[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

by Kaye Dee

Recently, The Traveller covered the launch of the TIROS-M weather satellite, noting that the rocket’s payload also included a small Australian-made ham radio satellite, OSCAR-5 (Orbiting Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio), also known as OSCAR-A.

Cover of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre's in-house magazine, marking the launch of ITOS-1/TIROS-M and Australis-OSCAR-5

Cover of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre's in-house magazine, marking the launch of ITOS-1/TIROS-M and Australis-OSCAR-5

A New Star in the Southern Cross

It was exciting to be in “Mission Control” at the University of Melbourne when the satellite was launched in the evening (Australian time) on 23 January. You should have heard the cheers! After all, Australis-OSCAR-5 (AO-5), as we call it, is Australia’s second satellite. It’s also the first amateur radio satellite built outside the United States and the first OSCAR satellite constructed by university students – in this case, members of the Melbourne University Astronautical Society (MUAS).

The MUAS student team with the engineering model of Australia's first amateur radio satellite

The MUAS student team with the engineering model of Australia's first amateur radio satellite

Radio Hams and Satellite Trackers

Commencing in 1961, the first OSCAR satellite was constructed by a group of American amateur radio enthusiasts. Cross-over membership between MUAS and the Melbourne University Radio Club (MURC) encouraged the students to begin tracking OSCAR satellites, moving quickly on to tracking and receiving signals from many other US and Soviet satellites.

Nimbus satellite image of the western half of Australia received by MUAS for the weather bureau

Nimbus satellite image of the western half of Australia received by MUAS for the weather bureau

One of MUAS’ achievements was the first regular reception in Australia of images from TIROS and Nimbus meteorological satellites. By 1964, they were supplying satellite weather images daily to the Bureau of Meteorology, before it established its own receiving facilities.

"How Do We Build a Satellite?"

After tracking OSCARs 3 and 4 in 1965, the MUAS students decided to try building their own satellite. “No one told us it couldn’t be done, and we were too naive to realise how complex it would be to get the satellite launched!”, an AO-5 team member told me at the launch party. MUAS decided to build a small ‘beacon’ satellite which would transmit telemetry data back to Earth on fixed frequencies.

Even before Australia’s first-launched satellite, WRESAT-1, was on the drawing board, the Australis satellite project commenced in March 1966. Volunteers from MUAS, MURC and university staff worked together to design and build the satellite, with technical and financial assistance from the Wireless Institute of Australia and a tiny budget of $600. The Australian NASA representative also gave the project invaluable support. The students acquired electronic and other components through donations from suppliers where possible: the springs used to push the satellite away from the launcher were generously made by a mattress manufacturer in Melbourne. Any other expenses came out of their own pockets!

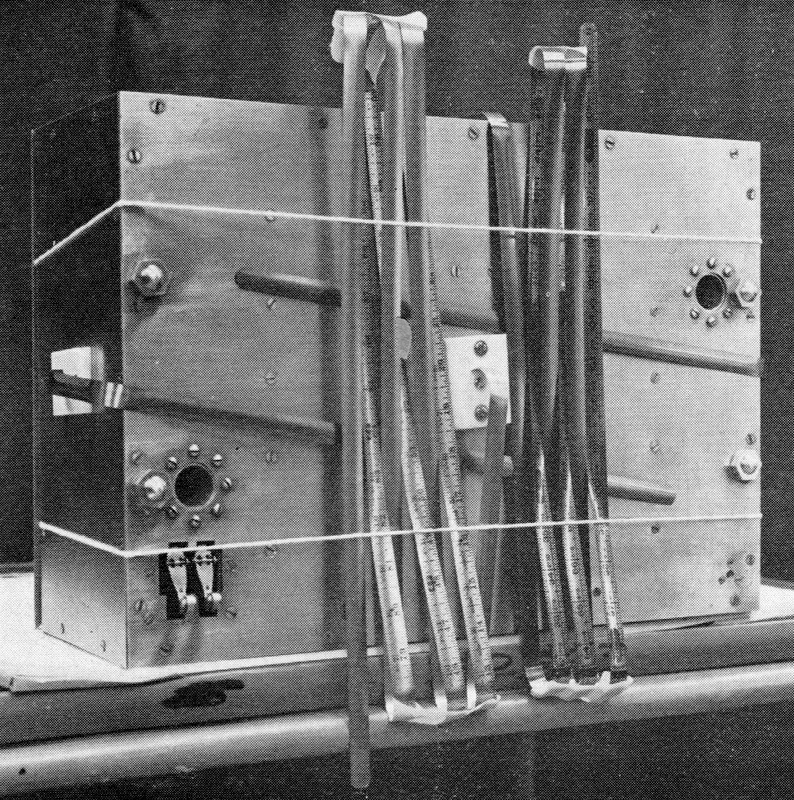

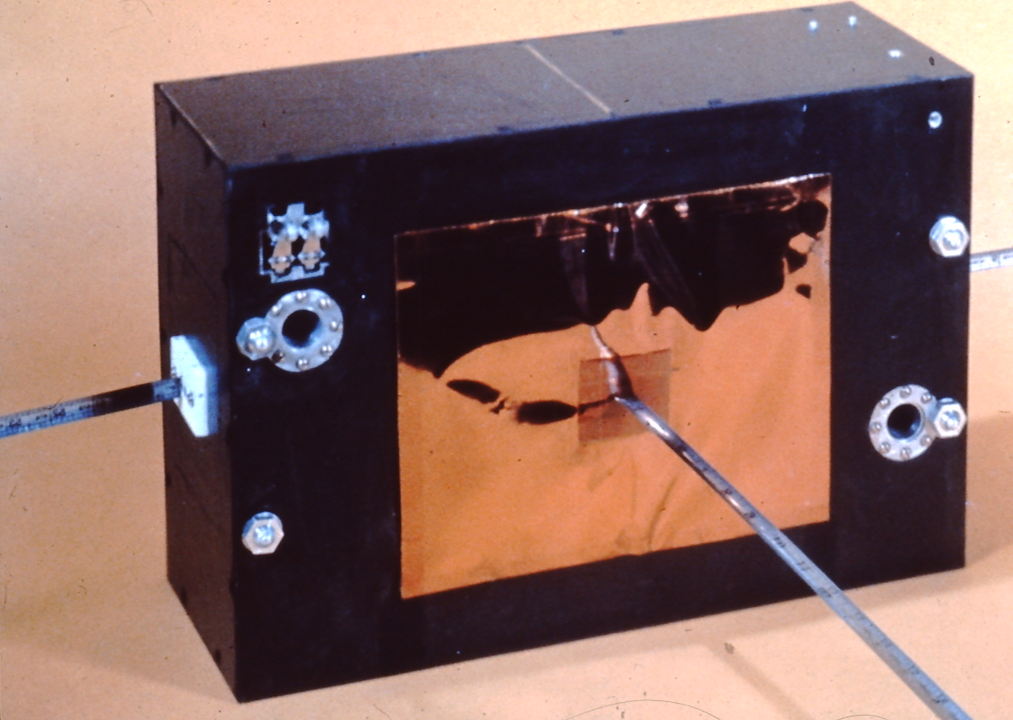

Carpenter's steel tape was used to make AO-5's flexible antennae, seen here folded in launch configuration. Notice the inch markings on the tape!

Carpenter's steel tape was used to make AO-5's flexible antennae, seen here folded in launch configuration. Notice the inch markings on the tape!

AO-5 is a fantastic example of Aussie ‘make-do’ ingenuity. A flexible steel measuring tape from a hardware shop was cut up to make the antennae. The oven at the share house of one team member served to test the satellite’s heat tolerance, and a freezer in the university's glaciology lab was unofficially used for the cold soak. Copper circuit boards were etched with a technique using nail varnish, and a rifle-sight was used to help tune the antennae! Various components, including the transmitters and command system, were flight-tested on the university’s high altitude research balloon flights.

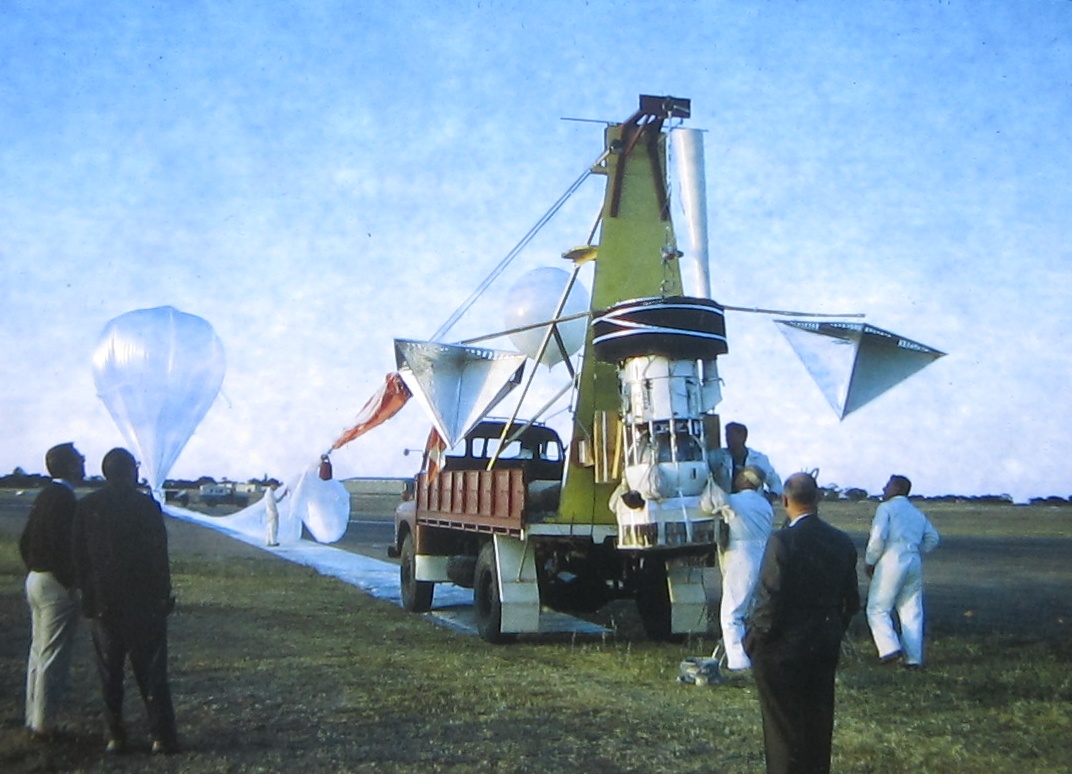

A university lab freezer and hitching a ride with university experiments on US HiBal high altitude balloon flights in Australia used to test the ruggedness of AO-5 components

A Long Wait for Launch

Australis was completed and delivered to Project OSCAR headquarters in June 1967, well before WRESAT’s launch in November that year. Unfortunately, AO-5 then had to wait a few years for a launch to be arranged by the Amateur Radio Satellite Corporation (AMSAT), which now operates the OSCAR project. However, it is surely appropriate that, as OSCAR-5, it finally made it into orbit with a weather satellite.

After launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base, AO-5 was placed into a 115-minute orbit, varying in altitude between 880 – 910 miles. This means it will be in orbit for hundreds of years – unlike the short-lived WRESAT.

In Orbit at Last!

Battery-powered, Australis-OSCAR-5 weighs only 39 pounds and carries two transmitters, beaming out the same telemetry signal on the two-metre and 10-metre amateur radio bands. Its telemetry system is sophisticated but designed for simple decoding without expensive equipment. The start of a telemetry sequence is indicated by the letters HI in Morse code, followed by data on battery voltage, current, and the temperature of the satellite at two points as well as information on the satellite's orientation in space from three horizon sensors.

AO-5 includes the first use in an amateur satellite of innovations such as a passive magnetic attitude stabilisation system (which helps reduce signal fading), and a command system to switch it on and off to conserve power. Observations are recorded on special standardised reporting forms that are suitable for computer analysis.

Just 66 minutes after launch, the first signal was detected in Madagascar and soon other hams reported receiving both the two and 10-metre signals on the satellite's first orbit. At “Mission Control” in Melbourne, we were thrilled when MURC members managed to pick up the satellite’s signals! By the end of Australis’ first day of operation, AMSAT headquarters had already received more than 100 tracking, telemetry and reception reports.

A selection of local newspaper cuttings following AO-5's launch. There was plenty of interest here in Australia.

A selection of local newspaper cuttings following AO-5's launch. There was plenty of interest here in Australia.

The two-metre signal failed on 14 February, but the 10-metre transmission continues for now. How much longer AO-5’s batteries will last is anybody’s guess, but the satellite has proven itself to be a successful demonstration of the MUAS students’ technical capabilities, and the team is already contemplating a more advanced follow-on satellite project.

This philatelic cover for the ITOS-1/TIROS-M launch, includes mention of AO-5, but the satellite depicted is actually OSCAR-1

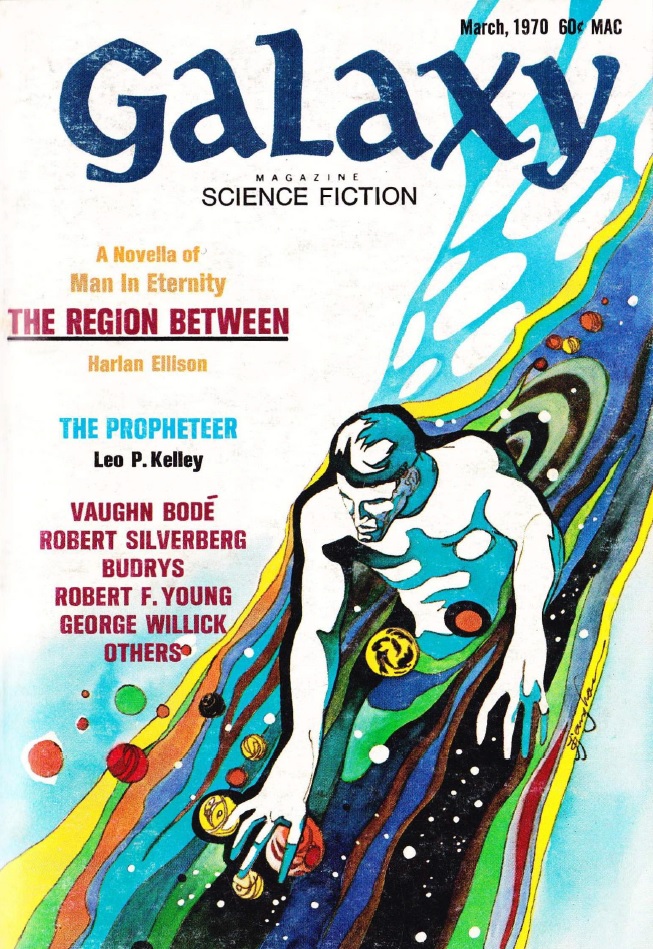

by Gideon Marcus

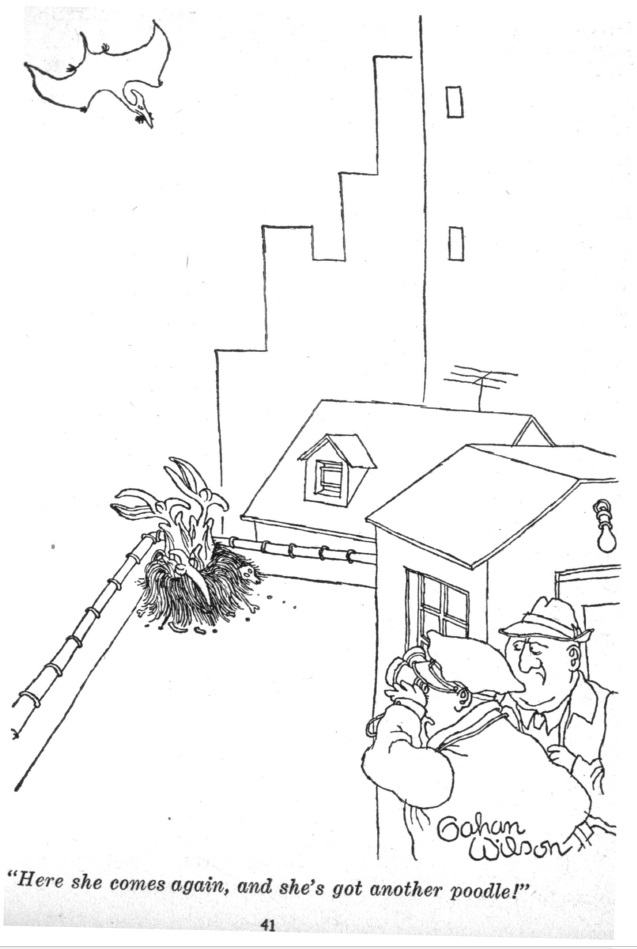

Fantastic emanations on Earth

And now that you've had a chance to digest the latest space news, here's some less exciting (but no less necessary) coverage of the latest issue of F&SF.

by Ronald Walotsky

![[February 20, 1970] Fun-nee enough… (<i>OSCAR 5</i> and the March 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700220coverfsf-631x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1970] Boldly going to the Region Between (March 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700208galaxycover-653x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1968] Giants among Men (November 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681020cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 13, 1964] Save us from Yourselves (January 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641213cover-480x372.jpg)

![[April 22, 1964] World Affairs (May 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640422cover-601x372.jpg)