Tune in tonight at 7pm Pacific for the latest episode of Science Fiction Theater!

by Cora Buhlert

This is not the article I was planning to write this month. In fact, I was going to review the Ballantine Adult Fantasy collection Zotique, which reprints the haunting stories Clark Ashton Smith published in Weird Tales for the first time in more than thirty years.

However, Clark Ashton Smith will have to wait – he has been waiting for more than thirty years by now, after all – because there have been some most shocking developments in the West German leftwing sphere.

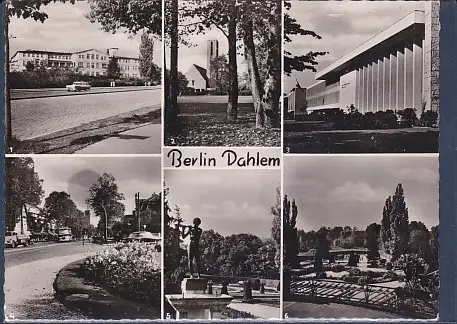

A Pleasant Spring Day in West Berlin

The Dahlem neighbourhood of West Berlin is a normally a quiet upper middle class suburb, where nineteenth and early twentieth mansions line leafy cobblestoned streets. There is little traffic here, birdsong can be heard echoing from the gardens and rarely are there sounds louder than a whirring of a lawnmower or the barking of a dog. But on May 14 at eleven AM, the quiet of Dahlem was interrupted by the sound of gunfire.

The source of those shots was a white mansion with dark green shutters, nestled in a garden with birch and pine trees on Miquelstraße. It was a warm and sunny spring day, so the windows on the ground floor were wide open. This mansion houses the library of the German Central Institute for Social Issues, i.e. not a place where anybody would expect gunfire.

Shortly after the shots, an engine howled and a car raced down the street. Georg Linke, the 62-year-old janitor of the Institute, staggered across Miquelstraße, clutching his side, only to collapse in a driveway, bleeding profusely from gunshot wounds in his arm and his abdomen. He was found by a student who wanted to consult the library.

"That was the Meinhof woman," a man in uniform yelled from the open window of the Institute, while the student yelled back they should call an ambulance, because someone had been shot.

Initially, there was some confusion about what precisely had happened at the German Central Institute for Social Issues. But gradually, it became clear that the quiet Miquelstraße had just witnessed one of the boldest prison breaks in recent German history.

Continue reading [July 10, 1970] Prison Break in West Berlin: The Liberation of Andreas Baader

![[July 10, 1970] Prison Break in West Berlin: The Liberation of Andreas Baader](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/55979364-jpg-100-1920x1080-1-672x372.jpg)

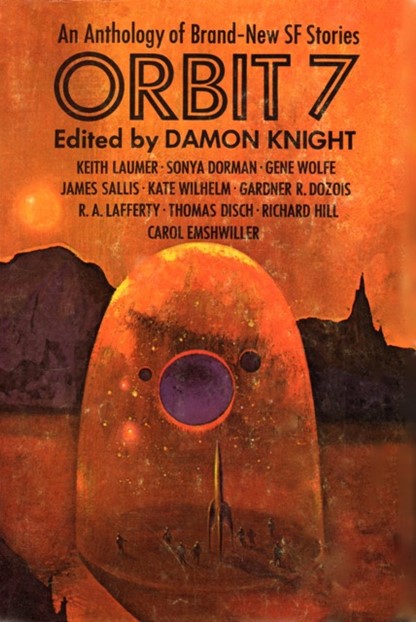

![[July 8, 1970] I'm Still Marching Some More (<i>Orbit 7</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Orbit-C-416x372.jpg)

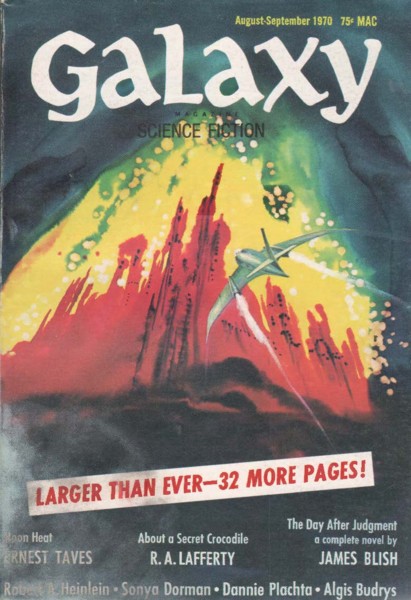

![[July 6, 1970] The Day After Judgment (August/September 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700708galaxycover-411x372.jpg)

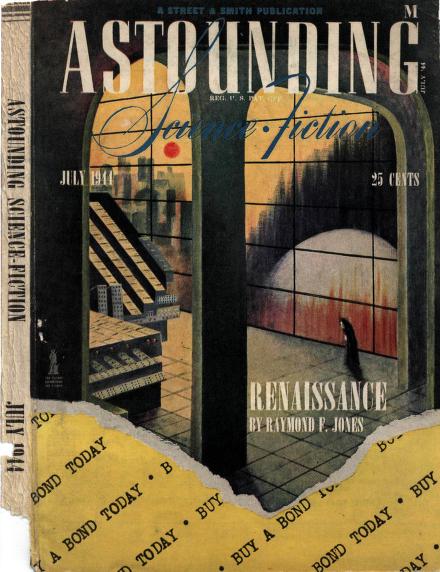

![[July 4, 1970] Coming Attractions (<em>The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One</em>, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Astounding_v33n05_1944-07_AK_0000-440x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Venture-1970-08-Cover-486x372.jpg)

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1970] Welcome to Blood Island (Four Filipino Fright Films)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700628movies-672x372.jpg)

![[June 27, 1970] Deeper than Amber, more mindless than a Worm… (June Galactoscope: The Third)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700627covers-672x372.jpg)

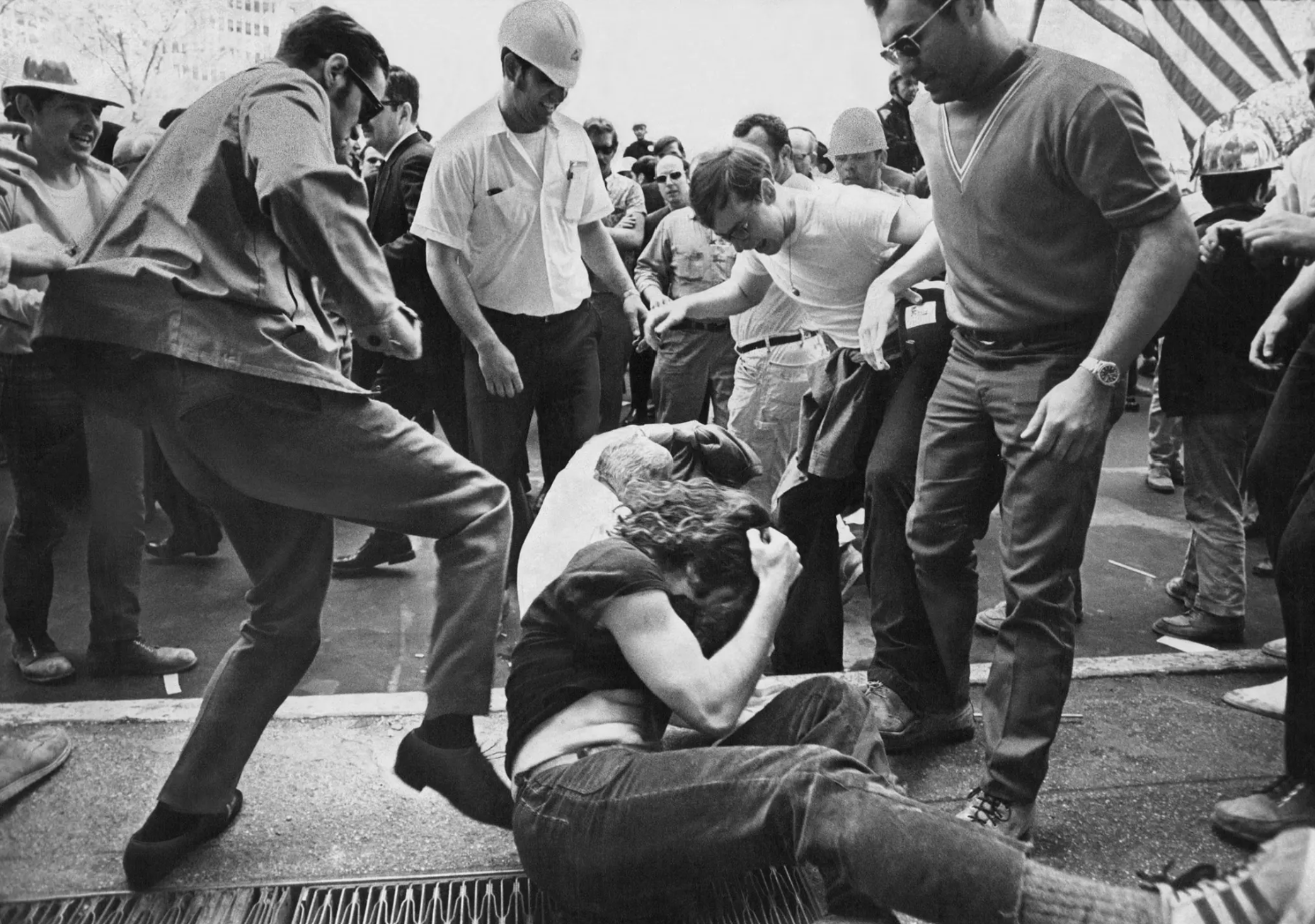

![[June 26, 1970] Hard Hats & Flower Power Collide](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-18-230824-672x372.png)

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)