by Lorelei Marcus

Dark Age for the Boob Tube

Mop-tops and Munsters are on the rise, replacing the theoretical with the fantastical. With the end of pioneering anthology shows like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, television has transformed into a wasteland for science fiction. Gone are the prospective and predictive contents depicting the wonders of space, sea, and air. Instead, we have spies, saIlors, and sorceresses clogging our TV screens – with mixed results.

But there is hope for the science fiction aficionados of the world. Upcoming productions like Lost in Space and Star Trek hold promise for the revitalization of the genre on TV. My father and I are both eagerly awaiting this new dawn. However, Lost in Space is just starting, and Star Trek is at least four months away (there is rumor of it being a mid-season replacement starting in January 1966).

Luckily, there is a plethora of now-classic science fiction movies that came out in the last decade that we missed the first time around, but which are occasionally revived at theaters and drive-ins. These shows allow us to sate our viewing appetite while we wait for the TV crop to come in.

That's how we ended up in a dingy old theater on the edge of town watching a double feature billed as "They Came from 1951!" – The Day the Earth Stood Still and When Worlds Collide shown back to back. It was an interesting experience, to say the least.

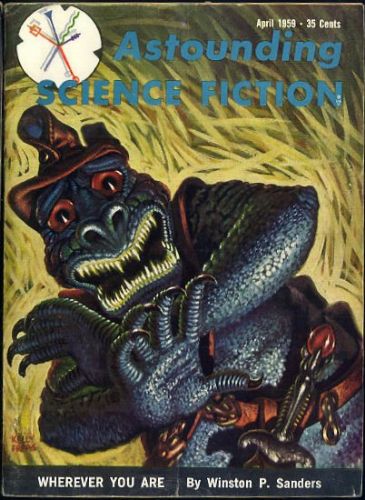

The Day the Earth Stood Still

The story of The Day the Earth Stood Still is probably well known to everyone. However, since my dad and I managed to go in completely unaware of anything about the movie, other than what we could discern from the poster, here's a brief summary:

The Day the Earth Stood Still is a black and white film about an alien named Klaatu who comes to Earth in a flying saucer (those being all the rage in 1951) to deliver a momentous message to humanity. He looks just like us despite having traveled more than 250 million miles to get to the Earth.

To be fair, Klaatu could have picked a less menacing gesture to start with.

It's a good thing that tank crew had pistols!

After a hostile reception, Klaatu refuses to convey his message to anyone but an assemblage of all the world's leaders. When this proves impossible for primitive Earth to manage, Klaatu escapes military custody and tries to assimilate with human society so as to find an alternate solution.

Wow! Bill aids owner on foreclosure!

"Land sakes! There's an alien among us! Better not tell Opie – it'll give him nightmares…"

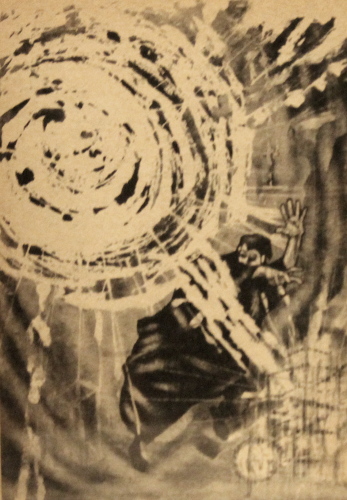

Hysteria ensues as the media report on the unleashing of a twisted, horrific alien monster on the streets of D.C. With the aid of a boy, his mother, and a scientist, Klaatu must find a way to connect with all of humanity, while dodging the agents of the U.S. Government, to prevent the destruction of our world – which will happen one way or another if Earth does not cease its warlike ways.

"I'd like to meet all of your assembled leaders." "Oh, you mean like a United Nations?" "Sure." "Nah. Too much trouble."

Ultimately, the film is a cautionary tale which left me with two overriding messages: "Don't shoot on sight" and "Listen to children, women, and scientists" (scientists can be of any gender).

"Are you a scientist?" "What gave it away?"

I actually appreciate what this movie was trying to say, but its execution was so heavy-handed, populated with more straw men than Iowa, it weakened the message. The US military is portrayed as so hilariously incompetent, it creates inconsistencies in the plot. I'm left wondering how the army can afford to send every jeep and tank in its arsenal to capture Klaatu but only leaves two men to guard his spaceship. What could have been a nuanced social commentary on the moral ambiguity of the U.S. Government's policies turns into a laughable mess.

"Night, Tom…Jerry. I'm sure you two will be just fine guarding that spaceship next to the big robot!"

There's the rest of the army. A bit too late…

The science is slightly better, though the idea there could be advanced life on other planets in our solar system feels incredibly old fashioned in light of the recent Mariner mission. [The distance he traveled suggests he came from Mars, but he may not be a Martian – there may simply be an alien outpost on Mars (ed.)]

However, the movie did get the special effects and set design right. I was particularly impressed by the slick interior of the spaceship. The glowing buttons and glass instruments are both beautiful and the embodiment of the science fiction aesthetic.

The latest in blinky light and glass chic!

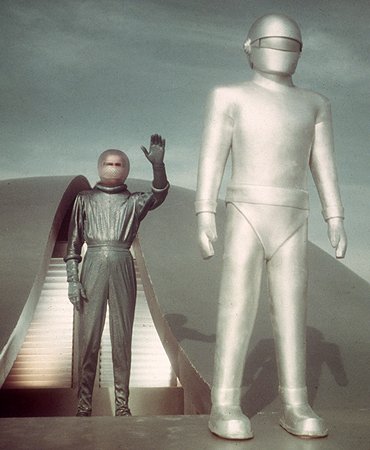

I was also entertained by the design of Gort, Klaatu's all-powerful robot. While silver mittens and underwear over a metallic motorcycle suit would not have been my first fashion choice, it's charming none the less.

"I'd like to say it's been a pleasure, but…"

The acting and pacing were fine. I especially enjoyed the performance of Patricia Neal, the tough mother character, and also Michael Rennie (clearly inspired by Robert Oppenheimer). Young Billy Gray is good too, more remiscent of Kurt Russell than Ron Howard.

You know that awkward moment when you're stuck in an elevator with a stranger?

"I like this guy. He seems like a good guy. Find me more like him."

In total, the movie was a thoroughly OK experience. It could have done a lot better in many places, but in the end, it did make an effort, which is more than can be said for many SF films these days.

Three stars

When Worlds Collide

When Worlds Collide's title literally exploded across the movie screen with tongues of flames blazing in glorious color accompanied by a screeching score. No five year olds were wriggling in their seats anymore. With an intro like that, and with producer George Pal's name in big print, this move held real promise…

…and then the camera zoomed on a giant Bible, which flipped to a passage from the tale of Noah's Ark, to keep us from missing the theme of the movie.

Apparently, subtlety wasn't a widely known concept in the early '50s.

But I still had hope. After the dramatic introduction, the story began in a South African observatory in which an astromer glances through a telescope and realizes that, by God, he's confirmed the end of the world!

"You see it too, right, old chap?"

Dave Randall, professional aviator and the movie's protagonist, is ordered to deliver these findings in complete secrecy to an astronomer in the United States. Upon doing so, and meeting said astronomer's lovely daughter, he is let in on the secret: Bellus, a "star" (just twelve times more massive than the Earth) and its lone Earthlike planet, Zyra, are on a direct collision course with our world. We have only eight months to prepare.

"My, you are dull!"

I turned to my father, who is much more knowledgeable of orbital mechanics than I am, and asked, "Is that even possible?" To which he responded, "No." And then all the five year olds turned around and shushed us.

This was only the first of many such instances in this movie. Willy Ley, it isn't.

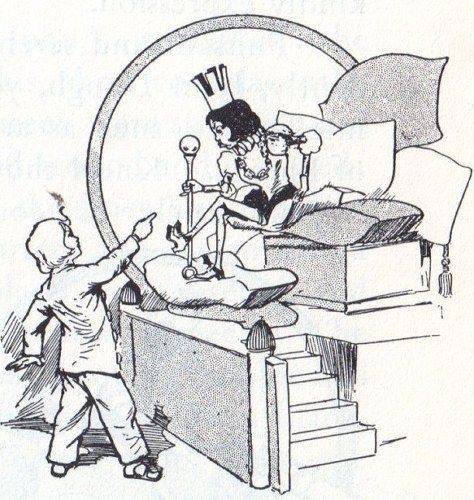

The astronomer presents this information to the United Nations and claims the only hope is building a spacecraft to fly to Zyra before Bellus destroys the Earth. The UN quite literally laughs in the astronomer's face, and thus he turns instead to private investors to make the Modern Noah's Ark a reality.

"Sit down, Mr. Addison! And shut that talking horse up while you're at it!"

New at Walt Disney's Tomorrowland!

Some of the investors provide their funds freely, but one rich man only backs the project after securing the promise of passage on the ark. The ensuing scenes of candidate selection for the engineering team and the commencement of ark construction are intertwined with a typical love triangle between Randall, the astronomer's colorless daughter, and her fiancee, Tony. These bits fall flat; indeed, by the end of the movie, Tony and Randall have far more chemistry with each other than the daughter. And you can imagine the dismay I felt at hearing the names "Tony" and "Randall," yet knowing that the person bearing both of those names was nowhere to be seen.

Tony & Randall: the sparks fly.

And that isn't the worst part of the movie! The story is progressively more convoluted and unbelievable (and worse, rather dull). The selection of the Ark's passengers becomes increasingly arbitrary despite the earlier emphasis given on relying on a random lottery. The science is atrocious, the characters shallow, the dialogue lousy.

"Sure, space is at a premium, but let's take this tyke and his dog!

"And this couple! I mean, they're in love and all!

"But this guy? I know he paid for all of this, but he's a jerk. He needs to die."

"Mein Fuhrer! I can walk!"

But the film's biggest fault, out of everything, is its lack of vision. If The Day the Earth Stood Still is a progressive film, When World's Collide is reactionary. The women passengers/technicians and the all-male engineer corps are always segregated. All of the passengers are strapping young college students. All seem to be of a similar class. And they are all white.

The audience at this point in the film.

I can understand wanting young candidates to weather the harshness of space travel, but to exclusively choose young colonists discounts the immense wisdom and knowledge held by the old. The men and women colonists are equal in number, but that has nothing to do with the scientific prowess of the women; rather, this is just to ensure that every man has a wife.

And even setting aside the morality of excluding all but the lily white from the candidate pool, it's a fatal mistake biologically. If a colony can only start with 40 people, it needs as diverse a gene pool as possible to prevent the perils of inbreeding.

Never mind that. What's important is that a small cadre of white, rich, Christian youngsters inherits the mantle of humanity.

When Worlds Collide is a celebration of the worst parts of society in the 1950s. I can look past the bad acting. I can look past the gratuitous religious imagery. And I can even ignore the fact that the completely alien world has perfectly breathable air. But I cannot excuse the lazy and offensive message this film chose to convey.

The only thing that keeps this movie from getting a one-star rank is its production values. The special effects are incredible, with some of the best painted backgrounds I have ever seen in a movie. The Earth's destruction sequences are also good, what little we get of them. For a movie about the end of our entire world, George Pal spent an awful long time filming the inside of a shaking office set… Nevertheless, judged on visuals alone, When Worlds Collide is impressive.

What we paid to see.

If only it weren't so terrible everywhere else.

Two stars.

Emerging into the Light

Kvetching aside, I don't regret watching either of these two movies. It gave me a great perspective on the history of science fiction on the silver screen, and it was interesting noting the impact of these two blockbusters on subsequent stories, both on television and in the movies. I'm particularly keen to see if any elements of these movies live on in upcoming releases, from Roddenberry's Star Trek to Kubrick's upcoming 2001 (formerly Journey Beyond the Stars). Only time will tell. Until then,

This is the Young Traveler, signing off.

We'll be discussing these movies and more at our next Journey Show: At the Movies!

![[September 18, 1965] Disastrous! (<i>The Day the Earth Stood Still</i> and <i>When Worlds Collide</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650918s15-672x372.jpg)

.jpg)