by Victoria Silverwolf

Did You Check the Card Catalog First?

If you're like me, when you enter a public or school library, or a bookstore, or any other place where volumes of written material are available for perusal, you wander around from place to place without any particular goal in mind. Of course, sooner or later you're going to wind up at the science fiction section. But along the way, you might find other kinds of fiction and nonfiction to pique your curiosity.

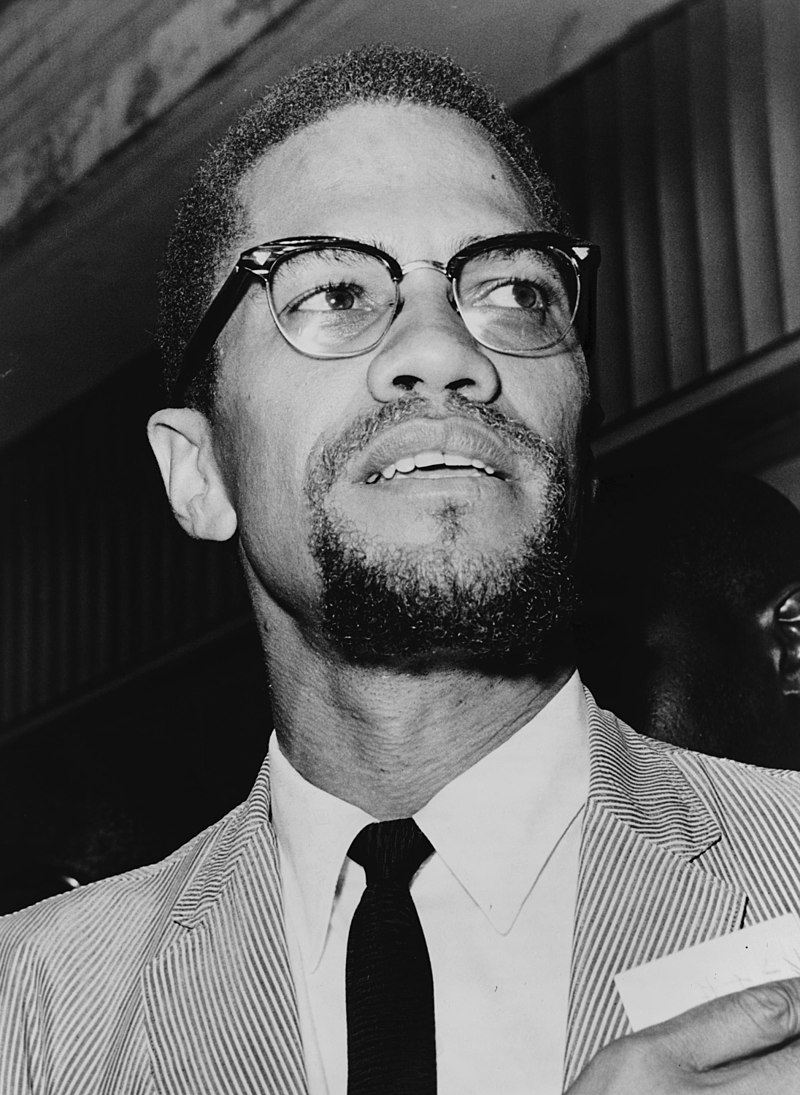

Students hard at work at Brigham Young University.They're probably not reading science fiction.

I thought about this pleasant little habit of mine when I looked at the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow. The stories and articles reminded me of other categories of writing. Take my hand, and we'll stroll through the paper corridors of this miniature book depository and find out what wonders await us.

Cover art by George Schelling.

What Size Are Giants?, by Alexei Panshin

Category: Westerns

We start off near novels by Zane Grey and other chroniclers of the Old West. This rootin', tootin' yarn begins with a gal settin' by herself readin' a book (appropriately enough) and not realizin' that she's about to be run over by a stampedin' herd of wild critters. Luckily for her, a fella in a covered wagon comes by and saves her. He's sort of a medicine show kind of city slicker, of the type that the local settlers don't cotton to.

Drawin' by Norman Nodel. That's a mighty funny lookin' horse you got there, friend.

OK, let me knock it off with the dialect before I drive both of us crazy. We're really on a colony planet, one of many settled about a century ago, when a large number of gigantic starships fled Earth just before a global war destroyed all of humanity. The colonists survive at a low level of technology, while the people who remain aboard the ships enjoy much more advanced devices. The colonists envy and resent the starship folk, and the people on the vessels look down on the settlers as peasants.

Our hero sneaks off one of the ships and lands on the planet, intending to help the colonists with better goods, and to encourage trade between isolated communities. Along for the ride is his buddy, an intelligent, talking bird. (The only explanation for this animal is that it's a one-of-a-kind mutant, which is a little hard to swallow.)

Things don't work out too well. Not only do the settlers figure out the man is one of the hated people from the starships, but he is also tracked down by an enforcer from the vessel, because interfering with a colony is a serious crime.

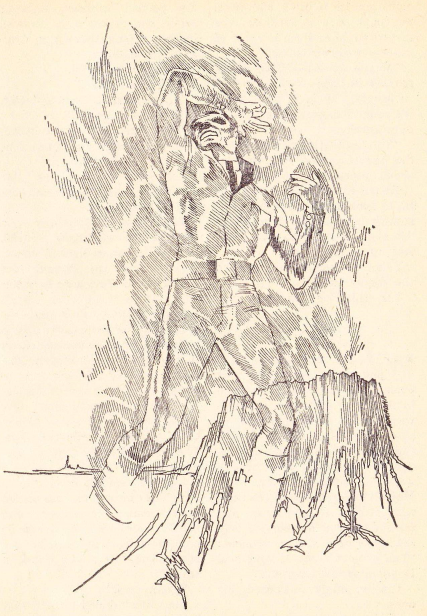

A very accurate rendition of the author's description of this unpleasant character.

Complicating matters is the fact that the stampeding beasts are about to go on the rampage again, threatening to destroy the local village and everyone in it. It all builds up to an exciting climax, as our tomboy heroine comes to the rescue.

Ride 'em, cowgirl!

This is a decent enough adventure story, if not particularly outstanding in any way. The author's style is plain but serviceable. It'll give ya somethin' to look at while you're sittin' around the campfire, waitin' for Cooky to rustle up some coffee and beans.

Three stars.

The Effectives, by Zenna Henderson

Category: Religion

Not far away from the Bibles, Korans, Torahs, and other sacred texts, we find this work of inspirational fiction from a skilled author known for the use of spiritual themes in her tales of the People.

Illustration by John Giunta.

KVIN (as shown above) is a devastating illness of unknown origin. Those who suffer from it die very quickly after feeling the first symptoms, which vary from person to person. The only treatment is to completely replace the victim's blood with donations from healthy volunteers. This doesn't always work, however.

There's a peculiar geographic pattern to the cure rate. It never works in the San Francisco area; works half the time near Denver; and is always effective at a particular area near a medical research center. A troubleshooter arrives at the place and tries to figure out what's going on.

The center is near a religious community that has turned its back on the modern world, something like the Amish. They supply the blood donations. There is no such community in the San Francisco region, and half of the blood donations at the Denver area come from such a community. Could there be a connection with the cure rates? The troubleshooter, a hardcore skeptic, performs a risky experiment in order to find out.

How you react to this fable may depend on your religious beliefs. You may think that the author has stacked the cards too much in favor of faith over materialism. The troubleshooter is something of a stereotype of the stubborn atheist, although I'll have to give the writer credit for depicting him as a man with the courage of his convictions, but willing to change his mind when presented with strong evidence.

Considered just as a work of science fiction, this story is very well-written, with interesting speculative content. It may not change anyone's opinions, but it's definitely worth reading.

Four stars.

The Alien Psyche, by Tom Purdom

Category: Psychology

Strolling over to the nonfiction, we find this article next to a large volume of Freud. The author wonders about the ways in which biological differences between human beings and the sentient inhabitants of other worlds may lead to differences in their minds. What kind of neuroses would be found among aliens that reproduce by fission, or are hermaphroditic?

The piece mostly deals with traditional Freudian analysis, although the author has to admit that there are many other schools of psychology, and that none of them are anywhere near an exact science. Maybe someday we'll know more about the workings of the mind, but for now this is all idle speculation.

Two stars.

Bond of Brothers, by Michael Kurland

Category: Spy Fiction

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Stuck between books by Ian Fleming and John le Carré is this tale of Cold War espionage. A fellow arrives at the secret headquarters of a US government agency, where his identical twin brother works. The brother is currently in a Soviet prison, after the Reds caught him spying. The only reason the protagonist knows about the headquarters, and his brother's location, is the fact that the twins have a telepathic link.

The hero manages to convince the head of the agency of this psychic connection, and volunteers to rescue his brother from the Commies. He goes undercover and faces many challenges in his quest to free his twin from their clutches.

Parachuting into the USSR.

The ESP gimmick isn't really relevant to the plot, which is a straightforward secret agent story. Some of Fleming's books, such as Thunderball and Moonraker, have more of a speculative feeling to them than this tale. I suppose it's an acceptable example of this sort of thing, but I felt a bit cheated by its appearance in a science fiction magazine.

Two stars.

Explosions in Space, by Ben Bova

Category: Astronomy

Passing by star charts and maps of the Moon, we arrive at the section of this tiny library dealing with the cosmos. We find an article dealing with things that go BOOM! in the heavens.

We begin with solar flares, and build up to entire exploding galaxies, with discussions of novae and supernovae along the way. The piece concludes with theories about the recently discovered, mysterious things known as quasars (quasi-stellar objects.) The author may not have the charm of Asimov, or the obscure knowledge of Ley, but he explains an interesting subject very clearly.

Four stars.

Dem of Redrock Seven, by John Sutherland

Category: Detective Stories

Leaning on some volumes of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett — we'll ignore the bestselling works of Mickey Spillane and stick with the classics — is this hardboiled yarn about a tough investigator and his sexy secretary, working on a case that could spell disaster for civilization.

Oh, did I mention the fact that these characters aren't human beings? In fact, they're the mutated descendants of insects, long after people contaminated Earth with radiation and nearly died off. The giant, intelligent insects now have their own sophisticated society, and the few remaining humans are living like savages in uncontaminated areas. They're only a minor nuisance, until the mysterious death of a government worker leads the hero to a hidden threat that could mean the end of the insects.

Clearly meant as a parody of private eye stories, this tongue-in-cheek tale is kind of silly — giving the secretary a lisp is particularly goofy and pointless — but amusing at times. I'll admit that the author does a good job writing from the insect point of view, and you may find yourself cheering for the hero over those dastardly humans. Like the first story in this issue, this one features the female lead coming to the rescue of the hero, which is a nice touch.

Three stars.

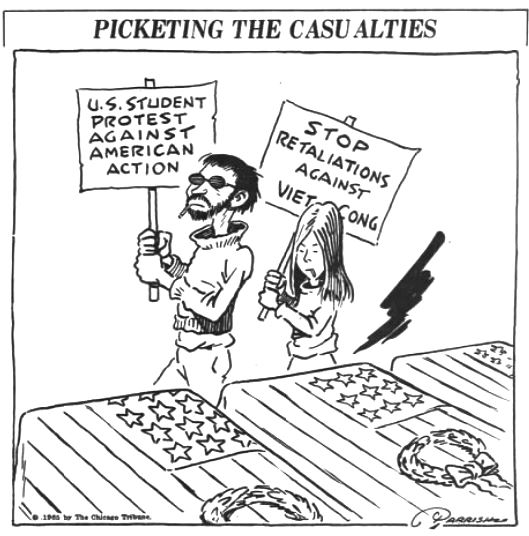

Bogeymen, by Dick Moore

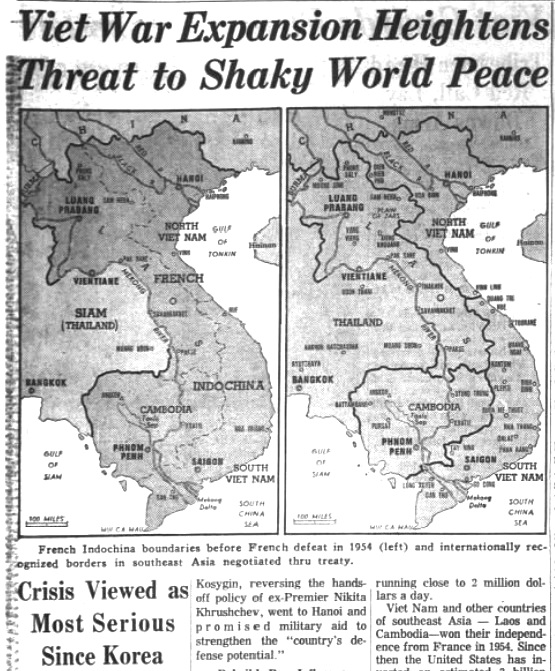

Category: War Stories

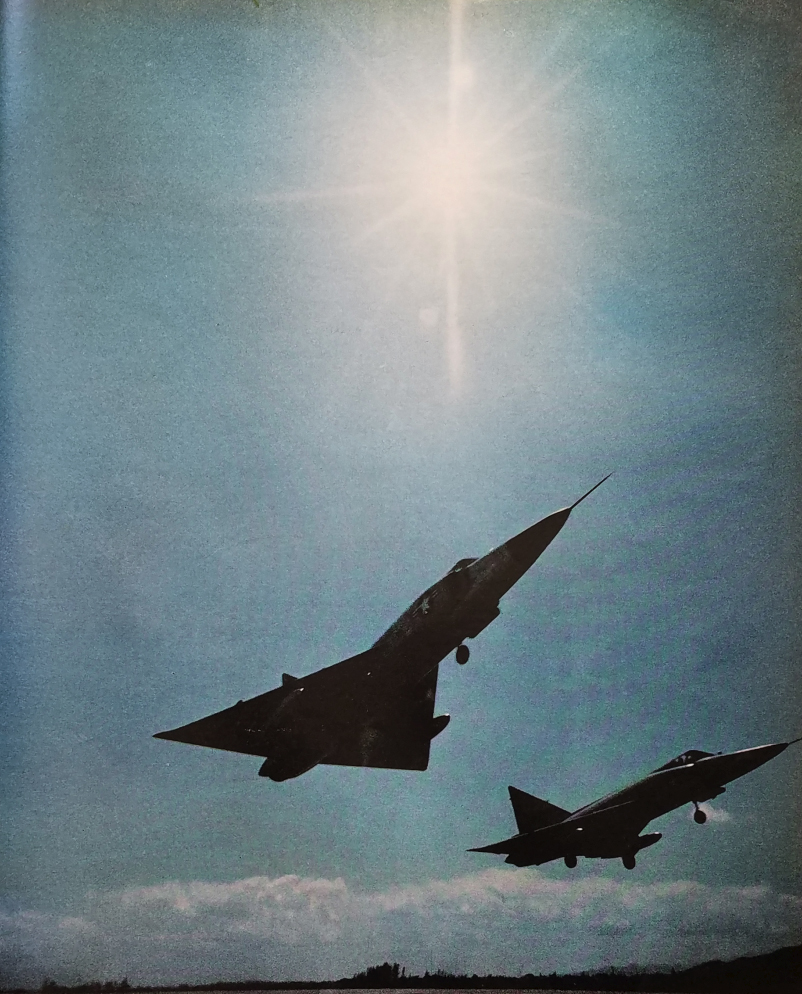

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

We'll head to the shelf that holds accounts of naval battles for this tale of combat with an enemy that remains unseen most of the time, like a submarine. Instead of sailing the seven seas, we're out in space, on a routine patrol of the inner solar system. The current situation between two vaguely defined rivals is hotter than a Cold War, although both sides refer to their violent encounters as accidents.

The patrol vessel, and that might be Mars at the top.

Word reaches the ship that a large force of enemy vessels is on its way to Mars from a base in the asteroid belt. Its target seems to be the friendly base on Phobos. Because it's extremely difficult to detect ships in the vastness of space, it's a matter of guesswork as to where the good guys should intercept the bad guys. It boils down to heading to the most likely place for them to appear and then waiting.

I have no idea what this is supposed to be.

Meanwhile, the crew alters its armed missiles, turning them into devices they can launch into space in order to increase the chances of detecting the enemy. The main character rather foolishly comes up with his own scheme for the armaments removed from the missiles, which lands him in very hot water indeed. He winds up having to go out in a one-person vessel in order to retrieve the arms, while risking own skin against the approaching enemy.

The hero in the small ship, I think, although this doesn't match the way I pictured it at all.

To be honest, I'm not sure if my brief synopsis is accurate at all. I found the technical aspects of the plot very hard to follow. The hero's actions are extremely unprofessional, putting the ship and crew in great danger just so he can play a hunch. The story also seemed quite long, as I slogged my way to the ending.

Two stars.

Have Your Library Card Ready

Is it worth a trip to the stacks? Maybe, maybe not. You've got one good story (although that judgement may be controversial) and one good article, along with other works ranging from poor to fair. I wouldn't go digging through musty old volumes to seek it out, but if it happens to be close, you might as well take a look. You might see something interesting.

She's only the librarian's daughter, but you really should check her out.

![[March 16, 1965] Browsing the Stacks (May 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n01_1965-05_0000-2-672x316.jpg)

![[March 12, 1965] Sic Transit (April 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/amz-0465-cover-672x372.png)

![[March 8, 1965] An Alien Perspective (April 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650308cover-435x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1965] Doctor Who And The B-Movie Rejects (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Web Planet)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650302menoptra-672x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1965] Tragedy and Triumph (March 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650228cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 22, 1965] Theory of Relativity (March 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Fantastic-v14-n03-1965-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

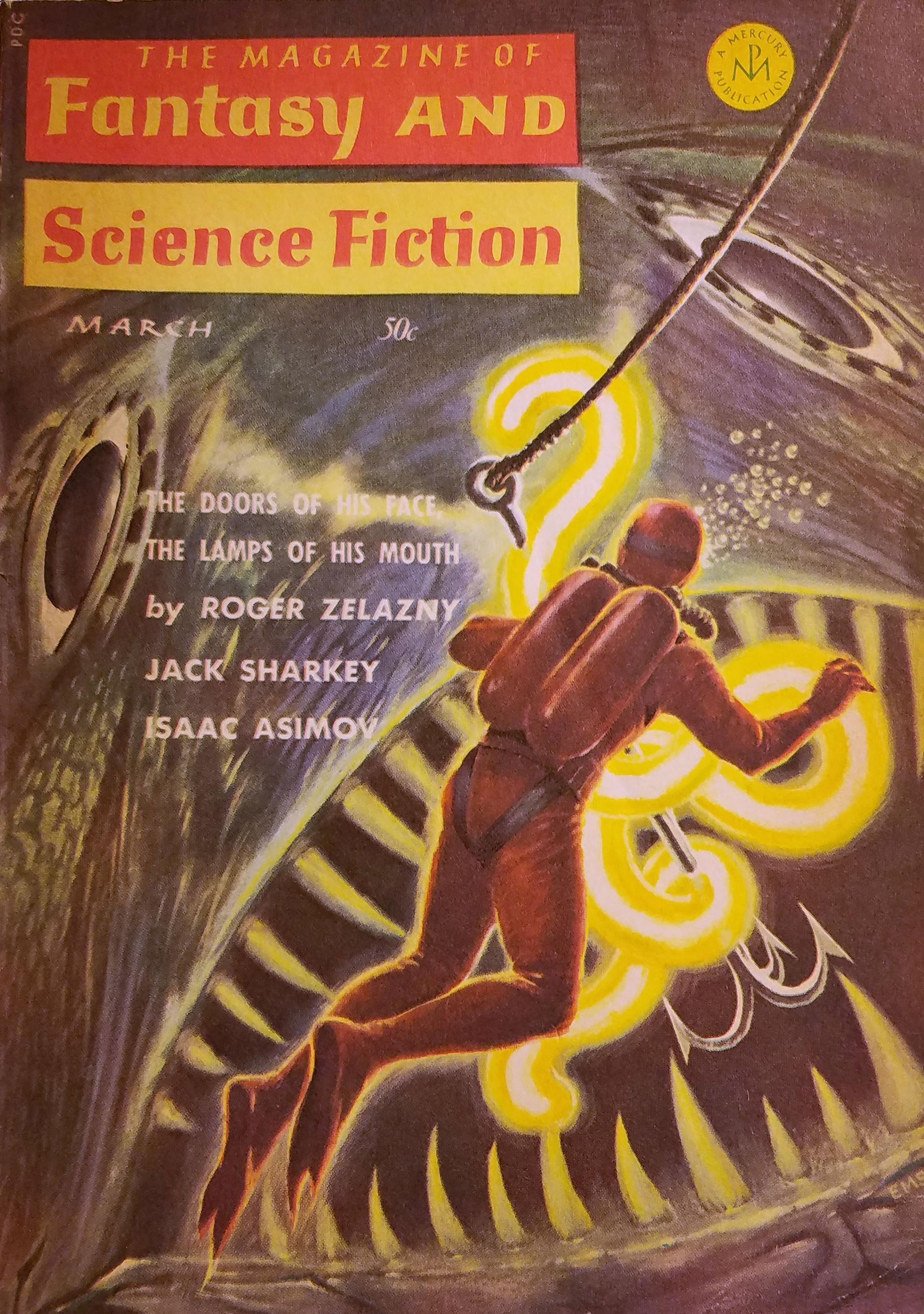

![[February 16, 1965] Return to a Quagmire (March 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650214cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1965] Mirabile Dictu, Sotto Voce (March 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/amz-0365-cover-524x372.png)

![[February 8, 1965] Roman Holiday (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Romans)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650208novaromainferno-672x372.jpg)

![[February 6, 1965] Too much of a… thing (March 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650204cover-672x372.jpg)