by Gideon Marcus

[With Gemini 9 currently overhead and preempting regular network programming, it's easy to forget the other space spectaculars that are going on. Here's the skinny on four of the more exciting ones.]

Live from the Moon!

America may be second in the Moon race, but we sure aren't far behind the Soviets. Less than a month after the Russians managed their first soft-landing (with Luna 10, after several failed efforts), NASA's Surveyor 1 did it in just one try.

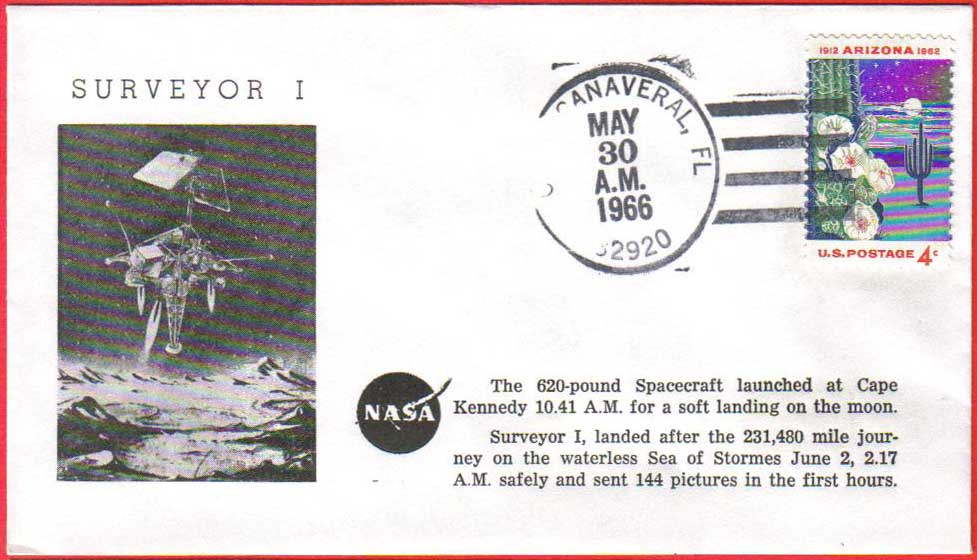

On May 30, 7:40 AM Pacific, Atlas-Centaur #8 lifted off from Cape Canaveral less than a second after its scheduled launch time. 757 seconds later, right on the button, Surveyor departed from its Centaur stage on an almost perfect path toward the Moon. Nevertheless, just before midnight, the spacecraft made a 20.75 second mid-course burn, reducing its landing margin of error from 250 miles to just 10.

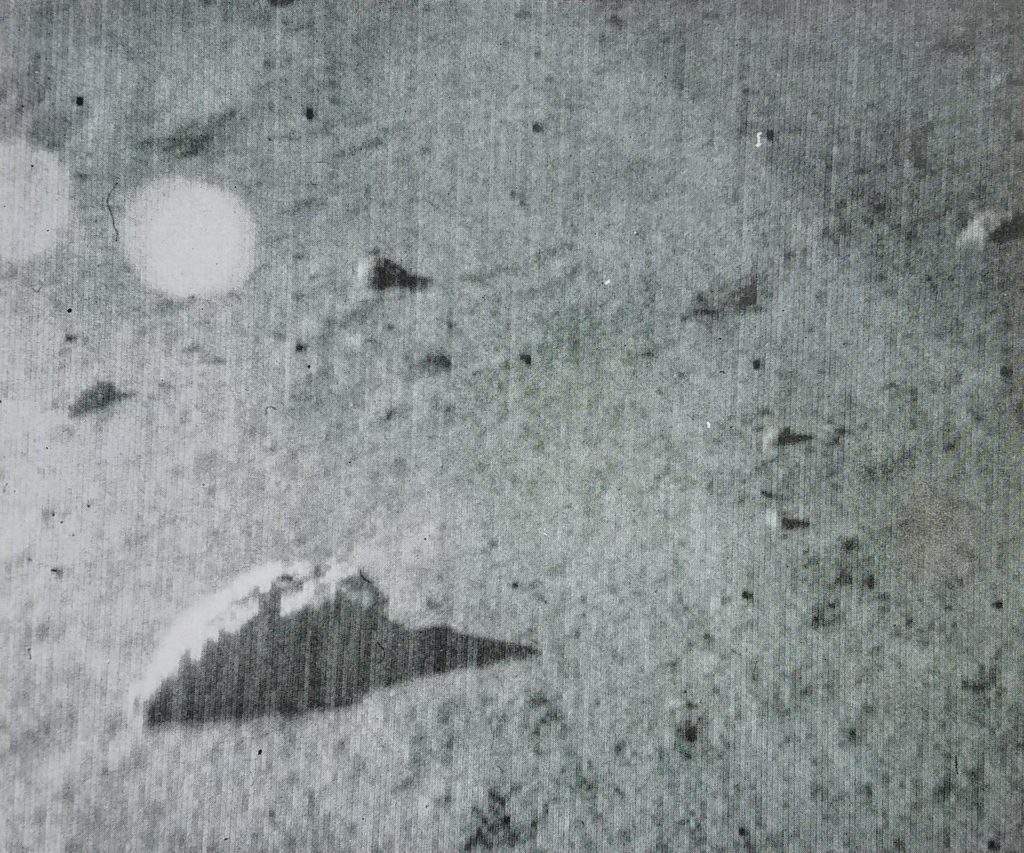

Surveyor made a flawless touchdown almost exactly two days later, at 11:17 PM on June 1. Shortly thereafter, America got its first pictures from the surface of the Moon.

The success of Surveyor marks several major achievements. Firstly, it's a success for the rocket that carried it. The Atlas-Centaur is the most advanced booster currently in existence, the first to utilize pure hydrogen for fuel and liquid oxygen for the oxidizer. There is no more efficient combination in existence, and the development of a system that could successfully utilize the pair has been tough. Now that the Centaur second stage is operational, it can be used on top of many different first stages — from Titan to Saturn. This dramatically increases the mass of the probes that can be sent to the Moon or to other planets. By comparison, Surveyor masses more than twice as much as the Ranger crash-lander probes, launched with the less powerful Atlas-Agena.

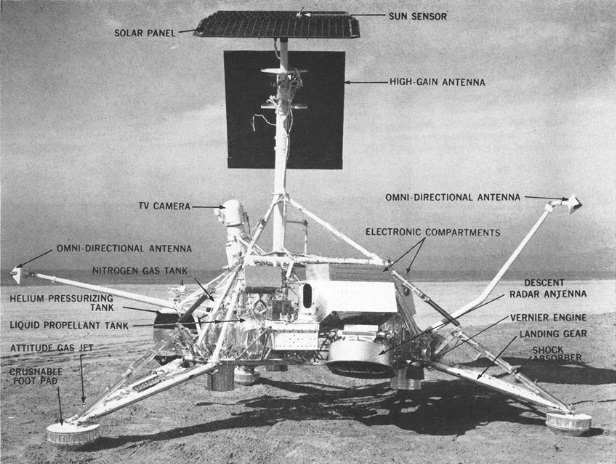

Surveyor's success also marks a big leap forward for the Project Apollo. It's been bandied about that this flight shaves a year off the schedule. This soft-lander mission was really a dress rehearsal for a manned spacecraft, and what a beautiful rehearsal. Reaching the lunar surface at just twelve feet per second, the three legged Surveyor with crushable aluminum honeycomb feet endured no undue strain. Moreover, it didn't sink into a quicksand of lunar dust, as had been previously feared. The landing spot, inside the dry Ocean of Storms, is in a zone that an Apollo mission will be sent to. If a probe can safely land, then a piloted Lunar Excursion Module can, too.

Finally, Surveyor 1 marks a triumph for lunar science. Not a huge one, mind you; Surveyor, like the latter Rangers, serves primarily as a handmaiden to the Apollo project. Nevertheless, we have our first hundred pictures, temperature data, seismological data, and radar reflectivity data of the lunar surface. The selenologists (lunar counterpart to Earth-based geologists) have plenty of information to play with.

Surveyor will continue broadcasting photos for at least the next 11 days, up through the lunar night. Then there will be several more missions in the series. You can be sure you'll read about them here!

Son of Explorer 17

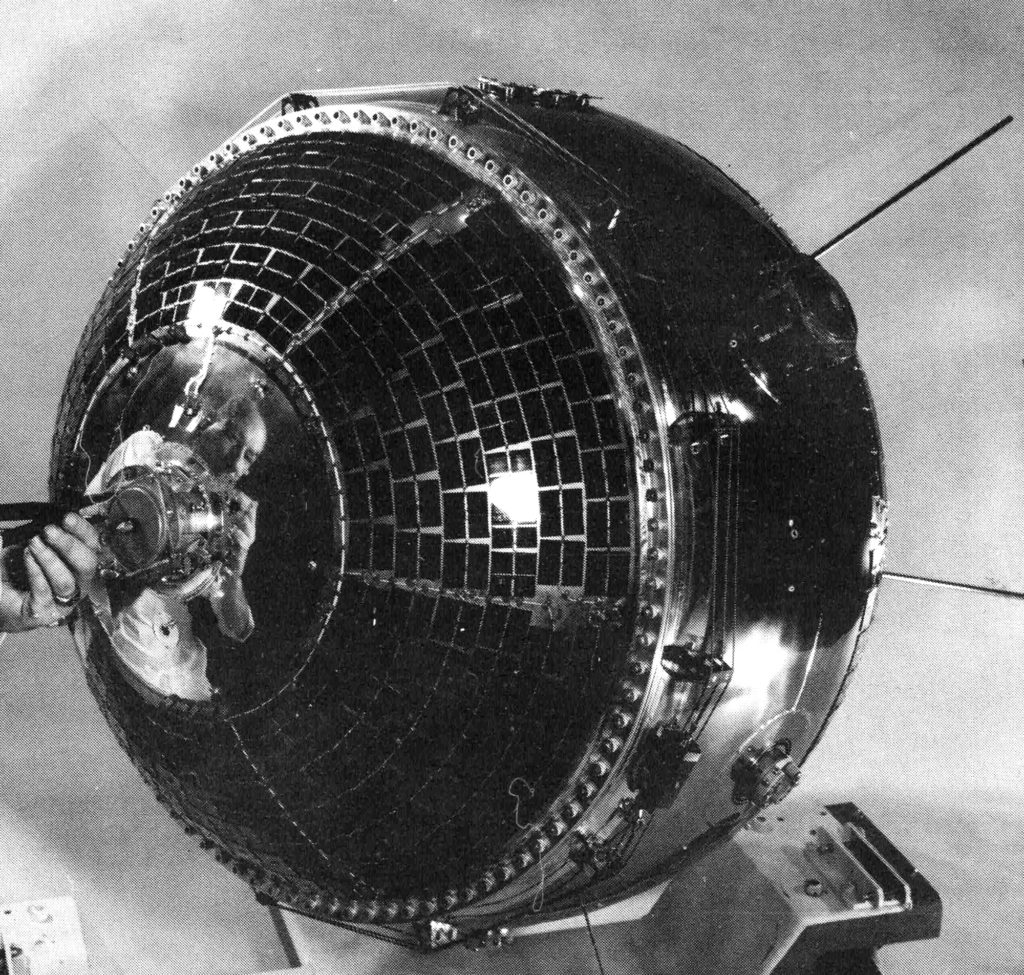

Three years ago, NASA sent up its first high orbit atmospheric satellite, Explorer 17. It only lasted a few months, going silent on July 10, 1963, but it returned a wealth of information on the least dense regions of our atmosphere.

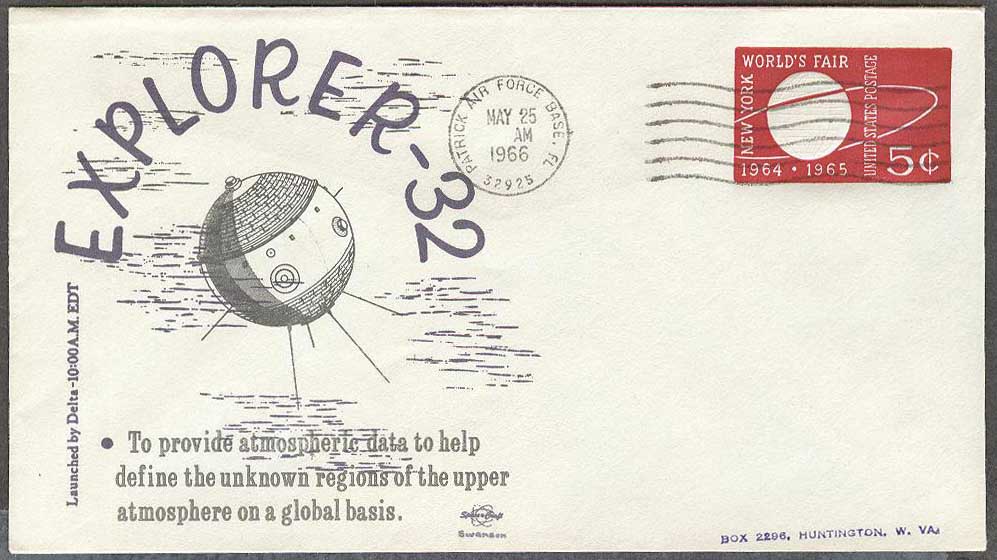

Every good story deserves a sequel. On May 25, 1966, we got one: Explorer 32, a satellite so similar to Explorer 17 that it must be considered kin, was hurled into an eccentric orbit that brings the ball of a probe zooming just 150 miles from Earth before flying far, far away.

Too far, actually. It was only supposed to reach ~500 miles from the Earth at apogee. Instead, because the Delta booster that carried Explorer didn't turn off in time, the satellite reaches 1000 miles in altitude before looping back.

This has not adversely affected plucky 32, and we are once again getting a wealth of data on the temperature, composition, density, and pressure of the upper atmosphere. Explorer 32 also has several improvements on its predecessor. Explorer 32 has solar cells, so its onboard batteries will last years instead of months. Because the satellite has a tape recorder on board, data can be stored rather than only relayed when a ground station is in sight. This means the data set from 32 will be continuous.

Even when the satellite goes silent, thanks to its perfectly round shape, it will be useful for measuring the density of the atmosphere, as 17 has been. A bunch of cameras are tracking 32 from the ground. Its slow orbital decay will tell us how thick the air is way up there.

It will be a legacy any parent could be proud of!

The Other Side

There have been a whole bunch of Kosmos satellites launched since our last update. While all of them are classified to some degree, and most of them (Kosmos 107, 109, 111, 113, 114, 115, and 117) were probably spy satellites akin to our biweekly Discoverer program, a couple stand out as unusual — mostly because we know what they are!

Kosmos 110, launched February 22, 1966, carried two caninauts: Veterok and Ugolyok. They and a menagerie of biological samples circled the Earth for an unprecedented 22 days before safely landing. We're not sure what capsule was used for the trip, but it was probably a modified Voskhod — I don't think they've had time to test a lunar spacecraft akin to our Apollo yet. Nevertheless, it's certain that this feat was conducted in support of long term efforts in space: either a Moon mission or a space station effort.

Most recently, Kosmos 119 went up on May 24. We can deduce its purpose based on what it's doing, namely emitting 31.8 kHz and 44.9 kHz radio-waves. It is believed that 119 is an ionospheric experiment to determine if and how ultralow frequency electromagnetic waves pass through that region of the atmosphere. Data from this satellite will be useful for estimating charged-particle concentration in the lower ionosphere. Whether the satellite's mission is purely scientific or serves to support some sort of military application is unknown. Nevertheless, it's nifty!

Things to Come

Of course, the big news over the next week will be how successful Gemini 9 is at completing its rendezvous, docking, and spacewalk maneuvers. You can be certain we'll have full coverage of that mission after splashdown next week!

Speaking of adventure in space, don't miss your chance to get this amazing novel by yours truly!

From a recent review:

Imagine Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys … in space! Kitra took me back to my childhood when I would have loved to read stories of young people in sci-fi settings overcoming difficult odds and conquering the universe. In Marcus's own words: "Tales of friendship, ingenuity, and wonder."

Take a group of diverse friends (not all human), toss in a bit of gender fluidity, cultural diversity, and conflict, and push them to their limits as they have to work together to overcome an unexpected threat. This YA fiction will thrill any number of budding science fiction fans.

![[June 4, 1966] Over Under Sideways Down (Surveyor 1, Explorer 32, Kosmos 110 + 119!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660602surv2a-672x372.jpg)