by Victoria Silverwolf

A trio of new works, two of them inside the same book, take readers from the far reaches of the galaxy to the depths of the ocean. (Sounds like last month's Galactoscope, doesn't it?) Let's start with the latest Ace Double, containing two short novels (or long novellas) set in interstellar space.

Gedankenexperiment

Cover art by Peter Michael.

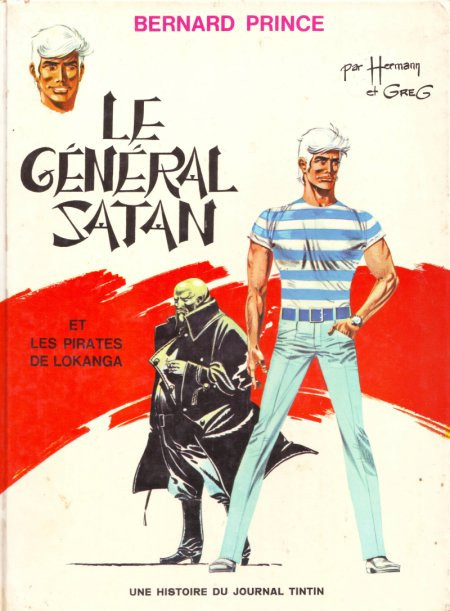

The Rival Rigelians, by Mack Reynolds

This is an expansion of the novella Adaptation, which appeared in the August 1960 issue of Astounding/Analog. (That's during the brief period when both titles appeared on the cover of the magazine. Confusing, isn't it?)

Cover art by John Schoenherr.

The Noble Editor thought it was so-so at the time. Let's see if it's any better, like fine wine, after seven years.

Cold War Two

Long before the story begins, Earth colonized a large number of planets with about one hundred people per world. Over several generations, the colonies degenerated from scientifically advanced to primitive, due to the lack of support from the home world. Then each slowly made their way back up to a particular level of technological sophistication.

(If this sounds like a really lousy way to populate the galaxy, I agree. The author is clearly more interested in setting up a thought experiment than in ensuring plausibility.)

It seems that two inhabited worlds orbit the star Rigel. One is similar to Italy during the time of feudalism. The people on the other are similar to the Aztecs.

Rigel is part of the constellation Orion; one of his feet, to be exact.

Earth sends a team of folks to Rigel to bring the colonies up to a modern level of technology. They argue a bit about what to do, then finally agree to split up. One group will bring the free market to the feudalists, and the other will impose a state-controlled economy on the Aztecs. It's capitalism versus communism all over again! Long story short, things don't work out very well for either bunch.

The main difference between the original novella and this expanded version is the addition of two female members to the visiting Earthlings. Both are physicians. Unfortunately, they are pure stereotypes.

One is the Good Girl, doing the best she can to help the colonists while remaining loyal to the man she loves. (To add a little romantic tension to the plot, the author has him choose to go to the Aztec planet while she opts to work on the Italian planet.)

The other is the Bad Girl, teasing the men by exchanging the standard uniform for a sexy gown before they even reach Rigel. On the Aztec planet, she sets herself up as the mistress of whichever fellow happens to be in power at the time, and rules over the locals like a wicked queen.

The author's point seems to be that both pure capitalism and pure communism are seriously flawed. I've seen this theme come up in his work before, most recently in his spy yarn The Throwaway Age in the final issue of Worlds of Tomorrow.

This story isn't quite as blatant a fictionalized essay as that one was, but it comes close. Besides the two-dimensional female characters, we have male characters that are mostly either fools or scoundrels. It's readable, certainly, and you may appreciate its satiric look at humanity's attempts to create workable socioeconomic systems.

Three stars.

Naval Maneuvers

Born in England but living in Australia since 1956, A. Bertram Chandler has been working on merchant ships since 1928. It's no wonder, then, that the space-going vessels in his stories often seem like sailing ships. One can almost smell the salt air and hear the wind rippling in the sails.

Many of his semi-nautical tales feature the character of John Grimes, sort of a Horatio Hornblower of the galaxy. My esteemed colleague David Levinson recently reviewed a pair of these yarns that appeared in If. Why do I bring this up? You'll see.

Cover art by Kelly Freas.

Nebula Alert, by A. Bertram Chandler

This latest work once again makes space seem like the ocean, and those who journey through it like seadogs. (It also serves as a nice bridge between Reynold's interstellar allegory and the sea story I'll discuss later.)

All Hands On Deck!

The starship Wanderer is under the command of a husband-and-wife team. She's the owner and he's the captain. Among the crew are another married couple and a couple of bachelors. They accept the challenge of transporting several Iralians back to their home world.

Iralians are very human-like aliens. So similar to people, in fact, that romance blooms between one of the bachelors and one of the passengers. (They're both telepaths, which must help.) There are some important differences, however.

The Iralians have a very short gestation period, and multiply rapidly. Their offspring inherit the learned skills of their parents, in a kind of mental Lamarckism. Unfortunately, the combination of these traits makes them valuable slaves; the owners have a steady supply of fully trained workers.

During the voyage, a trio of pirate ships threatens the Wanderer. (The identity of the would-be slavers on these vessels is an interesting plot twist, which I won't reveal here.) In order to evade the attackers, our heroes take the very dangerous gamble of entering the Horsehead Nebula.

The real Horsehead Nebula, which is aptly named.

It seems that no starship has ever returned from the nebula, and there are indications that it does something weird to time and space. In fact, the Wanderer enters a parallel universe, where they encounter a ship under the command of none other than John Grimes! Suffice to say that the meeting leads to a way to exit the nebula safely and defeat the pirates.

Unlike Reynolds, Chandler doesn't seem to have any particular axe to grind. This is strictly an adventure story, meant to entertain the reader for a couple of hours. It succeeds at that modest goal reasonably well. It's not the most plausible story ever written, and you won't find anything profound in it, but it's not a waste of time.

Three stars.

The Patron Saint of Science Fiction

Margaret St. Clair (no relation to actress Jill St. John, who recently appeared in the big budget flop The Oscar, co-written by none other than Harlan Ellison) has been publishing fiction since the late 1940's. Much of her short fiction is strikingly original, with a haunting, dream-like mood. (I particularly like her stories for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which appear under the pseudonym Idris Seabright.)

She's offered readers a few short novels as halves of Ace Doubles, as well as the full-length novel Sign of the Labrys. Both the Noble Editor and I agreed that this was a unique, very interesting mixture of apocalyptic science fiction and mysticism, if not fully satisfying. The book featured quite a lot of lore from the neo-pagan religion Wicca, and I understand that St. Clair was initiated into that faith last year.

Cover art by Paul Lehr.

The Dolphins of Altair, by Margaret St. Clair

Dolphins have appeared in science fiction for a while now, from Clarke's 1963 work mentioned below to this year's French novel Un animal doué raison by Robert Merle. Some of this seems to be inspired by recent attempts to communicate with dolphins by the controversial researcher John C. Lilly. Or maybe they've just been watching reruns of Flipper, which was cancelled last month. In any case, let's see how this new book handles the theme.

People of the Sea

(Apologies to Arthur C. Clarke for stealing the title of his Worlds of Tomorrow serial, now available in book form as Dolphin Island. I hope he's too busy scuba diving off the coast of Ceylon to notice.)

Appropriately, the novel is narrated by a dolphin. He relates how three human beings came to the aid of his kind.

The first is Madelaine. She is particularly sensitive to telepathic messages sent by the dolphins. So much so, in fact, that she suffers from amnesia when they call her. Nonetheless, she answers their distress signal by journeying to a small, rocky, uninhabited island off the coast of Northern California.

Next is Swen. The dolphins don't directly contact him, the way they do Madelaine, but he overhears the message and shows up at the same place.

Last is Doctor Lawrence. He becomes involved with Madelaine when he treats her amnesia. Although he has no ability at all to receive psychic messages from the dolphins, he follows her to the island.

The dolphins, some of whom have learned to speak English, are fed up with the way that human beings pollute their sea and keep their kind captive. They seek help from the unlikely trio.

At first, this involves rescuing several dolphins from a military facility. The plan is to use a powerful explosive device (which Swen has to steal) to trigger an earthquake that will break open the seawall that keeps them in captivity. Although the three agree to take this action, which will inevitably cause great destruction and is likely to cost human lives, they try to minimize the harm done to their own kind by timing the quake when the fewest number of people will be around.

If this all seems to strain your willingness to suspend your belief, wait until you see what we find out next.

It seems that both dolphins and humans are the descendants of beings who came from a planet orbiting the star Altair (hence the title.) They showed up on Earth about one million years ago. Some chose to remain on land, others went to the ocean. Over many thousands of years, they diverged into the two species.

Altair, located near a very appropriate constellation.

The dolphins remember the covenant made so long ago, that the two groups would remain on friendly terms. Betrayed by the forgetful humans, they are ready to use any means possible to end the abuse of their kind. The next step is to use ancient technology from Altair to melt the ice caps. As you might imagine, this leads to an apocalyptic conclusion.

Unsurprisingly, given the author, this is an unusual book. It combines a science fiction thriller with a great deal of mysticism. The author is obviously incensed by the way people enslave dolphins and dump poison into the ocean. The reader is definitely supposed to root for the dolphins in their war against humanity.

The three human characters are quite different from each other. Swen is probably the most normal, and serves as the novel's action/adventure hero, at least to some extent. Madelaine is an ethereal creature, almost like some kind of mythic being. Doctor Lawrence is an enigma. He informs the military about the dolphins, leading to an attack on the island, but he is also a misanthrope, the most eager to wreak destruction on humanity.

Like Sign of the Labrys, The Dolphins of Altair is a fascinating novel with disparate elements that don't always quite mesh, and an odd combination of science fiction themes with the purely mystical. I can definitely say that I'm glad I read it, and that it is likely to stay in my memory for some time to come.

Four stars.

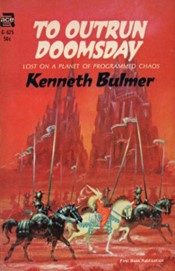

To Outrun Doomsday, by Kenneth Bulmer

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Bulmer is very much a mixed author for me. He has produced great works, like The Contraption or City Under the Sea. But also, less interesting pieces, such as Behold the Stars or his Terran Space Navy series.

Which Bulmer do we get in To Outrun Doomsday? Luckily for me, it is definitely the former, as I think this is his best work to date.

Balance of Imagination

I think it is worth quickly addressing the issue some readers have with Bulmer’s work. Much of his writing hew very close to real world scenarios, such as war novels. For some people this presents the same issue I have seen discussed in the recent Star Trek episode Balance of Terror.

They ask, “if you have the limitless possibilities of science fiction, why would you do submarine warfare in space?” I say, “if you have the limitless possibilities of science fiction, why wouldn’t you do submarine warfare in space!”

As such, it is with the scenario To Outrun Doomsday. Jack Waley is a gadabout on a starship which seems to be acting as a cruise liner. He sees himself as a kind of old-fashioned rake, seducing women and generally pleasure seeking across the galaxy.

This life falls apart when an accident befalls the ship he is on and his lifeboat crashes on a planet that has, apparently, never encountered people from Earth. There he lives with the tribe of “The Homeless Ones” learning their ways whilst also facing the hostile “The Whispering Wizards”.

This all seems like it could be an old-fashioned castaway story in a boy’s adventure magazine from the 30s, and I am sure his critics will say as such. But there are a number of elements that raise it up.

To Outrun Cliches

Firstly, when Bulmer’s writing is good, it is so good it fully takes me away into his world in a way I am in awe of. For example:

The ship blew.

How then describe the opening to nothingness of the warmth and light and air of human habitation?

From the fetus of womblike comfort to space-savaged death-the ship blew. Metal shivered and sundered. Air frothed and vanished. Heat dissipated and was cold. Light struggled weakly and was lost in the multiplicity of the stellar spectra. The ship blew.

Here and there in the mightily-puny bulk, pockets of air and light and warmth yet remained for a heartbeat, for the torturing time to scream in the face of death. Some, a pitiful few persisted for a longer time.

But then is also at other times willing to bring in silliness when the scene requires it:

“I’m sorry that-“ Waley began.

A hand shook. “Quiet!”

Waley stopped being sorry that.

These are merely a couple of examples. Bulmer uses a full literary toolbox to make an exciting and engaging adventure.

Then you have Waley’s character. He is the kind of fellow you expect to hang around in bars until the wee small hours and take Playboy articles as his guide to life. But as we are not meant to see this as something to admire, he is at different times referred to as “a walking lecherous horrid heap of contagion” and ends getting chained up as a galley slave for following his licentious urges. Throughout we follow the journey of him learning there are more valuable things in life than carnal pleasures and forging real friendships with people.

At the same time this is balanced by the abundance of different women throughout the story. Their journeys are independent of Waley’s adventures and often are quite dismissive of him. They are simply well-rounded inhabitants of the world.

Further, this surface story is slowly revealed to be covering up something deeper. There are intriguing breadcrumbs laid out for you. For example, Waley never sees any children, buildings collapse and no one takes any notice, and, strangest of all, praying for any item (assuming it is not or has not been living) results in it appearing instantly. I will not reveal the mystery, but it adds strangeness to what could be a middling space fantasy tale like Norton’s Witch World saga.

The story is not without flaws. Whilst the emotional conclusion is very strong, tying up the main plot mystery made me put my head into my hands at how silly it is (if also reminding me how important it is I get it to the weeding).

It also occasionally goes into racist language when describing enemies. For example:

Small wiry yellow men with spindly legs and bulbous bodies, with Aztec lips and grinning idiot faces

These are very rare occurrences and not a core part of the story, but still wish they had been excised.

I also wished that the book was longer. Whilst I noted there were a number of interesting characters, particularly among the women, we do not have as much time with them as I would have liked. If it could have been allowed another 40 or so pages, it would just have allowed the extra space needed to flesh them out.

But I am happy to give it a very high four stars.

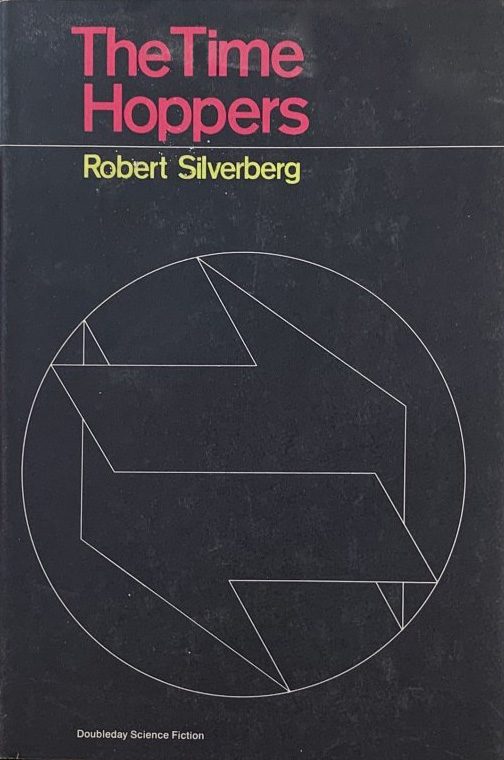

by Gideon Marcus

The Time Hoppers

The jacket for Silverbob's latest novel notes that he "and his wife live in Riverdale, New York, in a large house also occupied by a family of cats (currently four permanent ones), a fluctuating number of kittens, and thousands of books, some of which he has not written." This only slightly overstates the prodigiousness with which Mr. Silverberg cranks out the prose. Sometimes, Bob gives it his all and turns out something rather profound like his recent Blue Fire series, which was serialized in Galaxy and came out in book form this month as To Open the Sky.

Other times, we get books like The Time Hoppers, clearly produced in a pressured week, perhaps between passion projects. The short novel takes place in the 25th Century, but this is no Buck Rogers future. Rather, we have an overpopulated dystopia where almost everyone is on the dole, society is calcified into numbered levels of privilege, and most live in enormous buildings that soar into the sky as well as plunge deep in the ground. Within this crowded world, we follow the viewpoint of Quellen, a Level Seven local police boss, hot on the trail of the time hoppers. These are folks who are leaving the future for the spaciousness of the past. They know these temporal refugees exist because they are already recorded in the history books. Can Quellen stop them before the trickle becomes a flood? Should he?

There are a lot of problems with this book. Quellen is a fairly unlikeable person, a sort of Winston Smith-type at the outer levels of the party, enjoying a few illicit pleasures like a second home in Africa (conveniently depopulated by a century-old plague). Society in the future makes no sense–it seems an extrapolation of a 1950s view of American society, where the men work and the women are shrieking housewives or grasping adventuresses. Never mind that, in a world where everyone is unemployed, why there should be a sharp dichotomy between male and female roles goes unexplained. Just "Chicks, am I right, folks?"

There a sort of shallowness to the book, and the time travel bit is almost incidental. Particularly since, as the hoppers have already been recorded in the past, any efforts to stop them in the future must inevitably be thwarted. Also, the idea that these hoppers wouldn't be of prime concern to the powers-that-be (or in the case of this book, actually just one power-that-is) far earlier than four years into the hopping seems ludicrous.

But, I have a perverse penchant for books with the word "Time" in the title, however misleading, as well as stories that have explicit social ranks for people. And Silverberg, even on a bad day, has a minimum threshold of competence.

So, three stars.

And that's that! While you're waiting for the next Galactoscope, come join us in Portal 55 to chat about these and other great titles:

![[May 28, 1967] Around the World in 80 Months (May 1967 Space Roundup)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670528earth-672x372.jpg)

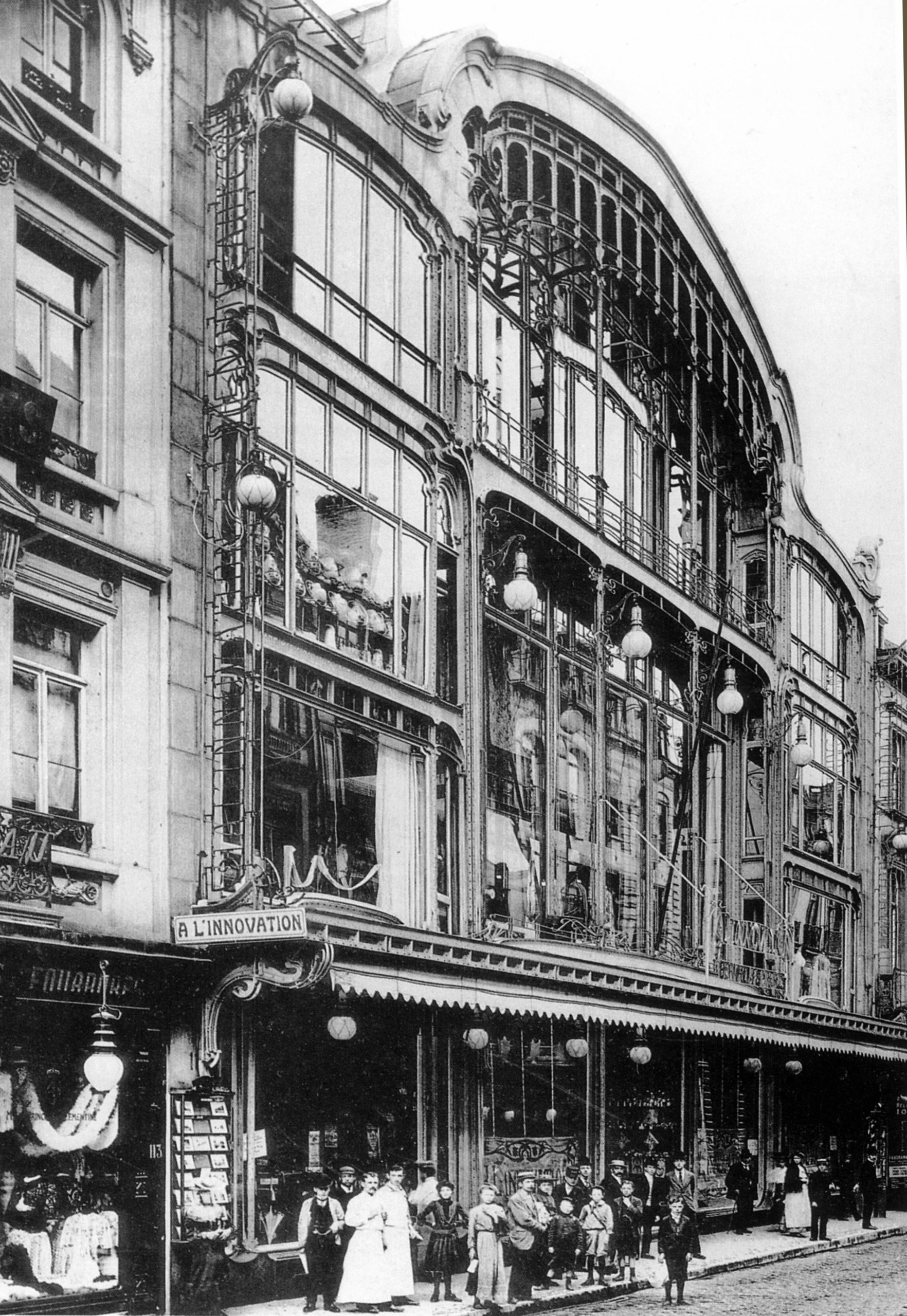

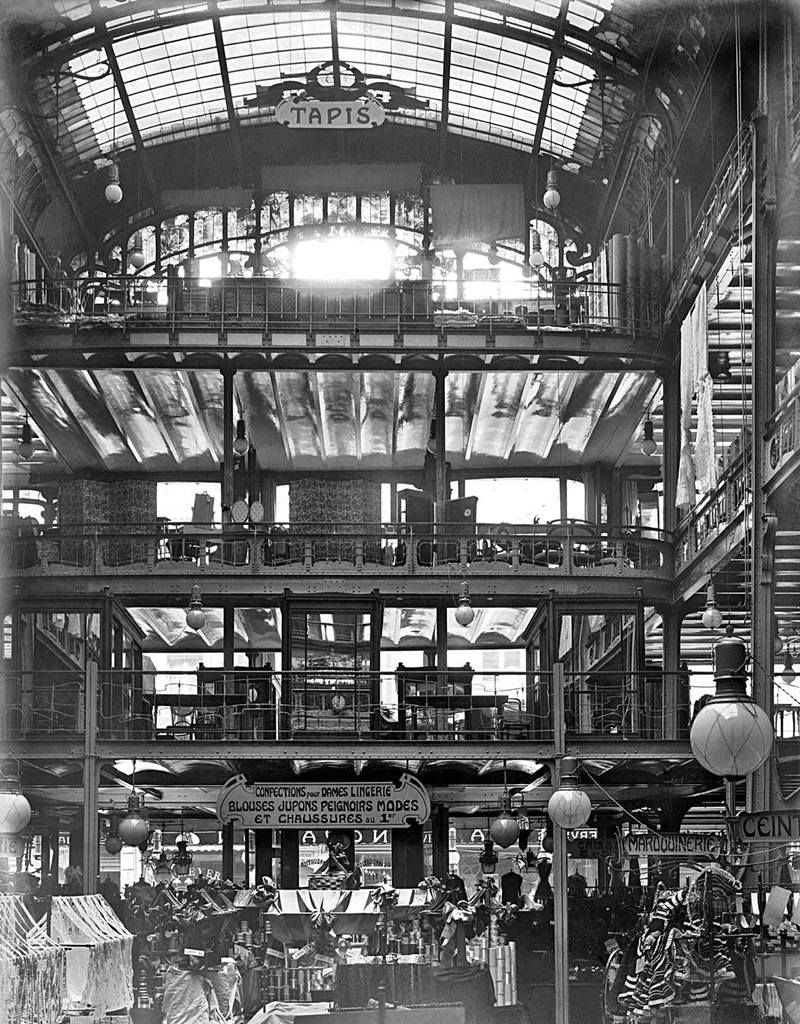

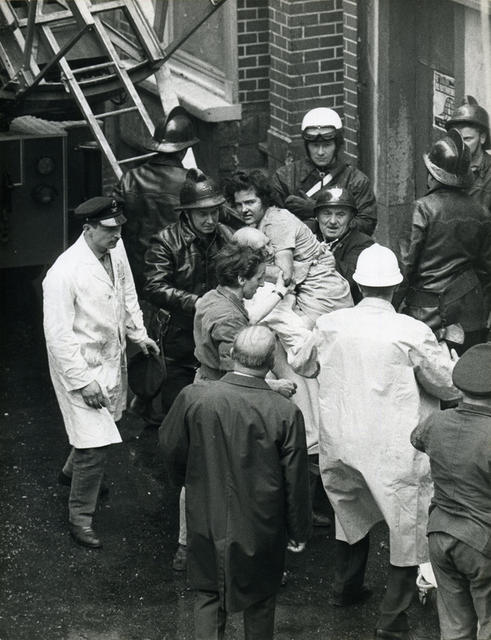

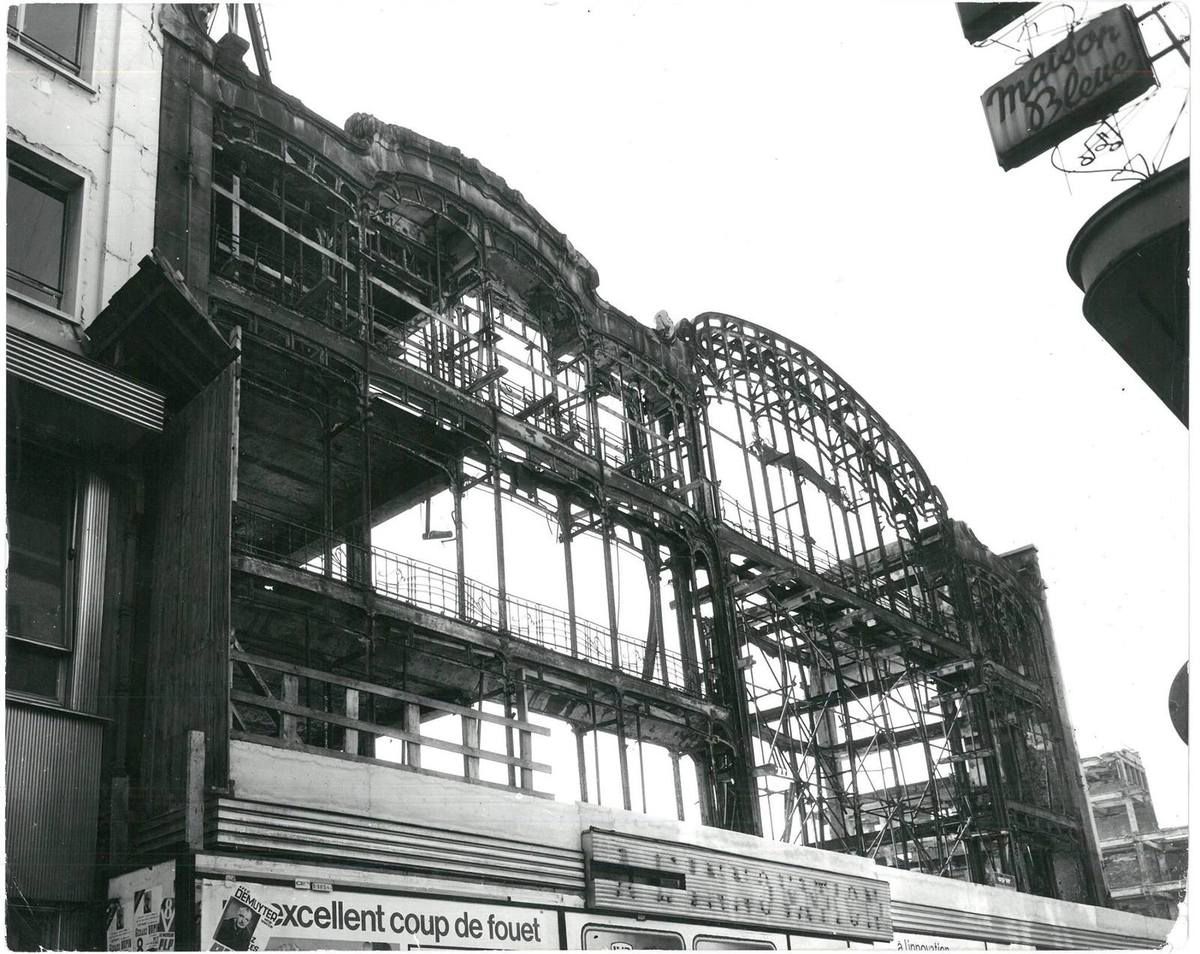

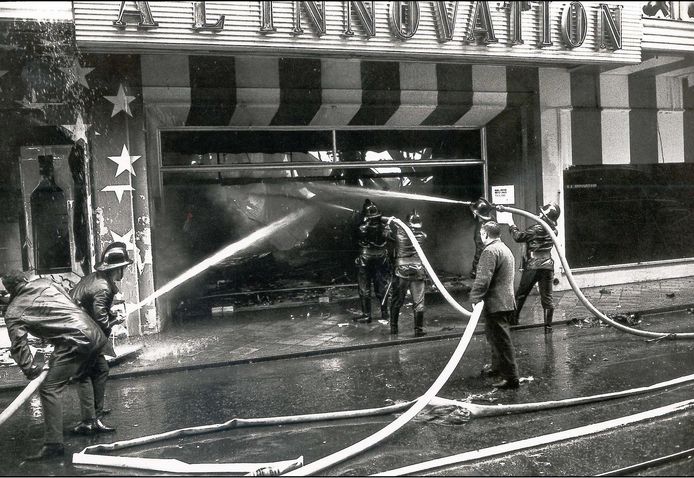

![[May 26, 1967] Flames over Brussels: The <i>À l'Innovation</i> Department Store Fire](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/EYnHrqQWAAAAOAu.jpg)

![[May 24, 1967] Heavyweight Champion (Avalon Hill's <i>Blitzkrieg</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670524box-672x372.jpg)

![[May 22, 1967] Parable in SF's clothing (The Space Trilogy, by C.S. Lewis)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670522covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 20, 1967] Field trips (June 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670520cover-449x372.jpg)

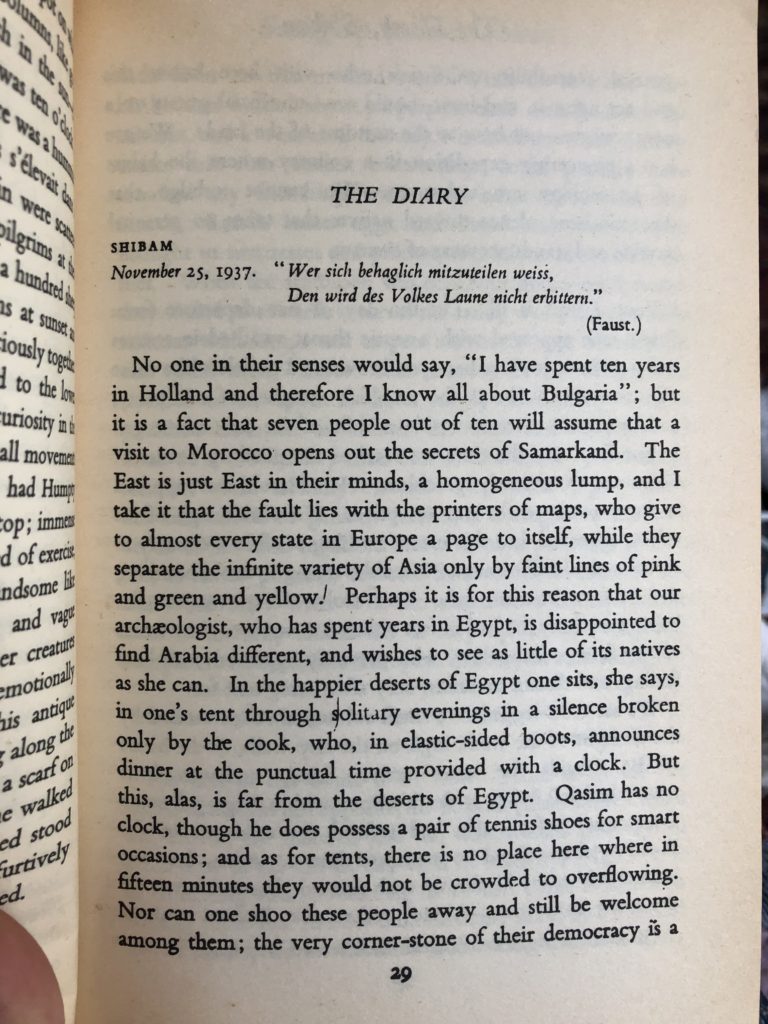

![[May 18, 1967] After Dune (the fantastic setting of Yemen)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/5443721933_cce05bca34_b-672x372.jpeg)

![[May 16, 1967] From the Sea to the Stars (May 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670516covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 14, 1967] Ben And Polly To The Departure Gate (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Faceless Ones [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670514benandpolly-672x372.jpg)

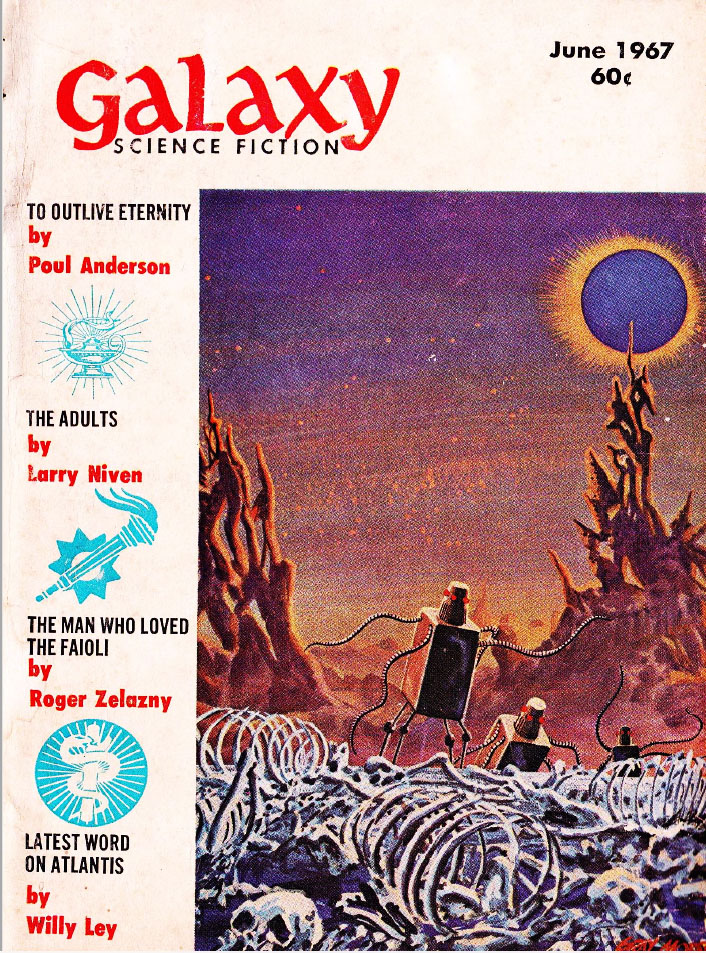

![[May 12, 1967] There and Back Again (June 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670512cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1967] Float Like A Butterfly, Sting Like A Bee (<i>The Green Hornet</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670510title-672x372.jpg)