Don't miss tonight's Spocktacular edition of Science Fiction Theater! Starts at 7PM Pacific. Also featuring the last appearance of Chet Huntley on the Huntley/Brinkley Report!

by Gideon Marcus

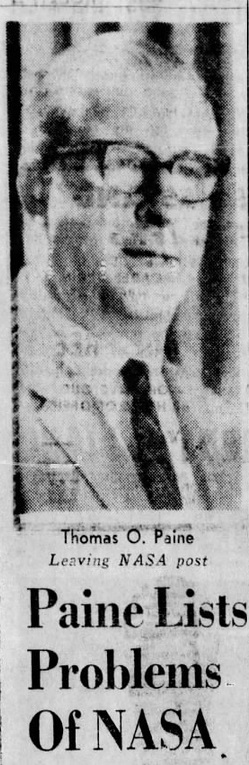

Paine-ful exit

The proverbial rats are leaving the sinking ship. Not too long ago, a clutch of NASA scientists departed America's space agency, citing too much emphasis on engineering and propaganda. Now, Thomas O. Paine, who took NASA's reins from its second adminstrator, Jim Webb, has announced his resignation. He leaves the agency on September 15. He lasted less than two years; contrast with Webb, who was there seven and a half.

Paine did not characterize his departure as any indication of disagreement with the agency's current direction. He said he was leaving NASA in strong shape, and that this was the most appropriate time for his departure. He's going back to a management position with General Electrics.

But Paine cannot be very happy with how things have been going lately. NASA's work force has been gutted–from 190,000 to 140,000 personnel; the last Saturn V first stage will be completed next month; and the future of Apollo's successor, the Space Shuttle, is in doubt. The poor director has watched the space agency go from the pinnacle of human achievement to a nadir unseen since the late '50s. If only we'd adopted the Agnew "Mars Plan"…

Deputy Administator George M. Low will take Paine's place for the time being. A replacement has not yet been tapped. Stay tuned!

Painful effort

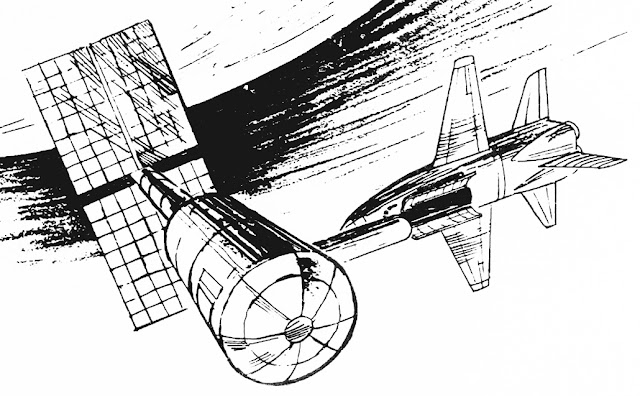

If Paine left willingly, Analog editor John Campbell, on the other hand, seems determined not to let his magazine go until he does. Which is sad because this month's issue is yet another indication of how far the once-proud property has fallen in quality."Two astronauts meet one another between a large satelite.

Cover by Kelly Freas

Continue reading [July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 Analog)

![[July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28,1970] Cinemascope: Cry Me A River (Cry of the Banshee) and Games in Goatskin (Dionysus in ‘69)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700728posters-492x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1970] Solace for Your Trillion-Year-Old Spirit (George Malko's <i>Scientology: The Now Religion</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Scientology-672x372.png)

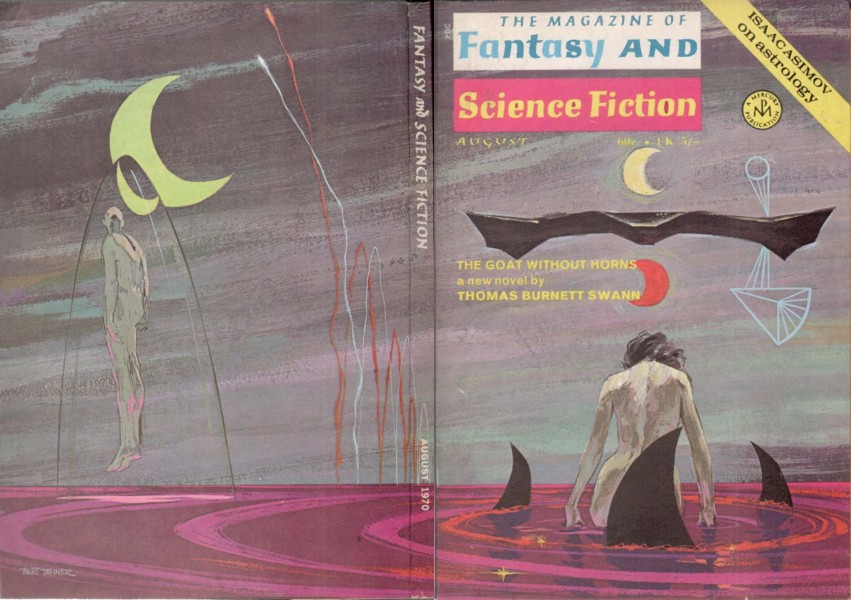

![[July 20, 1970] The Goat without Horns…among other things (August 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700720fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

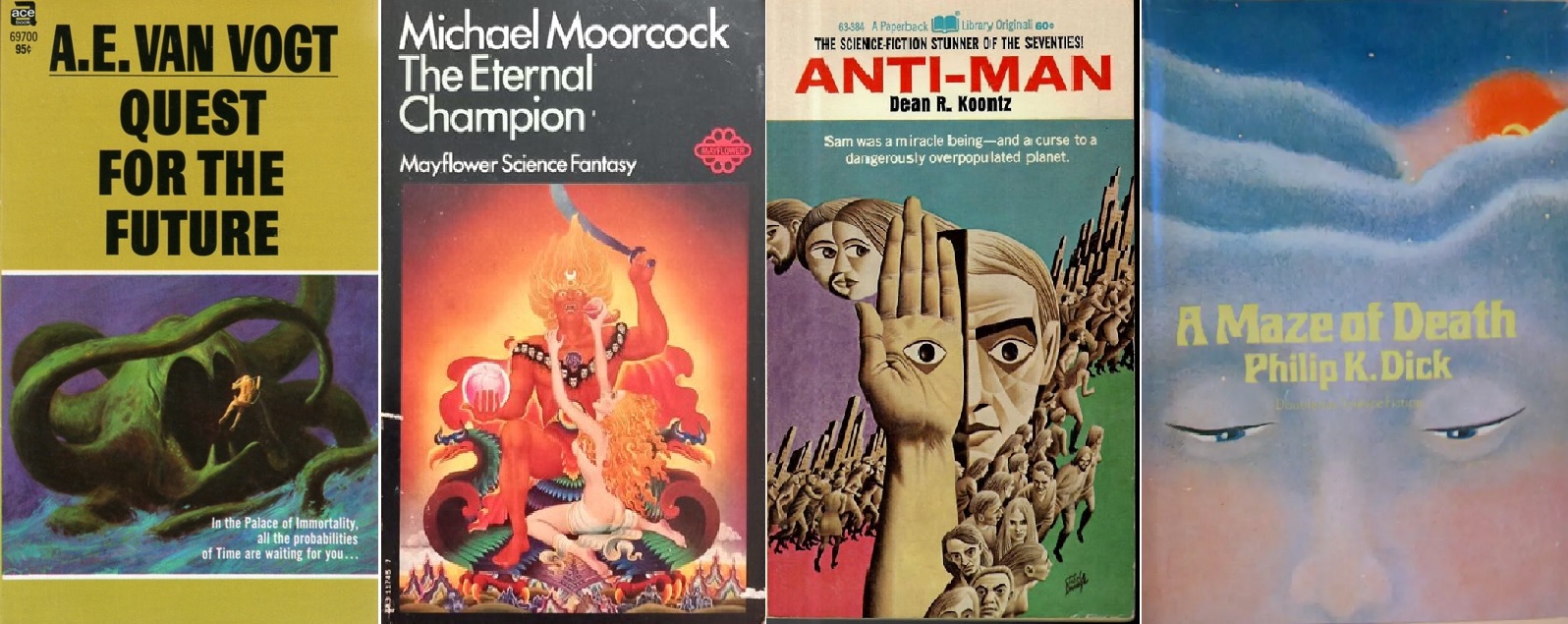

![[July 19, 1970] Dips in road (<i>Maze of Death</i>, <i>The Eternal Champion</i>…and others—July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700719covers-672x372.jpg)

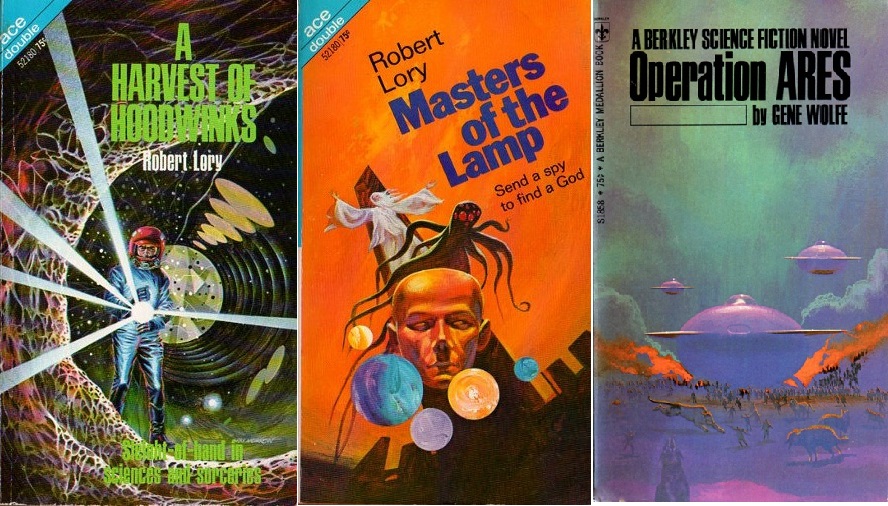

![[July 18, 1970] Two-star three step (July 1970 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700718covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1970] Journey Behind the Iron Curtain, Journey into Space](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/otherother-672x372.jpg)

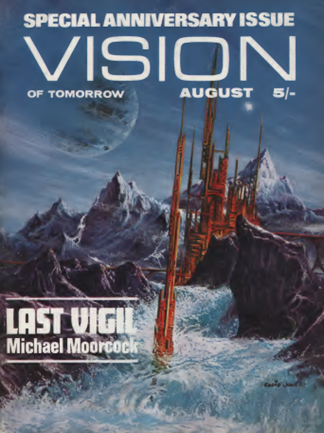

![[July 14, 1970] Hit For Six (<i>Vision of Tomorrow #11</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/VOT3-324x372.png)

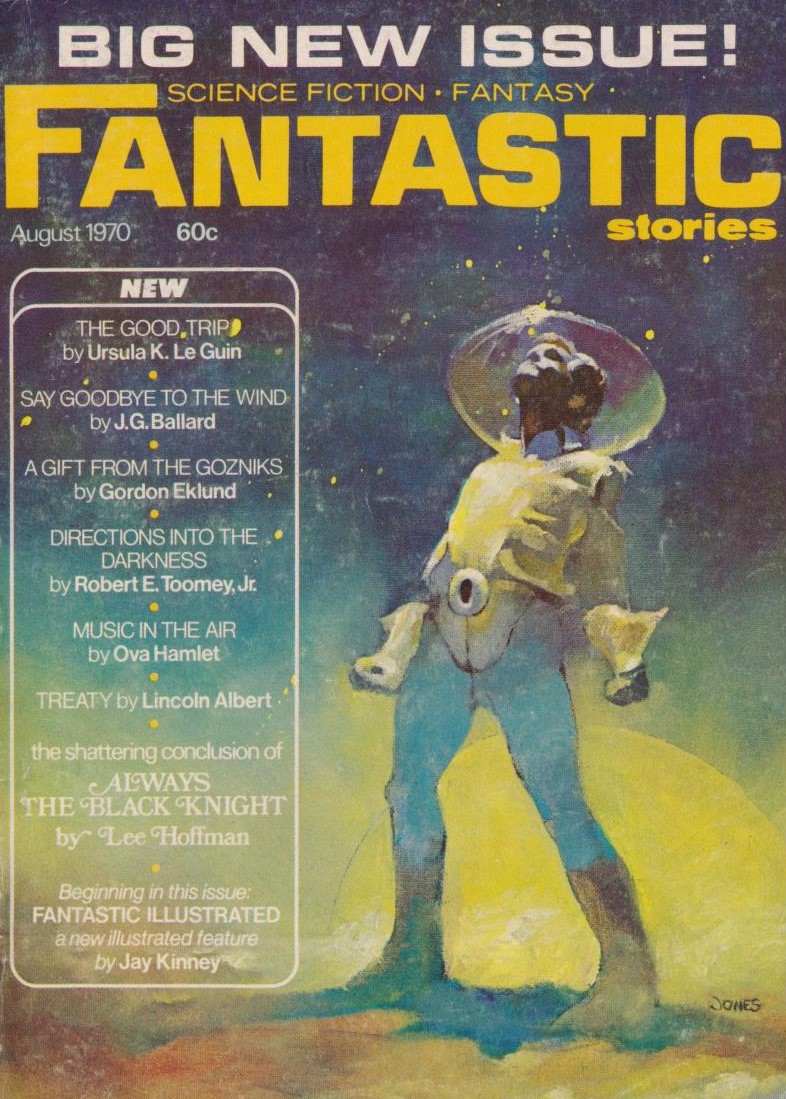

![[July 12, 1960] The New Generation (August 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/COVERSMALL-672x256.jpg)

![[July 8, 1970] I'm Still Marching Some More (<i>Orbit 7</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Orbit-C-416x372.jpg)