by David Levinson

Voyages into the known

Readers over 30 may remember Thor Heyerdahl and his Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947. He hoped to prove that the Pacific islands had been reached from South America before Polynesians got there from the west. The balsa log raft he built eventually ran aground in the Tuamotu archipelago in French Polynesia, demonstrating that such a voyage was at least possible. However, most archaeologists and anthropologists consider it far more likely that any contact between Polynesia and the Americas (there is some highly inconclusive evidence) was initiated by the Polynesian people, who have a proven track record of crossing vast distances into the unknown.

In any case, Heyerdahl has inspired a number of imitators hoping to travel farther, including some attempts to travel west to east. On May 29th, Spanish sailor Vital Alsar Ramirez started his second attempt to sail from Ecuador to Australia. The first attempt in 1966 failed after 143 days when the raft was rendered no longer seaworthy by teredo worms.

The new raft, dubbed La Balsa, has one major improvement over the Kon-Tiki: a moving keelboard. This will allow the raft to be steered toward more favorable currents, where Kon-Tiki could only drift with assistance from the simple square sail. Such keelboards are known to Ecuadoran natives and so are a perfectly reasonable addition. Best of luck to the four men aboard.

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea.

Speaking of Thor Heyerdahl, his current interest is in demonstrating that ancient Egyptians could have reached the Americas in reed boats. His first attempt last year aboard the Ra got within about 100 miles of the islands of the Caribbean before it became so waterlogged it began to break apart. Now he’s giving it another go.

The Ra II features a tether to keep the stern high, which should help keep the boat from suffering the fate of its predecessor. This is something the original ought to have had; such tethers are clearly visible in ancient Egyptian depictions of reed boats. The crew also plan to take marine samples along the way to study ocean pollution. The Ra II set out from Morocco on May 17th.

Of course, as with the Kon-Tiki, proving that such a voyage could have been made won’t prove that it was. The Egyptians were never great sailors, generally contracting ocean navigation out to more maritime cultures of the eastern Mediterranean. Still, best of luck to Heyerdahl and his crew as well.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

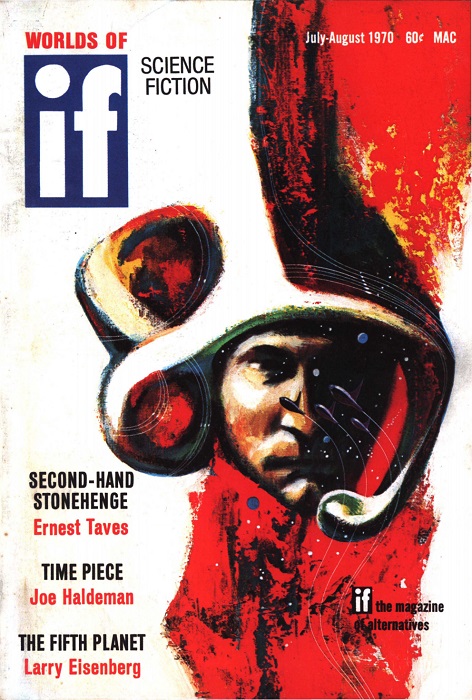

Polishing the family silver

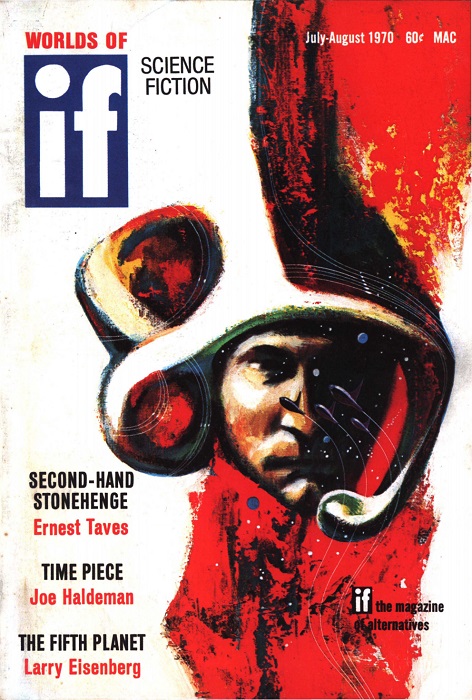

Science fiction has a lot of tried and true plots, some better than others. But good writing can occasionally make a hackneyed, sub-par plot something better, and bad writing can turn an intriguing concept into a slog. Fortunately, this month’s IF has a lot more of the former.

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Continue reading [June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 IF) →

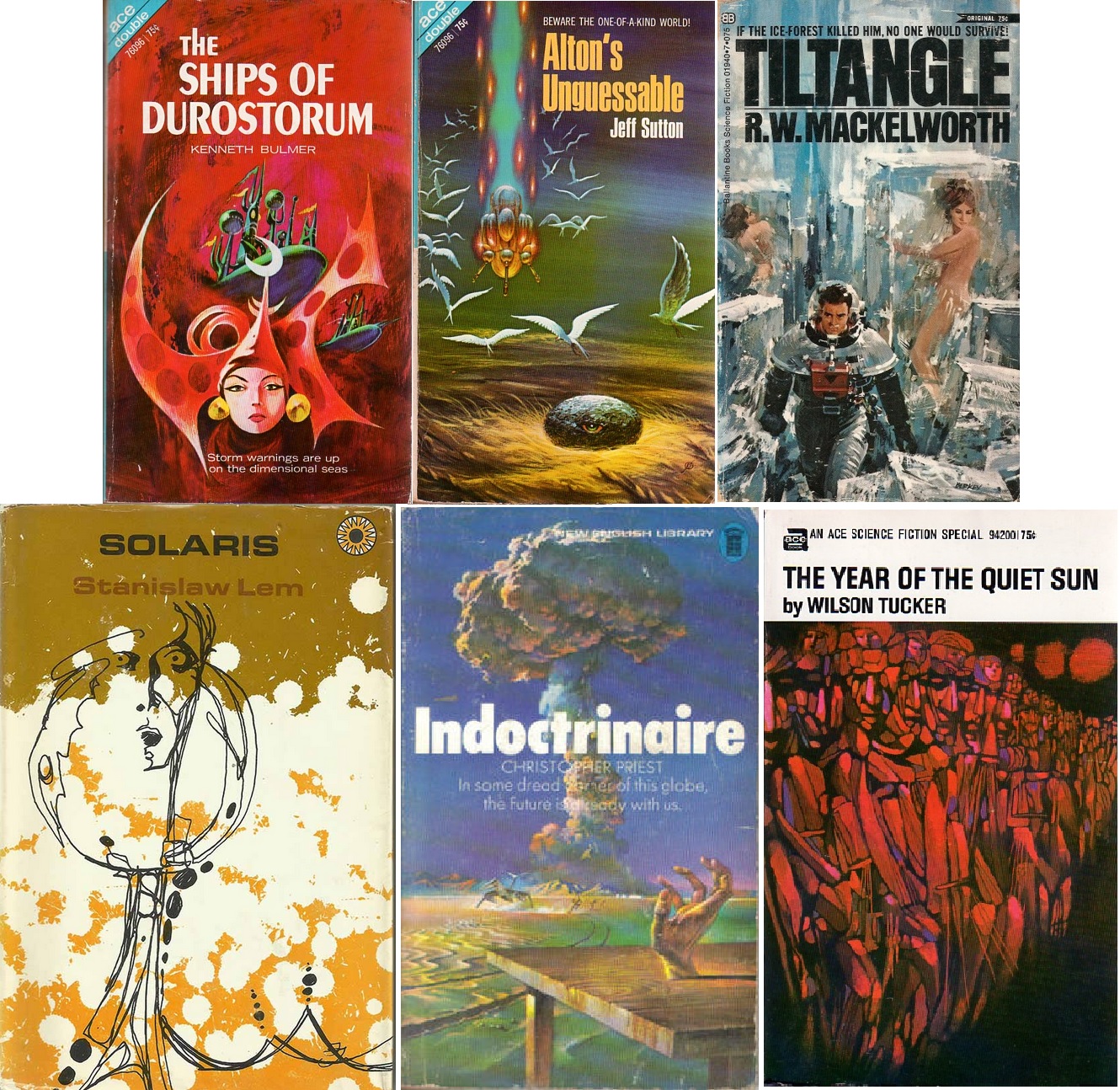

![[June 16, 1970] <i>Solaris</i>, <i>Year of the Quiet Sun</i>…and a host of others (June 1970 Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1970] Talkin' Loud, Swingin' Soft (June 1970 <i>Watermelon Man, The Landlord, and Cotton Comes to Harlem</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700614movies-672x372.jpg)

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

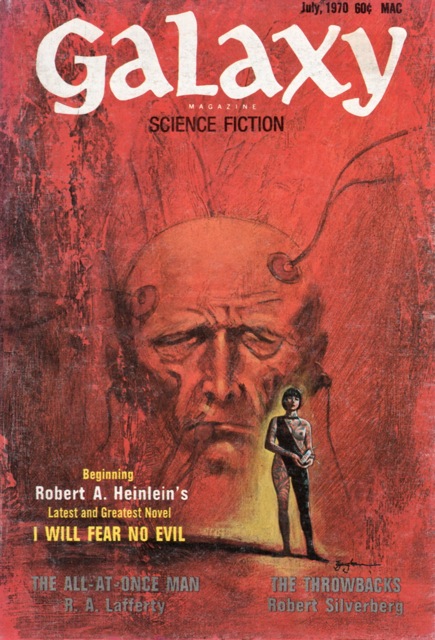

![[June 10, 1970] I will fear <i>I Will Fear No Evil</i> (July 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700610galaxycover-435x372.jpg)

![[June 8, 1970] Beneath the Planet of the… Mutants? (Not Apes)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/beneath1-565x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan![[June 2, 1970] Turning Up The Heat (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Inferno)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700603abitundertheweather-672x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 28, 1970] A pair of Saras: <i>Flower of Doradil</i> and <i>A Promising Planet</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ace_double-672x372.png)