. His mission is to deliver a radio transmitter to the underground resistance. Things get weird pretty quickly, as he runs into an immortal magician from Russian folklore.

The wizard and his pets.

Next thing you know, he's at the chicken-legged hut of the legendary old witch Baba Yaga. None of this supernatural stuff seems to bother him, and soon he's on his way into Kiev. He contacts the Russian guerillas, including the pretty female one with whom he falls in love. With the help of the warlock and witch, as well as a talking squirrel and a were-rat, the brave Soviets overcome the craven Germans.

Given the fact that, inevitably, a wartime story is going to paint things in black and white, this isn't a bad yarn at all. It's pretty well written, and the wild and wooly plot held my interest. The changes in mood from whimsical to romantic to horrific are disconcerting, and the love story is a little sappy, but's it worth a read.

Three stars.

Wolf Pack, by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

Cover art by Leo Summers.

The Second World War is also the background for this story, from the September-October 1953 issue of Fantastic, but this time the battle rages in Italy instead of the Soviet Union.

Illustrations by Bernard Krigstein.

The main character is the pilot of an American bomber who has already flown nearly fifty missions, raining destruction from the skies. He has recurring dreams about a alluring woman he thinks of as La Femme, or just La. It would be easy to dismiss this as a predictable fantasy for a young man deprived of female company for an extended period of time, or as an idealized image of his girlfriend back home. Yet she seems very real, and he appears to be in some kind of telepathic communication with her, even while awake.

The woman known as La.

During his latest bombing run, he nearly aborts the mission, terrified that he might destroy her. The other members of the crew have to physically restrain him to complete their gruesome task.

A bomber's world.

The author was a radio operator and tail gunner during World War Two, participating in as many bombing missions over Italy as the story's protagonist. It's no surprise, then, that the details of life as a bomber pilot are extremely realistic and convincing. Miller took part in the bombing of the Benedictine Abbey at Monte Cassino in 1944, which certainly had an influence on the writing of his award-winning novel A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959), already considered a modern classic.

Unlike the previous story, which, understandably, was full of gung-ho patriotic glory (much like Sergeant Sadler's hit song, come to think of it) this is a somber, emotionally powerful account of the way that war turns men into machines, and how the innocent suffer as much as the guilty.

Five stars.

Betelgeuse, in Orion: The Walking Cities of Frank R. Paul, by Anonymous

I wasn't sure if I should even bother discussing this little article, but what the heck. It originally appeared under the slightly different title Stories of the Stars: Betelgeuse in Orion, supposedly by a Sergeant Morris J. Steele in the September 1944 issue of Amazing Stories. This is probably a pseudonym for the magazine's editor, Raymond A. Palmer, but I can't prove that.

Cover art by Julian S. Krupa.

Anyway, after some facts about the giant star, we get wild speculation about the beings who might live there. It's pretty much just a way to fill up some space.

Two stars.

The End of the Search

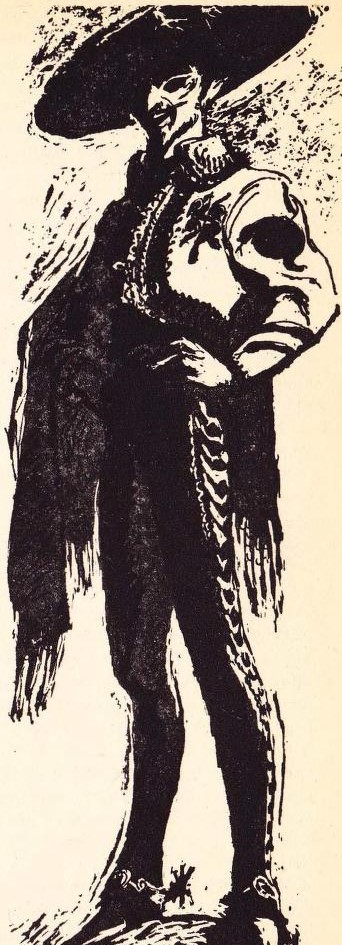

Well, my search for enjoyable fiction certainly paid off! This was an outstanding issue. Even the worst story was pretty good, and the best were excellent. It makes me ponder my skepticism about reprinting old stuff. After all, I don't complain when an movie from yesteryear shows up on television, as long as it's a good one.

Check your local listings to see if this decade-old classic will be showing in your area any time soon.

![[April 8, 1966] Search Parties (May 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Fantastic_v15n05_1966-05_0001-4-672x372.jpg)

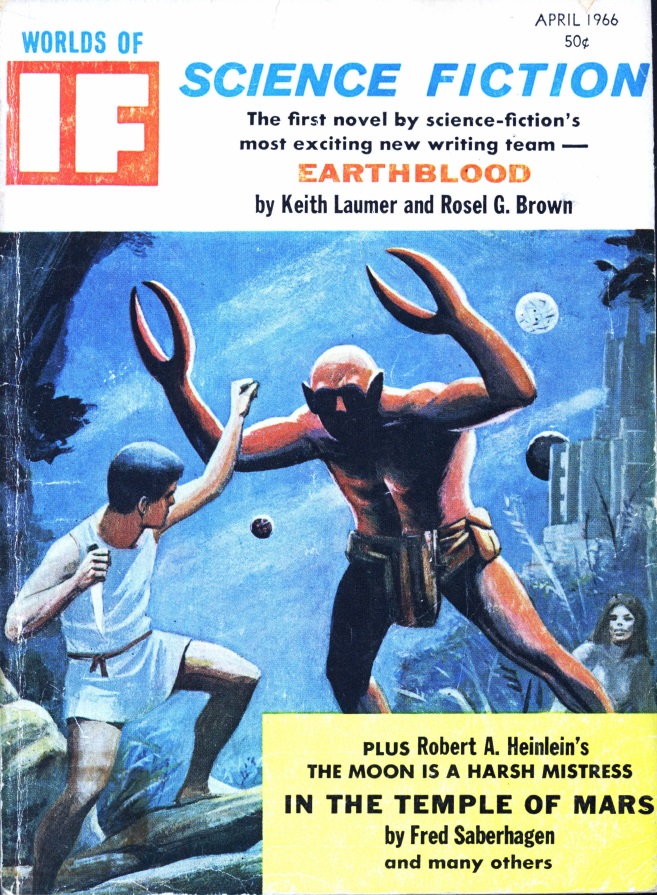

![[April 2, 1966] Hidden Truths (May 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IF-1966-05-Cover-659x372.jpg)

![[March 31, 1966] Shapes of Things (April 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660331cover-500x372.jpg)

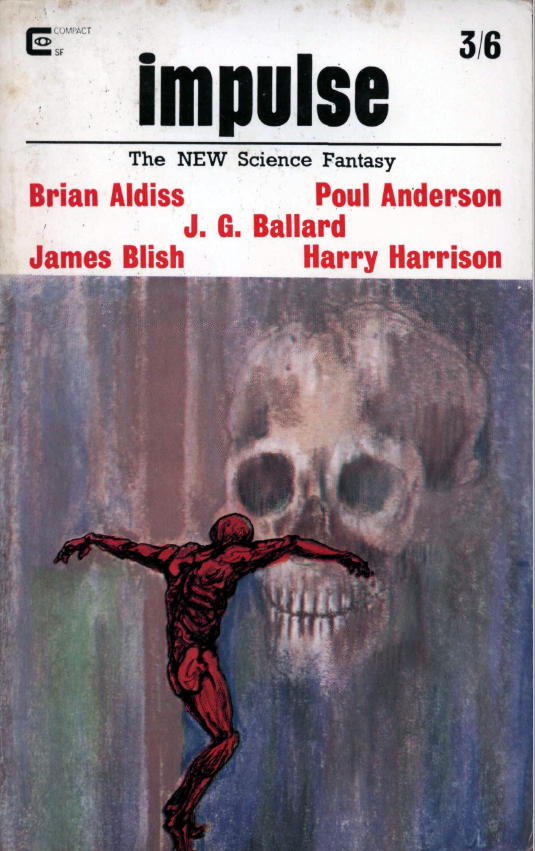

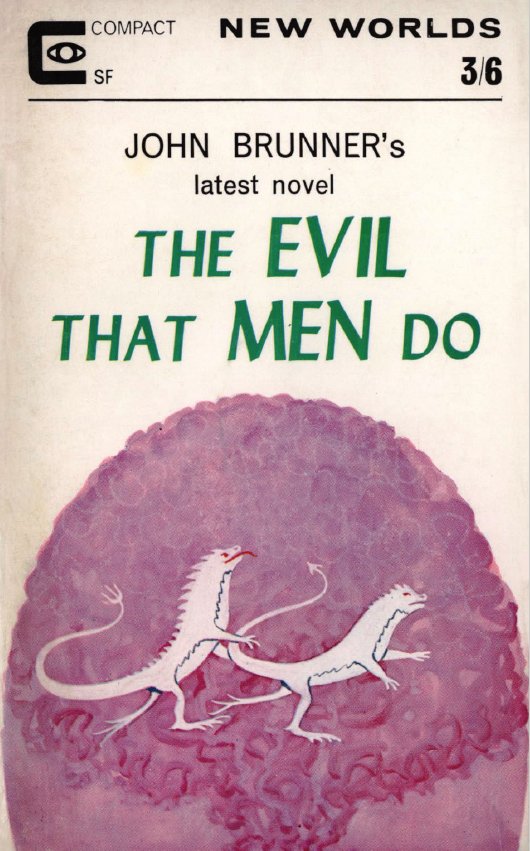

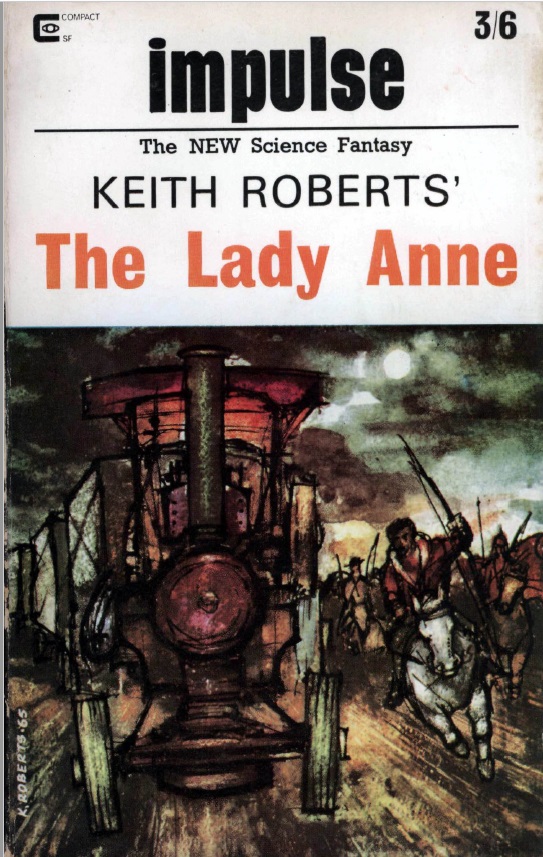

![[March 26, 1966] Steam Tractors and Ballardian Mind Games <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Imp-New-Worlds-April-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[March 22, 1966] Summer in the sun, winter in the shade (April 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/660320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 14, 1966] Random Numbers (May 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n07_1966-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1966] Is More Less? (April 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/amz-0466-cover-448x372.png)

![[March 2, 1966] Words and Pictures (April 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-1-657x372.jpg)

![[February 22, 1966] A New Age? <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, March 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Impulse-NW-March-1966-672x372.png)