by Gideon Marcus

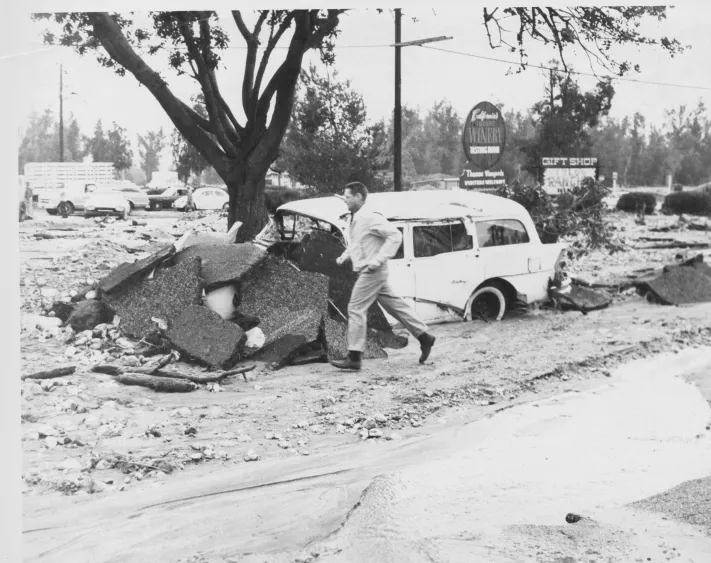

The Bad Kind

For 12 days, 21,000 gallons a day of crude oil spilled into the Pacific ocean off the coast of Santa Barbara. Only on February 8 was the leaking undersea well finally capped. This debacle, courtesy of the Union Oil Co., has blackened the harbors and beaches of the San Gabriel Valley coastline, killing hundreds of sea birds. Even Governor Reagan is declaring this mess a disaster, making federal funds available for cleanup.

Nevertheless, the Governor did not relieve the oil company of its obligation to the government agencies and private citizens harmed by this catastrophe. It will likely take more than 1000 men three weeks to clean up the mess.

The silver lining is that only about 1% of the local seabird population has been affected, and virtually none of the seals. Indeed, the damage is only about a quarter of that caused two years ago when the super tanker Torrey Canyon broke up off the coast of Southwest England.

Still, if the best we can say is that this crisis is not as bad as the worst, I think we can do better.

The Good Kind

In refreshing contrast to the environmental incident described above, the latest issue of Galaxy is anything but a tragedy:

by Douglas Chaffee illustrating The Weather on Welladay

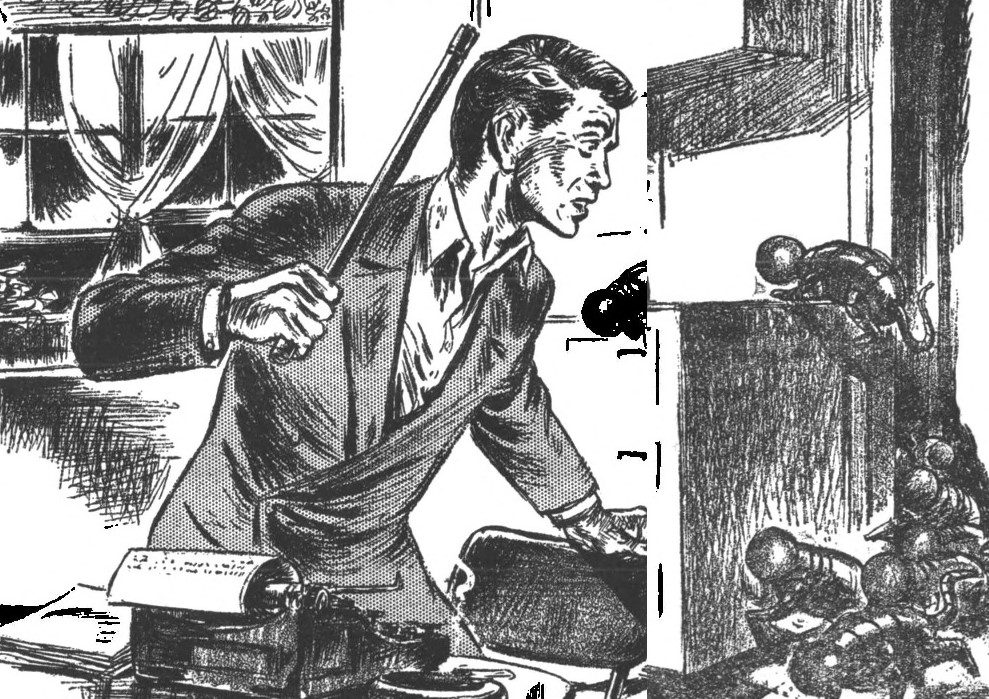

And Now They Wake (Part 1 of 3), by Keith Laumer

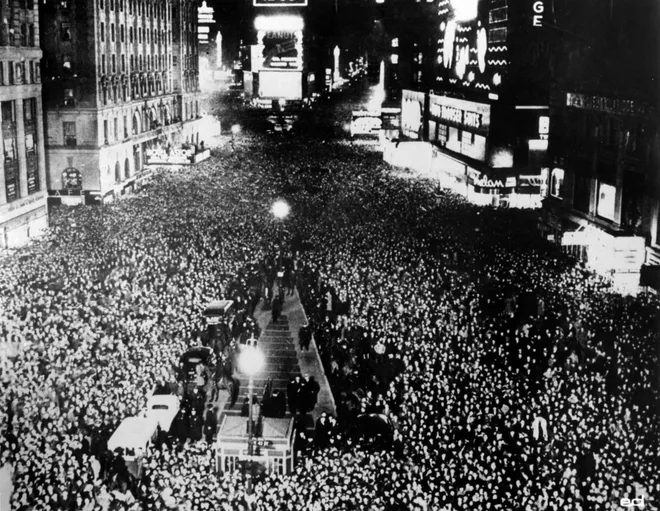

In 1981, just as broadcast power switches on for the first time, an inmate by the name of Grayle makes a daring escape from a New York prison. He is an enigmatic man, an inmate who looks 35, but who has been incarcerated since before World War 2. He also possesses an uncanny ability to heal from wounds.

At the same time, another fellow with similar powers stumbles drunk out of a bar, making his way to a steam room where he miraculously heals a profound set of scars and ejects an antique Minie ball from a wound in his back.

These events are coincident with the appearance of a tremendous water spout in the middle of the Atlantic, and interwoven with tales from a thousand years ago of a renegade from the Galactic Fleet named Thor, and his comrade-turned-betrayer, Loki.

by Jack Gaughan

Who are these two immortals, and why has their story suddenly come to a head? I don't know…but I'm hooked!

Four stars, so far.

The City That Loves You, by Raymond E. Banks

The Alpha Centauri city of Relax offers everything to its twenty million inhabitants—comfort, company, computerized guidance. But what happens when a citizen wants to leave? What if every inducement, soft and hard, is made to keep him there? Does the fellow really have a choice in the matter?

I read the whole story waiting for the other shoe to drop, and I was not displeased with the result. In the end, for a place to truly be paradise, there must be a way out. The socialiast utopias of the world, from Bulgaria to Beit Ha Shita, might take note.

Four stars.

Leviathan, by Lise Braun

An advanced submarine, akin to the Seaview from Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea rescues a primitive fisherman lost at sea in the Atlantic Ocean. This inadvertently gives rise to a number of familiar legends.

This is an old-fashioned story; it would have been right at home in Imagination in 1954. I do like the clever, organic way Braun conveys that the action takes place thousands of years in the past, and the reading is pleasant, if not extraordinary.

Three stars.

The Weather on Welladay, by Anne McCaffrey

by Reese

The sodden, storm-lashed world of Welladay seems too bleak a world for settlement. However, schools of whales that inhabit it produce a valuable radioactive substance prized for medical applications. A team of hardy fishermen taps these whales for their lymphic treasure, braving the waves and weather.

But some pirate has been draining the whales dry, decimating the population and threatening the economy and health of the Federation. Is it one of the four fishers? The mysterious woman space pilot shot down at the beginning of the tale, who crashes on a lonely archipelago? Or someone else?

This is definitely one of McCaffrey's better stories, with far more atmosphere (no pun intended) and far less barely suppressed violence and hokey romance. It goes on a little long, and I find it improbable that this vast planet seems to have exactly six people on it, but I enjoyed it.

Three stars.

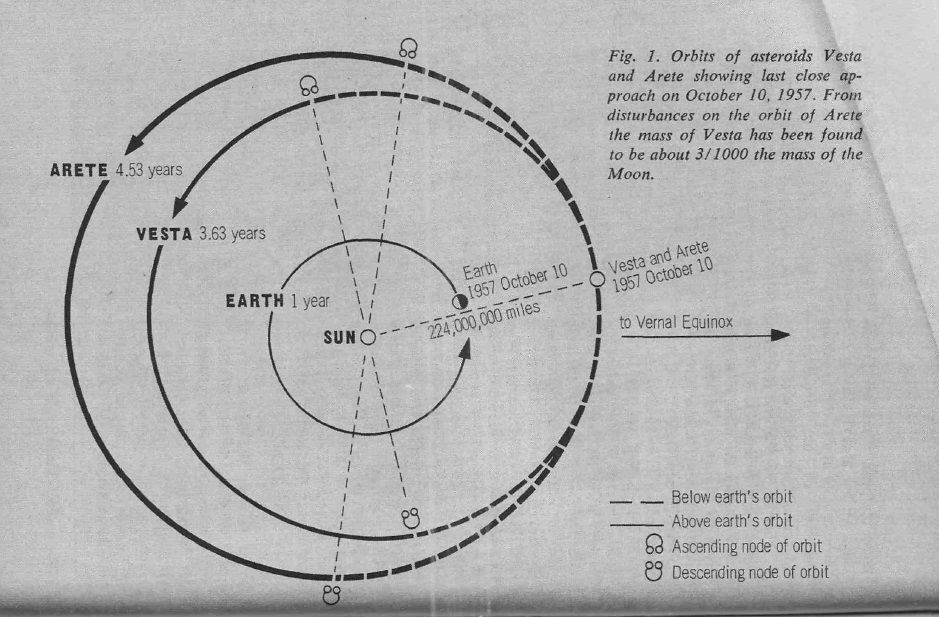

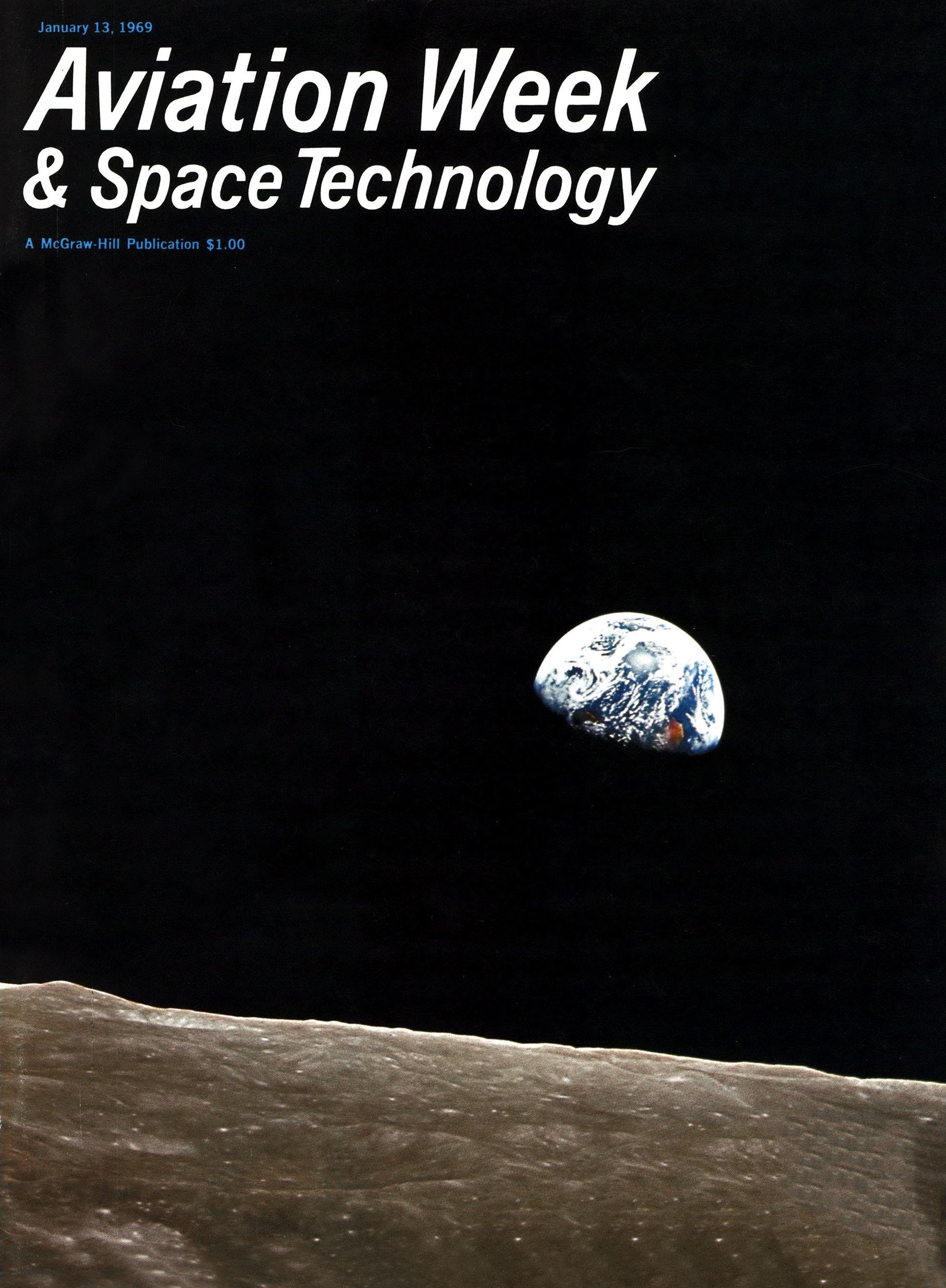

For Your Information: Collision Course, by Willy Ley

Mr. Ley's piece this month is on asteroids that cross Earth orbit, particularly Icarus, which precipitated the 49th end-of-the-world scare since the birth of Christ.

Interesting and useful, though rather brief.

Three stars.

The Last Flight of Dr. Ain, by James Tiptree, Jr.

A sick scientist and his dying love make a multi-stop air flight around the world. At each landing, he makes sure to expose as many people as possible to what appears to be an aerosol for cold symptoms, and he feeds bread crumbs to migratory birds. As the story unfolds, told mostly in third-party reports, we learn the scientist was working on a deadly disease, and that he thinks of humanity as a blight on the Earth.

There's no subtext to the story—it's all on the surface—but it's beautifully told and very eerie. I liked it; my favorite from Mr. Tiptree so far. Four stars.

The Theory and Practice of Teleportation , by Larry Niven

Adapted from a lecture Niven gave at Boskone in front of the MIT Science Fiction Society, this is an interesting look at the effects of teleportation, in all its potential developmental paths, on society.

Four stars.

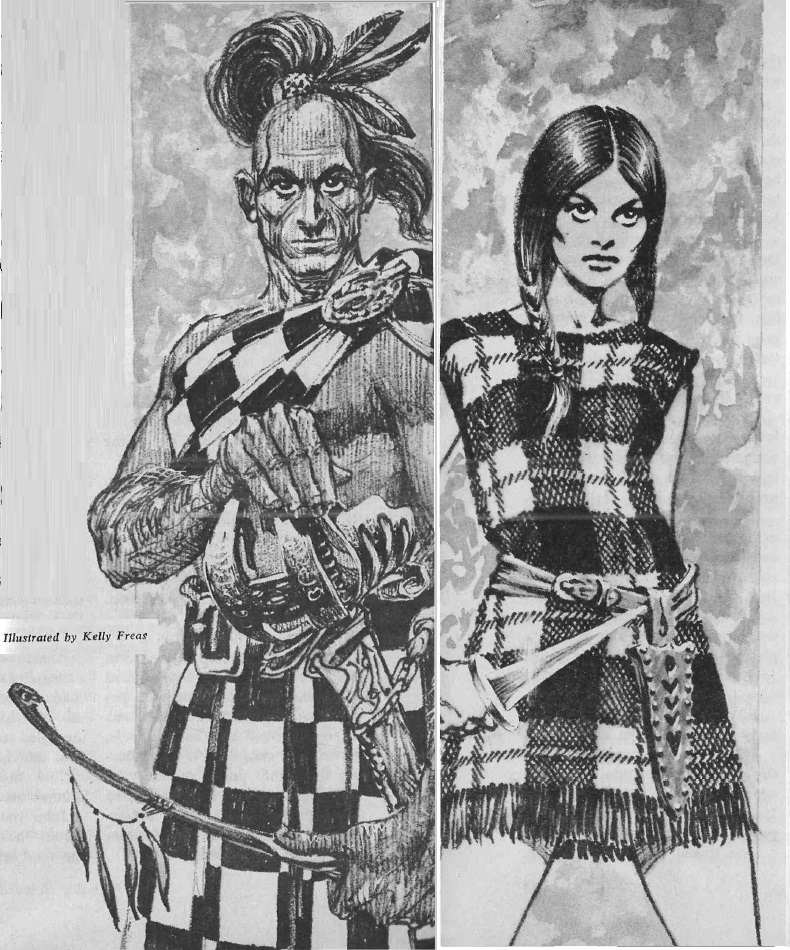

Greeks Bringing Knee-High Gifts, by Brian W. Aldiss

A darkly humorous story set in the near future, satirizing the world of executives. They all hate each other but are not allowed to express it or complain, so they do things that they can claim are generous as an act of passive aggression.

For instance, one gifts another with a genetically tailored midget Tyrannosaurus…which promptly eats the recipient's leg. Said giftee then names the dinosaur after the giftor's coquettish wife and turns up at the giftor's funeral with the creature to terrorise people, but in doing so claims it is a lovely tribute.

Rather obtuse and pointless. I didn't like it.

One star.

(with thanks to Kris for co-writing this review-let).

Godel Numbers, by J. W. Swanson

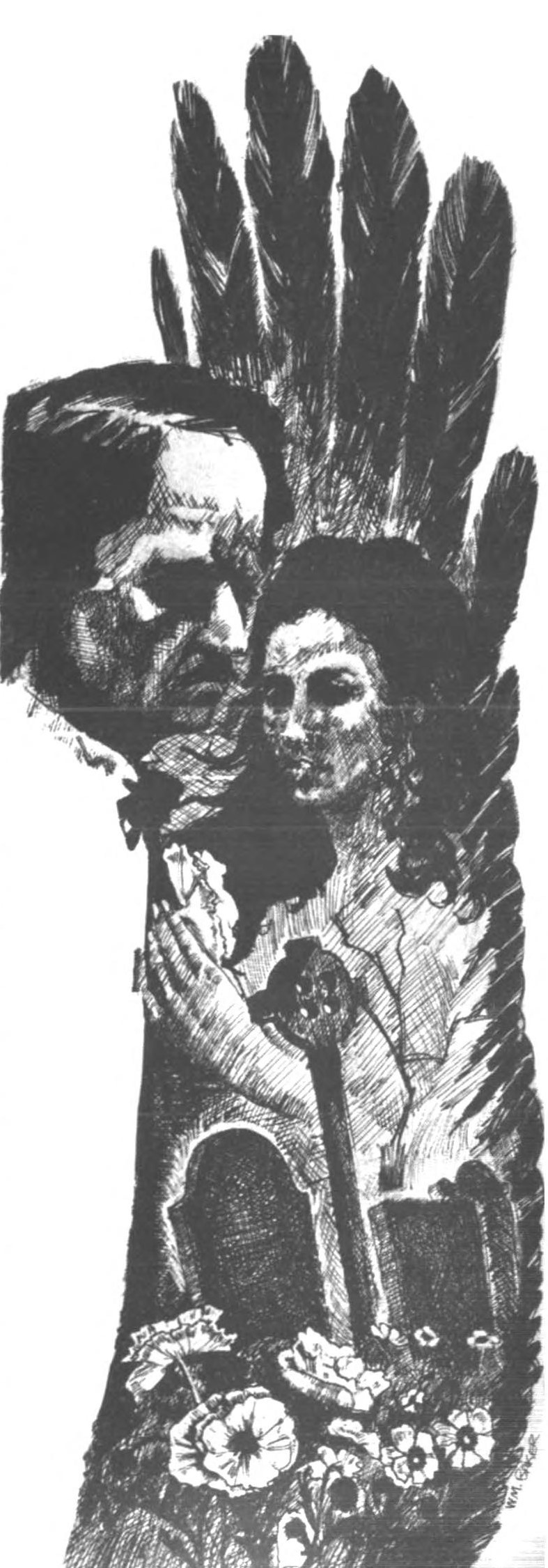

by Jack Gaughan

200 miles west of Cairo, archaeologists have dug up what they're calling the "Cairo Stone". It is a black tablet, obviously artificial, clearly advanced, and meticulously carved with a series of scratch marks. Dated to 3000 B.C., it could not have been made by a contemporary terrestrial civilization. It's up to three scientists, a melange of linguists and computer engineers, both to crack the code of the tablets and to fend off Soviet agents.

In the end, the tablet serves much the same purpose as the monolith(s) in 2001, jump-starting humanity's progress. It's an amiable, old-fashioned sort of tale, and so esoteric that it probably would have done well, if not better, in Analog.

Three stars.

Cleaning up

All in all, the latest Galaxy makes for pleasant, if not outstanding, reading. I would certainly much rather read about Godel numbers, teleportation, immortals, and isotopic pirates than oil slicks any day!

![[February 12, 1969] Slick stuff (March 1969 <i>Galaxy</i> science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690212cover-662x372.jpg)

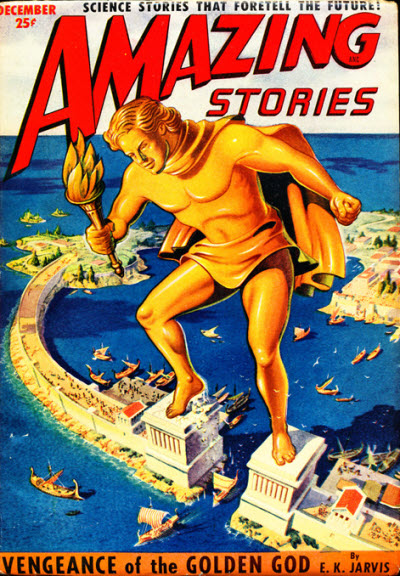

![[February 8, 1969] So Much for That (March 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/amz-0369-cover-492x372.png)

![[February 2, 1969] Winners and Losers (March 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/IF-1969-03-Cover-574x372.jpg)

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on

Counter-protesters armed with sticks and iron bars attack civil rights marchers while the police look on The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan

The Steel General rides again. Art by Best Professional Artist Jack Gaughan![[January 28, 1969] Slidin' (February 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690128cover-672x372.jpg)

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

![[January 26, 1969] A New World Order <i>New Worlds</i>, February 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/New-Worlds-Feb-1969-672x372.jpg)

Impressively startling cover by Gabi Nasemann.

Impressively startling cover by Gabi Nasemann. As expected, the usual nudity, not entirely related to the prose. Artwork by Gabi Nasemann.

As expected, the usual nudity, not entirely related to the prose. Artwork by Gabi Nasemann.

Artwork by Gabi Nasemann.

Artwork by Gabi Nasemann.

Table made up by J. G. comparing different writers. Notice the positioning of Pohl and Asimov and that of Burroughs (presumably William S., not Edgar Rice!), a sign of where this magazine seems to be going.

Table made up by J. G. comparing different writers. Notice the positioning of Pohl and Asimov and that of Burroughs (presumably William S., not Edgar Rice!), a sign of where this magazine seems to be going. Artwork by Haberfield.

Artwork by Haberfield. Artwork by John T. Sladek.

Artwork by John T. Sladek.

Work by Mervyn Peake.

Work by Mervyn Peake. Artwork by Prigann.

Artwork by Prigann. Artwork by Prigann.

Artwork by Prigann.

Artwork by Gabi Nasemann and Charles Platt.

Artwork by Gabi Nasemann and Charles Platt.

An advertisement from this issue of Peake's better-known work.

An advertisement from this issue of Peake's better-known work.

![[January 18, 1969] (February 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690118cover-663x372.jpg)

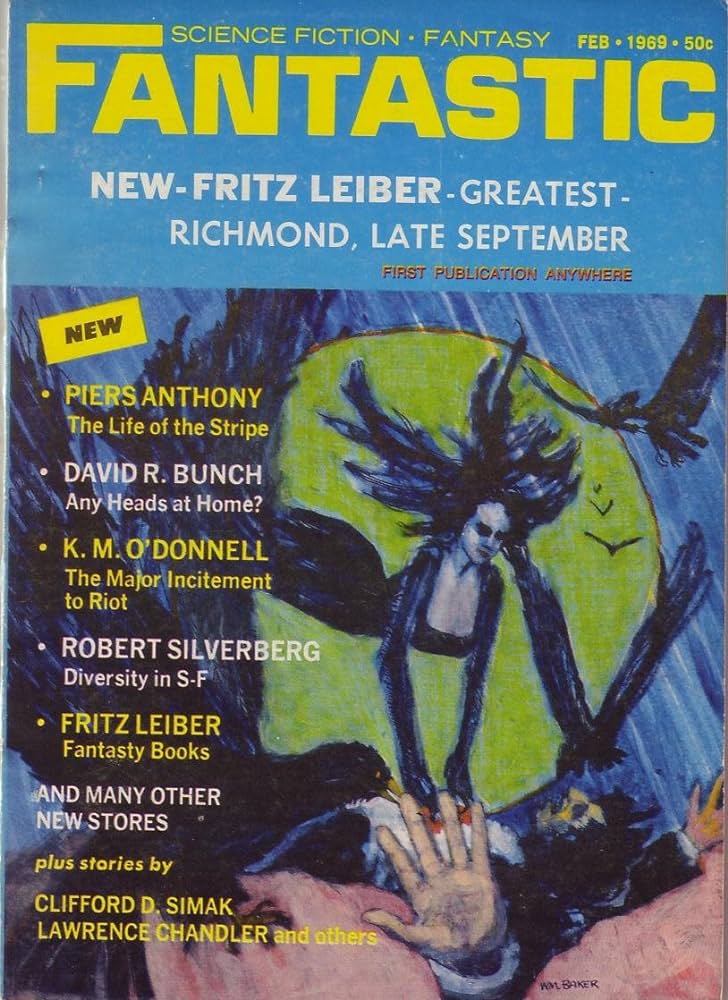

![[January 8, 1969] Young Punks and Old Fogies (February 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690108cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1969] Booms and Busts (February 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690106cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1969] Not following through (February 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IF-1969-02-Cover-570x372.jpg)

The March of the One Hundred Thousand. The banner reads “Down with dictatorship. People in power.”

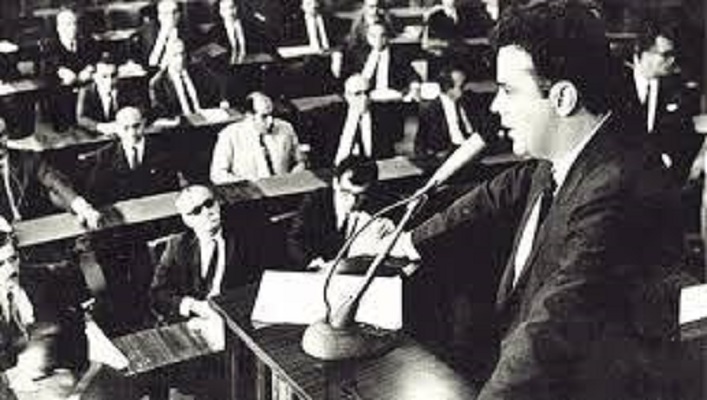

The March of the One Hundred Thousand. The banner reads “Down with dictatorship. People in power.” Márcio Moreira Alves delivering the speech that got him into trouble.

Márcio Moreira Alves delivering the speech that got him into trouble. Time travelers on their way to meet their ancestor. Art by Vaughn Bodé

Time travelers on their way to meet their ancestor. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[December 31, 1968] Auld Lang Syne (January 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681231cover-672x372.jpg)