by Gideon Marcus

The Big Bang

The Americans and Soviets have signed onto a Partial Test Ban Treaty, restricting nuclear tests to deep underground. The Chinese and French are under no such obligation, however. Not only have the Chinese detonated two (or was it three?) atomic devices in the open air, but now the French have begun their own series of above-grown tests.

These big bombs are being burst on the French Polynesian atoll of Moruroa. I don't know what the indigenous South Seas population thinks of the blasts, but I imagine their opinions will sour as quickly as their strontium-90 laced milk.

The Big Fizzle

by Gray Morrow

The French may be making a big noise in the Southern Hemisphere, but Fred Pohl, editor of IF, Worlds of Tomorrow, and the formerly august Galaxy, has barely been squeaking by. Indeed, the August 1966 issue of Galaxy is the most feeble outing I've read in a long time.

The Body Builders, by Keith Laumer

by Nodel

Opening things up, Keith Laumer extrapolates a future that is a straight-line evolution of our current boob tube culture. Since so many of us are content to live vicariously, eyes plastered to the small screen, why not take things a few steps further? And so a large portion of humanity lives flat on their backs, plugged into life support machines. Their senses are hooked into humanoid surrogates of plastic and metal, optimized for task, emphasized for beauty.

Our protagonist is a prize fighter, or at least, he remote controls a synthetic boxer. Another artificial being provokes our hero into a duel while he's inhabiting his sport model body rather than his brawler suit. So he goes on the lam. Troubles, high jinks, and happy endings ensue.

Elements remind me of Robert F. Young's Romance in a Twenty-First Century Used-Car Lot (shuttling around in personally molded chassis) and Steel (human boxer steps into the ring against a robotic opponent), but this is a nice new spin.

Three stars.

Heresies of the Huge God by Brian W. Aldiss

A giant creature, thousands of miles long, crashes into the Earth. Its bulk causes tremendous damage, alters our seasons, and thoroughly discombobulates our society. This after-the-fact chronicle of the millennium following the alien's arrival is both unsettling and rather funny.

Four stars.

For Your Information: Scheherazade's Island by Willy Ley

This month's science column details the unusual creatures that inhabited Madagascar until quite recently: Big birds, giant lemurs, and other exotics. They may, indeed, yet live there in remote areas of the enormous island.

Interesting topic but bland presentation. Three stars.

The Piper of Dis by James Blish and Norman L. Knight

by Gray Morrow

Authors Blish and Knight return us to the overcrowded world of 2794 on which ten trillion humans live. In this installment, the asteroid Flavia is headed toward Earth, where it will cause tremendous damage. Millions of North Americans must be evacuated to the spare town of Gitler. There are two wrinkles: 1) a convention of the Jones family is currently occupying the city, and they must be evacuated out before refugees can be evacuated in; 2) an insane criminal member of the Jones family, Fongavaro, doesn't want anyone in the city lest he be extradited back to his home in Madagascar.

Actually, there's another wrinkle: it's a dreary potboiler of a story in an implausible world. I hope this is the last piece in the series.

Two stars.

Among the Hairy Earthmen by R. A. Lafferty

What if the Renaissance was really the work of bored aliens? In this typically whimsical piece, a band of seven humanoid cousins arrive at medieval Europe and make history their plaything.

This one of those tales that's all in the telling, and the telling is pretty charming. Three stars.

The Look, by George Henry Smith

Women, hare-brained slaves to fashion that they all are, succumb to trends so horrendous that no man can bear to look at them. It's the plot of a pair of homosexual fashion designers to ensure they have all of mankind to themselves. Or so we're meant to think. The "twist" is that it's actually a ploy of Alpha Centaurians to depopulate the Earth.

If we had a negative counterpart to the Galactic Stars, this would win the prize. One star.

Heisenberg's Eyes (Part 2 of 2) by Frank Herbert

by Dan Atkins

Last issue, we were treated to the first half of Frank Hebert's latest short novel. It takes place in a far (like tens of thousands of years from now far) future in which the human race has completely stagnated in technology, society, and biology. The "Optimen", sterile ubermenschen who are essentially immortal, rule over the mostly sterile humans whose offspring are all produced out of womb and with scrupulous surgical control.

Last installment, the Durant couple had stolen their embryo from under the noses of the Optimen with the help of the Cyborgs, a competing sub-race of humanity that has traded their emotions for computerized sturdiness. The Durant embryo, due to some unexplained quirk, is the first bog-standard human to be spawned in millennia. Able to reproduce, it may hold the key to toppling the static society of humanity.

This installment begins with the Durants stealthily escaping the megalopolis of Seatac. This takes up most of the part, and is ultimately pointless as the triumvirate of rulers is aware of their attempt the entire way. The Durants, their assisting Cyborgs, as well as Svengaard, the surgeon they had taken hostage, are summoned before a full council of the Optimen for punishment. Violence breaks out. Two of the triumvirate are killed. Calapine, the impulsive, simpering woman of the ruling trio, is both outraged and excited by the new feeling of mortality. Nevertheless, she is committed to destroying her captives before they destroy the current order.

Until it is pointed out that the order is just its own kind of death, a sentence of eternal boredom. In any event, it's doomed to failure since even the immortals need increasing doses of enzymes to stay alive, a situation that is quickly becoming untenable.

There is a solution! It turns out that being implanted with an embryo produces all the enzymes one needs to stay alive indefinitely. So women (and men) can be installed with pre-tykes that are made to gestate for thousands of years, and that will keep them alive forever. Thus, humanity can return to some sort of natural (if prolonged) rhythm.

Never minding the utter implausibility of, well, everything about this book, all of the above could probably have been written in about 20 pages. But when you're paid by the word, and you're one of the hottest authors in the genre (I can imagine a half century from now that Dune will replace The Bible as the most-read book in the world; there ain't no justice), I suppose sentences must flow.

Two stars for this part, two and half for the whole book.

Who Is Human? by Hayden Howard

by Jack Gaughan

Starting in medias res, we have the latest story of the Esks: people who look like Eskimos, but are actually born in a month and raised to adulthood in five years. In this installment, which really does not stand alone as a separate story, we learn that the Esks have been artificially created by alien visitors. We are meant to believe that 1) the Esks pose an intolerable risk to the human race as we will soon be outbred and replaced by them, and 2) no one will actually believe our protagonist, Dr. West, when he explains the true nature of the Esks. Everyone maintains they're just plain ol' Eskimos.

This is the silliest, most contrived set of premises. The Esks are already starving due to overpopulation, and thus applying for relief. Once free food starts being doled out, the unnatural increase in population will be known. This may spell adversity for the real Inuit (and the Canadian budget) but it hardly threatens world domination. And it's not like we have a Puppet Masters situation here; the Esks don't possess other humans. They just live alongside them.

Maybe there will be a better explanation down the road. Two stars.

Summer Slump

It's a pretty sad affair when Galaxy clocks in at a bare 2.5 stars. On the other hand, as Michael Moorcock informed us last month, it is not uncommon for magazines to save their weakest material for the summer, when readership is at its lowest. Let us hope that's what is going on here!

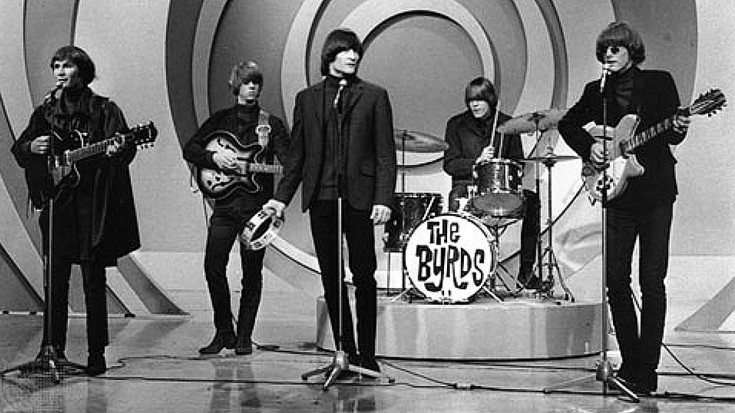

Ah well. At least the summer music is good:

Tune in to KGJ, our radio station!

![[July 8, 1966] South Pohl (August 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660708cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1966] Not Reading You (July 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660630analog-500x372.jpg)

![[June 23, 1966] Interlude, with panthers](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660623bp1-643x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1966] Calm Spots (July 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660616cover-672x372.jpg)

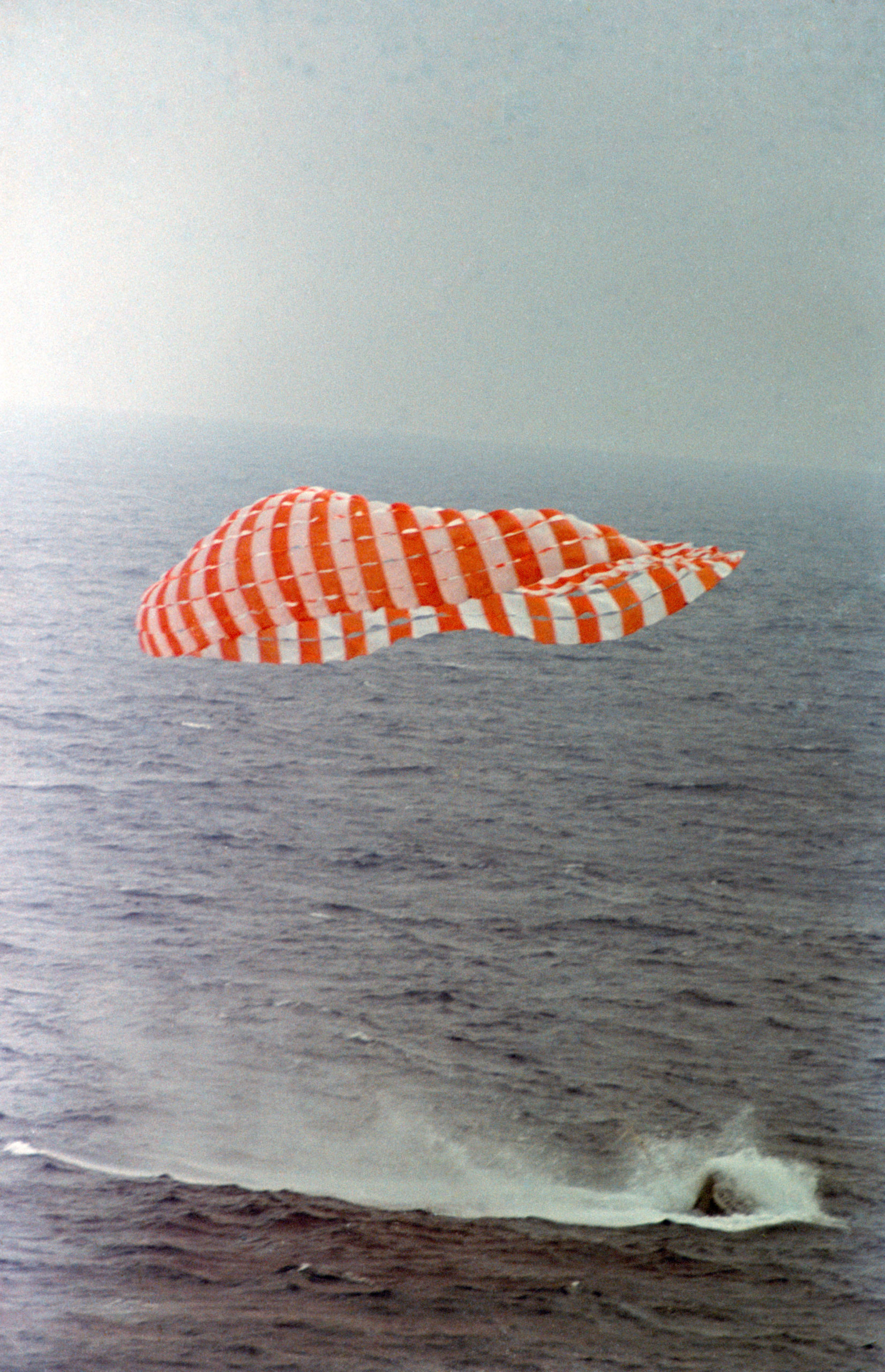

![[June 8, 1966] Pyrrhic Victory (the flight of Gemini 9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/s66-28075-672x372.jpg)

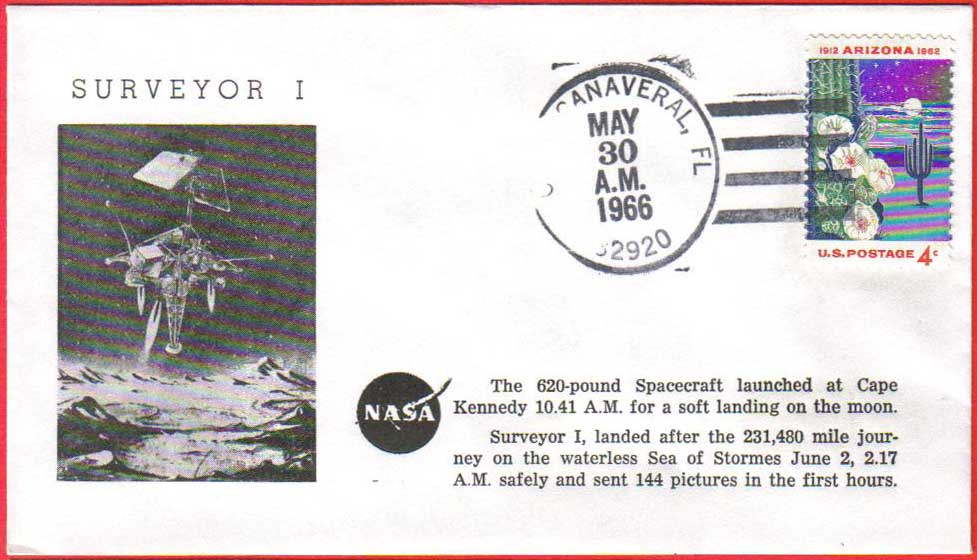

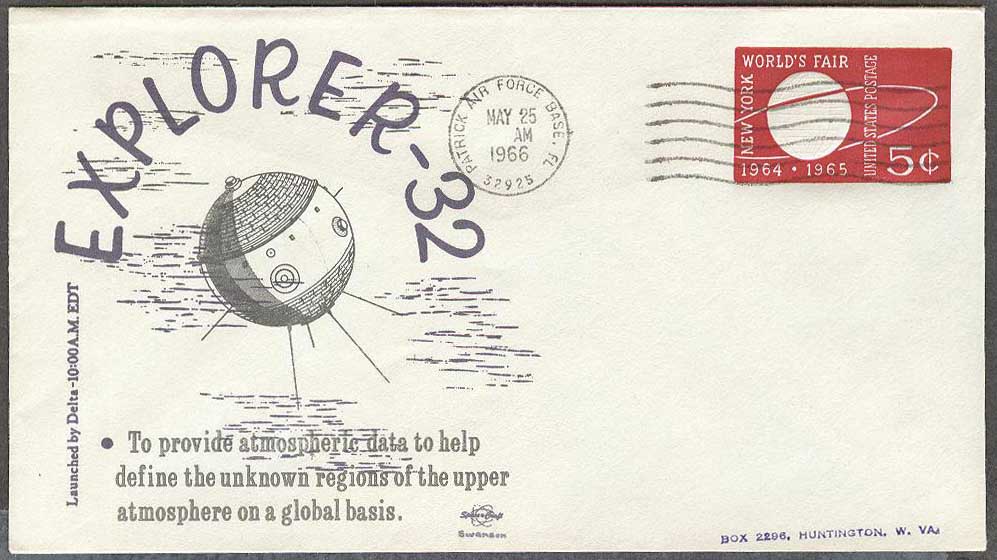

![[June 4, 1966] Over Under Sideways Down (Surveyor 1, Explorer 32, Kosmos 110 + 119!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660602surv2a-672x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1966] Worth Remembering (June 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660531cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1966] Things to Come and Things that Are(June 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660518cover-669x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1966] Rocky Jaunts (June 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 4, 1966] Pushing the Envelope (The State of Music: 1964-66)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660504mcguire-672x372.jpg)