by Cora Buhlert

A New Decade and a New Hope

It's January 1970, the start of a new decade, and at least in West Germany, it also feels like the start of a more hopeful time.

The new chancellor Willy Brandt and his social-democratic/liberal coalition government have been in power for not quite two months yet and the wind of change is already in the air, as the Brandt government has initiated talks with the governments of East Germany and other Eastern Bloc countries to thaw the ice of the Cold War a little.

And so the annual New Year's Eve celebrations felt a little cheerier, the fireworks were a little brighter and everybody seemed more optimistic, even though much of West Germany is currently covered in a thick layer of snow.

But before New Year comes Christmas and this year, Santa left two new books under my tree, both of which offer a glimpse into a future that is not quite as optimistic as West Germany feels at the moment.

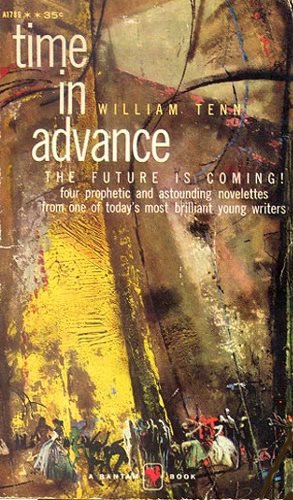

A Paranoid Nightmare: Drug of Choice by John Lange

One of the brightest rising stars of the thriller genre is John Lange. He burst onto the scene in 1966 with the heist novel Odds On and has been delivering entertaining thrillers, usually set in exotic locations and often laced with science fiction elements, at a steady clip since then. I reviewed two of them – Easy Go and Zero Cool – for the Journey.

Eventually, we learned that John Lange was the pen name of a young Harvard medical student named Michael Crichton, who released a novel under his own name last year. The Andromeda Strain, reviewed here by my colleague Joe Reid, was unambiguously science fiction and also drew on Crichton's medical knowledge, since it is about a deadly microbe from outer space.

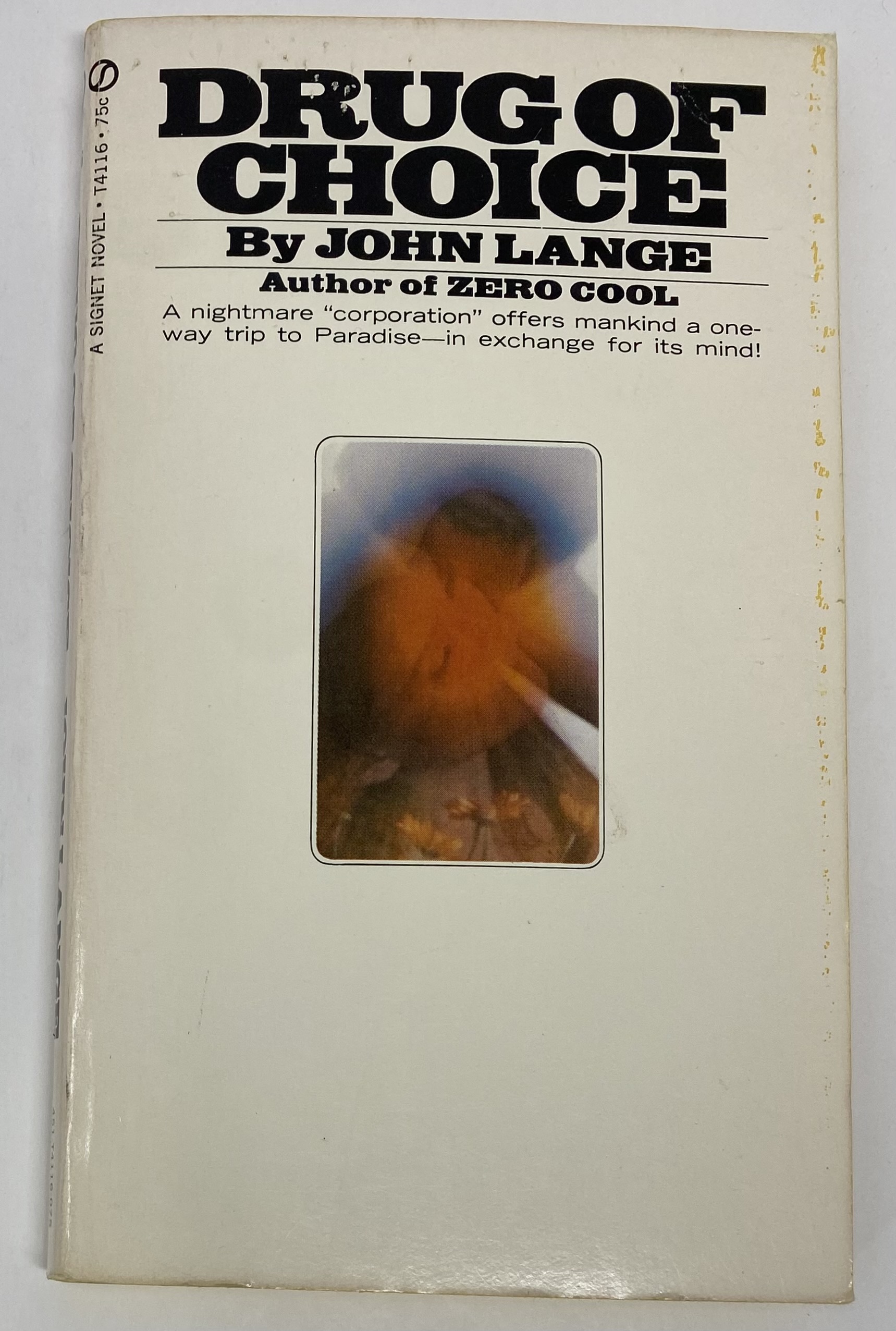

What is more, Lange/Crichton also wrote a medical thriller called A Case of Need under yet another pen name, Jeffrey Hudson. The novel deals with a controversial issue, namely illegal abortion and the fact that it often leads to the preventable deaths of young women, which is probably why Crichton chose a different pen name to distance it from his John Lange thrillers and the novels under his own name. In spite of the controversial subject matter, A Case of Need won a highly deserved Edgar Award last year.

But whatever name he writes under, John Lange a.k.a. Michael Crichton a.k.a. Jeffrey Hudson is always worth reading. And so I was excited to read his latest novel, Drug of Choice.

Drug of Choice once more draws on Lange/Crichton's medical experience, for protagonist Roger Clark is a medical resident at Los Angeles Memorial Hospital. One day, a Hell's Angel is brought in, comatose after a motorbike accident. It seems like just another day in the emergency room, until Clark notices that the biker has no visible injuries…. and that his urine is bright blue. Clark assumes that some unknown drug is to blame for the young man's condition. However, the next day the biker awakes from his coma as if nothing had happened… and the colour of his urine is back to normal.

The case is certainly strange, but Clark quickly moves on. But then it happens again. Up and coming actress Sharon Wilder is brought to the hospital, comatose for unknown reasons. And her urine is blue. This triggers Clark's inner Sherlock Holmes and he begins to investigate. Clark learns that both Sharon and the biker were patients of the same psychiatrist. Contrary to medical ethics, Clark also gets involved with Sharon herself and winds up accompanying her on holiday to San Cristobal, a new island resort in the Caribbean, which is billed as the perfect vacation spot.

San Cristobal indeed seems to be paradise and Clark enjoys wonderful days with Sharon Wilder. But absolutely nothing is as it seems at San Cristobal, for instead of a luxury resort, the hotel is just a few dingy rooms where the guests are kept in a state of comatose bliss by a mysterious drug, which also has the side effect of turning urine blue. Behind everything is the mysterious Advance Corporation… who want to recruit Roger Clark to work for them and they won't take "no" for an answer.

Similar to A Case of Need, Drug of Choice starts out as a medical thriller, dealing with a hot social issue, in this case drug abuse. However, once Clark gets to San Cristobal and sees the disturbing reality behind the glamorous façade, the novel takes a turn into Philip K. Dick territory – a world of paranoia, drugs and shadowy powers that one man cannot beat… or can he? Indeed, if you'd given me the novel in a plain brown paper wrapper and without an author name, I would have assumed that this was Philip K. Dick's latest novel. Except that from a purely stylistic point-of-view, Lange/Crichton is a better writer than Dick.

From the entertaining adventure thrillers of a few years ago via his Edgar winning A Case of Need to last year's The Andromeda Strain and now Drug of Choice, John Lange/Michael Crichton keeps getting better and better and is quickly becoming one of the most exciting new voices in both the thriller and science fiction genre.

Supposedly, Michael Crichton earned his doctorate last year, which means that the reason he started writing, namely to pay his way through medical school, no longer applies. Nonetheless, I sincerely hope that he will keep writing, under whichever name he prefers, because John Lange/Michael Crichton is too good a writer to lose him to medicine.

A paranoid nightmare of a thriller in the vein of the best of Philip K. Dick. Four and a half stars.

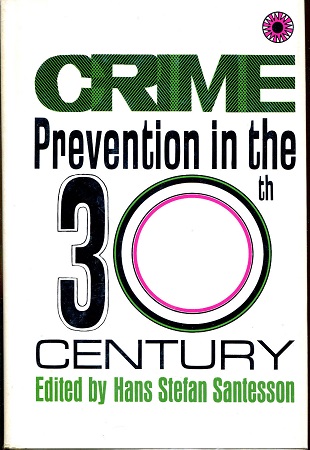

Crime Prevention in the 30th Century, edited by Hans Stefan Santesson

Another hot button issue of our times, particularly in the US, is rising crime rates that plague particularly the big cities and plunge their citizens into fear. However, crime rates are also rising in West Germany, albeit more slowly, and those crimes which most impact the average citizen such as burglary and theft also have fairly low detection rates, whereas the 1969 West German crime statistics boast high detection rates for offences such as abortion or sex between adult men (recently decriminalised) which many people believe should not be criminalised at all

In his introduction to the anthology Crime Prevention in the 30th Century, Hans Stefan Santesson, former editor of Fantastic Universe and The Saint Mystery Magazine and therefore familiar with both science fiction and crime fiction, addresses the fact that many people in the US and elsewhere fear rising crime rates, but also points out that crime isn't a new phenomenon, but has always been with us and always will. Just as there will always be a need for police officers and detectives to investigate those crimes.

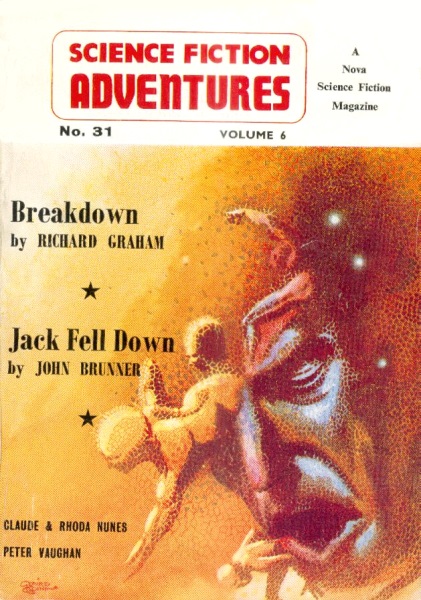

"Jack Fell Down" by John Brunner

First published in the March 1963 issue of Science Fiction Adventures, this novelette introduces us to Marco Kildreth, a cybernetically enhanced engineer who is out fishing in a ferocious storm on the Atlantic, when he makes an unexpected catch – a dead body. A closer examination reveals that the dead man did not drown, but was dropped into the sea from a great height. What is more, Marco recognises the dead man as one Jack Yang, member of a delegation from the colony planet Morthia who was on Earth for an important conference. Marco Kildreth not only happened to attend the same conference, but negotiations to give Morthia and its neighbour planet a so-called Builderworld, an automated factory planet to supply all needs of the population, were blocked by the Morthian delegation, giving Marco a motive to want to get rid of Yang.

Marco Kildreth did not murder Jack Yang. But after some investigations of his own, he has a pretty good idea who did…

John Brunner uses the structure of the traditional murder mystery to tell a greater story about the post-scarcity Earth of the future and the colony world Morthia which is governed by a genetically determined feudalism. The establishment of an automated Builderworld to produce anything the impoverished population of Morthia needs would threaten the elevated position of Morthia's ruling elite, which is why the Morthian delegation is vehemently opposed to this.

As a science fiction story, "Jack Fell Down" is an excellent look at one or rather several future societies and manages to create a vivid setting in only 39 pages. As murder mystery, however, it is unsatisfactory. We do learn who committed the murder and why, but the clues are never properly planted.

Two stars, mostly for the background world.

"The Eel" by Miriam Allen deFord

First published in the April 1958 issue of Galaxy, this story follows the titular Eel, a particularly slippery thief who is wanted on eight planets in three different solar systems. The Eel does not operate on his homeworld Earth, though Galactic Police there wants him, too, to extradite him to the worlds where he committed his crimes.

After twenty-six years, the Galactic Police finally get lucky and catch the Eel. There's only one problem. Where should he be extradited, considering that he committed crimes on eight different planets, all of which are extremely interested in putting him on trial and punishing him according to their respective laws?

The Eel is finally extradited to Agsk, a world which does not have the death penalty, but which punishes criminals by executing the person they love most in front of their eyes. There is only one problem. The Eel has neither family nor friends and apparently never loved anybody except for himself. But just when the Agskians are about to execute the person the Eel loves most, namely himself, the Eel reveals that he has one more ace up his sleeve…

"The Eel" perfectly shows off Miriam Allen deFord's gift for dark humour and the solution for how the Eel wiggles out of his punishment is ingenious.

Five stars.

"The Future Is Ours" by Stephen Dentinger

The first mystery posed by this story is "Who on Earth is Stephen Dentinger?" The resolution to that one is quite simple: Stephen Dentinger is a pen name of prolific mystery writer Edward D. Hoch (the "D" stands for Dentinger) who also dabbles in science fiction and horror on occasion.

The story follows a police officer named Captain Felix who is about to test drive the time machine, or rather chronological manipulator, invented by one Dr. Stafford. Captain Felix plans to travel to New York City in the year 2259 AD to learn about new techniques for police work. What he finds, however, is not at all what he had expected…

This very short (only three pages long) tale is a typical example of the "twist in the tail" story that was popular twenty-five years ago, but has become rare since. This type of story relies on the twist being good and in this case it is.

Three stars.

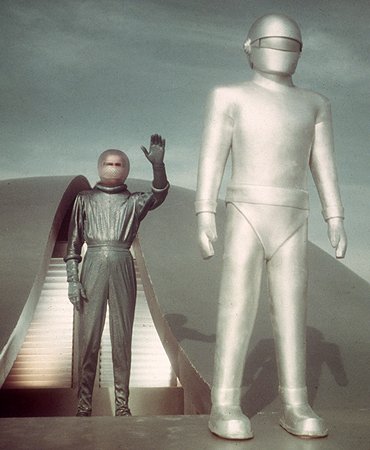

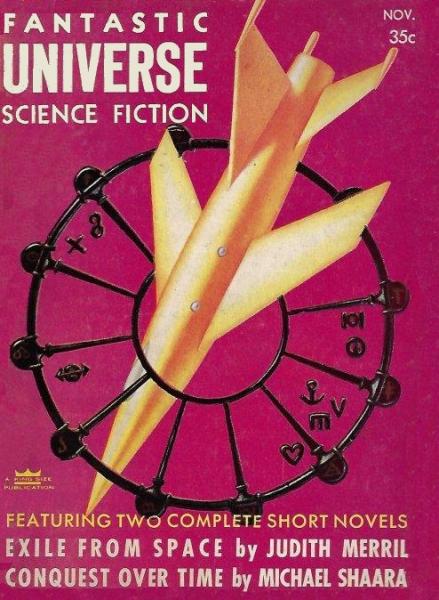

"The Velvet Glove" by Harry Harrison

First published in the November 1956 issue of Fantastic Universe, this novelette follows Jon Venex, an unemployed robot living on a future Earth beset by anti-robot prejudice. One day, Jon responds to a job ad asking for a robot with his specific skills, and gets much more than he bargained for, when he finds himself strapped to a bomb and forced to work for a gang of drug-runners. Worse, he finds the remnants of his predecessor.

Jon uses all his robotic skills to alert the authorities without violating his innate programming never to harm a human being. But even if he succeeds, will a robot ever be treated as an equal on this future Earth?

Like John Brunner's "Jack Fell Down", Harry Harrison uses the structure of a crime story to present his vision of a future Earth. However, Harrison is a lot more successful at blending science fiction and crime fiction and "The Velvet Glove" manages to work as both. What is more, Jon Venex is a very compelling protagonist.

Four stars.

"Let There Be Night!" by Morris Hershman

Morris Hershman is another author better known for mysteries than for science fiction. His vignette "Let There Be Night!" first appeared in the November 1966 issue of The Saint Mystery Magazine.

Curt Yarett is unhappily married to Edna, an alcoholic. However, alcohol abuse is a criminal offense in this brave new world of the future and so Curt has the perfect way to get rid of his wife by reporting her to the authorities…

The focus of this brief vignette is less on the "crime" committed and more on changing mores and laws, particularly with regard to intoxicating substances and how what is illegal in one time may well be considered perfectly acceptable in another. Considering the rise in drug use in recent years, this is certainly an important topic. However, the story itself is too brief to truly delve into the questions it raises.

Two stars.

"Computer Cops" by Edward D. Hoch

Edward D. Hoch puts in his second appearance in this anthology—this time under his own name—with this tale about a crime-fighting agency called the Computer Investigation Bureau, CIB for short, fighting electronic crime in the not too far off future of 2006 AD. It is one of the two non-reprints in the anthology.

One day, Carl Crader, director of the CIB, is summoned by Nobel Kinsinger, one of the richest men in the world, for someone has been using his SEXCO machine, a computer used to buy and sell stocks at the New York Stock Exchange, without authorisation. Crader quickly homes in on two likely suspects, John Bunyon, Kinsinger's assistant, and Linda Sale, his secretary. However, the truth turns out to be quite different…

Of the various stories in this anthology, "Computer Cops" matches the theme – how will law enforcement agencies investigate and hopefully prevent crime in the future – the closest. "Computer Cops" is very much a so-called police procedural, i.e. a type of mystery which delves into the methods the police uses to investigate crimes. To me, it felt very much like a futuristic version of the popular West German pulp crime series G-Man Jerry Cotton. "Computer Cops" also succeeds both as a science fiction and a crime story.

However, there are two problems with this story. The first is that the female characters are relegated to secretaries in miniskirts or bodystockings – all the investing and investigating is done by men. Compare this to Tom Purdom's "Toys", which features a female police officer, and John Brunner's "Jack Fell Down", which features a woman as the Secretary of Extraterrestrial Relations as well as a female professor of sociology and which also casually notes that not everybody in the future is white.

The other problem with this story is that 2006 AD is not very far off at all, only thirty-six years in the future, which means that many of us may well live to see it. As a result, this also means that many of the predictions that Hoch makes, either as part of the plot or casual off-hand remarks, may well turn out to be completely and hilariously wrong. Of course, it's reasonable to assume that New York City's World Trade Center, currently under construction and the tallest building in the world, once completed, will still be standing in 2006. Using computers to make deals on the stock market seems quite likely and billionaires getting involved into politics to the point of bankrolling or even leading invasions of independent countries sadly isn't too farfetched either. However, the assumption that Fidel Castro's regime in Cuba will crumble in the next few years may well turn out to be premature.

Probably the most successful blend of science fiction and crime fiction in this anthology.

Three stars.

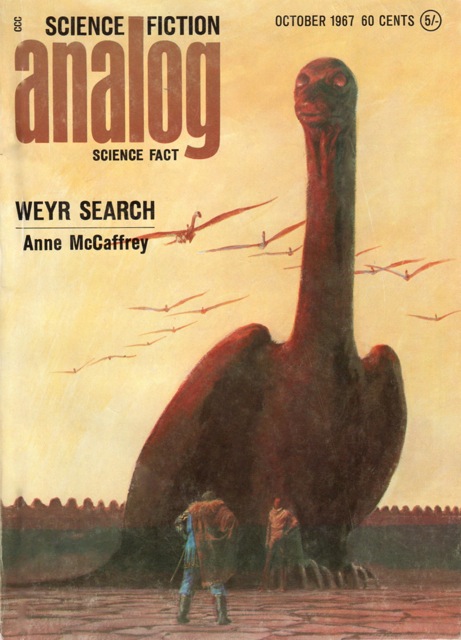

"Apple" by Anne McCaffrey

The second new story is Anne McCaffrey's novelette, which opens with a seemingly impossible crime. A priceless fur coat, sapphire necklace, haute couture gown and jewelled slippers, have been stolen from the display window of a high-end department store in the brief time lag between security camera recordings.

The only way this crime could have been committed is via telekinesis. This is what brings in telepath Daffyd op Owen of the North American Parapsychic Center, an organisation which identifies and trains people with parapsychic talents and also works to end prejudice against them. All Talents at the Center were present and accounted for, when the theft occurred. This means that the thief must be a so-called "wild Talent", i.e. a Talent who's unregistered and unknown to the North American Parapsychic Center. Worse, this crime endangers the passing of a bill providing legal protection for Talents.

So the hunt is on for the telekinetic thief. Daffyd op Owen's Talents quickly zero in on an apartment block in a deprived part of town and find an apartment full of stolen goods – but not the thief. One of the Talents tracks the young woman – it is quickly determined that the thief must be female, because a man would only have taken the necklace and fur coat, but not the dress or the shoes – to a train station, where she uses her abilities to throw a baggage cart at her pursuer and crushes him. In spite of the girl killing one of his people, op Owen wants to bring her in alive and unharmed. But sometimes, there are no happy endings…

In recent years, Anne McCaffrey has been more interested in the dragons of Pern than in good old Earth, but she has also written a few stories about the Talented and their struggle for recognition.

"Apple" clearly shows McCaffrey's strengths as a writer. The action scenes are frenetic and there is some interesting characterisation, too, in the scenes where op Owen and his police counterpart Frank Gillings butt heads. However, this story also displays the issues I've always had with McCaffrey's work, namely latent prejudice that underlies much of it – ironic in a story that is about overcoming prejudice. And so the thief is the proverbial bad apple, because she is a) poor and b) of Romani descent, though McCaffrey uses a much less polite term.

A otherwise good story, marred by some of McCaffrey's persistent issues.

Three stars.

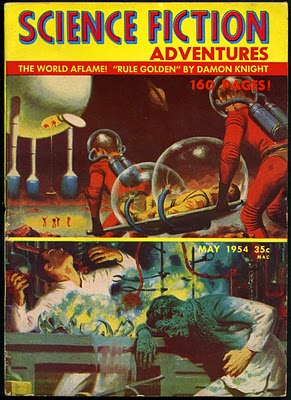

"Rain Check" by Judith Merril

Originally published in the May 1954 issue of Science Fiction Adventures, "Rain Check" follows a shapeshifting alien who was brought back from Mars and is being taken to see the US president aboard a secret express train. However, the alien escapes during a refuelling stop – not for malicious reasons, but out of pure curiosity.

After some time spent as a large package on the platform, the alien takes on the shape of a human woman and wanders into an all-night diner. However, the alien's appearance attracts the attention of Mike Bonito, the man behind the counter, who promptly tries to chat up what he thinks is an attractive woman.

Turns out Mike Bonito is a civil defence warden, when he's not bartending, and was specifically told to be on the lookout for the runaway alien, though all they have to go on is a vague description of a male human. However, there will be an important meeting of all civil defence wardens in the city later that day. The alien, now named Anita, gets herself invited to come along, after manifesting a civil defence badge.

The American astronauts who captured the Martian believe that the alien's special abilities will help them win a war. However, "Anita" has a reason of her own for wanting to explore Earth.

This is not so much a crime story, but a cloak and dagger type spy story. Of course, being a Judith Merril story, it's also very well written and "Anita's" observations about life on Earth and particularly the persistent rain, so alien to a Martian, are fascinating.

Five stars.

"Toys" by Tom Purdom

"Toys" begins with a hostage situation. A group of children and their "pets" – an elephant, a gorilla, two dragons (created via genetic engineering) and two tigers – have taken a family hostage and demand that a committee made up of parents negotiate with them. Meanwhile, various adults are congregating outside and threatening to enter the house and beat up the children.

Police officers Charley Edelman and Helen Fracarro are called in the deal with the situation. They storm the house and find themselves fighting off both the "pets" and the children who have transformed their educational toys such as genetic engineering kits into surprisingly effective weapons. Will Charley and Helen be able to diffuse the situation before someone – adults, kids or pets – gets killed?

Our founder Gideon reviewed this story upon its original publication in the October 1967 issue of Analog and also adds some interesting background notes from author Tom Purdom who is a good friend of the Journey.

"Toys" is an action-packed story and offers some interesting speculation about how even in an increasingly affluent world, there will always be those who have less than others, even if they would have be considered wealthy as recently as thirty or forty years ago. Anne McCaffrey's "Apple" makes a similar point and is also largely set in a modern housing estate like those that are increasingly replacing the slums of old, raising the living standards of the working class, while not changing their economic status.

"Toys" also succeeds at blending science fiction and police procedural. Charley and Helen are compelling protagonists and I wouldn't at all mind a series of Charley Edelman and Helen Fracarro futuristic police procedurals.

That said, I also had a big problem with this story and that is that I intensely dislike stories about evil children. Now fear of children and young people is a common theme in science fiction. With the children of the postwar baby boom now in their teens and early twenties, an age when they begin to have political opinions and demands that don't necessarily match their parents', we have seen an uptick in dystopian stories about tyrannies set up by young people such as Logan's Run by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson or the movie Wild in the Streets. But there are older examples as well such as the 1944 story "When the Bough Breaks" by Lewis Padgett a.k.a. Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore about a couple terrorised by a superhuman baby. "Toys" certainly fits into the tradition of science fiction terrified of young people having a mind of their own. But though it is well written, I just don't care for stories of this type.

Three stars.

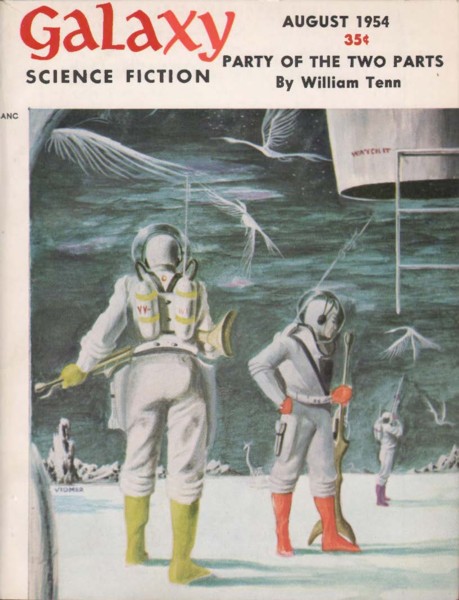

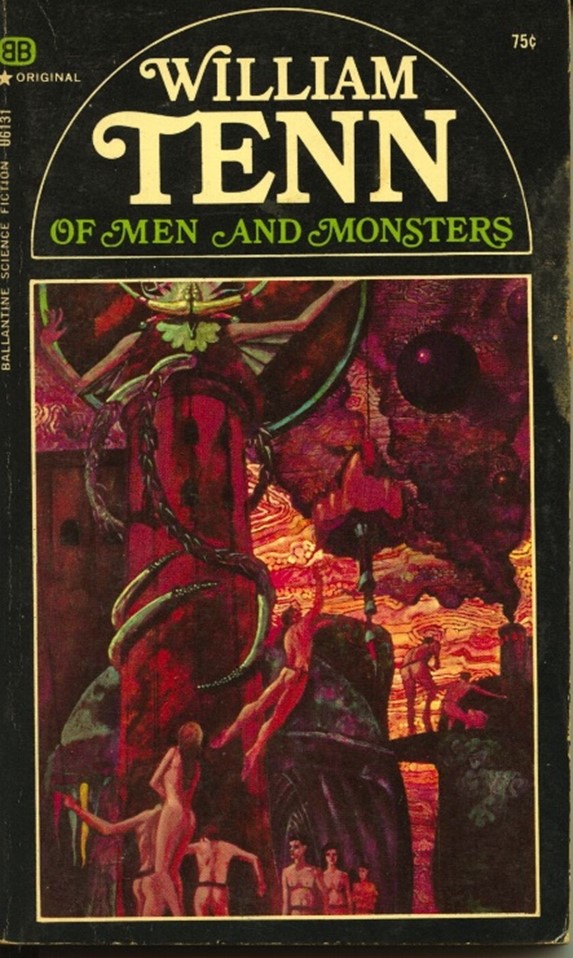

"Party of the Two Parts" by William Tenn

First published in the August 1954 issue of Galaxy, this story is an epistolary tale in the form of a galactogram from one O-Dik-Veh, a patrol sergeant on duty out in the galactic boondocks, to Hoy-Veh-Chalt, desk sergeant at headquarters and O's cousin, wherein O recounts his latest case.

O has been assigned to watch over the third planet of Sol a.k.a. Earth to make sure that its inhabitants don't blow themselves up before they have matured enough to be inducted into the great galactic community. Much like "Anita" from Judith Merril's "Rain Check", O finds Earth damp and unpleasant. What is more, the patrol office had to be erected on Pluto, a planet O describes as "a world whose winters are bearable, but whose summers are unspeakably hot". These few paragraphs tell us both clearly and very entertainingly that whatever O and Hoy are, they are very much not human. O also refers to their commissioner as "Old One" and is mentioned to have tentacles, so I imagined O and Hoy as something like H.P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu, only as a cop.

O's latest problem started when L'payr, a career criminal from the planet Gtet, escapes on the eve of the trial that will put him behind bars for life, steals an experimental spaceship and ends up on Earth, specifically the suburbs of Chicago. However, L'payr, who is basically a telepathic amoeba, can't survive on Earth for long, so he needs supplies to get his ship spaceborn again. So L'payr telepathically lures high school chemistry teacher Osborne Blatch to his hideout to trade alien pornography for chemical components from the high school lab. Though Blatch is less interested in the pornography – it is amoeba pornography, after all – and more in learning about where the mysterious puddle-shaped alien came from. L'payr, however, doesn't stick around to discuss the state of the galaxy with Blatch, but legs it once he has all the chemicals he needs. Blatch, meanwhile, finds an excellent use for the amoeba pornography he acquired and publishes a biology textbook with detailed illustrations of amoebas reproducing.

We haven't heard much of William Tenn lately, ever since he became a professor of English at Pennsylvania State University. This is a pity, because Tenn's satirical science fiction has always been a delight. And indeed "Party of the Two Parts" starts out utterly hilarious, but then gets bogged down in a lengthy debate whether pornography is pornography, if it doesn't titillate anybody due to not depicting remotely the correct species and whether a crime has been committed that allows for L'payr to be extradited back to his homeworld. The way that O entraps L'payr and L'payr – with some help from Osborne Blatch – tries to wiggle out of his extradition are both ingenious and funny, but the story is still longer than it needs to be.

Four stars.

Police Work of the Future

All in all, this is a solid anthology of stories blending science fiction and crime fiction. That said, the title Crime Prevention in the 30th Century is something of a misnomer, since the stories are more focussed on police officers solving crimes or criminals committing crimes and trying to evade the law than on the prevention of crimes. What is more, none of the stories are explicitly set in the 30th century.

Nor is this anthology particularly useful as a blueprint for policing techniques of the future – only Edward D. Hoch's "Computer Cops" even remotely offers a look at what actual police work might look like in the future. However, Crime Prevention in the 30th Century is not a police academy textbook, but a science fiction anthology and as such it offers an entertaining look at several very different futures. I find that the stories which are at least somewhat humorous work better for me than the more serious tales.

Three and a half stars for the anthology as a whole.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

![[January 12, 1970] A Glimpse into the Future: <i>Drug of Choice</i> by John Lange and <i>Crime Prevention in the 30th Century</i>, edited by Hans Stefan Santesson](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/CRMPNTRY7D1969-310x372.jpg)

![[June 14, 1968] Men, Women, and Monsters (June 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680614covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1967] Music To Read By (July 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fantastic_196707-2-1.jpg)

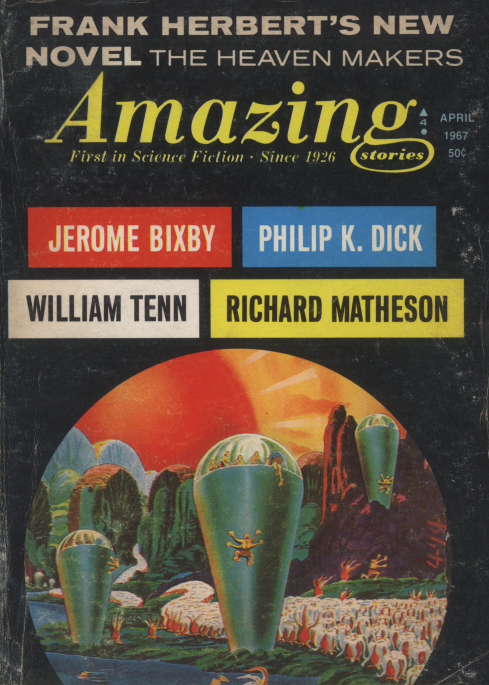

![[March 14, 1967] Family Matters (April 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/amazing-apr-1967-cover-489x372.png)

![[January 18, 1966] New Discoveries of the Old (<i>Out of the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Out-of-the-Unknown-Titles.jpg)

![[July 16, 1965] To Fresh Woods (August 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650716cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 6, 1965] Back To Our Roots (<i>New Writings in SF4</i> & <i>Over Sea, Under Stone</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/New-Writings-and-Over-Sea-Under-Stone.jpg)

![[September 9, 1963] Great Expectations (October 1963 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630909cover-444x372.jpg)